If you’ve ever met Derek Mosley, you have felt his open and welcoming vibe. The Milwaukee community certainly has. As a municipal court judge in Milwaukee County, Judge Mosley often spoke informally to the community, on social media, as “Your Friendly Neighborhood Judge,’” offering tips on how to stay safe and how to stay out of trouble.

On New Year’s Eve, for instance, Mosley mentioned that it was one of the worst nights for drunk driving. “Please be safe. With Free Buses, Uber, Lyft, and the Safe Ride Program, there is NO reason to get behind the wheel while impaired. Love, Your Friendly Neighborhood Judge,” Mosley wrote.

Around Independence Day, Mosley would post about the laws related to fireworks, in laypeople’s terms. “It started to catch on, and people would come up to me and be like, ‘hey, it’s the Friendly Neighborhood Judge!,” said Mosley, who has almost 5,000 followers on Instagram and nearly 15,000 followers on Facebook.

For Mosley, who recently stepped down from the bench, the role of judge can include civic and community leader. “I wanted people to have a positive experience when they saw me on the bench,” said Mosley, who has given many speeches throughout the community and at schools over the past 20 years.

“When I went to those schools, I would always wear my robe,” he said. “And people would always say to me, ‘you’re here to read a book at the school, why are you wearing your robe?’ I wore my robe because I wanted to normalize Black men in black robes.”

Now the director of Marquette University Law School’s Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education, Mosley is combining a love for his community with a civic leadership role that is connecting cultures and communities and addressing the public policy issues important to Wisconsinites. He takes over for Mike Gousha, who stepped back from full-time duties and now serves as a senior advisor.

Milwaukee is Home

A Chicago native, Mosley found his way to Marquette University for his undergraduate degree. “I fell in love with the city,” he said from his office at Eckstein Hall, overlooking the Marquette Interchange.

Joe Forward, Saint Louis Univ. School of Law 2010, is communications director for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6161.

Joe Forward, Saint Louis Univ. School of Law 2010, is communications director for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6161.

“This city is awesome. It has everything you want. The lakefront, the green space, amazing park systems, restaurants, the art museum, Summerfest. It’s just a great place.”

Thank actor Blair Underwood for Mosley’s decision to attend law school. Underwood played lawyer Jonathan Rollins on the hit television show L.A. Law, which aired from 1986 to 1994.

“I didn’t know any lawyers growing up,” Mosley said. “There were no lawyers in my neighborhood on the south side of Chicago. I didn’t even know what lawyers did. But when L.A. Law came on, I saw Jonathan Rollins played by Blair Underwood. He was the first Black lawyer I ever saw. And from that moment on, I wanted to be a lawyer. For all the wrong reasons, of course.”

Rollins had a BMW and a beach house, Mosley noted. “I was like, ‘I want that job.’ But then I got to Marquette Law School, and I realized exactly what I wanted to do, and that was to help the community.”

Mosley graduated from Marquette Law School in 1995 and took his first job as an assistant district attorney in Milwaukee County.

“I did everything, over a thousand criminal prosecutions,” he said. “I had a pretty long stint in children’s court, working with juveniles in the Milwaukee area, and a longer stint in drug court.”

Then he created the Community Prosecution Unit, evidence of his concern for the community at large. Prosecutors were stationed in community-based organizations throughout the city. “Those prosecutors became sort of the eyes and ears of the prosecutors downtown,” Mosley said.

“So when the police report says ‘the 200 block of North Palmer,’ for instance, the prosecutor in the field knows what’s going on in that community. It becomes more than just a street address, it becomes a person or families, Mrs. Johnson or the Smiths, whatever the case may be.”

He also began mentoring young people. “I got involved and got on the board of the YMCA, and met more youth, just through board involvement and interaction with the community,” he said. “I just fell in love with this city, with the residents and that’s what started my journey, and I didn’t want to leave.”

