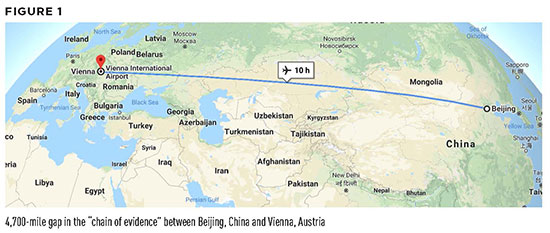

In United States v. Sinovel,1 a trade secret theft case against Sinovel, a Chinese wind turbine manufacturer, the prosecution faced a daunting problem: a 4,700-mile gap in the chain of evidence for two devices, a laptop and an external hard drive, containing crucial evidence. In short, the devices contained electronic evidence showing that Sinovel stole, adapted, and used wind turbine control software.2 A Chinese citizen found the laptop and external hard drive in a Beijing apartment. The Chinese citizen was reluctant to testify for the United States in a criminal trade case because he reasonably feared retribution in the People’s Republic of China. A second Chinese citizen – who was also unavailable to testify in the United States – transported the laptop and hard drive from Beijing to Vienna, Austria. (See Figure 1.)

The question was how to authenticate the devices without witnesses to explain the seizure and transport. The answer proved to be “whole device authentication.” Because computers are involved, this may sound complicated, but stick with me: This is the easiest legal concept you will learn this week, and it is broadly applicable to all litigators. While novel, “whole device authentication” only means that the proponent uses different categories of information3 (for example, pictures, emails, text messages) within a device (for example, a hard drive or cell phone) to authenticate the device and move it into evidence at trial.

Below, a practical example and an exercise show the simplicity of the idea. In addition to authenticating the device at trial, the information stored within the device tends to prove attribution: that a particular person possessed and used the device at a relevant time.

Concept is Easy; Application Can Be Difficult

An example and an exercise requiring zero forensic analysis demonstrate the simplicity of the idea. First, assume a police officer finds a cell phone in a park, and assume further that the information on the phone is accessible.4

Timothy M. O’Shea, U.W. 1991, is First Assistant United States Attorney, Western District of Wisconsin, Madison. O’Shea was the district’s Computer Hacking and Intellectual Property prosecutor from the inception of the program until 2018. O’Shea’s views do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Timothy M. O’Shea, U.W. 1991, is First Assistant United States Attorney, Western District of Wisconsin, Madison. O’Shea was the district’s Computer Hacking and Intellectual Property prosecutor from the inception of the program until 2018. O’Shea’s views do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Our example uses an Apple iPhone. Figure 2 is a screenshot of “tiles” or applications on an Apple iPhone. Behind nearly every “tile” is information that is idiosyncratic to the phone user. As a whole, the emails, reminders, calendar entries, photos, and the rest likely would identify the phone as one used by a particular person.

An exercise involving a real cell phone – the reader’s – drives the point home and demonstrates the simple, practical basis for whole device authentication. Assuming you carry a smartphone, the electronic communications on your phone (emails, text messages, and so on) are unique to you – messages to and from your colleagues, family members, and friends about things and events that matter to you. Likewise, the calendar entries show that the phone is yours – your dentist appointments, your court appearances, and birthdays and anniversaries that matter to you.

Further, even before accessing the metadata and geolocation information incorporated into the device’s image files, the photographs on the phone are of places you have been and are of your friends, relatives, pets, and so on. The phone internet browser’s “favorites” reflect your interests (news, sports teams, and so on) and practical aspects of your life (for example, your bank’s website). Similarly, the “map” and other easily accessible geolocation information on the phone – again, even before any forensics analysis – likely shows where you have been. When these different types of electronic information are combined, as they are on your phone, a judge or juror who learns a little bit about you would reasonably conclude that the phone is yours.

The idea applies equally to computers and internet-based accounts (such as Gmail and associated Google accounts). For computers, the information associated with frequently used computer “desktop” icons is similarly unique to the user and would likely convince a reasonable juror that the individual used the computer. The email application, for example, contains communications from an email address unique to the user, to and from people known to the user, and expressing information known to the user. “Contacts” lists phone numbers and email addresses of the user’s friends, relatives, and work associates, the “calendar” shows appointments and recurring events unique to the user, and the internet “favorites” and internet history likely reveal where the individual banks, shops, gets news, and engages in social media. Again, a reasonable juror, knowing a little about the user, viewing the information described above, would reasonably conclude the individual used the computer.

