Wisconsin’s waters have been protected since before it was a state. The concept of the public trust doctrine, or the state holding navigable waters in trust so they remain forever free and open to the public, was passed down from the Northwest Ordinance to the Wisconsin Constitution, article IX, section 1.1 State statutes have since been crafted to protect Wisconsin’s groundwater and surface water and to give the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) primary responsibility for overseeing this resource.

Wisconsin’s waters have been protected since before it was a state. The concept of the public trust doctrine, or the state holding navigable waters in trust so they remain forever free and open to the public, was passed down from the Northwest Ordinance to the Wisconsin Constitution, article IX, section 1.1 State statutes have since been crafted to protect Wisconsin’s groundwater and surface water and to give the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) primary responsibility for overseeing this resource.

But Wisconsin’s waters are facing a threat: they are being dried from the bottom up. As high-capacity wells proliferate in Wisconsin, water in groundwater-fed streams and lakes is being diverted to these wells beneath the surface, reducing surface water levels and stream flows. At the same time, the DNR has been working to implement Lake Beulah Management District v. DNR, the 2011 Wisconsin Supreme Court decision that held the DNR “has the authority and a general duty to consider whether a proposed high capacity well may harm waters of the state.”2

This article explains the legal basis for Wisconsin’s groundwater regulations and legal developments since the Lake Beulah case was decided. It also previews potential legislative action concerning this often unseen – but increasingly consequential – natural resource.

Wisconsin Groundwater Quantity Laws and Lake Beulah

Wisconsin has declared a policy of enhancing the quality and protection of all waters of the state. This policy extends to groundwater, or water below the earth’s surface that originates from rainfall percolating through the soil, but that can sometimes be pumped faster than it is replenished. The Wisconsin Legislature has granted necessary power to the DNR to organize a comprehensive program to achieve the state’s policy.3

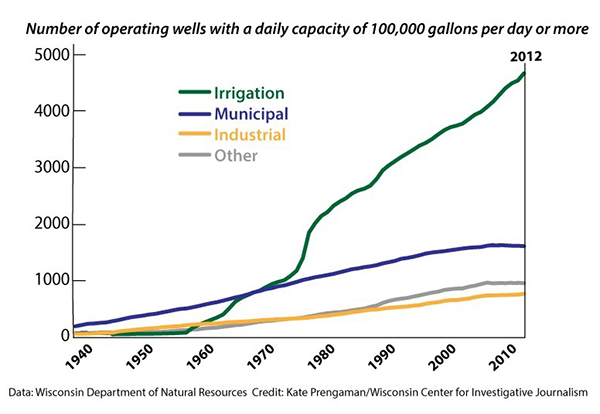

One component of this program is regulation of high-capacity wells, or wells that (alone or together with other wells on the same property) can pump more than 100,000 gallons of water per day. These wells require a permit from the DNR before construction.4 Surface water withdrawals, wells that are located in the Great Lakes Basin, and wells that can pump more than 2 million gallons of water per day are subject to different or additional requirements not discussed in this article.5

Research has connected these withdrawals to flow reductions and drying of streams and lakes in the Central Sands, beyond effects attributable to climate or natural fluctuations.

The DNR’s high-capacity well permitting authority is under Wis. Stat. section 281.34 and specifically requires the agency to conduct an environmental review for wells located within 1,200 feet of a trout stream or outstanding or exceptional resource waters, wells that remove most of the water from a basin, or wells that could significantly affect a stream. The DNR may deny or place conditions on wells that would affect these areas and on wells that would impair a public water supply. Wells are also subject to construction, location, and other requirements under the Wisconsin Administrative Code.7

Christa Westerberg, U.W. 2002, is a shareholder at McGillivray, Westerberg & Bender LLC, Madison. The firm’s emphasis is in environmental, civil rights, and open government law. She has represented citizens’ groups and other entities in high-capacity well permitting actions.

Christa Westerberg, U.W. 2002, is a shareholder at McGillivray, Westerberg & Bender LLC, Madison. The firm’s emphasis is in environmental, civil rights, and open government law. She has represented citizens’ groups and other entities in high-capacity well permitting actions.