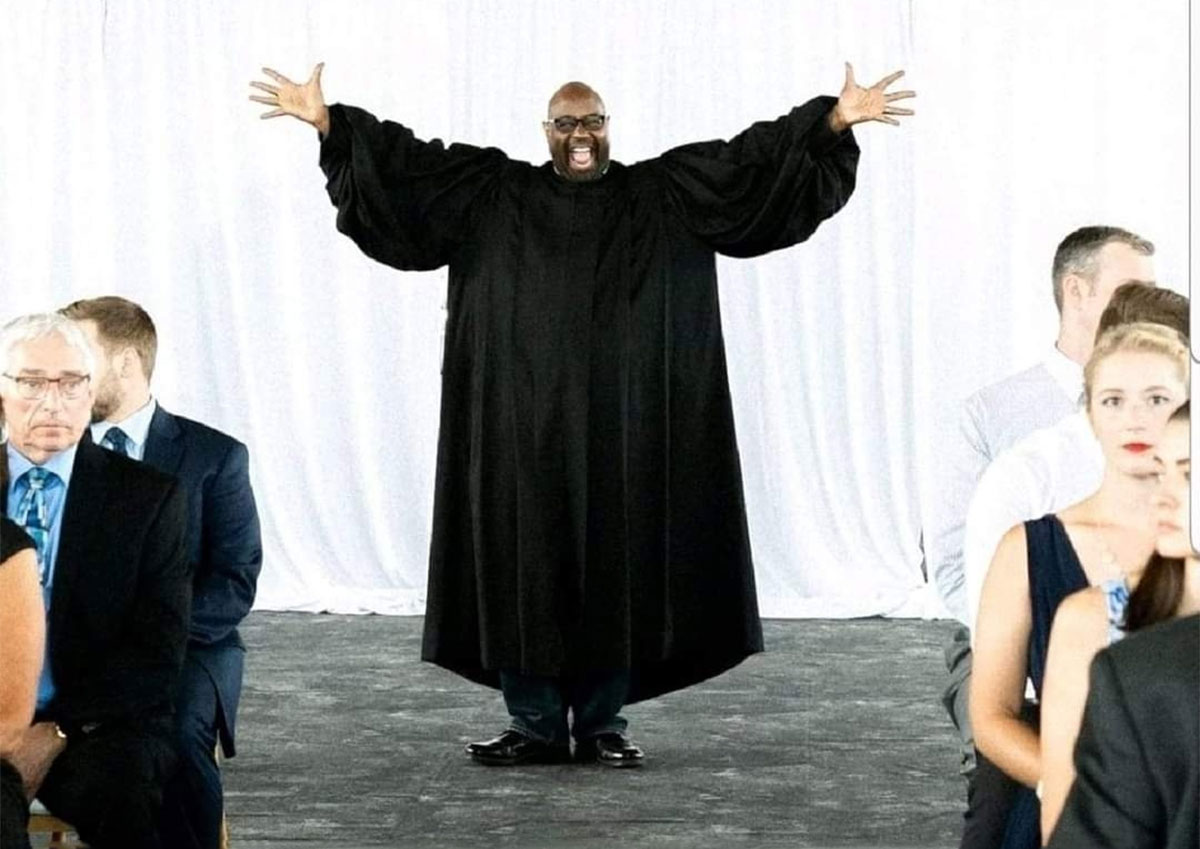

Former Milwaukee Municipal Court Judge Derek Mosley, prior to officiating a wedding at Discovery World in

Milwaukee.

To the Bench

After seven years as a prosecutor, Mosley decided to follow in the path of his mentor, Louis Butler, who served as a Milwaukee Municipal Court judge until his election to the circuit court bench in 2002.

That same year, Mosley was appointed to Butler’s seat on the municipal court and was elected and reelected to five four-year terms. When he was appointed, he was the youngest African-American to be appointed judge in Wisconsin. He would go on to serve 10 years as the municipal court’s chief judge.

Municipal court is where Mosley began to really shine as a community leader, and his visibility as an African-American judge was extremely important.

