In the March 2022 issue of Wisconsin Lawyer,1 I explored on an introductory level the dynamics of technology (algorithms, algorithmic decision-making, machine learning) and human choice (nudges, impacts upon U.S. and global societies). How can these areas be harmonized? Can their distinct and divergent interests reach accommodation?2 In this article I delve into these topics with more detail, especially around personal freedoms enshrined in the U.S. and state constitutions. While the federal Bill of Rights (and state counterparts) has been paramount since the founding of our constitutional republic, it must also be recognized that in a nation of approximately 333 million people,3 there must be significant concern for the public welfare. This delicate balancing act between personal freedoms and the public welfare has been present since the founding of the United States and a considered approach to this balancing is even more important given the continual technological onslaught.4

This article contains a brief refresher of the March Wisconsin Lawyer article; a discussion of technology-related effects on the U.S. Bill of Rights and recent American Bar Association (ABA) activities in the technology and privacy realm; a case study of the issue of “smart cities” and how they illustrate the discussion of technology, democracy, and governance; and a description of a future governed by a new reality – which is essentially a call to action. These sections provide additional depth to lawyers and nonlawyers alike.5

The March 2022 Article: A Refresher

The March 2022 piece introduced the essential concepts of algorithms, algorithmic decision-making, algorithmic regulation, and nudges; discussed how algorithms are now central to politics, economics,6 and social interactions; and discussed 1) the concepts of consent and choice and how they are embedded into U.S. (and western) constitutional and democratic frameworks; 2) the importance of these constitutional and technological concepts to general public education (the latter crucial so that people know that perhaps their “free” choice is not as absolutely free as they thought);7 and 3) what the future holds for this intersection between science, technology, and free choice and consent.

James Casey, Dayton 1988, is a data protection attorney and research manager based in San Antonio, Texas. He recently completed serving as interim associate vice president, research and sponsored programs, and interim director, Emergent Technologies Institute, at Florida Gulf Coast University. He is a founding adjunct associate professor in the CUNY M.S. in Research Administration and Compliance Program. He represents the State Bar of Wisconsin in the ABA House of Delegates, as vice chair of the ABA e-Privacy Law Committee, and is an ABA representative to the National Conference of Lawyers and Scientists (a standing committee of the ABA and AAAS). He is a certified privacy practitioner for the EU GDPR data protection officer role. He is a past president of the State Bar of Wisconsin Nonresident Lawyers Division, a former member of the State Bar of Wisconsin Board of Governors, a Life Fellow of the Wisconsin Law Foundation, and a Patron Fellow of the American Bar Foundation.

James Casey, Dayton 1988, is a data protection attorney and research manager based in San Antonio, Texas. He recently completed serving as interim associate vice president, research and sponsored programs, and interim director, Emergent Technologies Institute, at Florida Gulf Coast University. He is a founding adjunct associate professor in the CUNY M.S. in Research Administration and Compliance Program. He represents the State Bar of Wisconsin in the ABA House of Delegates, as vice chair of the ABA e-Privacy Law Committee, and is an ABA representative to the National Conference of Lawyers and Scientists (a standing committee of the ABA and AAAS). He is a certified privacy practitioner for the EU GDPR data protection officer role. He is a past president of the State Bar of Wisconsin Nonresident Lawyers Division, a former member of the State Bar of Wisconsin Board of Governors, a Life Fellow of the Wisconsin Law Foundation, and a Patron Fellow of the American Bar Foundation.