The agency has additional duties related to wells. In Lake Beulah, the Wisconsin Supreme Court reviewed the DNR’s well-permitting authority under statute and the public trust doctrine. The court unanimously determined that when presented with sufficient, concrete scientific evidence that a proposed high-capacity well might harm waters of the state, the DNR has the authority and general duty to investigate or consider the environmental impact of the well. The information can come from state residents, the applicant, or even the DNR itself and should ideally be supplied while the well application is under review. In some cases, the DNR must deny the permit application or include conditions in a well permit.8

Once well permits are granted, they remain in effect indefinitely, unless modified or rescinded by the DNR. Permittees must submit an annual pumping report identifying, among other things, the amount of water pumped; results are available in a searchable database on the DNR’s website.9

Recent Legal Developments

After Lake Beulah, the DNR began screening all proposed high-capacity wells for potential effects on waters of the state, and sometimes imposed conditions on well permits to mitigate or monitor effects. The DNR also posts recent high-capacity well applications on its website to provide information and facilitate public access to the review process described in Lake Beulah.10 Yet the DNR’s process has been subject to challenge, particularly in Wisconsin’s Central Sands region.

High Capacity Wells by Type in Wisconsin6

Click image to view larger version.

The Central Sands lies between the Wisconsin River to the west, and the headwater streams of the Fox and Wolf Rivers to the east. It contains many high-quality water resources, including groundwater-fed trout streams, kettle lakes, and wetlands. It is also home to the state’s largest concentration of high-capacity wells – approximately 2,500 – in part because of the area’s sandy, well-drained soils.

Both the number of well applications and the amount of water pumped have increased over time. In 2013, total withdrawals for irrigation statewide were 101 billion gallons; in 2012, which saw a summer drought, withdrawals reached 135 billion gallons.11 Research has connected these withdrawals to flow reductions and drying of streams and lakes in the Central Sands, beyond effects attributable to climate or natural fluctuations. For example, Long Lake in Plainfield, which previously had a maximum depth of approximately 10 feet, dried completely in 2006. The Little Plover River, a high-quality trout stream, was near dry in 2003 and has dried annually in stretches since 2005.12

Two recent high-capacity well applications in the Central Sands have been subject to legal challenge – one by the permittee, and one by neighbors who had already experienced drawdowns in nearby surface waters. Both concerned permits for large-scale dairies proposed by Milk Source Holdings LLC in Adams County.

Proposals included limiting DNR permitting authority, exempting or grandfathering existing wells from future regulations, and defining remedies for harmful groundwater withdrawals.

In the first case, the DNR granted a modified high-capacity well permit to New Chester Dairy to facilitate its expansion from 4,300 cows to 8,600 cows, making it one of the largest dairies in Wisconsin.14 Because the increased water withdrawal necessary for the dairy could have a significant adverse effect on the nearby Patrick Lake, the dairy conducted groundwater modeling to show the wells at their proposed location would not harm the resource. Though the DNR granted the permit, there were enough uncertainties in the modeling analysis that the DNR required New Chester to conduct groundwater monitoring near the site to confirm the model’s predicted effects on the groundwater table. The permit required monitoring for three years, with results to be reported to the DNR.

In an administrative contested-case proceeding, New Chester Dairy challenged the DNR’s authority to require monitoring and the reasonableness of the monitoring conditions themselves. The administrative law judge (ALJ) determined on summary judgment that the DNR had express authority under statute, regulation, and case law to impose the monitoring conditions, including under Wis. Stat. section 281.11 and the Lake Beulah decision.

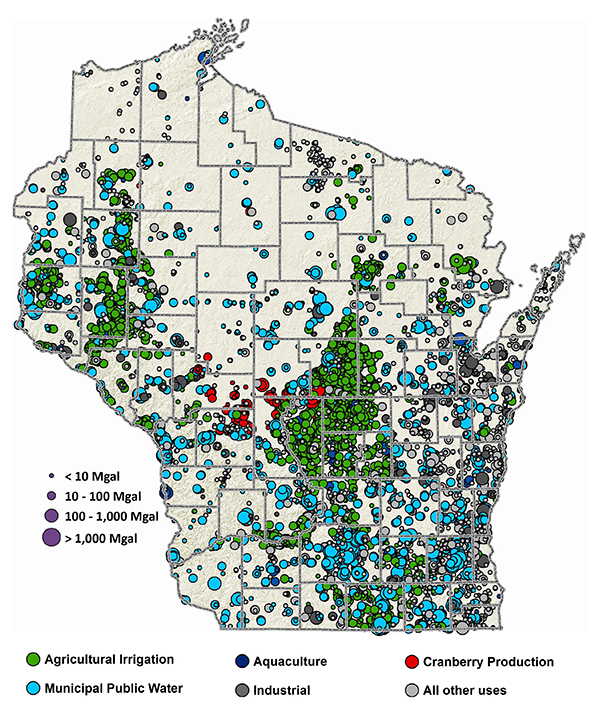

2013 Groundwater Annual Withdrawls13

Each circle represents a single 2013 point of withdrawal. The size of the circle varies according to the total 2013 volume of groundwater withdrawn from that point.

