Johanna Kirk, Kirk Law Office LLC, Superior,

is busy in her practice, which allows her to pick

and choose clients and matters. She uses practice

management software and other technology to reduce

time spent on administrative and business development

tasks, such as client invoicing and marketing, and

spend more time on actual lawyering.

Superior solo attorney Johanna Kirk is doing well. She’s busy in her estate, probate, and business law practice, Kirk Law Office LLC. She can pick and choose clients and matters. She bills most matters as fixed-fee arrangements, which her clients love. And practice management software and other technology allows her to reduce time spent on administrative and business development tasks, such as client invoicing and marketing.

“I probably spend about an hour to an hour-and-a-half on administrative tasks, and up to 45 minutes on marketing or business development,” said Kirk, who opened her law firm in 2013. “I spend about two hours per day on those types of administrative tasks.”

Kirk knows this information because she tracks her time through practice management software, which can generate reports about her billable and nonbillable activity.

And even though Kirk bills almost all matters on a fixed fee, the software allows her to understand the value of a fixed-fee project, considering overhead costs and profit margins, and it creates efficiencies that let her spend more time on actual lawyering.

Kirk uses technology to leverage her time. But she may be an outlier. The State Bar of Wisconsin’s 2017 Economics of Law Practice Survey Report (EOP report) indicates only 54 percent of solo attorneys track all their time. Twenty-two percent say they only track billable hours. But that isn’t even the most surprising statistic.

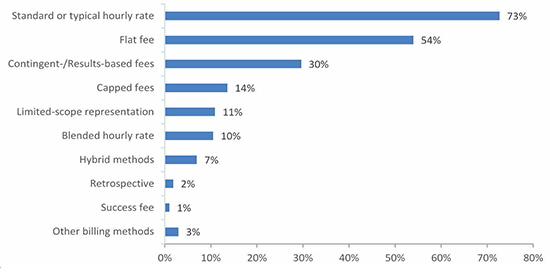

Use of Billing Methods and Standard Hourly Rates – Private Practice

Are You Wasting Time?

The EOP report indicates that lawyers work, on average, 46 hours per week. But only 25 hours are spent on billable work. More than 14 hours per week go to nonbillable activity, and those numbers might paint a “rosy” picture of what’s actually happening.

Clio, a law practice management software platform with more than 150,000 users in multiple countries, aggregated data from 60,000 users and conducted a survey of nearly 3,000 legal professionals to help generate its 2017 Legal Trends Report. It says the average lawyer “utilizes” 2.3 hours per day on “billable work,” and collects on even less.

Joe Forward, Saint Louis Univ. School of Law 2010, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6161.

Joe Forward, Saint Louis Univ. School of Law 2010, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6161.

“Most surveys tend to align people at around a 60 percent utilization rate,” said Joshua Lenon, the lawyer-in-residence at Clio, based in Vancouver, B.C. “In reality, if you look at the billable hours they are running and use a statistical estimate based on the minimum eight-hour work day, you end up with a utilization rate that is much lower.”

Among Clio users in Wisconsin, the utilization rate is 36 percent – lawyers spend 36 percent of an eight-hour day on billable work, which is better than lawyers in most states. The data indicate that lawyers are either not busy enough, or not efficient.

In the EOP report, however, only 26 percent of private lawyers reported that they are underworked. The rest said they are at full capacity (57%) or overloaded (18%).

Lenon says Clio’s data should indicate a breakdown in law firm efficiency. He encourages lawyers to track all of their time, including billable and nonbillable activity.

In turn, the data will help law firms understand where billable time is lost and what processes or technologies they can implement to improve efficiency.

Tom Palzewicz, managing partner and certified business coach at ActionCoach in Elm Grove, agrees that lawyers can do more to increase profitability. They should be looking at technology solutions or delegating nonbillable work to nonlawyer staff, he says.

“It’s simple. If you want to maximize billable hours, you have to stop doing nonbillable work,” he said. “One of the biggest obstacles for professional services, and not just lawyers, is building a business when profit is tied to your time in providing the service.”