“Typically, especially in Wisconsin, when people of color come into courtrooms, nobody looks like them. The judge doesn’t look like them, their attorneys don’t look like them, the opposing counsel doesn’t look like them,” said Mosley.

“And so it was nice to see the look on the faces of people when they walk in, because they feel like, ‘I’m going to be heard! Someone understands me, knows what I’m going through and I’m going to be heard!’” Mosley explained. “That’s what got me really involved in the community at that point. Because now I’m being asked to go speak in different groups, different locations, to talk about the system.”

Of course, judges must deliver bad news in many cases. But Mosley saw the job as more than judgments. “I wanted to be synonymous with that court, and I wanted it to be a positive experience when you thought about me and that court,” Mosley said. “That was the first thing.”

“Second, I wanted to demystify the system for those coming into the court,” he said. “Because [as] I’ve mentioned, ever too often, people enter the court system, and they don’t feel comfortable because nobody in the courtroom looks like them.”

Mosley said diverse judicial appointments are a good thing. “When [people] walk into a courtroom and they see someone who looks like them, at least they feel as if they’re going to get a fair shot,” he said.

As “Your Friendly Neighborhood Judge” for two decades, Derek Mosley often used

the robe to demystify the court system. Now he takes on an expanded role in

connecting the community.

The Next Generation

The premise of “Your Friendly Neighborhood Judge” was access to and understanding of the court system, and Mosley used the robe to demystify the judicial system when he visited schools.

“I’d bring this giant gavel, and as soon as I walk in with this giant gavel, the kids would look at it, and they’d love it when they see someone like themselves, who was a judge,” Mosley said.

“That’s how I got here. Except the person I saw, Jonathan Rollins, wasn’t even real. He was an actor on a TV show, and you know, I’m real, flesh and blood, and I wanted the kids to see that.

“In many neighborhoods in the city, they don’t see that. They’re like me in a sense and they didn’t see judges, they didn’t see Black men in a positive light, and so it was important that I did that.”

When juveniles would come to Mosley’s court, he’d ask them: What do you want to be when you grow up? “Almost 90% of the time, they’d say ‘I want to play for the Bucks!’ It used to be the Packers, but then Giannis came, and then it was the Bucks,” said Mosley. “But that’s what they see.”

To encourage young people to think about more possibilities, Mosley helped resurrect the MEDAL program, which exposes middle-school students to five professions: medicine, engineering, dentistry, architecture, and law.

The partnership between the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee School of Engineering, Marquette Dental School, Milwaukee Area Technical College, and Marquette Law School introduces children of color to these professions through a week-long program, with a half-day devoted to each profession.

“So on Monday, we go to the Medical College of Wisconsin,” Mosley said. “They get the white jackets. They go on fake rounds with doctors, sit in the classroom, and see what it’s like to be a medical student. I have a panel of all students of color, so they can see medical students that look just like them.”

The children get a similar experience at the other professional schools. “You get to talk to them, you get to listen to what they say. You see the look on these kids’ faces when they see Black women and Black men and Latino men and women who look just like them, it’s a game changer!”

Second Chances

Mosley, as a community leader and judge, has made plenty of headlines with his good work in the community, his social media presence, and his upbeat spirit. Other stories have focused on serious illnesses and Mosley’s second (and third) chances at life.

In 2016, facing kidney failure, Mosley, at 46, needed a kidney transplant. Friend and colleague JoAnn Eiring, a town of Brookfield municipal court judge, became his lifeline, donating a kidney to him.

The story made national headlines. Fast-forward to March 2020, and Mosley faced another challenge: COVID-19. “I’ll never forget this. I’m in the hospital, I’m in the ICU, and you are completely secluded. No one comes in to see you, nurses come in but they’re in full garb,” he said. “You can only see their eyes.”

“And I’m watching the news, I’m just seeing people on the news, talk about how this is fake, this isn’t a real thing, they made this up. And I’m watching as they take the beds out of rooms, because people have died in the ICU while I’m there.” He was struggling to breathe and needed a ventilator.

