To say that communication is an important aspect of the law is probably an understatement. Communication forms the bedrock of various constitutional rights,1 common-law standards,2 statutory provisions,3 and professional guidelines,4 and most lawyers likely spend the majority of their professional time communicating with clients or coworkers through written or spoken language.

But as mundane a phenomenon as communication might seem, advances in neuroscientific knowledge have found that it is one of the human brain’s most complicated and complex abilities. As a result of this knowledge, collective understanding of how humans communicate has never been better developed. These empirical findings present a real opportunity for the law to reflect on its own systems and processes. The more lawyers know about what it means to communicate, the better we can appreciate the implications of our communicative actions within the law’s overarching legal frameworks, and the better we can appreciate how the law and human communication intersect.

To illustrate some of these implications and intersections, this article briefly discusses the mental and cognitive mechanisms that underlie communication and what those mechanisms might mean for legal professionals. In doing so, the discussion identifies particular risk factors that legal professionals should be aware of during their interactions with clients or parties and enumerates best practices that legal professionals can adopt to ameliorate potential risks. This interdisciplinary perspective on communication should add some pragmatic tools to lawyers’ professional toolkits and provide insight into the sorts of human behaviors that ultimately make the legal profession possible.

Defining Cognitive Communication

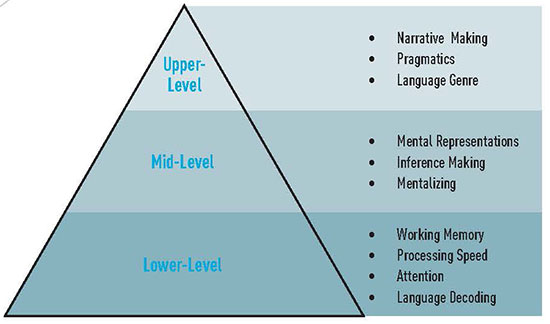

Neuroscience uses the term cognitive communication to refer to the mental and cognitive mechanisms that underlie communication. The term encompasses an array of functions that support both the productive aspects of communication (for example, speaking and writing) and the receptive aspects of communication (for example, listening and reading). Although in reality these brain functions exist as complex patterns of neural activity within complex networks of neural cells, this article conceptualizes them as a hierarchy of cognitive processes and abilities that together make up cognitive communication. (See Figure 1.) For the purposes of this discussion, therefore, cognitive communication is an umbrella term for all the interconnected cognitive functions that let humans communicate.5

Joseph A. Wszalek, U.W. 2015 cum laude, Order of the Coif, is the director of scientific writing and scholarship at the U.W.-Madison School of Nursing. He was the inaugural member of the U.W.’s JD/PhD dual-degree program in neuroscience and the law, through which he earned his law degree and a doctorate in neuroscience. His academic research explores the intersection between cognition, the brain, and the law, with an emphasis on language and communication.

Joseph A. Wszalek, U.W. 2015 cum laude, Order of the Coif, is the director of scientific writing and scholarship at the U.W.-Madison School of Nursing. He was the inaugural member of the U.W.’s JD/PhD dual-degree program in neuroscience and the law, through which he earned his law degree and a doctorate in neuroscience. His academic research explores the intersection between cognition, the brain, and the law, with an emphasis on language and communication.

“Lower-level” Cognitive Functions. At the base of the pyramid are the cognitive functions that relate to the brain’s ability to hold, access, and move information whenever a person performs a mental task.6 Think of these lower-level functions as the brain’s raw computing resources: They are the RAM or SSD that lets the brain “run.” Key examples of these lower-level functions are working memory (that is, “short-term memory,” the brain’s ability to temporarily hold and move information), processing speed (the rate at which a brain is able to move and access information), and language decoding (the brain’s ability to extract meaning from letters or sounds).

These functions are mostly automatic and subconscious: Unless a person has an injury or a disability, his or her working memories or language-decoding skills generally work without having to “think” about it. These functions are also the ones most typically associated with cognitive deficits; learning disabilities and cognitive disorders typically affect the memory and processing resources necessary for language and communication.

“Mid-level” Cognitive Functions. In the middle are the cognitive functions that relate to the brain’s ability to create mental representations of language and communication. Mental representations are the patterns of information that a brain forms as a person experiences communication; effectively, they are the “movies” or “pictures” that you experience in your mind’s eye as you read, listen, or think.

Being able to make these mental representations is a vital part of communication, so the mid-level functions are particularly important.