The Economics of Law Practice for Corporate Counsel – Doing More With Less Outside Help

Full-time in-house counsel attorneys earned a median salary of $140,000 in 2016, compared with $96,000 for private practitioners. And only 10 percent say their workload is less than they can handle, compared to 26 percent for private practitioners.

Corporate counsel attorneys work an average of 47 hours per week, similar to private practitioners, but more in-house counsel reported being overloaded than did private practitioners.

Sixty-six percent of in-house attorneys said their workload increased in 2014 and 2015, and 52 percent estimated that their workload would again increase in 2017 and 2018.

About 56 percent of in-house counsel spent time on contracts in 2016, 50 percent on regulation and compliance, and 39 percent on labor and employment issues.

“Doing more with less is always among the conversation,” said Nicole Willette, in-house counsel for Franklin Energies, based in Port Washington. She’s also the president of the Association for Corporate Counsel (ACC), Wisconsin Chapter.

“I’ve heard people talking [at ACC events] about having overflow resources available when a legal department gets backed up and building those relationships,” she said.

“I have also heard other corporate counsel talking about trying to be innovative and put in different fee structures with outside counsel,” she said. “But people also talk about the importance of finding the right attorney to handle the work.”

The EOP report reveals that 77 percent of corporate counsel outsourced litigation in 2016, followed by regulatory, compliance, and governance (52%), employment and human resources (49%), and intellectual and patent issues (48%). On average, corporate counsel spent a median of $150,000 on outside counsel in 2016.

Willette is the sole in-house attorney for Franklin Energies, a company with 30 offices and more than 1,000 employees. She said her role expanded quickly after joining the company in 2012 – the more work she turns around, the more she gets – but she looks to outside counsel to help on litigation issues or issues outside her expertise.

“We have a firm we are comfortable with and can handle most of our issues,” said Willette. “If it’s a matter in a different state, I ask for referrals from connections or people that I trust to figure out who is the right person to handle that work.”

About the Survey

The “utilization rate” in Wisconsin is just one data point within the 2017 Economics of Law Practice Survey Report, a distillation of law practice information collected in 2016.

The survey sample was stratified into four practice settings (based on trust account designations): private practice, corporate counsel, government/academic, and “other.” The private practice group was further stratified by geographic region and office size.

A total of 1,220 State Bar members returned usable questionnaires, including 706 from private practitioners, 124 from corporate counsels, 271 from attorneys in government, public service, or academic settings, and 119 from attorneys in the “other” category.

Sixty-two percent of respondents were men, and 38 percent were women. That ratio is representative of the current State Bar membership as a whole, with 65 percent men and 35 percent women. But the sample is also reflective of the closing gender gap.

For instance, nearly half of all respondents under age 40 were women. For the membership as a whole, about 45 percent of all Wisconsin lawyers under age 40 are women. The gender gap widens for older age groups, especially in private practice.

The State Bar’s Economics of Law Practice Survey Report, last released in 2013, provides a snapshot of law practice economics across practice settings in Wisconsin.

Lawyers, law firms, and legal departments can use the information to assess their own practices, evaluate what competitors may be doing, and make better decisions about where to find efficiencies and allocate resources for better practice management.

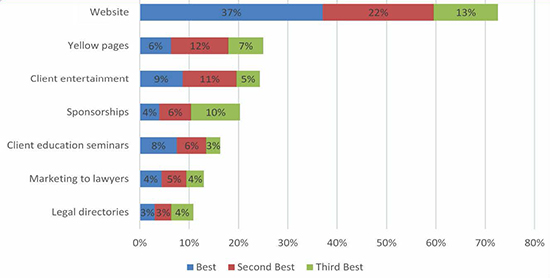

Top Marketing or Advertising Vehicles That Produced the Best Results – Private Practice

Hourly Rates and Flat Fees

It appears the hourly rate is still the most common billing method among private practitioners in Wisconsin. Of those surveyed, 73 percent still use the billable hour. Fifty-four percent of those surveyed use flat fees, and 30 percent use contingent fees.