A skilled forensic examiner reviewing a person’s phone or computer will likely find many more digital artifacts proving relevant facts. The exercises above, however, go no farther than categories of information that you, the reader, can verify by browsing your own phone and computer. Still, at this point, two things should be clear: 1) Often, easily accessible electronic information demonstrates both authenticity and attribution; and 2) much of the information proving, in composite, who used the device containing electronic evidence is not otherwise relevant to the litigated point. For example, if a criminal defendant, in a 10-minute time span, uses his computer to check his bank account, exchange child pornography, and send an unrelated email, the internet history and email prove who committed the crime but are not otherwise relevant to the child pornography possession and distribution offenses.

If the same or related information is found on multiple devices or accounts, the information may demonstrate that a particular person used the devices and accounts. For example, assume a criminal defendant’s sister, Sue, hosted a party on July 10. On the defendant’s computer, one might find a July 10 Outlook “Party at Sue’s” calendar entry. The defendant’s Yahoo! email account might contain the electronic invitation and emails about what to bring to the party. The defendant’s phone might contain party photos that are automatically dated July 10 and contain geolocation data indicating that the pictures were taken in Sue’s backyard. Moreover, it is likely that duplicate calendar entries, emails, and images would be found on the phone and on the computer because of automatic synchronization or intentional downloading. For the same reason, it is likely that any emails found in the defendant’s Yahoo! account are also on his computer and phone. The information overlap tends to show that the criminal defendant controlled the devices and the locations or accounts where the information was found. An example from the Sinovel case drives the point home.

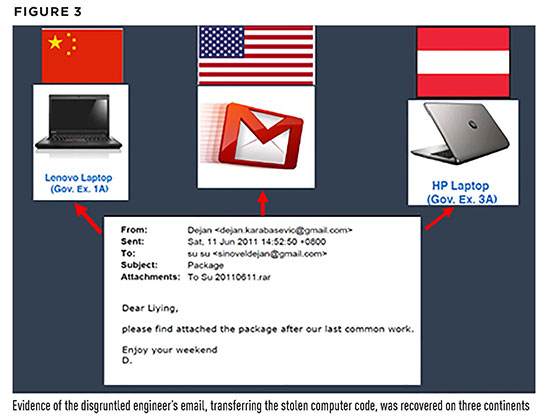

In Sinovel, the prosecution proved that on June 11, 2011, a disgruntled engineer who worked for AMSC, the victim company,5 sent a crucial email to a Sinovel engineer.6 As shown in the diagram in Figure 3, a .rar file was attached to the June 11 email. The .rar file contained the victim’s stolen trade secrets, worth, the district court found at sentencing, more than $550 million.7 The proof at trial showed that Sinovel used the stolen trade secrets – the software – in wind turbines in China and in the United States.

Evidence of the email was found on the disgruntled engineer’s Lenovo laptop (recovered in Beijing), on his Hewlett-Packard laptop (recovered in Austria), and within his Gmail account (obtained in the United States via a search warrant to Google). The overlap in electronic evidence helped show that the disgruntled engineer controlled the Gmail account and the Austrian and Chinese apartments and devices found at those locations.

Identity of Who Used and Possessed Devices is Relevant

In the Sinovel prosecution, the compelling trade-secret-theft evidence found on the devices recovered in Beijing and in Austria only mattered if the devices belonged to the disgruntled engineer. Whenever electronic evidence exists in criminal cases, attribution – who accessed, possessed, or controlled the device or internet-based account within which incriminating electronic evidence is found – almost always matters. After all, the government does not prove that crimes occurred in a vacuum but that particular persons (or entities) committed the crimes.

“Who” is essentially the first element of every crime. Jury instructions require the government to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that “the defendant” did a particular act – he or she possessed, distributed, traveled, transferred, defrauded, converted, and so on – and that he or she did so with a particular criminal intent.8 While rebutting an anticipated defense that someone else did it is often an issue in criminal cases,9 attribution, or proving who is at the computer keyboard (or on the phone, or accessing the online account), is nearly always at issue in cases involving electronic evidence.

