Mary Lou Munts with First Lady Eleanor

Roosevelt at Swarthmore College circa 1943. Mrs.

Roosevelt deeply influenced Munts’ civic activism,

which propelled her into Wisconsin Democratic

politics. Credit: Munts’ family photo

Lavinia Goodell, Wisconsin’s first woman lawyer, was admitted to the bar in 1874,1 but as recently as 1970, only 3 percent of Wisconsin lawyers were women. The past half century has brought dramatic change: today, the figure is 36 percent (see sidebar).

The full story of women’s rise in the legal profession and the ways in which women have shaped American law has yet to be told, although several writers have made a good beginning for Wisconsin.2 Many studies have focused on “firsts”: the first women admitted to practice, elected to political office, or chosen for the bench in a particular jurisdiction. This article takes a different approach. It introduces five women who are less well known than leaders such as Goodell, Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Shirley Abrahamson, and federal judge Diane Sykes (who are featured elsewhere in this issue) but who also played important roles in shaping Wisconsin law.

Mabel Raef Putnam: Equal Rights with Teeth

The ratification in 1920 of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, giving American women the right to

vote, capped a long struggle by the National Woman’s Party and other suffragist groups. Here, Wisconsin

Gov. John J. Blain shakes the hand of Mabel Raef Putnam, head of Wisconsin’s effort to pass the legislation,

when he signed the Women’s Rights Bill. Photo: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1921, ID 118142.

The ratification in 1920 of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, giving American women the right to vote, capped a long struggle by the National Woman’s Party (NWP) and other suffragist groups. Some groups disbanded after 1920, believing their work was done, but the NWP did not. Women in many states still lacked rights such as the right to serve on juries and to make contracts independent of their husbands. The NWP hoped to persuade Congress and state legislatures to adopt laws confirming such rights, and it selected Mabel Raef Putnam (1888-1966), the head of the NWP’s Wisconsin chapter, to lead the effort in her state.

In early 1921, with help from future Wisconsin Supreme Court justice Charles Crownhart, Putnam prepared a sweeping equal rights act [hereinafter the Act] that gave women “the same rights and privileges under the law as men in the exercise of freedom of suffrage, contract, choice of residence for voting purposes, jury service, holding office, holding and conveying property, care and custody of children, and in all other respects.”

Opposition promptly surfaced: one assemblyman complained that the bill would “coarsen[ ] the fiber of woman” and “take[ ] her out of her proper sphere,” and others balked at the clauses extending full freedom of contract and equal rights “in all other respects.”3 Putnam was not a lawyer, but she proved to be an expert lobbyist and publicist. She issued a steady stream of press releases promoting the Act and generated a massive letter-writing campaign among Wisconsin women’s groups. Her efforts paid off: legislators, in her words, “recalled with an effort the fact that these women back home are now voters,” and in July 1921 the Act became law.4

The NWP’s efforts failed in every other state, and Putnam concluded with some justification that Wisconsin was now “the only place in the English-speaking world where women have equal rights with men.”5 Putnam and her allies worried that the Wisconsin Supreme Court would cabin the law by narrow interpretation, but their fears proved unfounded: in two mid-1920s cases, the court construed the law broadly and indicated that it represented “a necessary genuine social advance.”6 Putnam moved to Chicago around 1930. She left her role as a women’s rights activist and worked as a business journalist and financial adviser, but to the end she remained proud of the Act, which remains her greatest legacy.7