The typical hourly rate increased by almost nine percent from 2013, to $251 per hour among private practitioners responding. But the EOP report also identifies average billing rates by law firm size, years in practice, region, gender, and position title.

For instance, the average billing rate among solo practitioners is $211 per hour. Attorneys in offices with two to five attorneys charge an average of $237 per hour.

New lawyers (0 – 2 years in practice) bill at $150 per hour, while lawyers with 11 – 15 years of experience bill an average of $236 per hour. The average billing rate among male respondents was $265 per hour, versus $223 per hour among women lawyers.

Emery Harlan, MWH Law Group LLP, Milwaukee, runs a tight ship, thanks to some hard firm-management lessons learned at a

former firm. His current firm’s decision-making about overhead expenses is much more intentional, and thus expenses are well

controlled and predictable, allowing for a very profitable practice. Photo: Kevin Harnack

Associates average an hourly rate of $206 per hour, compared with $239 per hour for senior associates and $295 per hour for equity partners or shareholders.

Of those charging flat fees, most are doing so in the estate planning area, which is the top practice area in Wisconsin. For instance, 37 percent of respondents draft simple wills, and 73 percent of those lawyers charge a median flat rate of $230 for that service.

At $230, how do Wisconsin estate planners compete with online legal service providers such as LegalZoom, which offer simple wills starting at $69? By explaining the value of attorneys, says Tom Burton, who runs a virtual law office in Chippewa Falls.

“If they want to go through LegalZoom, they have already looked at the website and decided if it's the right fit for them,” said Burton, who offers estate planning, business, and real estate services in Wisconsin and Minnesota. “But by the time the client gets to the point of meeting with me, I think they see the value in hiring an attorney.

“You need to ask the right questions to know how to draft a client's will or estate plan,” he said. “After discussing it with me, they usually realize it is not as 'simple' as they may have thought and they also see the value in the advice I am providing.”

The Economics of Law Practice for Government Lawyers – Increased Workloads, No Similar Pay Boost

Government lawyers and lawyers working in academic settings earn a median gross income of $86,000 per year. Based on years in practice, government attorneys do not progress the same as private practitioner and corporate counsel counterparts.

For instance, a new lawyer (0-2 years in practice) makes a median income of $49,000, compared to $52,000 for private practitioners and $72,200 for in-house counsel.

But government lawyers with 16 – 25 years of experience make a median salary of $103,000 per year, compared to $147,000 for private lawyers and $179,000 for in-house counsel.

Government attorneys reported working, on average, 45 hours per week. But 38 percent of government lawyers reported work overload, the highest proportion of all attorneys.

“Salary and workload continue to be challenges for many government lawyers,” said Mary Schanning, assistant city attorney for Milwaukee and the president of the State Bar Government Lawyers Division. “Governments are trying to do more with less, which means increased workloads for government lawyers without a similar increase in pay.”

“District attorneys and public defenders seem to be particularly affected by this trend,” she said. “It is becoming more difficult for attorneys to see government work as a long-term career choice because of the relatively low wages compared to the private sector, particularly when faced with challenges of paying law school debt and raising a family.”

Collection Rates

Although the report indicates higher hourly rates since 2013, that does not mean lawyers have the same “realization” rate per attorney. Some attorneys may write-off time or discount services. The EOP report indicates an average of five hours per week as “unbilled legal work and research.” At $251 per hour, that’s $1,255 of free legal work.

“This is very common. They actually write-off some of the billables before even sending the bill,” Palzewicz said. “It cuts into their margin. Then they have problems collecting, which cuts into their cash flow. Most attorneys probably undervalue their services.”

In addition, all practitioners report an average of 6.8 percent of fees are deemed “uncollectible.” That uncollectible rate is higher for attorneys in firms with fewer than five attorneys, and rises to eight percent or higher for attorneys in the rural north.

