Vol. 75, No. 2, February

2002

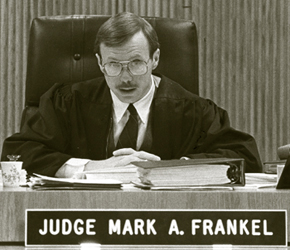

Atypical Career Path is Satisfying

Right on Course

As Mark Frankel has navigated the twists and

turns of his legal career, he's always been where he wanted to be. He

still is.

by Dianne Molvig

LAWYERS' CAREER PATHS MAY have a few bends, minor detours, and even a

sharp turn here or there. But Mark Frankel's nearly 29-year law career

has meandered more than most. "It's not typical, by any stretch," he

concedes.

Now that he's in private practice, Frankel intends to combine his

mediation/ negotiation skills with litigation skills. "I think that's

the wave of the future as far as most litigators are concerned," he

says.

Photo: Janet McMillan

After a brief stint as a sole practitioner right out of law school,

Frankel partnered with two other lawyers to launch a community law

office that represented such clients as the Madison Tenants Union (now

Tenant Resource Center) and United Farm Workers in the mid-1970s. At age

30, he became the state's youngest circuit court judge. He was already a

20-year judicial veteran by the time he hit 50, when he stepped down

from the bench, much to many people's surprise. He then became a

corporate lawyer for Madison Gas & Electric, and two years later, in

September 2001, he made his latest move, circling back to private

practice. Now he's a partner in one of Madison's largest law firms,

LaFollette Godfrey & Kahn.

"I feel I'm in a very good place," Frankel says, sitting in a

conference room with a State Capitol view, on a December morning just

three months into his new job. He perhaps is speaking not only of his

current position and firm, but also in a broader sense about feeling he

is right where he should be in his career and life. Now that he has

returned to private practice, he's focusing on both litigation and

alternative dispute resolution. Everything he's done in the past 29

years has led to this juncture - even if more twists and turns sprang up

along the way than Frankel once would have predicted.

One thing he's always known, however, is that law is his chosen

profession. Growing up in Highland Park outside Chicago, Frankel decided

at a young age that he wanted to follow in the footsteps of his father,

a highly respected attorney. His mother also influenced his aspirations.

"She instilled in me that it was her obligation and mine to make the

world a better place," Frankel says. For example, she spurred her son to

participate in the Selma-to-Montgomery civil rights march when he was

just 16, and to work in Chicago's Cabrini-Green housing project in

summers during high school.

When Frankel graduated from the U.W. Law School in 1973, he aimed to

land a job somewhere in the country working on prison law reform. To

tide him over while he searched, he set up a sole practice in Madison.

Soon he joined Lester Pines and Harold Langhammer in opening a community

law office. The prison reform job never materialized, but the community

law practice took off. There Frankel got his chance, after all, to

advocate for prisoners' rights, and to handle a diverse array of civil

and criminal defense cases. He also worked on other social justice

issues, such as migrant labor law and tenants' rights, and helped to set

up the Dane County Rape Crisis Center. His social activist tendencies

carried over into his private life, too. He volunteered as a Big

Brother, and he was a foster parent to a 16-year-old boy, at whose

wedding Frankel would officiate some 20 years later.

After only six years in practice, Frankel spotted another opportunity

he simply couldn't pass up. The idea of serving on the bench had been

"just a glimmer in the back of my mind," he notes, dating back to when

he'd served as a clerk for Judge James Doyle Sr. during law school. Then

in 1979, Dane County created two new circuit court branches, which meant

elections for two new judgeships with no incumbents. Frankel knew this

situation might not arise again for years, so he decided to run. "I was

young and brash, I guess, and figured I had little to lose," he says.

Indeed, he won, with his history of community activism being a major

factor in garnering voters' support.

Acclimation and Innovation

Once Frankel was elected, his key initial challenge as a new judge

was to be taken seriously by all who appeared before him. Could this

left-leaning, 30-year-old lawyer with only six years of practice

experience be judge material? "I'm sure there was some degree of

skepticism," Frankel acknowledges.

As he acclimated to being on the bench, "what I found most

difficult," he recalls, "was finding a comfortable dynamic in managing

the lawyers in court." He soon learned a lesson perhaps useful to judges

of all ages and tenures. People in black robes tend to come across as

solemn figures in the first place, but as a young judge out to prove

himself, Frankel may have tried extra hard to present a serious demeanor

in the courtroom. Feedback he heard from lawyers said, in essence,

"Lighten up." He took this advice to heart.

"I mistakenly believed that if I was diligent and serious about the

job, that was all that was required of me," Frankel says. "But in

addition to having a thoughtful judge and getting a good decision,

lawyers want a judge who's a friendly, warm human being, because they're

spending a difficult time in the courtroom. A judge who has a sense of

humor and a human touch is more effective than one who's all

business."

Thus, Frankel had to make adjustments to fit into his new role. But

he also felt the system itself could stand some adjustments. "One of my

goals was to be innovative," he says. "If I could think of different

ways of doing things that were nontraditional but made more sense, I'd

give them a try."

One such innovation was in how Frankel related to juvenile offenders

in the courtroom. As juvenile court judges often do, he'd say a few

words to a young offender at the close of a trial, trying to "get

through." But Frankel quickly became frustrated with the process. "Many

of these kids were tuned out to almost any adult authority figure," he

recalls. "They'd sit back in their chairs, roll their eyes, and wonder,

'When is this old guy going to get done with this lecture I don't want

to hear?'"

So he tried a different approach. At the close of a trial, he would

call the defendant up to the bench, extend his hand for a firm

handshake, and look the young person straight in the eye while they

talked. It was a way to bridge the distance, in more ways than one,

between the bench and the defendant's table. "It was a different level

of personal connection," Frankel notes. "I'd frequently see tears in

their eyes. I can't tell you that every time I had a salvaged soul. But

I felt there was a much more meaningful human interaction going on."