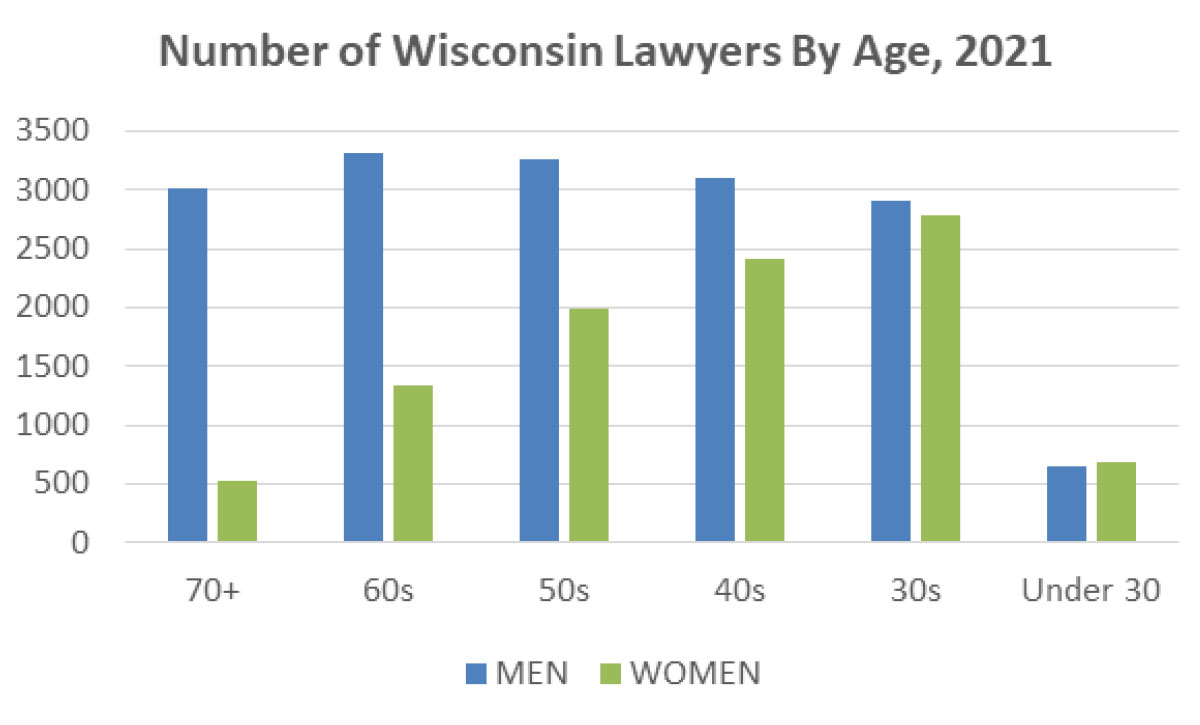

A Tale of Numbers: Women Comprise Majority of Youngest Lawyers

State Bar of Wisconsin statistics tell a dramatic story when it comes to the role of women in the Wisconsin bar. As late as 1970, women made up only 3 percent of the State Bar; as of July 1, 2021, 36 percent of Wisconsin lawyers are women. Women now comprise a majority of the State Bar’s youngest cohort (lawyers under the age of 30), and if this trend continues, women will eventually become a majority of the State Bar.