One of the problems, Lenon says, is that lawyers may limit payment options, or send invoices when clients have less incentive to timely pay the bill.

Mary Schanning, assistant city attorney, Milwaukee, says

salary and workload continue to be challenges for many

government lawyers. Governments are trying to do more

with less, which means increased workloads for government

lawyers without a similar increase in pay. One result is it’s

becoming more difficult for lawyers to see government work

as a long-term career choice as compared to private practice.

For instance, do you have a process that allows clients to pay online by credit card? Do you request payment when the month ends, or when the matter closes? “By limiting collection methods, lawyers are not able to strike while the iron is hot,” Lenon said.

“When a client closes a matter with a lawyer, that’s the moment to get the client to pay the bill. If they are not using modern collection techniques, they are actually making it more likely that they won’t get paid with every extra step in the process,” Lenon said.

Clio, for instance, has integrated credit card processing. A client receives a bill as an email, and a link directs them to pay it right away. Lenon says modern collection methods help lawyers increase collection rates and reduce time spent on collections.

It’s also what clients want. Clio surveyed about 2,000 consumers and the vast majority said they want a lawyer who will respond to them quickly and offer free consultations.

“After that, you can see the breakdown on a variety of different features that they really wanted from a lawyer, most of which were related to communication and ease of service, such as paying a bill by credit card,” Lenon said. “People don’t pay bills by check anymore. So, lawyers should be giving clients a modern means to pay.”

Median Hours Engaged in Work-Related Activities – Private Practice

Typical Hours Per Week: |

Median |

Billable Legal Work |

|

Hourly rate |

25.0 |

Fixed/flat rate |

10.0 |

Contingency fee |

10.0 |

Other billing method |

5.0 |

Office administration |

5.0 |

Marketing/public relations |

2.5 |

Unbilled legal work and research |

5.0 |

Other non-legal aspects of practice |

3.0 |

Employment other than law practice |

5.0 |

Total Hours in a Typical Week |

47.0 |

Approximate Hours in 2016: |

|

Continuing legal education (CLE) |

20.0 |

Pro bono services for which you were not compensated |

25.0 |

Median Hours Engaged in Work-Related Activities –

Corporate Counsel/In-House and Government/Academic Attorneys

Typical Hours Per Week: |

Corporate/ In-House |

Government/ Academic |

Legal work |

40.0 |

40.0 |

Office administration |

5.0 |

5.0 |

Marketing, public relations |

2.0 |

N/A |

Training and development |

2.0 |

2.0 |

Other aspects of your job |

5.0 |

5.0 |

Uncompensated legal work and research |

4.0 |

5.0 |

Legal work – compensated outside of job |

5.0 |

5.5 |

Legal work – not compensated outside of job |

9.5 |

10.0 |

Total Hours in a Typical Week |

47.0 |

45.0 |

Approximate Hours in 2016: |

|

|

Continuing legal education (CLE) |

20.0 |

20.0 |

Pro bono services for which you were not compensated |

15.0 |

20.0 |

Overhead Rates

Emery Harlan had an interesting year in 2016. The firm he co-founded, Gonzalez, Saggio & Harlan LLP – one of Milwaukee’s largest minority-owned businesses with 15 offices across the country and more than 100 attorneys – closed its doors.

A day later, he and attorney Kerrie Murphy opened MWH Law Group LLP, also a minority-owned law firm, now with 18 attorneys and six nonlawyer staff members.

Harlan said he learned some hard firm-management lessons at his former firm. “We were perhaps not as disciplined as we should have been around overhead and personnel costs,” said Harlan “Now, we are rigorous in making those decisions.

“We are much more intentional about decisions to add headcount,” said Harlan, whose firm focuses on employment litigation but also does personal injury and transactional work. “That has led to us having expenses that are very well controlled and predictable, allowing us to run an extraordinarily profitable practice.”

In other words, Harlan’s firm is running a tight ship. But what does a tight ship look like? How do law firms know when they are spending too much on overhead or personnel? The EOP report provides some clues on average law firm overhead costs.