Because “who” almost always matters, absent a confession or stipulation, otherwise innocuous emails, text messages, contacts, calendar entries, and so on are not only relevant but may be crucial to prove that a particular person used and possessed the device at a particular time. For example, a photograph of the disgruntled engineer’s daughter was the “desktop” background image on one of the engineer’s computers used to commit the trade secret theft. The desktop image was also found on a laptop recovered in Austria. An FBI analyst found the same image on the two devices recovered in Beijing.

Obviously, the daughter’s picture – and other images of the disgruntled engineer’s friends and relatives – did not prove the trade secret theft. However, the images proved that the engineer used the devices, and thus, in aggregate, established both the devices’ authenticity and who used the devices to commit the trade secret theft.10

Applicable Rules and Analysis

Three evidentiary rules guide the analysis. For each, I refer to both the federal evidence rule and the corresponding Wisconsin rule. First, Federal Rule of Evidence (Fed. R. Evid.) 104(a) (Wis. Stat. section 901.04(a)) permits the court to determine the admissibility of evidence before trial. Because whole device authentication may require significant forensic preparation, the prudent course is to raise this issue with the trial court well before trial. Under Fed. R. Evid. 104(a) (Wis. Stat. section 901.04(a)), the court is not bound by the evidentiary rules – with the exception of those relating to privilege – in preliminary determinations of admissibility.11

Second, under Fed. R. Evid. 901(a) (Wis. Stat. section 909.01), a proponent must produce sufficient evidence to support a finding that the item is what the proponent claims it to be. “Only a prima facie showing of genuineness is required; the task of deciding the evidence’s true authenticity and probative value is left to the jury.”12 A proponent “is not required to rule out all possibilities inconsistent with authenticity, or to prove beyond any doubt that the evidence is what it purports to be.”13

Third, Fed. R. Evid. 901(b) (Wis. Stat. section 909.015) provides a nonexhaustive authentication example list. For example, an item may be authenticated based on its “appearance, contents, substance, internal patterns, and other distinctive characteristics of the item, taken together with all the circumstances.”14 Litigants regularly use this rule to ask for admission, as evidence, of guns, hard drives, and other items bearing serial numbers.

Similarly, electronic evidence often contains distinctive characteristics, some of which are readily observable, such as a nickname used in an email, and others, that require the use of forensic tools, such as a hash algorithm, to understand or interpret. A second rule is implicated when part of the proponent’s authentication argument relies on “overlap” evidence – for example, when identical pictures or communications are found on numerous devices or accounts.15 In such cases, proponents may use Fed. R. Evid. 901(b)(3) (Wis. Stat. section 909.015(3)) to authenticate an item, such as a computer containing numerous emails, through comparison with identical emails found within an independently authenticated account, such as a Gmail or Yahoo! account.Collectively, the distinctive characteristics within electronic evidence make Fed. R. Evid. 901(b)(4) (Wis. Stat. section 909.015(4)) “one of the most frequently used [rules] to authenticate e-mail and other electronic records.”16

When these different types of electronic information are combined, as they are on your phone, a judge or juror who learns a little bit about you would reasonably conclude that the phone is yours.

Several cases involving information that was authenticated based on internal characteristics rather than on the “chain” of evidence guide the analysis. In United States v. Fluker,17 the Seventh Circuit found that electronic evidence – a set of emails – was properly authenticated under Fed. R. Evid. 901(b)(4) when the distinctive characteristics and circumstances sufficed to show that the emails were genuine. In Fluker, the email address indicated that the email was sent by a member of “MTE,” a business organization used by conspirators, and the email contents demonstrated that the sender possessed information that only a scheme “insider” would know.18

Likewise, in United States v. Harvey,19 anonymous notebooks found near a remote marijuana grow operation were admitted under Fed. R. Evid. 901(b)(4) when information within the notebooks – references to Harvey’s dog – and other circumstantial evidence tied Harvey to the remote location.

