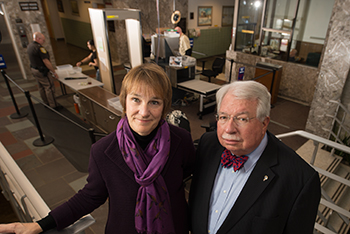

Lisa Neubauer, Judicial Study Committee chair, and Michael Bohren, cochair of the Court Security Subcommittee of the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s Planning and Policy Advisory Committee. Photos: Kevin Harnack

A man who had threatened to kill prosecutors and any witnesses who dared to testify against his friend walked into a Wisconsin courthouse, where he encountered no weapons screening. He proceeded to park himself outside the district attorney’s office. Hours later, after he became increasingly agitated, deputies frisked him and found he was carrying two knives.

In another incident, a citizen with a grudge entered the clerk of court’s office and walked up to an unsecured front counter. His hostile behavior soon caused the office staff to feel threatened enough to call local law enforcement. By the time officers arrived on the scene, 20 long minutes had elapsed, during which the man fortunately had not harmed anyone.

And in yet another episode, the weapons scanner at a courthouse entrance went off when someone approached. The security guard, who had no law enforcement training, shrugged and waved the person through, commenting, “It’s probably your shoes.” The person who was seeking entrance, a plain-clothes police officer, looked the security employee in the eye and responded, “No. It’s my gun.”

These are just a few incidents detailing the inadequate security staffing in Wisconsin courthouses, as reported by respondents to a recent State Bar of Wisconsin survey on court funding. Overall, the survey found that:

50 percent of respondents feel courthouse security staffing is “less than adequate.”

When broken down by position in the court system, 58 percent of judges deem security staffing to be inadequate, as do 62 percent of administrators and 43 percent of attorneys.

Concerns about lack of security staffing rank highest among respondents from jurisdictions with populations of 50,001 to 100,000 (60 percent of respondents) and 50,000 or less (56 percent).

Court staffing security was just one issue examined in the survey, which was commissioned by the Judicial Funding Subcommittee of the State Bar’s Bench and Bar Committee.

The accompanying sidebar on page 18, “More Findings From Court Funding Survey,” provides information about the survey’s objectives and methodology, as well as additional survey results on how inadequate funding affects courts’ ability to deliver justice.

Security Measures are Voluntary Only

Court security has long been on the radar of Michael Bohren, a circuit court judge in Waukesha County for 15 years. He co-chairs the Court Security Subcommittee of the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s Planning and Policy Advisory Committee (PPAC). In 2010, the subcommittee released a report on its survey of court security across the state, which led to the adoption in 2012 of Supreme Court rules (SCR) chapter 68.

The rules provide recommendations on court security and stipulate that each Wisconsin county must create a Court Security and Facilities Committee. The PPAC security subcommittee also hosts an annual conference at which county officials, law enforcement, and judicial officers share security best practices.

Any security measures a county implements, however, are voluntary and get done on the county’s dime.

“Local control has always been a hallmark of our approach,” Bohren says. “The key is for judicial officers to work closely not only with their county board and county executive, if there is one, but also with the sheriff.”

“Court security works the same way. It’s like an insurance premium, and it costs money each year to be able to maintain it.”

Judge Michael Bohren, Waukesha County Circuit Court, co-chair of the Court Security Subcommittee of the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s Planning and Policy Advisory Committee.

Thus, what does or doesn’t happen to make county courthouses more secure ultimately lies in the hands of county government officials. Some rural counties may assume violence won’t happen in their courthouses. The reality is that shootings have occurred in court-houses in small counties across the country, Bohren points out, even resulting in judge assassinations.

Budget-strapped counties increasingly struggle to meet their responsibilities to fund court facilities, which includes paying for court security. From fiscal year 2008 to fiscal year 2015, the counties’ share of circuit court-related spending climbed from 54 percent to 63 percent, according to statistics from the State Courts Office.

Still, funding court security is like paying for insurance on your home, Bohren points out. “We buy fire insurance, but few houses actually burn down,” he says. “If yours does, however, and you have no insurance, you’re in a terrible mess. Court security works the same way. It’s like an insurance premium, and it costs money each year to be able to maintain it.”

Rage Comes to Court

The quandary over court funding and who will fund how much of it is common in jurisdictions across the country, says William Raftery, an analyst with the National Center for State Courts, Williamsburg, Va. “There’s sort of a push-pull dynamic between how much is expected from the state versus the local or county government,” he says.

As noted, that dynamic plays out in Wisconsin, as well. An issue paper from the Wisconsin Counties Association puts it this way: “The burden of funding state court operations has shifted from the state to counties significantly since 2009. At the same time, counties have had to cope with growing demands for county services and other financial constraints.”

Tell Us!