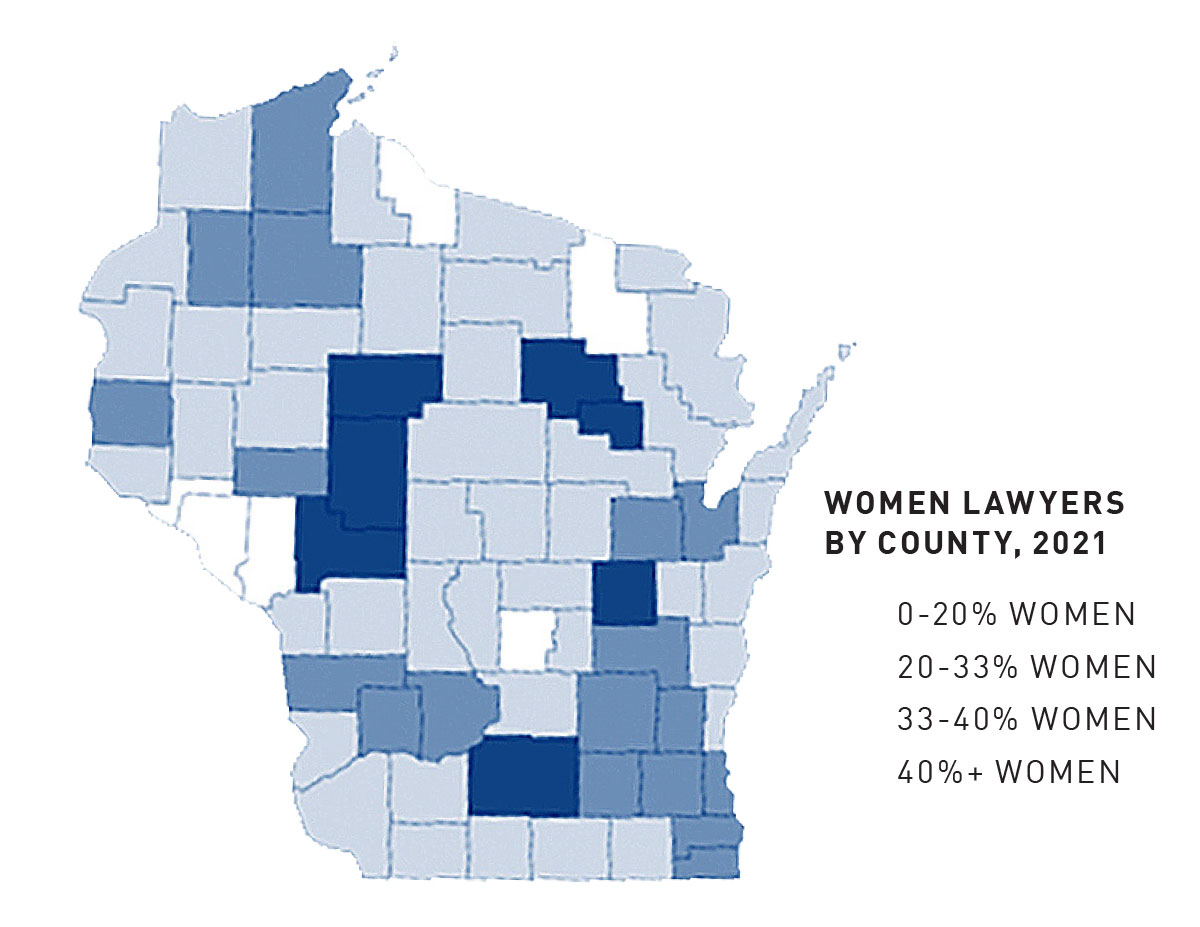

Bar leaders have sometimes expressed concern that rural Wisconsin doesn’t attract sufficient lawyers to meet residents’ needs. One might ask whether rural areas, sometimes stereotyped as socially traditional, have been receptive to women lawyers. There is no evidence of unfriendliness: rural counties account for some of the lowest but also some of the highest proportions of women lawyers, and the geographic distributions of male and female lawyers in Wisconsin are roughly the same overall. Women’s role in the legal profession is increasing steadily and likely will continue to increase in all corners of our state. (The graph and map are based on 2021 statistics provided by courtesy of the State Bar of Wisconsin; the map uses a template provided courtesy of mapchart.net.)

Elsie Ansorge and Dorothy Schmidtkunz: Breaking the Marriage Bar

At the turn of the 20th century, teaching was one of the few professions that welcomed women into its ranks. Thousands of young women became teachers, but as they did so, a “marriage bar” arose. By 1930, about 75 percent of school boards in the United States required new teachers to sign contracts agreeing to leave their jobs when they married. In the words of economic historian Claudia Goldin, school boards provided “reason[s] to fit anyone’s prejudice, ranging from the moralistic[,] that married women with children should be home taking care of their own – to the Victorian[,] that pregnant women would be objectionable in the classroom – to the economic[,] that married women were less efficient and became entrenched.”8

Joseph A. Ranney, Yale 1978, is an adjunct professor and the Adrian Schoone Fellow in Wisconsin Law and Legal Institutions at Marquette University Law School. He recently retired from DeWitt LLP in Madison. He is the author of numerous articles on Wisconsin’s legal history published in Wisconsin Lawyer and elsewhere and several books, including Wisconsin and the Shaping of American Law (2017).

Joseph A. Ranney, Yale 1978, is an adjunct professor and the Adrian Schoone Fellow in Wisconsin Law and Legal Institutions at Marquette University Law School. He recently retired from DeWitt LLP in Madison. He is the author of numerous articles on Wisconsin’s legal history published in Wisconsin Lawyer and elsewhere and several books, including Wisconsin and the Shaping of American Law (2017).

The bar was broken in Wisconsin thanks to the combined efforts of two women, Elsie Leicht Ansorge (1893-1977) and Dorothy Ziegler Schmidtkunz (1909-1995). After marrying in 1926 and being forced out of her teaching position at Green Bay’s vocational school, Ansorge decided not to take her termination quietly: she sued the local school board, arguing that the 1921 equal rights law granted her the right to be employed on the same basis as male teachers. The Wisconsin Supreme Court disagreed, reasoning that the Act gave women teachers the right to contract but did not limit school boards’ right to require gender-specific conditions of employment.9