In United States v. Dumeisi,20 a Chicago-area man was convicted of acting as an unregistered agent of Saddam Hussein’s government based in part on documents found in a foreign country. At trial, the government introduced the “Baghdad file,” a collection of Iraq Intelligence Service (IIS) documents recovered after the fall of Baghdad in 2003.21 Dumeisi challenged the provenance of the Baghdad file.22 The Seventh Circuit found that the circumstances and the content – certain codes, symbols, and abbreviations idiosyncratic to the IIS – sufficed to authenticate the file under Fed. R. Evid. 901(b)(4).23

In Dumeisi, the Seventh Circuit compared the authentication of the Baghdad file to letters introduced in United States v. Elkins.24 Elkins involved a man charged with scheming to sell restricted aircraft to Libya, a prohibited country.25 In Elkins, the Eleventh Circuit held that several letters found in the former West Germany in a briefcase allegedly owned by another scheme participant were properly authenticated in light of the contents, the apparent authorship, and other circumstances.26

In United States v. Vidacak,27 as in Elkins and Dumeisi, the court applied Fed. R. Evid. 901(b)(4) to evidence found outside the United States. Vidacak was accused of lying to immigration authorities regarding his military service in the Bosnian civil war.28 Military personnel records recovered from the Zvornik Brigade headquarters, showing that Vidacak was a member of the Army of the Republika Srpska, were part of the government’s proof.29 Although the person who recovered the records in the former Yugoslavia could not explain the pre-seizure history of the information, the Fourth Circuit approved the admissibility of the records, in part based on the internal patterns and distinctive characteristics of the military records.30

Dumeisi, Elkins, and Vidacak show that Fed. R. Evid. 901(b)(4) may be used to authenticate evidence regardless of “chain of custody” and based solely on distinctive characteristics. Moreover, the nature of electronic evidence provides a unique ability to understand that an item is what the proponent claims it to be. In Lorraine v. Markel American Insurance Co., then-U.S. Magistrate Judge Paul W. Grimm – now a U.S. District Court Judge for the District of Maryland – wrote a comprehensive analysis of the admissibility of electronic evidence.31 The Lorraine opinion strongly emphasized the importance of Fed. R. Evid. 901(b)(4) for the authentication of email and other electronic records.32

Time has proven Judge Grimm correct.33 Some distinctive characteristics that may be present within electronic evidence do not require special forensic tools or techniques to discern (for example, use of certain email addresses, content expressing information that only certain people know, use of code or nicknames, file “properties” including time and date stamps, and known events that corroborate electronic information). Other distinctive characteristics are discerned using forensic tools (for example, complex metadata analysis and the application of hash tools to a file or to an entire hard drive).

Two cases explore the volume and comprehensive nature of electronic evidence: Riley v. California34 and United States v. Ganias.35 Although neither case involves the admissibility of electronic evidence, both explain how electronic evidence provides unusual insight into who used the device and when, where, and how the device was used. When the distinctive characteristics of information found in a device answer the who, what, when, where, and how about a device, sufficient evidence exists for a finding that the device is what its proponent claims it to be.

Whenever electronic evidence exists in criminal cases, attribution – who accessed, possessed, or controlled the device or internet-based account within which incriminating electronic evidence is found – almost always matters.

In Riley, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected searches of cell phones incident to arrest and made clear that search warrants are required for cell phones found on an arrestee.36 In doing so, the Riley opinion explored how the characteristics of “smart” phones provide extraordinary insight into a person’s life in light of the volume and types of information stored in a cell phone.37 The Court observed that a cell phone may contain bank information, addresses, calendars, contact lists, still and video depictions, notes, detailed communication records, internet search and browsing histories, geolocation information, and software application downloads and use histories.38

Further, the Court observed, cell phone information allows a forensic examiner to “reconstruct” an individual’s life through “a thousand photographs labeled with dates, locations, and descriptions.”39 That information, when placed in the chronological and geographic context of other information within the device, “reveal[s] much more in combination than any isolated record.”40 The Court opined that digital data, such as internet searches and browsing history, is often unique in its ability to “reveal an individual’s private interests or concerns.”41

In Ganias, the Second Circuit, sitting en banc, overruled an earlier panel decision holding that law enforcement officers lacked good faith in executing a 2006 search warrant against computer evidence first secured in a different investigation in 2003.42 The panel had held that investigators in the original case should have segregated and extracted only the pertinent information relating to the first target; it was error to retain additional information.43 Consequently, the panel ordered the evidence from the 2006 search suppressed.44