It shows median overhead expenses in relation to gross income for law firms, based on office size. Overhead expenses include salary and fringe benefits for nonlawyer personnel, office space and equipment, insurance, and other costs.

For instance, the average overhead for a solo attorney is $27,900, which accounts for about 28 percent of the $100,000 median gross revenue for solos. Smaller firms (2-10 attorneys) reported overhead rates between 28 and 30 percent of gross revenue, and firms with more than 10 attorneys had an average overhead rate of 24 percent. Total median overhead expenses for private practitioners were $113,500 in 2016 compared to $102,050 in 2012.

Fewer lawyers are billing clients for travel time and travel expenses, compared to 2013. For instance, about 63 percent reported billing clients for travel time, compared to 71 percent in 2013. Attorneys did not report significant change on other billed expenses.

But law firms did report paying more in salaries for paralegals and administrative assistants. For instance, the average salary for a paralegal with five to nine years of experience is $47,339, but their average billing rate has increased to $118 per hour.

Palzewicz says law firms are often wary of adding staff, but doing so may help lawyers focus on billable work instead of administrative tasks that can eat into billable time.

“Look at where you are spending time,” he said. “Hiring staff can help attorneys be more profitable by delegating administrative and other tasks to focus on higher value work.”

Kirk hired a part-time paralegal in July 2017 and hired her full time in November, and it’s working out. “I absolutely get to focus more of my time on higher value work,” Kirk said. “She’s enabled me to nearly double my client load and the amount of work I can take on without sacrificing any quality or value of the work we are doing.”

Kirk’s paralegal also takes everyday office operations off her plate, such as answering phones, making coffee, and running bank deposits.

“She’s also proven herself invaluable in legal-based activities like drafting initial documents for estate planning clients, helping keep track of forms and deadlines in probate files, drafting pleadings and discovery, managing client communications, helping with overall file management, and monitoring my daily calendar,” Kirk said.

Gender Pay Disparity – Gap Widens with Years in Practice

Men in full-time private practice, on average, make a median gross income that is 23 percent higher than women in full-time private practice. The gender pay gap is less pronounced for the first 10 years of practice, but widens dramatically for attorneys in practice 11 years or more. For instance, men reported median gross incomes between five and 14 percent higher than women attorneys in the first 10 years.

However, the gender pay disparity jumped to 38 percent for attorneys with 11 to 15 years in practice ($130,000 median gross income per year versus $80,000 per year), 19 percent at 16 to 25 years in practice, and 22 percent at 26 or more years in practice.

How does pay disparity in Wisconsin compare nationwide? A 2016 survey of 2,100 law firm partners nationwide revealed a 44 percent pay disparity between men and women. The primary reason? Origination. Men brought in more business, or received the credit for it.1

Pay disparities also exist in the corporate counsel and government/ academic settings, although the gap is not as wide. Male in-house counsel, on average, made seven percent more than women. In government settings, men made 17 percent more.

The Association for Women Lawyers (LAW) Board released a statement regarding the gender pay disparity issue: “We are disappointed to read that there continues to be a gender pay disparity and that there has not been improvement over the last five years. From our perspective, there is no easy answer regarding why such a pay disparity continues to exist, which is why this issue persists and has been hard to rectify. Part of the issue is increasing the visibility of the contributions women have made and continue to make to the legal profession, some of which do not fall within the typical considerations when deciding compensation.

“As an organization, AWL strives to highlight these valuable contributions and bring awareness to the important role that female attorneys have in the legal profession. We are also committed to working with our members to help them develop the skills and network that they need to advance in their careers, and we remain hopeful that as more women who have the skills to advocate for themselves and others are placed in leadership positions in private practice and elsewhere, the gender pay disparity will be a thing of the past.”