Click image to view larger version.

After an evidentiary hearing, the ALJ also determined that the permit monitoring conditions were reasonable and necessary to ensure the wells would not have a significant adverse effect on nearby waters of the state, and that the conditions were supported by substantial evidence.15 New Chester Dairy has since appealed this decision to circuit court, where it remains pending.16

In the second case, citizens groups, individuals, and the Pleasant Lake Management District challenged a high-capacity well permit that the DNR issued to Richfield Dairy, which would house 4,300 cows and 250 steers.17 The DNR permit, as later modified, authorized maximum pumping of 72.5 million gallons per year. The petitioners contended that the DNR’s permit decision failed to consider the cumulative impacts of existing and likely future pumping on water resources in the region, to which the dairy would only contribute. Cumulative impacts typically occur over time, as “gradual intrusions into navigable waters,” even if one project’s effect might seem de minimus.18

In this case, existing pumping had already reduced the nearby Pleasant Lake by approximately two feet, and stream flows by up to 40 percent. The DNR agreed cumulative impacts were not a factor in the agency’s decision to issue the permit, despite urging from science staff that cumulative impacts should be considered.

Yet the DNR contended that it lacked authority to consider cumulative impacts in individual permit decisions. The agency’s chief argument cited the “modified reasonable use doctrine” in State v. Michaels Pipeline, a public-nuisance case filed on behalf of homeowners who experienced property damage and dried wells as a result of dewatering for a sewer pipe installation project.19 The decision rejected the prior rule of nonliability for virtually any use of groundwater, instead holding that withdrawals may trigger liability if they cause unreasonable harm by lowering the water table or reducing artesian pressure. Because the case discussed and recognized liability in terms of substantial harm caused by an individual water user, the DNR argued it could not deny a permit based on harm caused by multiple other water users.

As high-capacity wells proliferate in Wisconsin, water in groundwater-fed streams and lakes is being diverted to these wells beneath the surface, reducing surface-water levels and stream flows.

After a nearly two-week contested-case hearing, the ALJ rejected this argument. As a matter of fact, the ALJ found “[i]t is scientifically unsupported, and impossible as a practical matter, to manage water resources if cumulative impacts are not considered.” That is, “when assessing impacts to a resource, one must examine how existing and proposed impacts affect the resource as a whole from a pre-pumping or pre-impacted condition.”20 The decision additionally recognized that the Richfield Dairy wells, when combined with pumping from other wells, would exacerbate existing reductions in nearby lakes, streams, and wetlands.

As a matter of law, the ALJ determined the DNR “took an unreasonably limited view of its authority to regulate high-capacity well permit applications.”21 In doing so, he relied on statutes, the Lake Beulah case, and longstanding public-trust-doctrine case law that recognized cumulative impacts in permitting decisions: “the Lake Beulah decision has clearly mandated consideration of all available ‘concrete, scientific evidence,’ which has for decades included consideration of cumulative impacts.”22 Because the science had demonstrated that cumulative impacts were harming waters of the state, these effects must be considered when permitting Richfield Dairy’s wells.

In the end, the ALJ ordered the DNR to modify the dairy’s high-capacity well permit to reduce maximum pumping to 52.5 million gallons per year. This amount represented the “appropriate balance between the rights of private parties to a reasonable use of waters of the State, and the rights of the public to not experience detrimental impacts to those public waters.”23 No party appealed the decision.

Legislative Action

Legislators have expressed interest in revising Wisconsin’s high-capacity well permitting framework since the Lake Beulah decision.