Improving human interaction in divorce cases was another of Frankel's

goals as judge. He saw divorce trials as painful for all involved:

litigants, lawyers, and even judges. Again, Frankel looked for another

way. "I found I could save everybody time, money, and anguish," he says,

"by giving the lawyers the feedback they needed in order to resolve the

case themselves." He was, in effect, using alternative dispute

resolution, at a time when it was still fairly uncommon.

Frankel's approach unsettled some divorce attorneys. "The key to the

process that I don't think all lawyers figured out," says Madison

attorney Allan Koritzinsky, "was that you had to be extremely

well-prepared and able to think on your feet. You had to have your

client's priorities in mind and be able to succinctly present his or her

case." Lawyers who could operate in that mode, he adds, did well in

divorce mediations before Frankel; those who couldn't weren't as

comfortable with the process.

But, in time, lawyers and parties alike came to expect that if a

divorce went to Frankel's court, it would be mediated with him, not

litigated before him. "He would take whatever time it took," Koritzinsky

says, "and expend whatever energy necessary to get it done."

Wider Influences

"One of my goals was to be innovative. If I could think of different

ways of doing things that were nontraditional but made more sense, I'd

give them a try."

Photo: A. Craig Benson

Other changes Frankel implemented reached beyond the walls of his own

courtroom. In the mid-1980s, he recognized the need to revise sentencing

practices for drunk driving. At the time, all drunk-driving offenders

who pled guilty received the same mandatory minimum sentence. "I didn't

think it made sense to treat everybody the same," he says, "because some

forms of drunk driving clearly are more aggravated than others."

So Frankel drafted new sentencing guidelines to differentiate levels

of seriousness of drunk-driving offenses. His Dane County colleagues

approved the guidelines, and soon several other counties adopted them as

well. Eventually, the state Legislature made these sentencing guidelines

mandatory statewide.

In another shift from tradition, Frankel was the first judge in the

state to allow jurors to ask questions during trials, an idea he first

heard a Michigan federal judge speak about at a national conference.

Frankel believed that jurors, who were making crucial decisions, ought

to have the right to ask questions, just as judges do. It was, he

admits, a practice that initially made lawyers nervous, and still often

does. Attorneys fear a juror will ask the very question they are hoping

opposing counsel will fail to ask.

In the final analysis, however, it comes down to a conflict between

protecting a lawyer's right to take advantage of opposing counsel's

tactical omissions and jurors' confusion about the facts, and the need

to search for the truth, Frankel contends. "That's an easy balance to

strike," he says, "in favor of the jury's right to understand what it is

they're grappling to resolve."

Still, jury questioning hasn't caught on with judges as much as it

might, Frankel believes. As for lawyers, he says they have less to fear

from jury questions than they think. The way the process works is that

jurors don't blurt out questions; they write them down and pass them to

the judge, who then goes over the questions with both attorneys, out of

hearing of the jury. Attorneys can object to questions, judges can

rephrase troublesome ones before they're asked, and lawyers can ask

followup questions of the witness. In fact, Frankel sees advantages to

attorneys. "They get some early indications, albeit rough, of what the

jury is thinking," he notes, "and what the jury's level of understanding

may be," which can help lawyers adjust their case presentation

midstream.

What's more, jury questioning wins high marks with jurors, Frankel

reports. "I met with jurors after trials," he says, "and almost

uniformly they were delighted to have had the opportunity to ask

questions, even if they didn't use it. They didn't feel like the 'potted

palms' they are in a courtroom where they're told to just sit there and

listen, but not speak."

New Directions

After two decades on the bench, Frankel still felt challenged in his

judicial role. But he also grew more aware of what he was missing.

Increasingly, parties in major, complex civil disputes were taking their

conflicts to settings other than courtrooms. As a judge, Frankel saw

fewer opportunities to be involved in resolving conflicts, which was the

aspect of his job he most enjoyed. He also felt drawn to the idea of

working in a more collaborative environment, unlike the relatively

solitary worklife of a judge.

So when Madison Gas & Electric offered Frankel a position as

general counsel, he accepted. After two years, desiring to work with a

broader array of clients and to delve still deeper into corporate

problem solving and dispute resolution, Frankel migrated to his current

position at LaFollette Godfrey & Kahn.

About a year before he left the bench in 1999, Frankel passed through

another major life transition. He and his wife Sherrie Gruder had a baby

girl, Jamie, adding one more to their family of three, including

Frankel's teenage stepdaughter Chelsey. After Jamie was born, Frankel

took a five-month paternity leave from the bench so he could be with her

full-time. It was another instance in his career when he broke away from

the norm. While he may not be the only judge in the state to take an

extended paternity leave while in office, he's certainly among only a

few.

"It was in no way surprising to me that he did that," says Dane

County circuit judge Michael Nowakowski, one of Frankel's former

softball teammates and judicial colleagues. "In fact, I would have been

surprised if he'd failed to do that. I knew how thrilled Mark was over

the prospect of being a parent."

Indeed, Frankel had no doubts about his priorities. "I was an old-guy

parent when Jamie was born," he notes. "I'd waited a long time to have

my own child. And I was going to make the most of it."

That latter comment seems to apply to his outlook on his newest

career venture as well. Frankel, now 53, intends to make the most of his

experience in client advocacy, litigation, mediation, and acting as a

neutral decision-maker, in his work with clients ranging from small

businesses to multinational corporations to government entities. "One of

my big interests going forward," he says, "is to combine my

mediation/negotiation skills with litigation skills. I think that's the

wave of the future as far as most litigators are concerned."

Wisconsin

Lawyer