Vol. 78, No. 3, March

2005

The Sophisticated User Doctrine Arrives

The sophisticated user doctrine may insulate a manufacturer from a

negligence claim when a person or company that purchases a product as

knowledgeable as the manufacturer about the product's hazards. The

doctrine may have arrived, but questions remain about its scope, among

other issues.

Sidebars:

by

Kevin D. Trost

by

Kevin D. Trost

Last summer the Wisconsin Supreme Court tacitly gave manufacturers in

Wisconsin another defense against lawsuits that allege a manufacturer

negligently failed to provide adequate warnings with its products. In

Haase v. Badger Mining Corp.,1 the

court let stand without comment a published court of appeals decision

that borrowed the sophisticated user doctrine from Iowa law. The supreme

court declined to address the lower court's importation of the

sophisticated user doctrine, citing the appellant's failure to appeal

the negligence claim that was dismissed under that doctrine. This

silence has solidified the lower court's published ruling, and a

subsequent court of appeals decision that invokes this ruling, and it

has opened the door to the introduction of the sophisticated user

doctrine in Wisconsin jurisprudence.

What is the Sophisticated User Doctrine?

The sophisticated user doctrine insulates a manufacturer from

negligence claims that are based on the failure to warn. When the person

or entity purchasing a product is as knowledgeable about the product's

hazards as the manufacturer is, the manufacturer bears no duty to warn

the purchaser of the hazards. In such a situation the purchaser is

considered to be more knowledgeable about the end use of the product and

is therefore in a better position than the manufacturer to provide

meaningful warnings and instructions to anyone actually using the

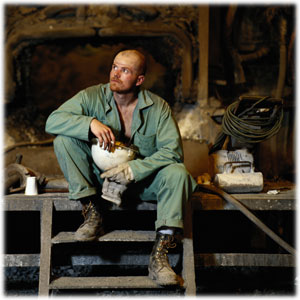

product.2 For example, a foundry that

purchases sand for use in its casting operations is in a better position

than the sand manufacturer to communicate to foundry employees the

dangers of the product and to instruct in proper protective

measures.

Kevin D. Trost, U.W. 1998, is a senior associate at

Axley Brynelson LLP, Madison. His practice is concentrated in the areas

of products liability, personal injury, and environmental litigation. He

has both defended and prosecuted failure to warn claims affected by the

sophisticated user doctrine.

Kevin D. Trost, U.W. 1998, is a senior associate at

Axley Brynelson LLP, Madison. His practice is concentrated in the areas

of products liability, personal injury, and environmental litigation. He

has both defended and prosecuted failure to warn claims affected by the

sophisticated user doctrine.

This doctrine is rooted in Restatement (Second) of Torts § 388

(1965), a specific section that Wisconsin has adopted.3 This section of the Restatement states:

"Chattel Known to be Dangerous for Intended Use.

"One who supplies directly or through a third person a chattel for

another to use is subject to liability to those whom the supplier should

expect to use the chattel with the consent of the other or to be

endangered by its probable use, for physical harm caused by the use of

the chattel in the manner for which and by a person for whose use it is

supplied, if the supplier

"(a) knows or has reason to know that the chattel is likely to be

dangerous for the use for which it is supplied, and

"(b) has no reason to believe that those for whose use the chattel is

supplied will realize its dangerous condition, and

"(c) fails to exercise reasonable care to inform them of its

dangerous condition or of the facts which make it likely to be

dangerous."

Subsection (b) has been widely interpreted to embody the

sophisticated user doctrine and to establish that there is "no duty to

warn if the user knows or should know of the potential danger,

especially when the user is a professional who should be aware of the

characteristics of the product."4

The Emergence of the Doctrine in Wisconsin

The Wisconsin Court of Appeals first explicitly raised the doctrine

and Restatement (Second) of Torts § 388(b) as its grounds for

dismissing a plaintiff's claim in Haase v. Badger Mining

Corp.5 Haase, a long-term employee of

the Neenah Foundry, was diagnosed with silicosis. He then sued Badger

Mining, the company that provided the foundry with silica sand.6 The foundry casting process pulverizes the silica

sand, creating clouds of visible silica dust and silica particles so

minute that they can become lodged in the lungs of exposed

workers.7 The particles cannot be expunged

from the lungs and can cause the progressive respiratory disease

silicosis. Haase argued that the seller of the sand knew that foundries

were one of the prime consumers of its sand, knew that silica sand broke

down into minute respirable particles during the foundry casting

process, and failed to warn workers how to adequately protect themselves

from respiratory harm.8 Both the trial court

and the court of appeals agreed with Badger Mining that the Neenah

Foundry was as sophisticated and knowledgeable as Badger Mining about

the dangers of silicosis and how to protect workers from respirable

silica.9 As a result, the sophisticated user

doctrine relieved Badger Mining of its duty to provide a specific

warning to the foundry workers.