The night before Mosley was put on a ventilator, a nurse came into his room. “She handed me an iPad, it was my wife and kids,” Mosley recalled. “My wife probably knew, but my kids didn’t know. I thought, ‘this is going to be the last time we speak.’”

“We laughed, we cried, everything, and then they left. It was the most powerful experience. To this day, it’s still emotional for me. There’s nothing like telling your family goodbye, nothing like that.”

But he began to recover. “I think it had a lot to do with that nurse who came in, who sat down and held my hand all night. When I got better and was released, I knew I’d gotten a second chance.”

Typically, especially in Wisconsin, when people of color come into courtrooms, nobody looks like them. The judge doesn’t look like them, their attorneys don’t look like them, the opposing counsel doesn’t look like them.

Civility and Community

In 2023, Mosley took his new post as director of Marquette Law School’s Lubar Center, a public policy and civic education initiative established with an endowment from Sheldon and Marianne Lubar.

The Lubar Center serves as a forum for public and civil discourse, hosting lectures, conferences, and events to shed light on issues of public importance. One program Mosley is spearheading is called Heritage Dinners, gatherings to bring together the community’s diverse population.

In February, for Black History Month, Mosley coordinated “For the Soul: A Narrated Food Tasting and Conversation.” Mosley and guests explored the history of African-American food culture, as introduced to the American palate, as local chefs prepared African-American inspired dishes.

“It was one of the events in Milwaukee that you’d just have to see to believe. Age diversity, ethnic diversity, gender diversity, sexual-orientation diversity, everybody was in this room,” Mosley said.

“We had stations set up where you get the food, and [I] and a DJ from HIFIN radio from Milwaukee … gave a historical narrative of what you’re going to eat.”

The inspiration for May’s Heritage Dinner is Asian-American cuisine and history. “We’re going to have Chinese, Japanese, Hmong, Thai, Lao, chefs preparing the food, with a brief history of what is there,” Mosley said. “We’re introducing cultures that might not otherwise connect with each other.”

The Heritage Dinners are just a small taste of what Mosley has planned for the Lubar Center’s work. But Mosley said he wants to focus on civility and civil discourse.

“Shel Lubar was the impetus behind the center,” Mosley said. “He gave the money for the center to be started and his whole thing was, ‘we lost civility.’ We’ve lost civility in our society where we can disagree, but now we’re disagreeable. You can disagree, but you don’t have to be disagreeable.

“These events will center on the rule that you can come in here, you can speak your truth, but we do it through informed, intellectual, and civil discussions. Who would not want that?”

Lawyers, he said, can help drive those discussions. “Just think of the knowledge that lawyers in our community have, and the positions of power.

“Not all lawyers are practicing law,” he said. “Some are legislators, teachers, and business leaders. I just think in those positions, in those platforms, they can have a huge effect on what’s going on in society.”

Mosley will also bring the larger community to the Lubar Center. “Because these issues affect us all. Water, education, poverty, housing, transit, all these issues affect all our residents and sometimes residents don’t feel like they have a say in these matters,” Mosley noted.

“So we’re bringing them into the Lubar Center to be part of these conversations, to ask the questions to the policy makers and help them be a part of the process. Isn’t that what it’s all about?”

Onward

This isn’t the first or last you’ll learn about Derek Mosley. The former fan of L.A. Law’s Jonathan Rollins, assistant district attorney, and municipal court judge and current Lubar Center director recently was named one of the Milwaukee Business Journal’s 2023 Top Power Brokers. As in, someone who makes things happen.

Mosley says he wants to make the most of this second life, even though his wife sometimes tells him to slow down. “Because I shouldn’t be here,” Mosley said. “And so, it’s important for me to up the ante. I thought I was doing a lot, but apparently there’s more to be done.”

» Cite this article: 96 Wis. Law. 10-13 (April 2023).