In overruling the original decision, the en banc Second Circuit largely rejected the central analogy used in the panel decision – that computer records are like documents stored in a filing cabinet.45 In contrast, the en banc opinion noted that a single computer file may be stored in a fragmented way, and with unseen redundancies, on the storage medium.46 The Second Circuit noted that a “digital storage device … is a coherent and complex forensic object”47 and the “complexity of the data thereon” may influence subsequent authentication of the device at trial.48

In addressing privacy concerns in Ganias, the en banc Second Circuit cited Riley v. California49 while observing that information stored on an electronic device might provide unusual insight into the user’s identity, actions, thoughts, and location.50 The en banc Second Circuit also cited United States v. Galpin, in which the Second Circuit previously noted that “advances in technology and the centrality of computers in the lives of average people have rendered the computer hard drive akin to a residence in terms of the scope and quantity of private information it may contain.”51

Riley and Ganias dealt with Fourth Amendment privacy interests in electronically stored information. While the scope of information on an electronic device can raise privacy concerns, a real-world analogy provides perspective: In drug and firearm possession cases, trial courts regularly allow litigants to introduce evidence that is indicia of occupancy or control to show who lived where contraband was found (for example, a driver’s license, photographs, prescription medication, or correspondence).52

Applying the same idea to electronically stored information, the content, volume, variety, and complexity of electronically stored information can show the who, what, when, where, and how of computer or phone use in connection with a crime. For authenticity purposes, information found within an electronic device – files, pictures, emails, and other electronic communications unique to the user, each file with its own electronically idiosyncratic metadata – shows that the device is what the government says it is, a device used at a time relevant to the offense by the defendant.

Fourth Amendment Implications

Although this article primarily focuses on the admissibility of electronic evidence and the devices in which that evidence is found, for criminal cases the Fourth Amendment considerations deserve particular attention. Two important interests are in genuine tension.

On one hand, as noted above, because the identity of the person who used and possessed the device containing incriminating evidence almost always matters, otherwise innocuous emails, text messages, contacts, calendar entries, and so on may be crucial to authenticate the device and prove attribution. On the other hand, important Fourth Amendment privacy interests are at stake, and thus law enforcement searches must be reasonable, including – as is discussed next – searches conducted pursuant to warrants. While it is wholly appropriate to search for information showing access and control,53 prosecutors, agents, and analysts must properly guard against exploratory, unfettered rummaging through electronic evidence.54

Digital data, such as internet searches and browsing history, is often unique in its ability to “reveal an individual’s private interests or concerns.”

A timing problem also exists. While authenticity is determined at or close to trial and attribution is proved in the context of trial, identifying idiosyncratic images, communications, and other forensic artifacts requires considerable time and effort for the prosecution. This is especially true when the information is spread across multiple devices or accounts. When authenticity is contested, the prosecution team needs time to identify and prepare exhibits derived from the electronic evidence to establish authenticity.

A solution that safeguards a defendant’s privacy interests is to provide to the judge reviewing the search warrant affidavit a careful explanation of how different types of information on the subject device, or within the online account, can establish who used or controlled the device or account.55 Such “user attribution” evidence is analogous to the search for “indicia of occupancy” evidence in a residence.56 As noted above, the same information can be crucial to authenticate the devices. A thoughtful explanation in the search warrant affidavit, coupled with judicial consent in the form of the search warrant, will go a long way toward showing that the search is reasonable.

Conclusion

Different categories of electronic information found within devices or online accounts can be crucial to authenticate the device or account and establish attribution. In combination, these categories show whole device authentication, that is, a prima facie case that the item is what the proponent says it is under Fed. R. Evid. 901(a) or its Wisconsin counterpart, Wis. Stat. section 909.01. When personalized, unique information is spread across multiple devices or online accounts, that information tends to prove that the person controlled the accounts, the devices, and the locations where the devices are found.

Endnotes

1 No. 13-cr-84-jdp (W.D. Wis. 2013).

2 The software was developed in Wisconsin and was stored on – and stolen from – a server in Middleton.

3 When talking to the jury, use the word “information” instead of “data” to describe electronic evidence. The term “information” is both accurate and more accessible to the jury.