Because humans have not figured out how to have psychic powers, I cannot transmit my conscious mind directly into yours. Instead, I have to use language and communication to express the ideas (that is, mental representations) in my mind so that your brain can try to reverse-engineer those ideas based on the instructions that my communication supplies. In this regard, the mid-level cognitive functions are like a suite of software programs: They take the raw information from and about language and communication and turn it into a usable mental product.

An example demonstrates how mental representations are formed. Consider the following sentence: Tomorrow Jack will argue a case before the Wisconsin Supreme Court. By writing this sentence, I’m asking readers’ brains to recreate the scenario that these words describe. For many readers, this should be easy: They’ve been in the Wisconsin Supreme Court Hearing Room, and they’ve argued cases before judges, so they should be able to “see” the scenario of a person arguing before the court.

Even though this is a simple sentence, the brain has to perform some complicated cognitive tricks to complete the mental representation. First, it has to make inferences to fill in missing information. For example, your brain probably assumes that Jack is a lawyer. It knows that lawyers argue cases before courts and nonlawyers do not, so it uses inferencing to connect the dots between “Jack” and “lawyer.” Similarly, your brain probably assumes that Jack is a man: It knows Jack is a usually a male name, so it infers that Jack is a man.

Second, the brain uses a cognitive function called mentalizing. Mentalizing lets the brain attribute mental states such as feelings and goals to the people within the mental representation. In this case, your brain probably assumes that Jack wants to win his case, and that he is confident or nervous or both. Your brain knows what these goals and emotions feel like, and it knows that these particular mental states are associated with arguing cases in court, so it recreates them to help itself better represent the sentence. Once your brain has done all that, you “understand” the sentence by having a recognizable mental movie of the context the sentence describes.

Any individual or contextual factors that make it more difficult for a person to use or access cognitive-communication resources risk making that person’s communication slower or poorer or both.

As communication misunderstandings or misinterpretations might suggest, however, creating mental representations is by no means an all-or-nothing undertaking. The more information a brain has, the more detailed the representations it creates can be. For example, readers who have been in the Wisconsin Supreme Court Hearing Room know what the room looks like, how big it is, and what its spatial orientation is. They know this because their brain received sensory information from visual, auditory, and other senses as they were physically in the Hearing Room. When these readers’ brains read the words before the Wisconsin Supreme Court, they can “replay” that sensory information to create a representation that is grounded in the perceptions they experienced; effectively, the brain can put itself (and the reader) back in the Wisconsin Supreme Court Hearing Room as it makes mental representations.

But when the brain does not have first-hand sensory information, it must improvise. Consider this sentence: Tomorrow Jack will take the train from Florence to Prato. Now the reader’s brain probably has less information to work with. You probably haven’t taken a train from Florence to Prato, so your brain cannot recreate a representation that is grounded in your own direct sensory experiences. You can still infer that Jack is a man, but now it is less clear from the text why he is taking the train, so your brain’s inferences about Jack’s identity and mental states are not as clear. As a result of this ambiguity, your mental representation is less detailed and more abstracted because your brain had to use whatever general information about trains and people riding them, or whatever experience riding other trains, you might have.

This mental representation is less a movie and more a storyboard: Your brain can create skeleton representations of a person taking a train, but it does not have the information it needs to fully flesh them out.

Now consider this third sentence: Tomorrow Jack will take the thing and move it to the side of the other thing. For this sentence, the reader’s brain has almost nothing to work with. The words and concepts are all completely abstracted, so the brain cannot ground them in any perceptions or sensations, and it cannot use them to make inferences about what Jack is doing. The mental representation a reader gets for this sentence is probably not much of a picture or a movie at all. Not until concrete information is added (for example, Tomorrow is recycling-collection day) can the brain say, “Oh, now I see what’s going on” and provide a better-developed representation of the sentence’s scenario (for example, a man taking his recycling bin to the side of the street).

Because mental representations can vary wildly depending on the information in the language sample and the information available within the reader’s or listener’s head, the quality of mental representation output is a spectrum that can change from person to person and from communication to communication.

Legalese is notoriously inaccessible, but even relatively simple legal language uses unique or uncommon words and describes uncommon social situations.