1 Elizabeth Olson, A 44% Pay Divide for Female and Male Law Partners, Survey Says, NY Times, Oct. 12, 2016.

Technology and Practice Management

A few months ago, Thomson Reuters published the 2017 State of U.S. Small Law Firms, which came to an interesting conclusion: “despite recognizing the presence of challenges, a large number of small law firms admit they haven’t done much to address those challenges.” Namely, of the lawyers who acknowledged that administrative tasks take up too much of their time, more than 80 percent say they did nothing about it.

State Bar Practice Management Advisor Christopher Shattuck agrees that practice management and technology tools can help lawyers and law firms reduce overhead and increase efficiency. But many lawyers aren’t using them to their advantage.

“Using a patchwork of systems or processes for practice management tasks is inefficient when better tools are available,” Shattuck noted. “When thinking about information technology infrastructure, law firms should be thinking longer term.”

According to the EOP report, only 21 percent of solo practitioners outsource information technology, indicating they have not engaged vendors to help them manage it. Shattuck says lawyers should certainly learn how technology solutions can help them.

“There’s a whole litany of case management software solutions that people can use. And what software they use depends on the data they have,” he said.

Christopher Shattuck, State Bar practice management advisor, Madison, says practice management and technology tools can

help lawyers and law firms reduce overhead and increase efficiency. State Bar members can receive discounts on formal case

management software – tools that offer more comprehensive solutions that can integrate existing systems, applications, and

services into one program. Reach Christopher at cshattuck@wisbar.org.

“Some law firms’ clients may not want them to store information in the cloud, so they could not use any cloud-based practice management systems,” he noted. “Those without that restriction can use cloud-based practice management services, instead of software that only stores data on internal servers, provided the law firm uses reasonable efforts to adequately address potential risks.”

Shattuck said State Bar members can receive discounts on the type of “formal case management software” that Kirk uses in her solo firm in Superior. Such tools offer more comprehensive solutions that can integrate existing systems, applications, and services into one program.

That includes billing, tracking time, managing and assembling documents, organizing contacts and legal matters, and calendaring, to name a few existing features.

“It’s an investment of a few thousand dollars per year,” Shattuck said. “But if lawyers are spending 14 hours per week on tasks that can be automated by software, they can easily recoup that cost by creating more time for billable work.”

Technology will continue to improve a lawyer’s ability to leverage time, he says. Clio, for instance, integrates with a virtual answering service that can answer phones on behalf of a lawyer, take notes on client queries, and calendar deadlines or events.

That is huge for a solo or small firm attorney without an administrative assistant to handle those tasks, because Lenon indicates that distractions are a big problem.

“Our survey shows that most attorneys are interrupted between six and 10 times per day,” said Lenon, noting research that shows it can take, on average, 23 minutes to refocus after an interruption. “Interruptions could be billable work, but more often than not, they appear to be part of that six hours that just kind of disappears from your revenue.

“When we looked at how staffing affects interruptions, just having one staff member to shield the lawyer cut the number of interruptions in half. And it didn’t matter what type of staff member they were: onsite staff, a virtual assistant, or an answering service.”

Median Gross Income by Practice Setting and Gender

|

Private Practice |

Corporate Counsel |

Government/ Academic |

All Attorneys |

$96,000 |

$140,000 |

$86,000 |

Female |

$71,500 |

$132,500 |

$79,000 |

Male |

$105,000 |

$150,000 |

$92,000 |

Top 4 Private Practice Services Offered and Typical Flat Fee Charged

|

Offered |

Flat Fee Charged |

Simple Will |

37% |

$230 |

Power of Attorney |

36% |

$113 |

Deed Preparation |

32% |

$143 |

Directives to Physicians |

28% |

$100 |

Average Private Practice Billing Rates for Associates

Level of Experience |

2012 |

2016 |

None |

$166 |

$175 |

1-4 Years |

$182 |

$195 |

5-9 Years |

$206 |

$225 |

10+ Years |

$234 |

$250 |

Marketing and Advertising

The survey report indicates that fewer lawyers are using the Yellow pages to market their services. Almost half (47%) of respondents indicated using the Yellow pages as an advertising vehicle in 2013, compared to about 35 percent in the 2017 report.