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Wisconsin teachers pushed for job security in the form of a tenure law guaranteeing that after a probationary period they could be fired only for good cause. The proposal was controversial, but in 1937 the Wisconsin Legislature, then controlled by Progressives, enacted a tenure law. After Schmidtkunz married in 1937 and was terminated from her position at the Carleton School, on Milwaukee’s north side, she decided to challenge the marriage bar based on the new law, even though the law did not refer to the bar. A trial judge ordered her school board to reinstate her and in 1939 the supreme court concurred, holding that the tenure law permitted discharge only for inefficiency or improper behavior – not for marriage.10

Ansorge and Schmidtkunz were neither lawyers nor social activists. Like many women of their time, they wanted to be teachers and wives; they were unusual only in that they saw no incompatibility between the two goals and they were willing to challenge the restriction that prevented them from reaching both goals. By having the courage to do so, they became shapers of their state’s law and benefactors of all women who had suffered from the denial of equal rights.

Mary Lou Munts: Building Modern Marriage Rights

Several people watch as Governor Patrick Lucey, seated at desk, signs the Equal Rights Amendment. Lloyd A. Barbee

(left), Marlin Schneider, two unidentified people, Midge Miller (center), unidentified woman, Mary Lou Munts (right),

David Clarenbach (far right). Photo: Wisconsin Historical Society, ID 97430.

Mary Lou Munts (1924-2013) was born into a well-to-do Chicago family. During college, she became a social activist and was deeply influenced by several meetings with Eleanor Roosevelt. After World War II, Munts did graduate work in economics and eventually moved to Madison with her husband, also an economist, who taught at the University of Wisconsin.11

During the 1950s, highly educated women such as Munts had limited opportunities to use their talents, but the opportunities were growing. In the late 1960s, after raising a family, Munts became active in Democratic politics and enrolled in law school. In 1976 she was elected to the Wisconsin Assembly, a seat she held until 1984 when she was appointed a member of the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin.12 Munts quickly developed a reputation as an approachable legislator, more interested in consensus and practical reform than in posturing. She worked on a variety of issues but became best known for helping secure passage of Wisconsin’s no-fault divorce law (1977) and marital property act (1984).

Before the 1960s, American states required a showing of adultery, cruelty, or other fault on the part of one spouse in order to obtain a divorce. Pressure grew to allow no-fault divorce based on a couple’s own decision that their marriage was irretrievably broken, and in the 1970s the dam broke: during that decade, nearly all states enacted no-fault laws.13

The Wisconsin Legislature held back at first, partly because traditionalists did not want to make divorce too easy and partly because Munts and other reformers felt that early no-fault laws did not give women adequate guarantees of continued economic support. Munts worked to persuade traditionalist lawmakers that reform would do more good than harm and agreed to combine the no-fault standard with a requirement for pre-divorce reconciliation counseling. She also ensured that Wisconsin’s law would give divorcing wives security in the form of clear guidelines for division of marital property and spousal and child support.14 As a result of her work, Wisconsin’s 1977 no-fault law became a model for other states.

During the 1970s, scholars, including U.W. Law School professor June Miller Weisberger, argued that the community property system used in several western states should be adopted nationwide in place of the common-law system. Community property systems give spouses joint ownership of all income and property acquired during marriage. The common-law system, which prevailed in most states including Wisconsin, effectively gave husbands control of most marital assets.

In 1983, reformers prepared a Uniform Marital Property Act (UMPA) and launched a campaign for its adoption throughout the United States, but lawmakers in most common-law states were unimpressed. Munts worked hard to persuade Wisconsin legislators that the UMPA would promote fairness by recognizing the value of women’s work in the home and would reduce marital discord. Using her consensus-building skills and help from legislative allies including future attorney general Donald Hanaway and future federal judge Lynn Adelman, she persuaded lawmakers to adopt a version of the UMPA in 1984, making Wisconsin the only community property state outside the western United States.15

Annette Polly Williams and the Troubled History of School Choice

Annette Polly Williams. Photo: the State of Wisconsin Blue Book 2005-06.

Polly Williams’ life is emblematic of the struggles many Blacks have experienced in forging a life in Wisconsin and of today’s divergence over the best path to Black empowerment. Williams (1937-2014) was born and raised in the Mississippi Delta during the Jim Crow era. She moved to Milwaukee with her family as a child. After graduating from high school, she worked at a variety of blue-collar jobs, raised a family, and eventually went to college, graduating from U.W.-Milwaukee in 1975.