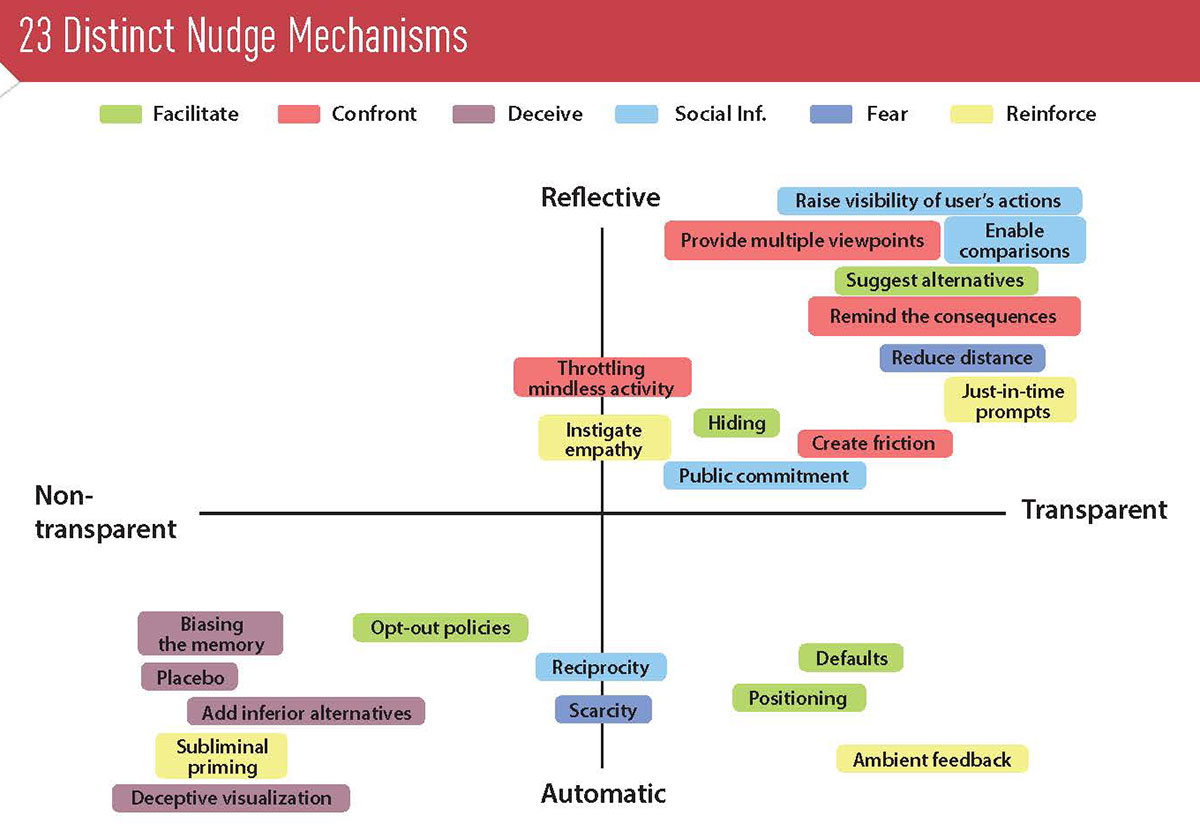

Since the March publication and the writing of this piece, I have had an opportunity to reflect and consider the various issues raised at the intersection of technology, law, and choice and consent. Thus, I briefly revisit and include here the “23 Distinct Nudge Mechanisms” graphic found in the March piece. This graphic provides profound differentiations in the concept of nudges. The graphic shows nudges in four quadrants: two based on mode of thinking engaged (automatic versus reflective) and two based on transparency of the nudge (if the user can perceive the intentions and means behind the nudge).

The graphic presents the 23 mechanisms of nudging, clustered into six categories: facilitate, confront, deceive, social influence, fear, and reinforce.8 Examining the four quadrants, one sees that the upper right (transparent and reflective) and lower left (nontransparent and automatic) are the two most populated quadrants. The lower-left quadrant is least compatible with the concepts of choice, consent, and democracy. Among fair-minded people, who would think that automatic and nontransparent nudges best further the concepts of choice, consent, and democracy? Among the nudges in the lower-left quadrant, subliminal priming best illustrates the significant concerns that algorithms represent in affecting real life. For me, subliminal priming exactly represents what nudging is all about.

Looking at current trends in global governance and societal relationships, it seems that more transparency, not less, is required. And absolute transparency, subject to privacy and national-defense exceptions, best furthers the highest goals of the U.S. and state constitutions.9

New Technologies and the U.S. Bill of Rights

A vital question when discussing issues at the intersection of law and technology is the following: How do emerging technologies impact existing statutes, regulations, and case law? Technologies tend to leapfrog legal doctrine and statutes – the law is most often playing catch up with emerging technologies. Given that the Bill of Rights in the U.S. Constitution – the first 10 amendments governing individual rights – is a significant guiding document to this day, it is crucial that lawyers, legal theorists, and members of the public consider, in their own capacities, how these technologies (in this case, algorithms, machine learning, and so on) impact their most basic and personal rights.

Looking at the amendments in the Bill of Rights, one can see that algorithms, algorithmic decision-making, and machine learning may directly affect the First (freedom of religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition), Fourth (freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures), Fifth (due process of law, freedom from self-incrimination, double jeopardy), Sixth (right to a speedy and public trial), and Eighth (freedom from excessive bail, cruel and unusual punishments) Amendments. This entire listing might not be entirely relevant or accurate now but could be in the future, depending on the development of technologies. Thus, this is all subject to change depending on what the future holds. And this discussion holds true for the similar individual rights enshrined in state constitutions.