“Upper-level” Cognitive Functions. At the top of the cognitive-communication pyramid are cognitive functions that relate to the brain’s ability to use communication for a particular purpose.7 Narrative making, or the ability to craft coherent stories, is a cognitive skill with which a person controls the content, structure, and logic of his or her communication. Similarly, pragmatics is the skill though which a person adjusts communication to account for social context or purpose; for example, a lawyer likely uses more formal communication when speaking to a sitting judge and less formal language when speaking to a long-term client.

Finally, language genre refers to the ability to produce or receive communication across a variety of categories like expository communication (for example, describing postconviction rights to a defendant) or procedural communication (for example, instructing a client how to apply for unemployment benefits).

Put succinctly, the upper-level cognitive functions help people translate internal mental representations into external communication messages. To continue the computer analogy, the upper-level functions are the user interface that moderates how you and other people interact with your brain’s internal processing.

In contrast to the other two levels, the upper-level cognitive functions are often apparent as people communicate with each other. Someone without good narrative-making function might tell stories that are disjointed or repetitive, and someone without good pragmatics might use word choices or grammar constructions that are socially inappropriate. And in contrast to the lower-level functions, which are mostly subconscious and automatic, the upper-level ones are generally conscious and effortful: Producing a narrative and using contextually appropriate language reflect choices and adjustments a person constantly makes throughout communication.

In summary, cognitive communication refers to the aggregate mental and cognitive resources that allow human beings to communicate with one another. These cognitive functions are complex, interconnected phenomena that rely on functional and anatomical connections that span the human brain. As a result, cognitive communication is not a binary, all-or-nothing skill. The unique make-up of knowledge, experience, and anatomy will determine any given individual’s cognitive-communication resources, and the particular context will influence how well or how quickly that individual can access those resources.

Figure 1

Cognitive Functions that Underlay Cognitive Communication

What Cognitive Communication Means

Because cognitive communication is less a question of whether a person has a particular cognitive talent and more a question of how a person’s ability to access cognitive resources plays out in a given context, any factor (internal or external) that can in any way slow or frustrate the lower-level, mid-level, and upper-level cognitive functions can slow or frustrate communication. This point is important enough to bear reiterating: Any individual or contextual factors that make it more difficult for a person to use or access cognitive-communication resources risk making that person’s communication slower or poorer or both.

You will probably never have a client or party who has absolutely no cognitive-communication ability, and you will probably never be in a context where communication is absolutely impossible; you will and do, however, work with clients who have individual cognitive-communication risk factors or in situations where such risk factors exist. Being aware of what some of these risk factors are and how they might impede or challenge cognitive communication will help lawyers be more mindful and more effective legal actors as they communicate with others.

Context-based Risk Factors. It should come as no surprise that legal contexts can be difficult settings in which to communicate. Although some contexts will always be more challenging than others, several contextual factors are almost guaranteed to apply to any legal setting. Recognizing these factors and how they might affect legal work is a valuable first step in translating knowledge about cognitive communication into meaningful outcomes.

• Challenging language.8 Legalese is notoriously inaccessible, but even relatively simple legal language uses unique or uncommon words and describes uncommon social situations.

This likely puts pressure on the lower-level and mid-level stages of cognitive communication. Uncommon words (for example, “naturalization”) and long, complex sentences (for example, those contained in Padilla warnings) are harder to read and harder to parse, which means that they require more of the lower-level memory and decoding resources than simpler language. This in turns means that the reading or listening will be slower or poorer or both, depending on the person’s available cognitive resources.

Similarly, uncommon, abstract legal language translates into slower or poorer internal representations. Assuming I can physically parse a Padilla warning, for example, I might not have the experiences or knowledge necessary to form sufficient mental representations of concepts like “deportation” and “naturalization.” My brain will likely rely on inferences from whatever background information is most relevant, regardless of how “accurate” that information is (an episode of Law & Order, for example). As a result, I might form mental representations that are abstract and bare-bones, as was the case in the example sentence with the train. How accurate this resulting mental representation is will influence how accurate my comprehension is, which will in turn influence how well I can manipulate the comprehension to plan actions and make decisions.

Learn More

Learn more about effective communication at the Wisconsin Solo & Small Firm Conference, Oct. 24-26 in Wisconsin Dells. Friday sessions include:

- Motivating Communication: How to Get People to Talk More About What Matters Most

- How to Speak so People Stay Awake and Do Not Hate You

www.wisbar.org/wssfc

• Communication disparity between the legal professional and the layperson.9 Because of their training and experience, legal professionals have communication benefits that laypersons might not. Legal professionals have more exposure to tangible perceptions of complex ideas (for example, a court, a trial, or a case), so we can internally “see” those ideas more quickly and more accurately than people without such exposure can. This means that not only might laypeople be objectively slower and worse at communicating in legal contexts when compared to nonlegal contexts, they might be relatively slower and worse when compared to the legal professional.