One change has already occurred, while the Richfield Dairy case was pending. As part of the state’s 2013-15 biennial budget act, the legislature added Wis. Stat. section 281.34(5m), which states: “No person may challenge an approval, or an application for approval, of a high capacity well based on the lack of consideration of the cumulative environmental impacts of that high capacity well together with existing wells.”24 This change is effective for well-permit applications on or after July 1, 2014, the budget act’s effective date. The Wisconsin Legislative Council has noted it is possible that this provision may be challenged on constitutional grounds.25

Bills drafted in the 2013-14 legislative session also attempted to tackle high-capacity well permitting. Proposals included limiting DNR permitting authority, exempting or grandfathering existing wells from future regulations, and defining remedies for harmful groundwater withdrawals.26

The topic will likely reemerge in 2015. If it does, a strong guiding point is the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s emphasis on following the science in permitting decisions. Otherwise, there could be an “absurd result where DNR knew a proposed high capacity well would cause harm to waters of the state but had to issue the permit.”27 Legislation should also observe the public trust doctrine and cases interpreting it, to avoid a constitutional challenge. Finally, legislators can look to neighboring states for their approaches to groundwater and cumulative impacts, such as established mechanisms in Michigan and Minnesota for permitting new wells and restoring already-affected waters.

Conclusion

Recent legal developments have provided Wisconsin’s groundwater, and the surface waters that depend on it, protection from the increasing effects of well pumping and other stressors. While both legal and resource conflicts may continue in the near future, recent precedent may help create a framework for resolving these conflicts legislatively, administratively, or through future court decisions.

Endnotes

1 Gillen v. City of Neenah, 219 Wis. 2d 806, ¶ 23, 580 N.W.2d 628 (1998).

2 2011 WI 54, 335 Wis. 2d 42, 799 N.W.2d 73.

3 Wis. Stat. § 281.11.

4 Wis. Stat. § 281.34.

5 See Wis. Stat. §§ 281.343, 281.35.

6 Graphic from the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism Project: Groundwater supply. Used with permission of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

7 Wis. Admin. Code chs. NR 812, 815.

8 2011 WI 54, ¶ 4, 335 Wis. 2d 42.

9 See Wisconsin DNR, High Capacity Well Information (last revised May 7, 2015).

10 Wisconsin DNR, Recent high capacity well applications (last updated May 28, 2015).

11 Wisconsin DNR, Wisconsin Water Use, 2013 Expanded Withdrawal Summary (hereinafter DNR 2013 Report).

12 George J. Kraft & David J. Mechanich, Groundwater pumping effects on groundwater levels, lake levels, and streamflows in the Wisconsin Central Sands (2010).

13 Graphic from DNR 2013 Report and used with permission of the Wisconsin DNR.

14 In re Conditional High Capacity Well Approval for Two Potable Wells to be Located in the Town of New Chester, Adams County Issued to New Chester Dairy, Inc. & Milk Source Holdings LLC, Wis. Division of Hearings & Appeals, No. DNR-13-011, Order (Sept. 18, 2014).

15 Id.

16 New Chester Dairy LLC v. DNR, No. 14-CV-1055 (Outagamie Circuit Ct.).

17 In re Conditional High Capacity Well Approval for Two Potable Wells to be Located in the Town of Richfield, Adams County Issued to Milk Source Holdings LLC, Wis. Division of Hearings Appeals, Nos. IH-12-03, IH-12-05, DNR-13-021, DNR-13-027, Order (Sept. 3, 2014), available at www.doa.state.wi.us/documents/dha/Decisions/DNR/2014/dnr13021.pdf (hereinafter In re Richfield Dairy). The author represented Friends of the Central Sands and other petitioners challenging the permit.

18 Sterlingworth Condominium Ass’n Inc. v. DNR, 205 Wis. 2d 710, 729, 556 N.W.2d 791 (Ct. App. 1996).

19 63 Wis. 2d 278, 217 N.W.2d 399 (1974).

20 In re Richfield Dairy, supra note 17.

21 E.g., Hixon v. PSC, 32 Wis. 2d 608, 146 N.W.2d 577 (1966).

22 In re Richfield Dairy, supra note 17.

23 Id.

24 2013 Wis. Act 20, § 2092g.

25 Wis. Legis. Council Information Memo., The Permitting of Groundwater Withdrawals from High Capacity Wells in Wisconsin, IM-2014-05 (Oct. 27, 2014).

26 E.g., 2013 Senate Bill 302.

27 Lake Beulah, 2011 WI 54, ¶ 28, 335 Wis. 2d 42.