And that’s a good thing, according to Aly Lynch, a law firm consultant at Next Step Legal Consulting LLC. “The Yellow pages should have been dead years ago,” she said. “It’s an outmoded form of marketing with limited use. It’s a waste of money.”

But the Yellow pages are still in the top three for marketing tools. Websites are the top marketing tool, with 64 percent of private practitioners indicating they have a website. Sponsorships are second at 40 percent, with the Yellow pages third at 35 percent.

At the same time, more attorneys are turning to social media tools, such as Twitter, Facebook, and blogs, to market their services. For instance, 28 percent of respondents now use Facebook as an advertising vehicle, compared to 18 percent in 2013.

Lynch said social media tools give firms more business development opportunities and provide new ways to target clients who are searching for legal information online.

“You can really showcase your expertise,” said Lynch. “If you can be in those online spaces and offer something of value to them, they will likely come back to you when they need a lawyer.” And technology can help lawyers seamlessly spread the word.

Kirk, the solo practitioner in Superior, maintains her own website, which includes a blogging tool. “I’ve got it set up so that when I put up a new blog article on my website, it automatically publishes it on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn,” she said.

Clio’s Legal Trends Report provides more insight on why an online presence is highly important for lawyers. About 62 percent of consumers said they get referrals from friends and family, and 37 percent use online search engines.

“People look for attorneys in their networks, just as they always have,” said Lenon. “But those networks are shifting a little bit. You used to ask your neighbor for a referral, but now you ask your Facebook group. After that, they start looking online.”

Lynch said these marketing vehicles also provide business development opportunities for attorneys who may have little time or desire for traditional networking with clients.

“We can’t expect attorneys to be all things anymore. That’s just not the reality and not the best way to use people,” Lynch said. “If someone is a great writer, use them in that capacity. Or maybe you know a theatre major who would be great on law firm videos.”

Full Survey Report Guides Your Practice Management Decisions

For attorneys looking for in-depth information, the full Economics of Practice in Wisconsin: 2017 Survey Report, based on 2016 data, provides the detail needed to get a fuller view of the economic picture of practicing law in Wisconsin. By applying your own data against the survey’s aggregate results, you’ll see how your individual practice compares. The survey report’s straightforward information, charts, and tables can help you make independent decisions to manage your practice more efficiently and effectively. Separate sections cover private practitioners (both solo and in group practices), government/academic attorneys, and corporate attorneys and in-house counsel.

The survey report includes:

- Top areas of practice

- Private practitioner net income, by demographics

- Private practitioner hourly billing rates

- Private practitioner billing methods

- Office expenses and revenues

- Law office support staff salaries

- Work volume for each category (private practice, government/academic, corporate)

- Benefits by employer category

- Billing and timekeeping practices

- Trends in marketing legal services

- Perceptions of the supply and demand for legal services

- Change in workload over past two years and over next two years

- Changes made in billable hours policy

The 2017 survey report is available to State Bar members for $49/print or $39/electronic PDF; and to nonmembers for $79/print and $69/electronic PDF. To order, visit WisBar's Marketplace, or phone the State Bar at (800) 728-7788.

Note: The survey is intended to enhance opportunities for independent competitive decisions. Each attorney must make independent decisions concerning the interpretation and use of this information in the context of the attorney’s specific business.

The Bigger Fish

While some large law firms are expanding through mergers and acquisitions – von Briesen & Roper S.C., which recently acquired the 22-lawyer firm of Peterson, Johnson & Murray S.C., now has 192 lawyers – mid-sized firms in Wisconsin are competing with bigger firms by offering high-level expertise in select practice areas.

And that appears to be the national trend. “Some of the more niche-oriented work is going to mid-sized and smaller firms,” said Oliver Yandle, executive director of the Association of Legal Administrators (ALA), based in Chicago. The ALA has a membership of more than 8,000 law firms, mostly ones with fewer than 100 attorneys.