While much more may be written on the impact of these recent technologies on these amendments, for space reasons it is best to focus on the Fourth Amendment given the explosion of “big data” and data collection by governmental entities and private actors.10

As written here and in the March piece, American conceptions of consent, choice, and democracy are fundamentally supported by individual rights. Our history has not been perfect, and a just society has been delayed for people in disadvantaged groups. Although many mistakes have been corrected, more needs to be done. So, for example, in protecting the right of individuals to not be subject to unreasonable searches and seizures, we must remain vigilant that innovative technologies do not erode this fundamental constitutional protection. The implementation of recent technologies must be fair, accurate, and transparent in implementation beyond the well-intentioned motives underlying these technologies. This is the challenge for the future. While much is expected of these modern technologies (and indeed ones that have not been created yet), vigilance must be exercised to ensure that they do not erode the regard for humanity found in the individual amendments in the Bill of Rights.

Recent ABA Activities in the Technology Realm

Proposed ABA Resolution 700.In the March article, I mentioned the impact of algorithms in criminal court proceedings.11 At its Feb. 14, 2022, mid-year meeting, the ABA House of Delegates (HOD) considered and passed, as amended, Resolution 700, which deals with a related topic.12 Resolution 700 urges governmental entities to refrain from using pretrial risk assessment tools13 unless the data supporting the assessment are transparent, publicly disclosed, and unbiased (whether explicit or implicit).14 As Stephen A. Saltzburg, introducing the resolution on behalf of the Criminal Justice Section, noted: “The problem is the mathematical models; the risk assessments are only as good as the data that goes into them …. This resolution recognizes that these pretrial assessments can be dangerous, although well intentioned.”15

Embedded in the Resolution 700 Report are the same concepts alluded to in the March article:16

Algorithmic methodology must be public and easily identifiable.

Data used in pretrial assessment tools must be public, objective, easily understood, and free from bias.

Pretrial assessment tools must be subject to studies to ensure their continued validity.

A balance is required between the benefits of a more accurate algorithmic-based model (as opposed to a 100% human model) and the costs and risks of bias, discrimination, and lack of transparency to the public in such a mathematical tool. This is where the benefits of science, mathematics, and engineering can be mobilized to ensure the use of algorithmic tools that assist the criminal justice system while they protect the rights of defendants. The criminal justice system must be just, and citizens must demand this result.

Proposed ABA Resolution 704. The HOD also considered Resolution 704 at its mid-year meeting. Resolution 704 called for the HOD to approve the Uniform Personal Data Protection Act (UPDPA) as promulgated by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (known also as the Uniform Law Commission (ULC)). As it has done with uniform laws on a variety of topics, by passing the UPDPA the ULC indicated that it considers the act to be appropriate for states desiring to adopt the specific substantive law therein.17

Resolution 704 ended up being withdrawn but it likely will be reintroduced at the ABA HOD Annual Meeting in August 2022.18

The ABA Science & Technology Law Section (SciTech) took a significant role in opposing Resolution 704 as written, noting that the act tips the balance of power toward businesses and away from individuals. The ULC’s support of the resolution reflects a top priority of the ULC: to lower compliance costs for businesses. Among the general concerns identified by a SciTech working group are strong opposition from consumer groups; controversial, harmful, or problematic provisions; and that key provisions are inconsistent with the Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs). FIPPs are fundamental to privacy laws today. The eight principles (transparency, individual participation, purpose specification, data minimization, use limitation, data quality and integrity, security, and accountability and auditing) are found in the legislation of the Privacy Act of 1974.19

In my comments to the SciTech working group, I noted that individual consent has been watered down, reliance on state attorneys general for enforcement is not sufficient, and an omnibus federal privacy statute is needed to protect data privacy as a human right and not as a business accommodation. Individual consent is a principal component of privacy as a human right, and individual privacy rights should not depend on business accommodation. A real-world example bringing together the areas of algorithms, human choice, government management, and constitutional protections is the issue of “smart cities,” discussed below.

Smart Cities

What are smart cities? One such definition and the corresponding characteristics is the following:20

“A smart city uses information and communication technology (ICT) to improve operational efficiency, share information with the public and provide a better quality of government service and citizen welfare.”