This disparity could further slow or challenge the layperson’s lower-level and mid-level cognitive functions if the communication between professional and layperson reflects word decoding, memory, inference making, or mental representations beyond the layperson’s cognitive resources.

Although these effects of the communication disparity might be obvious or easy to assess and troubleshoot, the disparity might also affect or bias the high-level functions in ways that are more subtle.

For example, pretend I’m a defendant sitting before a judge in a court hearing or a witness sitting before a lawyer in a deposition. Chances are good I do not want to appear ignorant or combative, and this desire may prompt me to prioritize acquiescent communication over correcting communication challenges. As a result, I might say I understand a question even if I do not have a particularly clear mental representation, or I might sign a document even if I do not understand all the words. In this way, the communication disparity might create a context that has both quantitative and qualitative communication challenges.

• Suboptimal contexts.10 People with legal concerns, especially adjudicated concerns, often are not at their cognitive best. They may be stressed and tired, which can limit the amount of lower-level cognitive resources such as memory and attention they can access. They may also be upset or unwilling to be in the legal context in the first place, and these “negative” emotions can color the mid-level and upper-level cognitive functions.

For example, if I am going through a messy divorce, my internal perceptions might “see” relatively neutral language in a settlement as unfair or insufficient because my mentalizing function now attributes deceptive intentions to my ex-partner. Or perhaps my internal representations during a dialogue with a judge reflect conversations with a friend who also went through a divorce and who told me how unfair the judge had been, so now I infer that the judge in my case will be unfair, too.

Another feature of legal contexts that can make them cognitively suboptimal is a lower tolerance for communication error than nonlegal contexts. If a tired person takes longer than average to respond to a question in a conversation at home, or tells a friend a story that is not entirely consistent, the behavior probably won’t matter. But if that same person takes longer than average to respond to a question or tell a story before a jury or to a lawyer, then the behavior could be interpreted in a way that triggers legal consequences. Like communication disparity, this risk factor can create both quantitative and qualitative communication challenges.

Cognitive-communication deficits and disorders often manifest as, or are interpreted as, behavioral or attitude shortcomings.

Individual Risk Factors. A wide range of personal factors can affect a given individual’s cognitive communication. Everything from being a poor reader to suffering from a head injury will influence how the cognitive networks in the brain work and how the person can access cognitive resources. As mentioned earlier, cognitive communication is a spectrum, and everyone will “start” at different places on that spectrum.

What makes cognitive-communication deficits especially worrisome, however, is that often they can be invisible. Unlike a speech impediment, which is immediately apparent, a deficit in working memory or a deficit in narrative making won’t necessarily have conspicuous behavioral manifestations: It will simply “look” like the person takes a long time to respond to questions, or has trouble remembering what was just said, or can’t keep their story straight.

This point is also worth reiterating: Cognitive-communication deficits and disorders often manifest as, or are interpreted as, behavioral or attitude shortcomings. It is well established that individuals with communication challenges are overrepresented within justice systems, particularly the criminal justice system,11 and this overrepresentation makes it even more important for legal professionals to be aware of how certain individual risk factors, such as the following, can affect communication.

• Adverse childhood experiences.12 Experiences such as childhood trauma or abuse might affect brain growth and development in a way that changes the brain’s function and structure, leading to effects at all levels of the cognitive-communication hierarchy, particularly those related to emotion and mentalizing. Relatedly, adverse childhood experiences can lead to poorer academic performance and behavioral challenges, which can further limit a person’s cognitive-communication resources.

• Brain injury and concussions.13 Brain injuries and concussions can cause physical damage to the brain in a way that disrupts the upper-level, mid-level, and lower-level cognitive function, and communication difficulties such as poor narrative, inability to mentalize, and memory deficits are common after a brain injury or a concussion. In addition, people with brain injuries or concussions can struggle with employment, school, time management, and social relationships, which might contribute to them facing social challenges and encountering legal professionals.

• Lack of education. Lack of education is not traditionally seen as a cognitive-communication deficit, but it can affect an individual’s ability to parse language (lower-level cognitive function), to have exposures to ideas or knowledge that they can use in their internal representations (mid-level cognitive function), and to communicate with appropriate pragmatics or narrative (upper-level cognitive function). Lack of education might also widen the disparity between the legal professional and the layperson, which in turn might further limit the layperson’s ability to participate in the communication.

