One of the most fascinating issues in data protection and privacy is the intersection of humanity and technology; more specifically, how technology such as the algorithm has and is affecting human choice, especially in such areas as economics, politics, and social policy. The concept of human choice (the act of choosing – the act of picking or deciding between two or more possibilities1) is baked into the social contracts of democracies and more specifically into the U.S. Constitution.

Algorithms also are being used in law, for example, in criminal-trial-sentencing recommendations. That leads to an interesting philosophical (and operational) question: Should algorithms determine or recommend criminal sentences?

Algorithms should augment human intelligence, not replace it. Algorithms manipulate information and therefore have significant power within national and global societies.2

This article introduces the serious issues at the intersection of humanity and algorithms and the concept of “nudge.” Nudges result from computer algorithms. The concepts of algorithmic decision-making and algorithmic regulation are also discussed to provide more context to the reader. This article then connects with the broader concern for human choice in an increasingly technocentric world.

Human choice is integrally connected to human autonomy (thestate of existing or acting separately from others)3and free will (freedom of humans to make choices that are not determined by prior causes or by divine intervention).4 These are not simply philosophical issues. They are practical issues with implications for the successful operation of society.

What is an Algorithm? Definitions and Nudges

Definitions of four terms provide detail and context for this discussion.5

James Casey, Dayton 1988, is interim associate vice president, Research and Sponsored Programs, and interim director, Emergent Technologies Institute, at Florida Gulf Coast University. He is a founding adjunct associate professor in the CUNY M.S. in Research Administration and Compliance Program. He represents the State Bar of Wisconsin in the ABA House of Delegates, is vice chair of the ABA e-Privacy Law Committee, and is a past president of the State Bar of Wisconsin Nonresident Lawyers Division. He is a certified privacy practitioner for the EU GDPR data protection officer role.

James Casey, Dayton 1988, is interim associate vice president, Research and Sponsored Programs, and interim director, Emergent Technologies Institute, at Florida Gulf Coast University. He is a founding adjunct associate professor in the CUNY M.S. in Research Administration and Compliance Program. He represents the State Bar of Wisconsin in the ABA House of Delegates, is vice chair of the ABA e-Privacy Law Committee, and is a past president of the State Bar of Wisconsin Nonresident Lawyers Division. He is a certified privacy practitioner for the EU GDPR data protection officer role.

The author gratefully acknowledges the perspectives provided by Attorney Matina Kresta of Athens, Greece. Her comments and viewpoints strengthened the final version of this article.

Get to know the author: Check out Q&A below.

Algorithm: on a computer, a set of instructions for solving a problem or accomplishing a task.6 Every computerized device uses algorithms to perform functions whether through hardware or software.7

Algorithmic decision-making: “the use of algorithmically generated knowledge systems to execute or inform decisions, which can vary widely in simplicity and sophistication.”8 With algorithmic decision-making, human beings (by nature imperfect, thus biased) determine the factors that go into the algorithmic architecture. Thus, human beings steer algorithmic results.9

Algorithmic regulation: “decision-making systems that regulate a domain of activity in order to manage risk or alter behavior through continual computational generation of knowledge from data emitted and directly collected (in real time on a continual basis) from numerous dynamic components pertaining to the regulated environment in order to identify and, if necessary, automatically refine (or prompt refinement of) the system’s operations to attain a specified goal.”10

Algorithms are so embedded in global society today that most people do not know about them or think about them or they accept them without question.