4 This nonforensic exercise only illustrates the simplicity of the concept of whole device authentication and does not suggest that lawyers should poke around into live phones or computers containing electronic evidence. That is a bad idea, for many reasons not explored here. While I cannot overstate the importance of working closely with forensic analysts, this article does not address computers or cell phones forensics. For an introduction to computer and cell phone forensics, see Ovie Carroll, Challenges in Modern Digital Investigative Analysis, 65 U.S. Att’y Bull., Jan. 2017, at 25-38; Daniel Ogden, Mobile Device Forensics: Beyond Call Logs and Text Messages, 65 U.S. Att’y Bull., Jan. 2017, at 11-14.

5 Indictment, United States v. Sinovel, No. 13-cr-84-jdp (W.D. Wis. June 27, 2013), ECF No. 25.

6 Government’s Exhibit No. 3K74, United States v. Sinovel, No. 13‑cr‑84‑jdp (W.D. Wis. 2013).

7 United States v. Sinovel, No. 13-cr-84-jdp (W.D. Wis. July 10, 2018), ECF No. 501, p. 108.

8 See, e.g., Wis. Criminal Jury Instructions (2018); Pattern Criminal Jury Instructions of the Seventh Circuit (2012 ed.).

9 See Fed. R. Crim. P. 12.1 (requiring alibi notice).

10 Opinion & Order at 11, United States v. Sinovel, No. 13-CR-84-jdp (W.D. Wis. Nov. 15, 2017), ECF No. 350.

11 See Hon. Paul W. Grimm, Gregory P. Joseph & Daniel J. Capra, Best Practices for Authenticating Digital Evidence 2 (2016).

12 United States v. Fluker, 698 F.3d 988, 999 (7th Cir. 2012) (citing United States v. Harvey, 117 F.3d 1044, 1049 (7th Cir. 1997)); see also State v. Deadwiller, 2012 WI App 89, ¶ 13, 343 Wis. 2d 703, 820 N.W.2d 149 (to authenticate an item, “all that need be shown is that it is improbable that the original item has been exchanged, contaminated or tampered with” (further citation and internal quotations omitted); Grimm et al., supra note 9, at 2-3 (describing the roles of the trial court and jury).

13 Achey v. BMO Harris Bank N.A., 64 F. Supp. 3d 1170, 1175 (N.D. Ill. 2014) (quoting Boim v. Quranic Literacy Inst., 340 F. Supp. 2d 885, 915 (N.D. Ill. 2004)).

14 Fed. R. Evid. 901(b)(4); Wis. Stat. § 909.015(4).

15 See Fed. R. Evid. 901(b)(3).

16 Lorraine v. Markel Am. Ins. Co., 241 F.R.D. 534, 546 (D. Md. 2007); see also Grimm et al., supra note 9, at 8.

17 698 F.3d 988, 998-1000 (7th Cir. 2012).

18 Id.; see also Grimm et al., supra note 9, at 9.

19 117 F.3d 1044, 1049 (7th Cir. 1997).

20 424 F.3d 566, 571-72 (7th Cir. 2005).

21 Id.

22 Id. at 574-75.

23 Id. at 575.

24 Id. at 575-76.

25 United States v. Elkins, 885 F.2d 775, 779 (11th Cir. 1989).

26 Id. at 785.

27 553 F.3d 344 (4th Cir. 2009).

28 Id. at 347.

29 Id.

30 Id. at 350-51.

31 Lorraine, 241 F.R.D. at 538-85; see also Grimm et al., supra note 11 (revisiting and expanding upon the authentication issues first explored by Judge Grimm in Lorraine).