“They are looking for firms with specialized expertise and a demonstrated ability to deliver those services, not only in an effective manner, but in a way that is more cost effective and responsive to some of the cost pressures they are facing,” he said.

Yandle said successful firms are becoming much more immersed in the business needs of their clients, not in terms of legal work, but what the business is trying to accomplish strategically and how the law firm can help the organization achieve those goals.

“Having that trusted business advisor perspective to help their client is really key for them to be successful,” Yandle said. “Identifying their core strengths and investing effort to build on that expertise helps them stand out among their competitors.”

That has been true for Neider & Boucher S.C., a 23-lawyer firm in Madison. “When we started the firm 23 years ago, in 1995, we wanted to focus on business law, and that continues,” said founding shareholder and firm president Charles Neider.

The firm also offers services in other practice areas, including estate and succession planning, but staying within the business-related niche has allowed the firm to be very competitive, particularly in the closely held business arena.

“Our profitability has consistently increased every year for the last five years,” Neider said. “It has been a model that has worked well, and we are looking to grow.”

The firm would like to add more attorneys this year, but is not looking to grow for growth’s sake. “Our model is slow growth and careful selection of exceptional people,” Neider said. “We have strict criteria of what we want when we bring people on board.”

Neider says more clients are asking for capped or fixed fees, or other alternative fee structures, than they were five years ago. And boutique firms like his can offer pricing advantages over national firms. But what clients want, primarily, is exceptional service.

“They look to price, but sometimes secondarily,” he said. “They want you to be on the cutting edge, they want you to be responsive and timely, and provide excellent work.”

Some clients also want a diversity of perspectives from their law firms, says Emery Harlan, who has led diversity and inclusion efforts in Wisconsin throughout his career.

“We represent a number of national companies that are very focused on making sure the law firms they work with share their values around diversity and inclusion,” Harlan said. “We have synergy with our clients around diversity and inclusion, and they often look to us for guidance on how to promote diversity among their other law firms.”

Survey Methodology

Constructing an unbiased sample. When reviewing survey results, it’s wise to remember one simple rule: A biased sample will produce biased results. It is the goal of every legitimate survey researcher to construct unbiased samples. While completely excluding all bias is almost impossible, several measures can be taken to reduce sampling error.

A sample should accurately reflect the target population. In this case, the target population was all attorneys in Wisconsin who were identified in the State Bar of Wisconsin membership database as having active status. Due to time and budget constraints, it was necessary to choose a smaller, representative sample that would reflect the larger population of attorneys. The sample was stratified, or subgrouped, by trust account (private practice, corporate counsel, government/academic, and other) proportionately to the distribution in the State Bar database of members. The private practice subgroup was stratified further by region and office size, proportionately to the population distribution. Regions were categorized according to State Bar districts. The total sample numbered 9,000 attorneys.

Looking at the responses. A total of 1,220 usable questionnaires were returned by members, for a 14 percent overall response rate, including 706 from private practitioners, 124 from corporate counsel, 271 from government or public service attorneys, and 119 from those categorized as “other.”

Separate versions of the survey instrument were developed and sent to members of each stratum. The questionnaires were designed so that Part 1 was common across all four versions, while Part 2 contained specific questions for the private practice, corporate/in-house counsel, and government/academic groups. The analysis focused on differences related to practice setting, location, size, and respondent demographics.

Looking at the respondents. Here is a brief profile of the survey’s 1,220 respondents:

- Mean age – 49.3 (mean of State Bar members overall is 50.8)

- Median age – 50 (median of all members is 50)

- Mean and median number of years in practice – 20.7 and 22.0, respectively

- Gender:

- Women – 38 percent (36.4 percent of members overall)

- Men – 62 percent (63.6 percent of members overall)

- Firm or organization size by number of attorneys:

- One – 27 percent

- Two to five – 33 percent

- Six to 10 – 16 percent

- 11 to 25 – 12 percent

- More than 26 –13 percent