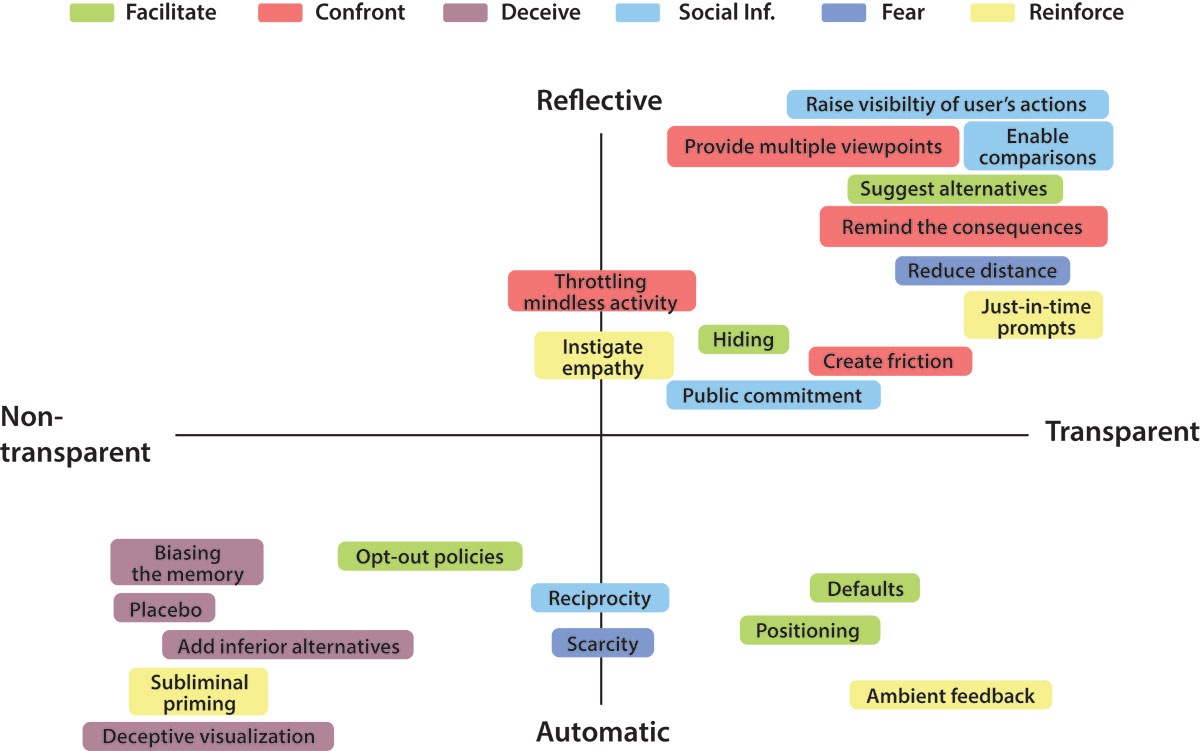

Algorithms lead to nudges. A nudge is defined as “any aspect of a choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any option or significantly restricting choice.”11 One academic article found 23 distinct mechanisms of nudging grouped in six categories and leveraging 15 different cognitive biases.12 The accompanying graphic illustrates those 23 distinct nudge mechanisms.13

Some people would say that a nudge gives you the illusion of absolute choice but that gently coaxing people through software algorithms toward a preferred choice (in other words, being steered) is not absolute choice. While in the legal world, lawyers nudge and coax judges and jurors to a desired outcome all the time, the major difference is that lawyers (as people) are doing the nudging and coaxing under specific rules and circumstances and in accordance with professional standards, while in the algorithmic context machines are doing the nudging and coaxing. This is a significant difference.

In the world of e-commerce, nudges are a central ingredient of online shopping and purchasing activity (Amazon, eBay, and so on). In politics and public policy, algorithms are also being used, such as for online campaigning in the 2016 and 2020 U.S. Presidential elections.

The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal is one prominent example. In 2014, contractors and employees of Cambridge Analytica acquired private Facebook data of tens of millions of Facebook users.14 Cambridge Analytica’s desire to sell the psychological profiles of American voters to political campaigns caused a major crisis within Facebook.15 The crisis spilled over into controversies on both sides of the Atlantic and Congressional inquiry into whether Facebook was doing enough to protect the personal data of users.16

Whether or not we like them, algorithms are all around us. Advances in technology and computing have also led to a more sophisticated version, known as machine learning. Machine learning is necessary for large and complex data sets.