By far the easiest and most effective thing you as a legal professional can do to facilitate communication is to slow down.

What Legal Professionals Can Do

Nobody expects lawyers to develop the skills needed to accommodate all cognitive-communication challenges. Nevertheless, lawyers bear the onus of representing their clients and ensuring that they can meaningfully participate in their legal proceedings. The following best-practice tips can help legal professionals reduce the effect that contextual risk factors might have and ameliorate the effect that individual risk factors might pose. These best-practice tips are not designed around any particular cognitive-communication disorder or any type of client: They can support communication and reduce challenges for anyone regardless of where that person lands on the spectrum of cognitive-communication ability.

-

Slow down. By far the easiest and most effective thing you as a legal professional can do to facilitate communication is to slow down. Slower communication puts less burden on lower-level cognitive functions like working memory and processing speed, it gives people more time to create internal representations and to “see” what they’re thinking about, and it gives them more time to plan and shape their own communication. It takes only about three seconds for the human brain to build a fully formed mental representation, so even small reductions in speed can make a big difference.

-

Cut superfluous information. Just as slowing down can reduce communication burdens, eliminating unnecessary material altogether can reduce the amount of communication that your client or party has to parse, internalize, and respond to. Blacking out or removing content on client’s copies of standardized forms, for example, can avoid confusion and help them focus their attention on the important parts of the communication.

-

Help your clients ground their information. One of the best things you can do to help overcome knowledge gaps is to provide tangible information that your clients can use to ground their own thinking. If they have never been in a courtroom, show them a picture so they can get a sense of what it will look like. If they have never dealt with bankruptcy before, find an educational video that uses illustrated graphics.14 If they are facing a restraining order, measure out the distance and say, “See the distance from my door to the end of the hall? That’s how far 50 feet is.” Anything you can do to provide accurate, perception-based information that your clients can use as the basis of their mental representations will make it easier and faster for them to communicate.

-

Don’t ask, “Do you understand?” Do ask, “Tell me what you understand.” As mentioned earlier, comprehension isn’t an all-or-nothing state. Not only can people have comprehension that is based on incomplete or inaccurate mental representations, but they also can lack the knowledge or information they would need to recognize that their mental representations are incomplete or inaccurate in the first place.

For example, there is compelling evidence that people routinely overestimate their own understanding of Miranda warnings,15 suggesting that, to them, their internal representations “look” perfectly fine even though they are technically incorrect. Because understanding is a dimmer switch and not an on-off switch, just asking “Do you understand?” collapses the spectrum of possible comprehensions and forces the person to distill their understanding into a one-word response.

Having a client or party tell you what they understand achieves two goals. First, it allows them the opportunity to share their internal mental representations with you. Again, because humans can’t rely on telepathic superpowers, the only way to truly know what is going on in another person’s head is to have them tell you. If you give your clients or parties the chance to explain their own understanding, you effectively give yourself the opportunity to check their mental work.

Second, an open-ended question helps reduce the fluency disparity that can be a context-based risk factor. Often, differences in communication ability (in addition to the social and authority dynamics, particularly in a courtroom) make legal contexts ones in which a person is all but guaranteed to just nod their heads and say “yes” when you ask, “Do you understand?” Asking “What is it that you understand?” can give people the time and space they need to form and deliver a response that better reflects what is inside their mind.

Conclusion

Cognitive communication is an inseperable aspect of the human social condition, and the law is no exception. By recognizing the types of cognitive and mental functions that drive cognitive communication, and by recognizing how these functions might interact with environmental or individual factors, legal professionals can be more aware of their clients’ or parties’ position and more aware of their own communication practices.

I appreciate that communication is a complex phenomenon: The information presented in this article is by no means comprehensive, and the cognitive functions that drive communication – not to mention the anatomy in which those functions reside – are much more dynamic and nuanced then my conceptual model would suggest.

That being said, no one has to be a neuroscientist to put this information to good use. Scientific evidence will continue to explain and explore cognitive communication, but legal professionals are already well positioned to use that evidence in a way that encourages more competent and mindful advocacy and representation throughout the course of everyday legal work.

Meet Our Contributors

You are an inaugural member of the U.W.’s JD/PhD dual-degree program in neuroscience and the law. What drew you to that combination?