The main goal of a smart city is to optimize city functions and promote economic growth while improving the quality of life for residents by using smart technologies and data analysis. The value lies in how this technology is used rather than merely how much technology is available.

A city’s “smartness” is determined using a set of characteristics, including the following:

An infrastructure based around technology;

Environmental initiatives;

Effective and highly functional public transportation;

Confident and progressive city plans; and

People able to live and work within the city, using its resources.

The success of a smart city relies on the relationship between the public and private sectors because much of the work to create and maintain a data-driven environment falls outside the local-government function. For example, smart surveillance cameras may need input and technology from several companies.

Aside from the technology used by a smart city, there is also the need for data analysts to assess the information provided by the smart-city systems so that problems can be addressed and improvements can be found.

As the infusion of technology makes cities “smarter,” these jurisdictions will be collecting large amounts of data – some anonymous but some that is personal identifiable information (PII).21 Coupled with the ongoing pandemic (and the collection of large amounts of health data-PHI),22 it is easy to see the intersection of topics discussed in this article and the March piece.

The collection of data in smart cities leads to a specific concern about protection of individual privacy under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and its protection against unreasonable searches and seizures by government actors. As noted above, the Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable searches and seizures by governmental actors is the primary Bill of Rights concern regarding loss of individual privacy posed by technological tools such as algorithms.

The Future as Dictated by a New Reality

While I was writing about algorithms, nudges, and individual rights, the global community was battling the COVID-19 virus. Now there is another very significant issue on the global stage – the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine. The latter is inflicting untold pain and suffering on the people of Ukraine and threatens to spill beyond its borders. Economic and political systems carefully constructed and promoted since 1945 have been affected in ways not yet fully understood. The use of emerging technologies – using constantly developing algorithmic and machine-learning techniques – to fight the war in Ukraine and the pandemic means that the global stage will not become stable for some time to come. Are people ready for another prolonged period of uncertainty?

What does our global situation have to do with the topics of algorithms, machine learning, and human choice? Everything. I offer the following possibilities, not fixed predictions.

Increased reliance on algorithms and algorithmic decision-making. One likely result of the war in Ukraine will be an increased reliance on algorithms and algorithmic decision-making. War has the unfortunate (but sometimes necessary) tendency to speed the development of military tools and weapons, and some of those technologies later enter the civilian economy. These are some of the unintended consequences of war. The same is true regarding medical breakthroughs that have emerged in the fight against the COVID-19 virus, or scientific-engineering breakthroughs from the Mercury and Apollo space programs.

Continual integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning into the weapons of war. A second, and parallel observation, is that artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning will continue to be integrated into weapons of war. This was going to happen regardless, but I foresee a faster integration. One theme in the March article was that AI and machine learning should assist humans in making better decisions, not replace human decision-making.

Redoubling of efforts to maximize the humanity of technology. Lastly, I think there must be an emphasis on efforts to maximize the humanity of technology. I am reminded of this while watching the high-tech weapons of war being used against the Ukrainian people and seeing the destruction, misery, and displacement that these weapons are causing. While a theater of war is always different than a more peaceful, domestic scenario, present circumstances should remind us that there are downsides to the unquestioned use of high-technology tools.

Conclusion

Perhaps the future is so bright that we will need to wear shades, after all.23

Continual rapid technological developments, such as algorithms and machine learning, and challenging social-political-cultural realities, mean that the future is cloudier than in recent memory. What does this mean for the tech titans, political leaders, and other stakeholders in the social-political-cultural realms? Sometimes when the future is cloudy the best course of action is to go back to the basics of transparency, integrity, and humanity. Perhaps this is the direction in which we should go.

Endnotes

1 James Casey, Nudges, Algorithms, and Human Choice: What Does the Future Hold? 95 Wis. Law. 24 (March 2022), www.wisbar.org/NewsPublications/WisconsinLawyer/Pages/Article.aspx?Volume=95&Issue=3&ArticleID=28962.

2 In April 2022, the author was interviewed by Matthew F. Knouff, CIPP/US, CEDS, RCSP, a New York-licensed attorney. The interview is on his YouTube channel titled ESI (Electronically Stored Information) Survival, at www.youtube.com/channel/UCMVdtcqBLd1EXyHrP4Dc9kg.

3 www.census.gov/popclock/.