Like many technology issues since the beginning of the internet age in the 1990s, it is often impossible to reverse changes that become part of private and public life. What can be best hoped for, then, is mitigation of certain costs of the post-post-industrial revolution. This is particularly true of algorithms and algorithmic decision-making.

Human Choice, Free Will, and Education

Central to the concepts of democracy in the political realm and capitalism and socialism in the economic realm are the concepts of human choice and free will. These concepts are so pervasive now – at least in advanced democratic societies – that many people in the latter accept them as given … until there is the threat of being deprived of them. Human autonomy, reflected by choice, is a basic human right; it is the essence of humanity.

One way to ensure that the inalienable rights of choice and free will are maintained is through education – specifically, the imperative that people continue to educate themselves. As Thomas Jefferson said in a letter to Uriah Forrest on Dec. 31, 1787:

“Educate and inform the whole mass of people, enable them to see that it is their interest to preserve peace and order, and they will preserve it, and it requires no very high degree of education to convince them of this. They are the only sure reliance for the preservation of our liberty.”17

With the increasing role of algorithms in daily life, it is imperative that the general concept of education as mentioned by Thomas Jefferson be reinforced today. This requires not only increased civics education (recognized by the State Bar of Wisconsin, the American Bar Association, and other professional groups) but also basic education surrounding algorithms and machine learning and how they affect our individual and collective choices.

23 Distinct Nudge Mechanisms

The Intersection of Human Choice and Algorithms

Algorithms are here to stay. They are necessary to process complex and large data sets, but they also present concerns regarding bias, data accuracy, and discrimination because human beings construct the algorithmic architecture and select the data. Algorithms are extremely useful to give human decision-makers suggested courses of action, but human beings must analyze the options presented and make the final decision(s). Like all technological improvements, algorithms and algorithmic decision-making have upsides and downsides.

How do algorithms intersect with the broader questions of “freedom” and “choice”? And how do they apply to the current major public tragedy of our time, the pandemic? Many people say that freedom must always supersede public health. Others think that in situations of a public health emergency, absolute individual choice must temporarily take a back seat to the public welfare (public health).

Given what we know now about the prevalence of algorithms and their influence on the internet – and thus upon people’s beliefs, thoughts, and feelings – how much of that choice and freedom we hear about is truly absolute and is not steered or nudged? Is freedom and choice being “nudged” in the pandemic policy arena? As explained above, biases are built into algorithmic decision-making because human beings, who are imperfect, create the algorithmic architecture for decision-making.18

Where does this reality lead us? It leads us into an uncertain world where lines are increasingly blurred between free human choice and autonomy and nudges toward specific behaviors and outcomes. And given that “Big Data” has quickly gone beyond simple algorithms into machine learning, the implications for the legal, governmental, and private sectors are enormous. These potential implications include:

Court systems increasingly relying on algorithmic recommendations for litigation and decision support;

Governments at all levels using algorithmic decision-making to make low-level decisions, based on convenience and taxpayer savings (primarily in reduced or stagnant staff levels). And at the higher levels of decision-making, strengthened recommendations that will make it harder for elected officials to resist;

The private – and especially the retail e-commerce sector – using increasingly sophisticated algorithmic nudges and prompts to stimulate even greater levels of consumer consumption; and

Political campaigns and advertising using increasingly sophisticated machine-learning technologies to persuade, confuse, and misinform the public.

Conclusion

Where does this percolating battle between algorithms and technology, on one hand, and human choice, on the other, leave us?

Human choice should not be compromised on the altar of convenience. Human choice has already been compromised thanks to the algorithm. This development should concern everyone. Should humankind serve technology, or should technology serve us? I hope that everyone would agree with the latter.

This leads to one final question: How can this percolating battle between human choice and algorithms/technology be mediated? That is a paramount question of our time.