Witnessing the effects of insufficient court funding? Share your observations with State Bar Public Relations Coordinator Katie Stenz at kstenz@wisbar.org or post a comment below.

Similar circumstances exist nationwide, Raftery says. But, he adds, a few states are trying new security solutions.

“Some states have stepped in to create court security funds,” he says, “because the local and county governments either can’t or won’t provide sufficient security.” For instance, Maine and Colorado set up special court security funds financed by either a state legislature appropriation or a blend of legislature appropriation and court fees.

Wherever the funding comes from, Richard Sankovitz, a circuit court judge in Milwaukee County, finds the “there’s no money” argument a bit hard to swallow. “Lack of funding is an excuse, not a reason,” he says. “Another way of saying that is, what’s our priority? We’re funding a new basketball arena and freeways.”

Courthouse security gets shunted down the priority list when decision-makers see it as not being a concern, or at least not a big enough concern. That’s a poor decision, Sankovitz says, based on the evidence of violence erupting in locations ranging from small towns to large cities across the country. And the situation is getting worse.

“We have a gun problem in this country, and that goes back to a deeper issue. We have an anger problem, a rage problem. When people come to court, they sometimes bring their anger and rage with them. Things boil over from time to time.”

Judge Richard Sankovitz in a Milwaukee County courtroom. Photo: Wisconsin Law Journal / Kevin Harnack.

“We have a gun problem in this country, and that goes back to a deeper issue,” Sankovitz says. “We have an anger problem, a rage problem. When people come to court, they sometimes bring their anger and rage with them. Things boil over from time to time.”

Milwaukee County has made good strides in court security, Sankovitz says, largely through the persistent efforts of judges Jeffrey Kremers, Michael Skwierawski, and Kitty Brennan. For instance, courthouse perimeter security is strong, and a security wall now separates the gallery from the rest of the courtroom.

Sankovitz is now doing a civil court rotation, so a bailiff is not routinely assigned to his courtroom. “But our sheriff is very good about making a bailiff available,” Sankovitz says, if he requests one.

Still, problems persist. As one example, defendants are escorted through open hallways on the way from the jail to the courtroom, posing safety risks. Narrow hallways outside courtrooms entrap adversarial parties in the same confined space, putting them at risk. Tempers flare, and fights erupt.

Every county faces its own challenges, but there’s one common denominator for all, in Sankovitz’s view. “We need the political and fiscal willpower to say, yes, there are risks, and how much is it worth to prevent losing a life? Our courthouses will fail to function if people see them as dangerous places and are afraid to go there.”

Dealing With People’s ‘Tipping Points’

With a population of about 57,000, Columbia County is among those counties where survey respondents expressed the highest level of concern about insufficient court security staffing. Still, Columbia County is doing more than many to make progress in shoring up overall court security.

“We received excellent feedback from folks working in all aspects of the court system. The State Bar now can work with all the stakeholders to determine the priorities and develop a plan to address the funding shortfalls.”

Lisa Neubauer, chief judge, Wisconsin Court of Appeals, and chair of Judicial Study Committee.

For instance, the county has approved a major building project that entails constructing two new buildings to house all noncourt-related functions. Court functions will remain in the 53-year-old courthouse, which will undergo some security improvements.

“We had done about every free or low-cost thing we could do,” says Andrew Voigt, a circuit court judge and chair of the county’s committee on courthouse security. “We were at the point where we had to undertake some projects with significant budgetary impact.”

As for the current security staffing level, the courthouse is assigned a deputy sheriff, although the deputy is not in the courthouse full-time. Part-time employees, who are retired law enforcement officers, oversee a screening station at the courthouse entrance, but not all day every day. “They do screening at random,” Voigt says, “but even that is a significant improvement for us.”

Annual or semi-annual training of courthouse personnel also has improved the situation. Training is one of the recommendations put forth by SCR chapter 68 on court security. The goal is to give employees practice in responding to various scenarios to better prepare them should a real-life crisis strike.

“We’ve had employees who have responded in ways that put them in more danger, not less,” Voigt says. “We’re happy they’re doing that in this type of controlled setting” rather than during an actual threat.

“We had done about every free or low-cost thing we could do. We were at the point where we had to undertake some projects with significant budgetary impact.”

Judge Andrew Voigt, Columbia County Circuit Court, and chair of the county’s committee on courthouse security. Photo: Shannon Green

When a circuit court shares the courthouse with other agencies, as is the case in Columbia County and many others, those agencies’ employees also receive the training, not just court employees. And that serves another purpose, Voigt says.

“They can add their voices,” he notes, “to say, ‘I didn’t realize how big this problem is.’ Then it’s not just the judges or sheriff going to the county board” to ask for more security staffing and funding.

The biggest misconception about court security, in Voigt’s view, is that it’s solely a problem in criminal court. Divorces, custody battles, parental rights terminations, and many other legal matters generate tensions.