4 California is creating the first online privacy regulator in the United States, to regulate the activities of Facebook, Google, Amazon, and other companies. Known as the California Privacy Protection Agency and charged with enforcing that state’s privacy law, it will be staffed with more than 30 people and have a budget of approximately $10 million. David McCabe, How California Is Building the Nation’s First Privacy Police,www.nytimes.com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.nytimes.com/2022/03/15/technology/california-privacy-agency-ccpa-gdpr.amp.html.

5 Some people believe the future of healthy eating lies in artificial intelligence. See, e.g., Sandeep Ravindran, Here Come the Artificial Intelligence Nutritionists (March 14, 2022), www.nytimes.com/2022/03/14/well/eat/ai-diet-personalized.html.

6 For some excellent commentary pertaining to ethics, data, and privacy by design in the advertising space, see recent comments of Matt Brittin, president of Google EMEA, at https://blog-google.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/blog.google/technology/safety-security/matt-brittin-data-ethics-and-privacy-design/amp/.

7 As explained by Athens, Greece-based attorney Matina Kresta: The ancient Athenians placed a higher value on education and culture and believed that educated people made the best citizens. Children were educated to produce good citizens and advance their society as they became adults. LinkedIn post from Matina Kresta to Author, April 3, 2022. See also the discussion of the dialogue Protagoras by Plato, especially as it pertains to the linkage between education and the citizenry, www.sparknotes.com/philosophy/protagoras/themes/;https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/protagoras/.

8 See also Ana Caraban et al., 23 Ways to Nudge: A Review of Technology-Mediated Nudging in Human-Computer Interaction (May 2019), www.researchgate.net/publication/332745321_23_Ways_to_Nudge_A_Review_of_Technology-Mediated_Nudging_in_Human-Computer_Interaction.

9 For an excellent article on the new rules in data privacy, see https://hbr.org/2022/02/the-new-rules-of-data-privacy. (For some readers, this article will be behind a paywall.)

10 The Winter 2022 issue of The SciTech Lawyer covers various dimensions of this interface between technologies, law, and government management in the “smart cities” context. Topics such as mobility and the autonomous vehicle, an equitable technological future, the connection to the pandemic, impacts upon the sports industry, Fourth Amendment protections (which are covered elsewhere in this article), and the philosophical yet operational question of whether people should or can hide in a “smart community” are covered and accessible here: www.americanbar.org/groups/science_technology/publications/scitech_lawyer/2022/winter/.

Like any area of the law dealing with emerging technologies, material in this specific issue may be changing in the coming months and years or may become obsolete if a great leap forward is made in technology.

11 For an excellent introduction into this exploding area of criminal justice, see Alex Cholas Wood, Understanding Risk Assessment Instruments in Criminal Justice (June 19, 2020), www.brookings.edu/research/understanding-risk-assessment-instruments-in-criminal-justice/.

12 www.abajournal.com/news/article/resolution-700.

13 Northpointe is one such suite of risk assessments in criminal proceedings. Seewww.equivant.com/northpointe-risk-need-assessments/.

14 www.abajournal.com/news/article/resolution-700.

15 Id.

16 Id.

17 www.americanbar.org/news/reporter_resources/midyear-meeting-2022/house-of-delegates-resolutions/; www.americanbar.org/news/reporter_resources/midyear-meeting-2022/house-of-delegates-resolutions/704/.

18 www.americanbar.org/news/reporter_resources/midyear-meeting-2022/house-of-delegates-resolutions/704/.

19 Dep’t of Homeland Sec., The Fair Information Practice Principles, www.dhs.gov/publication/privacy-policy-guidance-memorandum-2008-01-fair-information-practice-principles (last updated Nov. 12, 2021).

20 www.twi-global.com/technical-knowledge/faqs/what-is-a-smart-city;https://smartcitiesconnect.org/what-a-smart-city-is-and-is-not/.

21 See the U.S. Department of Labor website for an excellent discussion of what PII is and why and how it must be protected. U.S. Dep’t of Lab., Guidance on the Protection of Personal Identifiable Information, www.dol.gov/general/ppii (last visited April 12, 2022).

22 Personal health information is a type of personal information that has specific meaning, use, and protection under U.S. law. Seewww.hhs.gov/answers/hipaa/what-is-phi/index.html.

23 See “The Future’s So Bright, I Gotta Wear Shades,” a 1986 top 20 Billboard Hot 100 hit by Timbuk 3. A pessimistic look at the future during the Reagan years, www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qrriKcwvlY.

» Cite this article: 95 Wis. Law. 38-43 (May 2022).