The freedoms enshrined in the U.S. and state constitutions, especially the Bill of Rights, need strengthening in the face of this continual technological onslaught. And a broad federal statute addressing personal data protection and privacy is necessary. These topics are a discussion for a later time.

Meet Our Contributors

How has your career surprised you?

My career has surprised me in many ways, partly because I worked in the “real world” before the widespread use of the internet and email. The practice of law, government, and the private sector have changed so much since then.

My career has surprised me in many ways, partly because I worked in the “real world” before the widespread use of the internet and email. The practice of law, government, and the private sector have changed so much since then.

Such experience provides me with context for mature decision-making. The latter never goes out of style. A former mayor of Milwaukee, Frank P. Zeidler (1912 – 2006), was a model of exemplary leadership. He possessed the qualities of integrity, intelligence, and compassion and believed in the public good and the value of education.

I advise other State Bar of Wisconsin members to constantly challenge themselves. Whatever you do, create value for your community and society. If the pandemic has (or should have) taught us anything, it is to be more humane and considerate toward each other.

It’s also important to be considerate toward yourself. I recharge my own batteries by playing guitar, and the Gibson Les Paul Junior is my axe of choice. Sometimes one pickup is all you need!

James Casey, Florida Gulf Coast University, Fort Myers, Fla.

Become a contributor! Are you working on an interesting case? Have a practice tip to share? There are several ways to contribute to Wisconsin Lawyer. To discuss a topic idea, contact Managing Editor Karlé Lester at (800) 444-9404, ext. 6127, or email klester@wisbar.org. Check out our writing and submission guidelines.

Endnotes

1 www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/choice.

2 For additional background, see the collection of papers within the area of regulation scholarship that were initially presented during a July 2017 joint workshop between King’s College London’s Centre for Law Technology, Ethics & Society and the London School of Economics’ Centre for Analysis of Risk and Regulation. See www.lse.ac.uk/accounting/assets/CARR/documents/D-P/Disspaper85.pdf.

3 www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/autonomy.

4 www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/free%20will.

5 A wide-ranging look at algorithms, machine learning, and other dimensions of artificial intelligence (AI) appears in the Winter 2021 Harvard Business Review special issue, titled How AI is Changing Work.

6 www.investopedia.com/terms/a/algorithm.asp.

7 Id.

8 Karen Yeung, Algorithmic Regulation: A Critical Interrogation, Regulation & Governance 12(4): 507 (2018).

9 Centre for Data Ethics & Innovation, Review into Bias in Algorithmic Decision-making (Nov. 27, 2020), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cdei-publishes-review-into-bias-in-algorithmic-decision-making/main-report-cdei-review-into-bias-in-algorithmic-decision-making.

10 Yeung, supra note 8.

11 Ana Caraban et al., 23 Ways to Nudge: A Review of Technology-Mediated Nudging in Human-Computer Interaction, https://dl.acm.org/doi/fullHtml/10.1145/3290605.3300733.

12 Id.

13 Id.

14 Nicholas Confessore, Cambridge Analytica and Facebook: The Scandal and the Fallout So Far, N.Y. Times (April 4, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/04/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-scandal-fallout.html.

15 Id.

16 Id.

17 Bill of Rights Inst., Civics 101: A Citizens Guide to the Constitution 11, https://citizen.billofrightsinstitute.org/civics-101-ebook/.

18 Centre for Data Ethics & Innovation, supra note 9; Nicol Turner Lee et al., Algorithmic Bias Detection and Mitigation: Best Practices and Policies to Reduce Consumer Harm, Brookings (May 22, 2019), https://www.brookings.edu/research/algorithmic-bias-detection-and-mitigation-best-practices-and-policies-to-reduce-consumer-harms/; James Manyika et al., What Do We Do About the Biases in AI?, Harv. Bus. Rev. (Nov. 6, 2019), https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/overview/in-the-news/what-do-we-do-about-the-biases-in-ai.

» Cite this article: 95 Wis. Law. 24-27 (March 2022).