“Some people get fired up about who gets mom’s china after she’s died,” Voigt says. “Sometimes the strangest things are the tipping point for people, and we keep inviting them to this building – and to some 70 other buildings like it across the state.”

Although he’s dealt with no actual violence in his courtroom and its environs, Voigt has experienced situations that made him uneasy: raised voices, veiled threats, inappropriate comments, and more.

Survey Respondents: Security Staffing Shortcomings

Write-in comments from respondents to the State Bar Survey on Court Funding give a glimpse of the security staffing shortcomings seen in many counties. As just a small sampling:

“Anyone can walk in with a weapon.”

“Hearings that should have security [personnel] often do not have them.”

“There is an ongoing dispute between the chief judge and the sheriff about bailiff staffing.”

“We have rent-a-cops for courthouse security to save money. Their training is inadequate to face a crisis.”

“Someday someone in our courthouse will be shot. Our county is not doing enough to provide security to litigants, witnesses, attorneys, members of the public, and clerk staff – because there is no money.”

“It’s difficult in my mind,” he says, “to get past the fact that I now have as a daily goal – for myself, my coworkers, and all the litigants and lawyers who appear before me – to go home safe at the end of the day. That’s a strange thing to have to think about. Not that long ago, that kind of concern was reserved for people in such occupations as law enforcement and firefighting.”

Too Many ‘Near Misses’

The State Bar survey found that among lawyer respondents, those voicing the most concern about court security staffing were district attorneys and assistant district attorneys. More than two-thirds of them say security staffing is inadequate.

David O’Leary, the district attorney in Rock County, is one of them. As chair of the Wisconsin District Attorneys Association, he also hears from other district attorneys about their security concerns.

He describes security at the Rock County courthouse as an “illusion of security.” When the courthouse security committee meets, “We pretty much have the understanding that it’s not a matter of ‘if’ but ‘when’ [a violent event will occur] and who is at risk.”

The front entrance has a security station staffed by unarmed, mostly retired former law enforcement officers. If there’s trouble, they must get on the radio to summon sheriff’s deputies, and it can take a while for help to arrive.

“If someone comes into the building armed and intending harm,” O’Leary says, “the security staff can’t stop them. They’re not trained, armed law enforcement officers. The cynical comment we sometimes hear around here is that they’re basically speed bumps. The individual can blow right past security and continue into the building.”

The current staffing arrangement is cheaper, O’Leary points out, than having deputies present. When it comes to security hiring, “It’s the lowest bid wins,” he says. “It all boils down to funding.”

“If someone comes into the building armed and intending harm, the security staff can’t stop them. They’re not trained, armed law enforcement officers. … The individual can blow right past security and continue into the building.”

David O’Leary, Rock County District Attorney, is chair of the Wisconsin District Attorneys Association.

He reports that many “near misses” have occurred in the county’s courtrooms, some of which resulted in injuries, but could have turned out deadly.

For instance, in one case an individual angry about the way court proceedings were going started a fight with the bailiff, who ended up with a broken foot. In another incident, on being found guilty, a man tried to commit suicide in the courtroom by swallowing a large amount of pills. The bailiffs dealt with him while the victim of the crime and the district attorney’s victim witness coordinator ducked out the door, only to be confronted by the defendant’s angry family members in the hallway.

“My victim witness coordinator was putting herself between the victim and the upset family members, trying to keep security in the hallway,” O’Leary recalls, “while all hell was breaking loose in the courtroom.”

And it’s not just court-related people who are at risk, he adds, but also those affiliated with other agencies within the courthouse. Persons who are upset with a court official may not be able to get to that person. So they confront the first person they run across.

“They’re mad at ‘them,’” O’Leary points out. “And if you’re in the courthouse, you’re one of ‘them.’ They’ll take out their anger on anyone they can get their hands on.”

Dianne Molvig is a frequent contributor to area and national publications.

O’Leary hears stories such as these from district attorneys all over the state. He knows that some have given their assistant district attorneys permission to conceal and carry for their own protection. Some judges also keep a gun at the bench. That seems a questionable solution to O’Leary.

“I’m concerned about adding more weapons into a volatile situation,” he says. “The bullets start flying, and anybody can be in the line of fire. My preference is to have security in the hands of sworn, armed law enforcement officers who are trained to protect and serve.”

The best strategy, O’Leary adds, is doing the utmost to prevent more of those “near misses” – or worse. As a district attorney, he’s accustomed to being involved in the process that plays out in the wake of a violent act. He doesn’t want such an event to happen in the courthouse, with people hurt or killed.

“Let’s not wait until this lands on my doorstep,” he says. “Let’s prevent it.”