That year, Williams also entered politics. She rose quickly through Democratic Party ranks and in 1980 won election to the Wisconsin Assembly, where she served for 30 years.16 Williams had overcome early adversity and had achieved success through energy and bluntness, and she brought those qualities with her to the legislature. They struck some legislators as abrasive, but they ensured that she would be heard, if not always heeded. Beginning in the late 1980s, Williams applied her energies to the issue that would define her career: school vouchers.

Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) had a long history of segregation. In 1976, federal judge John Reynolds had ordered MPS to undertake desegregation measures. Reynolds’ order produced some integration but it also elicited increased racial conflict in the schools and substantial “white flight” to Milwaukee’s suburbs. Ten years later many Wisconsinites, including Williams, believed that a drastic change was necessary.17 Williams saw Black empowerment as the solution, and in 1989 she turned to school choice, a proposal that would funnel a portion of state education funds into vouchers for use by MPS students to attend private schools of their choosing.

Religious denominations that operated parochial schools and portions of Milwaukee’s business community allied with Williams, and in 1990 the alliance persuaded the legislature to enact the nation’s first school-choice system.18 The school-choice system was controversial from the start: opponents believed the alliance’s true goal was to erode the state’s public-school system and that choice would lead to re-segregation, and the Wisconsin Supreme Court upheld the choice law only by a narrow margin. But Williams was adamant, and she became a national spokesperson for school choice as other states considered following Wisconsin’s lead. Black families, she argued, “have been deprived of resources and access. … Our children … need to see their parents in responsible, powerful positions, so they can feel better about themselves.”19

In later years, Williams grew increasingly disillusioned as the legislature steadily expanded the voucher program, raised family-income limits for eligibility, and included parochial schools within the program’s scope. Williams felt the program was moving away from its initial focus on disadvantaged Black students and toward a general assault on public education, which she had never intended.20 Despite Williams’ own doubts, there is no doubt that she set a national movement in motion, one which continues to be controversial in the Black community as well as the nation at large and likely will remain so for some time.

Kate Kane: Fighting the Power with a Water Glass

In 1879, Kate Kane (1855-1928), the second woman admitted to the bar in Wisconsin, moved to Milwaukee and became that city’s first female lawyer. Kane developed a successful practice representing civil and criminal defendants in the city’s municipal court, but she chafed, privately and publicly, at repeated slights and discrimination by municipal judge James Mallory. By April 20, 1883, she had had enough. When Mallory appointed a political ally to represent a defendant in his court even though it was Kane’s turn for appointment that day, she threw a glass of water in the judge’s face. An incensed Mallory promptly held Kane in contempt and ordered her to pay a fine. She told him she would never pay the fine and Mallory confined her to jail, where she remained for the maximum time allowed by law.

Kane’s action attracted national attention. A Janesville newspaper’s reaction was typical: it stated that the water-glass incident “had lessened her womanhood” and it urged her to “quit the bar and engage in some other business for a living.” The incident hurt Kane’s business but did not cow her. She moved to Chicago where she rebuilt her practice, fought for better treatment of female defendants by the legal system, and was active in women’s suffrage, temperance, and other reform movements.

Kane’s career dramatically illustrates the obstacles early women lawyers faced. They struggled to build practices and often had to rely on clients at the margins of society. They were regarded as curiosities, were condescended to, and were expected to conform to the prevailing stereotype of their sex as the “gentler sex,” an expectation that would persist for more than a century. Many women conformed to the stereotype and tried to turn it to their advantage in the courtroom, but Kane pioneered an alternative model, one of outspokenness. Kane’s method angered some of the men she encountered in her work, but it ensured that she would be heard. Other women lawyers would build on that model as their numbers increased.

For more information on Kane’s career, see Joel E. Black, Citizen Kane: The Everyday Ordeals and Self-Fashioned Citizenship of Wisconsin’s Lady Lawyer, 33 Law & History Review 201 (2015).

» Cite this article: 94 Wis. Law. 40-45 (September 2021).

Meet Our Contributors

What is your favorite hidden-gem website or database?

I do a lot of legal history writing, and as a result I have spent a lot of time in the dustier corners of libraries over the years. COVID-19 and the resultant library shutdown forced me to look for online substitutes, and one gem that I discovered is Hathitrust. Hathitrust is open to anyone; it has put online thousands of books, including many old treatises, legislative reports, constitutional convention reports, legal biographies, and other items that can be useful to practicing lawyers as well as historians. It’s good as a research tool, and it’s also fun to poke around on if you are feeling curious about something!