I’ve been drawn to science and the scientific method since I was a kid, and I studied neuroscience as an undergraduate. But after serving in Americorps, I wanted to continue my science training and research in a way that offered a pragmatic, socially oriented perspective. It was serendipitous coincidence that the U.W. had only just created a dual-degree program in neuroscience and law as I was looking for options. As soon as I learned about it, I knew it was what I wanted to do. The U.W. has a rich legacy of progressive academic thinking, and being able to contribute to that ethos was both appealing and fulfilling.

I’ve been drawn to science and the scientific method since I was a kid, and I studied neuroscience as an undergraduate. But after serving in Americorps, I wanted to continue my science training and research in a way that offered a pragmatic, socially oriented perspective. It was serendipitous coincidence that the U.W. had only just created a dual-degree program in neuroscience and law as I was looking for options. As soon as I learned about it, I knew it was what I wanted to do. The U.W. has a rich legacy of progressive academic thinking, and being able to contribute to that ethos was both appealing and fulfilling.

Asked where or when I get my best ideas, I’d have to say I bike or run to and from work, and having that dedicated time to let my mind wander is pretty valuable. But like Edison said, it’s 99 percent perspiration. My "best" papers and studies weren’t anything close to blazing epiphanies; I just took rough ideas and worked on them over and over.

My favorite holiday destination? Tuscany. I love the history, the art, and the environment, and I’m hugely privileged to have two separate trips there this year alone. Closer to home, I really enjoy being up in the north woods. I spent time up there nearly every summer when I was growing up, so I associate it with fond memories of my family. And, I’m a tremendous softie. I never leave home without giving the dog a hug.

Joseph A. Wszalek, U.W.-Madison School of Nursing.

Become a contributor! Are you working on an interesting case? Have a practice tip to share? There are several ways to contribute to Wisconsin Lawyer. To discuss a topic idea, contact Managing Editor Karlé Lester at (800) 444-9404, ext. 6127, or email klester@wisbar.org. Check out our writing and submission guidelines.

Endnotes

1 See, e.g., U.S. Const. amend. VI.

2 See, e.g., Brady v. United States, 397 U.S. 742, 748 (1970); see also Miranda v. Arizona, 348 U.S. 436, 469 (1966).

3 See, e.g., Wis. Stat. § 756.02; see also Wis. Stat. § 905.015(1).

4 See, e.g., SCR 20:1.4; see also Model Rules of Prof’l Conduct R.1.4.

5 Note that the term “cognitive communication” typically excludes the brain’s functions that drive the physical aspects of communication, such as speech production.

6 See Joseph Wszalek, Ethical and Legal Concerns Associated with the Comprehension of Legal Language and Concepts, 8(1) AJOB Neuroscience 26, 27-29 (2017).

7 See id. at 32-33; see also Lyn S. Turkstra et al., Pragmatic Communication in Children and Adults: Implications for Rehabilitation Professionals, 39(18) Disability & Rehabilitation 1872 (2017).

8 For a summary, see Wszalek, supra note 6, at 26.

9 See Joseph A. Wszalek & Lyn S. Turkstra, Language Impairments in Youths with Traumatic Brain Injury: Implications for Criminal Proceedings, 30(2) J. Head Trauma Rehabilitation 86 (2015).

10 For a summary, see Wszalek, supra note 6, at 26 n.3.

11 See Anread Amodeo, Ying Jin & Johanna Kling, Preparing for Life Beyond Prison Walls: The Literacy of Incarcerated Adults Near Release, Am. Insts. for Research (June 2009); see also Michele LaVigne & Gregory J. Van Rybroek, Breakdown in the Language Zone: The Prevalence of Language Impairments among Juvenile and Adult Offenders and Why it Matters, 15(1) UC Davis J. Juv. Law & Pol’y 38 (2011).

12 See Carol Westby, Adverse Childhood Experiences: What Speech-Language Pathologists Need to Know, 30(1) Word of Mouth 1 (2018).

13 See Wszalek & Turkstra, supra note 9.

14 Several illustrated legal tools are available online for just this purpose. See Open Law Lab, http://www.openlawlab.com (last visited Aug. 4, 2019).

15 See, e.g., Richard Rogers et al., General Knowledge and Misknowledge of Miranda Rights: Are Effective Miranda Advisements Still Necessary? 19 Psychol. Pub. Pol’y & L. 432 (2013).