More Findings: Inadequate Court Funding Affects Ability to Deliver Justice

By Dianne Molvig

The judicial branch is invisible to ordinary citizens – until they need it when life throws them a curve. They get fired from their job for no good reason. An irate customer sues their small business. Or they need a restraining order against an ex-boyfriend who’s making dangerous threats.

Lack of public awareness of the court system makes it an easy target when politicians are looking for places to cut budgets. In Wisconsin, less than one penny of each tax dollar goes to the courts – 0.85 percent of a penny, to be more precise. The state court system’s budget is just under $138 million for each of fiscal years 2016 and 2017, according to the State Courts Office.

Meanwhile, state courts generate money for the state, points out William Raftery, an analyst with the National Center for State Courts, Williamsburg, Va. It’s common, he says, for courts to bring in $1 million or more a year in fees and fines, but that money doesn’t stay with the courts. It goes to help cover other state operating costs.

“It becomes a matter of ‘How can we get more revenue out of the courts without paying enough to operate the courts?’” Raftery says. “This is an issue of fairness and access to justice. Courts are not meant to be revenue generators. They’re meant to be places for fairness and impartiality.”

In line with that, the State Bar of Wisconsin set a strategic goal of finding ways to promote the public perception of the judiciary, in order to improve the administration of justice for everyone.

“We identified many different challenges to the public perception of a fair and impartial judiciary,” says Ryan Stippich, a Milwaukee attorney and chair of the State Bar’s Bench and Bar Committee. “Court funding is one of them.”

Tapping Diverse Perspectives

The Bench and Bar Committee decided to find out exactly how court funding was affecting Wisconsin courts’ ability to deliver justice. That information-gathering task was put in the hands of the Judicial Funding Subcommittee, which contracted with the St. Norbert College Strategic Research Institute to conduct a survey in spring 2015.

The survey’s results came from a random sampling of 2,200 individuals in the court system – including judges, court commissioners, district administrators, clerks of court, district attorneys, and other lawyers from across the state. Of those who received the survey, 706 completed and returned it, for a 32 percent response rate.

“We received excellent feedback from folks working in all aspects of the court system,” says Lisa Neubauer, chief judge of the court of appeals and chair of the Judicial Funding Subcommittee. “The State Bar now can work with all the stakeholders to determine the priorities and develop a plan to address the funding shortfalls.”

Some of the survey’s other key findings include:

70 percent of respondents say the current level of funding for courts in their jurisdiction is “less than adequate.”

63 percent of those who say overall funding is less than adequate also say that funding levels are doing a worse job at meeting the needs of delivering court services today compared with five years ago.

74 percent say it’s “very important” for the courts to have additional funding in order to meet the courts’ needs.

58 percent of judges say staffing for court-appointed attorneys is inadequate. 43 percent of lawyers and 43 percent of administrators also hold that view.

64 percent believe additional funding for technology is very important.

49 percent say they need more funding for certified court interpreters.

45 percent deem funding for court-appointed experts as

inadequate.

46 percent believe that more funding for pro se support is very important.

Day-to-day Impacts

Because at least 90 percent of court funding typically goes to personnel, when courts face insufficient funding that’s where cuts occur, explains Raftery. “The first cuts happen at the staff level,” he says, “and the second cuts, the third cuts, the fourth cuts.”

How does this situation play out in daily court functioning? Two members of the Bar’s Judicial Funding Subcommittee speak to that question from different perspectives.

Kathleen Madden, clerk of court in Waukesha County, reports that because of budget constraints and declining revenues, “Our workforce has been reduced 16 percent over the past decade.”

The list of lost employees includes a court reporter, a court commissioner, a social worker in family court services, and several clerical positions, all funded by the county. The cuts are “necessary,” she says, “because every year we face a $200,000 to $300,000 hole in our budget.”

Waukesha County now supports 60 percent of the circuit court’s costs. “The state’s share has gone down year after year,” Madden says, “so the county takes on more and more.” That’s especially difficult, she adds, when the county levy increase has been zero percent for the past two budget cycles, and 2016 will bring a levy reduction.

Kelli Thompson, director of the State Public Defenders Office, knows that inadequate court funding has an effect on her agency’s ability to perform well.

“When court funding is inadequate,” she says, “the justice process slows down. That directly impacts our clients, who perhaps sit in jail longer waiting for a trial. It impacts our attorneys, who have extraordinarily high caseloads, and have to waste time going back and forth to court more often because of delays.”

Insufficient funding for interpreters, experts, court clerical staff, and so on also affects the public defenders’ functioning, Thompson adds. For instance, more cases have lots of technical issues, she notes, so staff attorneys need transcripts. They also need testimony from experts.

“It’s all those things that are not at the front of the store, but at the back,” Thompson says. “We can’t do our work without them. And insufficient court funding makes it difficult.”

Future articles in the State Bar’s WisBar InsideTrack online publication will explore survey findings in more depth, as well as the impacts of inadequate court funding.