I do a lot of legal history writing, and as a result I have spent a lot of time in the dustier corners of libraries over the years. COVID-19 and the resultant library shutdown forced me to look for online substitutes, and one gem that I discovered is Hathitrust. Hathitrust is open to anyone; it has put online thousands of books, including many old treatises, legislative reports, constitutional convention reports, legal biographies, and other items that can be useful to practicing lawyers as well as historians. It’s good as a research tool, and it’s also fun to poke around on if you are feeling curious about something!

Joseph A. Ranney, Madison, WI.

Become a contributor! Are you working on an interesting case? Have a practice tip to share? There are several ways to contribute to Wisconsin Lawyer. To discuss a topic idea, contact Managing Editor Karlé Lester at (800) 444-9404, ext. 6127, or email klester@wisbar.org. Check out our writing and submission guidelines.

Endnotes

1 See Catherine B. Cleary, Lavinia Goodell, First Woman Lawyer in Wisconsin, 74 Wis. Magazine of History 243 (Summer 1991).

2 See State Bar of Wis., Pioneers in the Law: The First 150 Women (1998); Joseph A. Ranney, Trusting Nothing to Providence: A History of Wisconsin’s Legal System chs. 9, 21 (1999).

3 Mabel Raef Putnam, The Winning of the First Bill of Rights for American Women 9-12 (1924).

4 Id. at 16-22, 26-47, 49; see generally Samantha Langbaum, “The Paradox of Aspiration and the Making of a Law: The Wisconsin Equal Rights Act of 1921” (M.A. thesis, Univ. of Wis., 1992).

5 Putnam, supra note 3, at 9, 53-54; 1921 Wis. Laws, ch. 529.

6 First Wis. Nat’l Bank v. Jahn, 179 Wis. 117, 190 N.W. 822 (1922); Wait v. Pierce, 191 Wis. 202, 210-12 (1926).

7 (Madison) Capital Times, April 11, 1948. Putnam also wrote a popular financial handbook, What Every Woman Should Know About Finance (1954).

8 Claudia Goldin, Marriage Bars: Discrimination Against Married Women Workers, 1920’s to 1950’s, Nat’l Bur. Econ. Res. Working Paper No. 2747, at 16 (1988); see also Goldin, Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women (1992).

9 Capital Times, March 5, 1929; Ansorge v. City of Green Bay, 198 Wis. 320, 224 N.W. 119 (1929).

10 1937 Wis. Laws, ch. 374; Capital Times, Sept. 9, 1938; State ex rel. Schmidtkunz v. Webb, 230 Wis. 389, 284 N.W. 6 (1939).

11 Jan Uebelherr, As a Wisconsin Legislator, Mary Lou Munts Was “Queen of Consensus,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, Jan. 9, 2014.

12 Id.

13 See, e.g., Herbert Jacob, Silent Revolution: The Transformation of Divorce Law in the United States (1988); Glenda Riley, Divorce: An American Tradition (1991).

14 Uebelherr, supra note 11; 1977 Wis. Laws, ch. 105; see Kurt Dettman, Note, The Displaced Homemaker and the Divorce Process in Wisconsin, 1982 Wis. L. Rev. 941 (1982).

15 1983 Wis. Act 200; see, e.g., June M. Weisberger, The Wisconsin Marital Property Act: Highlights of the Wisconsin Experience, 13 Comm. Prop. L. J. 1 (July 1986); Ranney, supra note 2, at 579-81.

16 Bruce Murphy, The Legacy of Annette Polly Williams, Urban Milwaukee (Nov. 11, 2014); State of Wisconsin, Blue Book 33 (1987-88).

17 See Frank Aukofer, City With A Chance (1968); Ranney, supra note 2, at 547-55; Amos v. Board of Sch. Dirs., 408 F. Supp. 765 (E.D. Wis. 1976).

18 John F. Witte, The Market Approach to Education: An Analysis of America’s First Voucher Program 34-46 (2000); Ranney, supra note 2, at 554-56.

19 Polly Williams, School Choice: A Vehicle for Achieving Educational Excellence in the African-American Community, Heritage Found. Lectures, No. 414, at 2-4 (Feb. 5, 1992); Davis v. Grover, 166 Wis. 2d 501, 480 N.W.2d 460 (1992).

20 Murphy, supra note 16; Witte, supra note 18, at 40-46; see Jackson v. Benson, 218 Wis. 2d 835, 578 N.W.2d 602 (1998) (upholding expansion of voucher program to include parochial schools).