32 Lorraine, 241 F.R.D. at 546-48.

33 See State v. Brownlee, No. 2015AP2319-CR, 2017 WL 5624784 (Wis. Ct. App. Nov. 21, 2017) (unpublished) (review denied) (text messages on cell phone were authenticated based on other information on the cell phone – namely the defendant’s photograph and email address – showing that the defendant used the cell phone); State v. Giacomantonio, 2016 WI App 62, ¶¶ 20-25, 371 Wis. 2d 452, 885 N.W.2d 394 (text messages on victim’s phone were authenticated based on circumstantial evidence including defendant’s cell phone number as the text message sender and where message content expressed information consistent with the defendant’s living arrangements); United States v. Lewisbey, 843 F.3d 653, 658 (7th Cir. 2016) (authenticating two cell phones based on where the phones were found and because the electronic information on the phones related to the crime, identified the user and his associates, and included contact information for the user’s former employer); see also United States v. Reed, 780 F.3d 260, 266-69 (4th Cir. 2015) (authenticating cellphone based on photos and text messages found within device); United States v. Brinson, 772 F.3d 1314, 1320-21 (10th Cir. 2014) (authenticating Facebook messages when account was linked to known email address and defendant used own name in postings); United State v. Bertram, 259 F. Supp. 3d 638, 640-41 (E.D. Ky. 2017) (authenticating emails based on email addresses and content unique to defendants and co-conspirators); United States v. Browne, 834 F.3d 403, 408-16 (3d Cir. 2016) (allowing authentication of Facebook chat records based on circumstantial evidence, including existence of biographical details of defendant in chat records); United States v. Benford, No. CR-14-321-D, 2015 WL 631089, at *5-6 (W.D. Okla. Feb. 12, 2015) (authenticating text messages because they related information uniquely tied to the defendant).

34 134 S. Ct. 2473 (2014).

35 824 F.3d 199 (2d Cir. 2016) (en banc).

36 Riley, 134 S. Ct. at 2485.

37 Id. at 2489.

38 Id. at 2489-90.

39 Id. at 2489.

40 Id.

41 Id. at 2490.

42 824 F.3d 199, 205-06 (2d Cir. 2016).

43 United States v. Ganias, 755 F.3d 125, 138-40 (2d Cir. 2014).

44 Id. at 142.

45 Ganias, 824 F.3d at 211-12.

46 Id. at 212-13.

47 Id. at 213.

48 Id. at 215.

49 Riley, 134 S. Ct. at 2489-90.

50 Ganias, 824 F.3d at 231.

51 Id. (referencing and quoting United States v. Galpin, 720 F.3d 436, 446 (2d Cir. 2013)).

52 See, e.g., United States v. Pulido-Jacobo, 377 F.3d 1124, 1132 (10th Cir. 2004) (finding receipt to be admissible nonhearsay because “the government offered the engine receipts only to show that [defendant] had sufficient control of the car to store an old receipt in it”).

53 See Messerschmidt v. Millender, 565 U.S. 535, 552-53 (2012) (finding that officers were justified in searching family’s home for evidence of former foster son’s gang affiliation, because personal property could evidence son’s use and control of the premises and his connection to evidence found within the home).

54 Several recent cases explore the scope of search warrants in the context of devices and online accounts. See State v. Rindfleisch, 2014 WI App 121, ¶¶ 32-41, 359 Wis. 2d 147, 857 N.W.2d 456 (upholding warranted searches of online email accounts against a challenge to scope); United States v. Blake, 868 F.3d 960, 973-74 (11th Cir. 2017) (criticizing several Facebook search warrants as “general warrants” permitting exploratory rummaging, but ultimately upholding the searches based on good faith); United States v. Wey, 256 F. Supp. 3d 355, 379-87 (S.D.N.Y. 2017) (concluding that search warrants, as they related to electronic devices, were insufficiently particular to provide guidance to searching forensic agents regarding parameters of search); United States v. Westley, No. 3:17-CR-171 (MPS), 2018 WL 3448161 (D. Conn. July 17, 2018) (finding that series of Facebook search warrants were sufficiently particular and were not overbroad when warrants sought information relating to crimes under investigation, identified individual users, and tended to show gang members’ association with each other).

55 United States v. Ulbricht, 858 F.3d 71, 99-105 (2d Cir. 2017), provides an excellent example. In Ulbricht, the warrants, for computers and email accounts, authorized the search for evidence that could show that Ulbricht committed a series of crimes while posing as the “Dread Pirate Roberts (DPR)” who ran the Silk Road website. The warrants authorized a search for information directly relating to the crimes under investigation and for information showing that the computer user had political or economic views associated with DPR and that the user showed “linguistic patterns or idiosyncrasies” associated with DPR’s communications. While this permitted a broad search, the Second Circuit upheld the warrants because proving that Ulbricht was DPR was crucial to proving the case.

56 Cf. United States v. Pulido-Jacobo, 377 F.3d 1124, 1132 (10th Cir. 2004).