After Haase, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals quickly extended

the reach of the sophisticated user doctrine beyond the

employer/employee context. In Mohr v. St. Paul Fire & Marine

Insurance Co., a high school swim team member was injured while

diving from a diving board into a shallow portion of the high school's

swimming pool.10 The swimmer sued the

diving board manufacturer, claiming the manufacturer was negligent for

failing to warn him of the dangers of locating the platform at a shallow

depth.11 The manufacturer contended it bore

no duty to warn because the high school was a sophisticated user that

belonged to the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association (WIAA),

an organization that monitors national standards and provides its member

high schools with information on the safe practice of sports

activities.12 The Wisconsin Court of

Appeals found that the sophisticated user doctrine was applicable, but

determined there was insufficient factual information about the extent

of the manufacturer's knowledge about the high school to uphold the

manufacturer's motion for summary judgment.13

Rather than exclusively examining the purchaser's level of knowledge,

as the Haase court did, the Mohr court

focused on the manufacturer's level of knowledge about the purchaser.

Mohr explicitly stated that "the issue under Restatement

(Second) of Torts § 388(b), correctly framed, is whether KDI

had reason to believe that the high school had knowledge the

platforms were likely to be dangerous if used in less than five feet of

water."14 The court of appeals explained

that while the purchaser's "actual knowledge is not dispositive under

§ 388(b)," it is "relevant if KDI knew of it or if the knowledge of

this high school may be reasonably inferred to be the knowledge of high

schools in general who purchase the product...."15

The Future Application of the Doctrine in Wisconsin

In Mohr, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals clearly centered the

spotlight of the sophisticated user inquiry on the manufacturer's level

of knowledge. What remains unclear is what level of knowledge a

manufacturer must possess in order to be granted refuge under the

doctrine. It is not known whether a manufacturer is protected if it knew

that the purchaser's industry had knowledge about a hazard, or if a

manufacturer must be aware that the specific purchaser knew of the

hazard. How future courts interpret the level of knowledge required by

manufacturers for protection under the doctrine will likely determine

the potency of this defense in Wisconsin.

Future judicial consideration of at least two other issues also will

affect the ultimate scope of this doctrine in Wisconsin. To date the

Wisconsin Court of Appeals has only applied this doctrine to warnings

claims rooted in negligence, failing to move further because the courts

in Haase and Mohr only addressed claims rooted in

negligence.16 Other states that have

adopted the doctrine have blurred any distinction between a warnings

claim based in negligence and a warnings claim based in strict

liability.17 There is reason to believe

that Wisconsin courts will apply the sophisticated user doctrine to both

types of warnings claims. The court of appeals in Mohr

explicitly refused to further expand the scope of this doctrine without

guidance from the Wisconsin Supreme Court; however, it questioned

outright whether there was any "practical significance" between a strict

liability warnings claim and a warnings claim rooted in

negligence.18 This stance is consistent

with the court of appeals' previous statement that the proof

requirements for warnings claims in negligence and in strict liability

are essentially the same.19

Additionally, future courts may be asked to consider the policy

argument that the sophisticated user doctrine burdens employees with

bearing too great a share of the costs of their injuries. Plaintiffs'

attorneys are concerned that adopting this doctrine will unjustly

foreclose an avenue of recovery for innocently injured plaintiffs. The

Wisconsin Court of Appeals explained that the adoption of the doctrine

"places the duty to warn on the party arguably in the best position to

ensure workplace safety, the purchaser-employer."20 However, the doctrine effectively allows a

manufacturer to transfer responsibility and liability to employers for

warning workers who ultimately use a manufacturer's product. While in

some states this shift of liability may not affect a worker's ability to

pursue an action against the employer, Wisconsin has strict civil

immunity for employers under its worker's compensation laws. If the

sophisticated user doctrine allows the transfer of liability to the

employer, and the employer is protected by worker's compensation

immunity, the injured employee will be left with only the limited

recovery available through worker's compensation.

National Trend

Over the last two decades a number of states have incorporated the

sophisticated user doctrine into law as a protection for manufacturers,

with few states rejecting the doctrine outright.21 Wisconsin is one of several states to recently

consider adopting this doctrine. In the most recent decision in which a

state court adopted the doctrine, the Texas Supreme Court set out a

series of factors for its courts to consider when determining whether

the manufacturer bears a duty to warn.22

The Minnesota Court of Appeals, relying on the same case that the

Haase court relied on, invoked the doctrine to dismiss a claim

against the same silica sand supplier that was sued in

Haase.23 However, the Minnesota

Supreme Court recently overruled the decision, finding an insufficiency

of evidence on key issues.24 In doing so,

the court distinguished between what it termed a sophisticated user

defense and a sophisticated intermediary defense.25 The court acknowledged that a manufacturer has

no duty to warn under a sophisticated user defense when the actual user

is as knowledgeable about the product and its dangers as is the

manufacturer.26 In contrast, the court

refused to decide whether it would relieve a manufacturer of its duty

when the product's purchaser (the sophisticated intermediary) is as

knowledgeable as the manufacturer but the actual user may not be

knowledgeable.27

Conclusion

The adoption of the sophisticated user doctrine in Wisconsin is in

itself a boon for manufacturers who are plagued with claims that they

inadequately warned of the dangers posed by their products. The doctrine

likely will be expanded to apply to strict liability claims. However,

future interpretation of how this doctrine will be applied in Wisconsin

may serve to limit its use. Under Mohr, whether the doctrine

applies in a particular case turns on the manufacturer's level of

knowledge about the purchaser and the purchaser's industry. Questions

remain about how much a manufacturer must know before it is relieved of

a responsibility to warn. Must the manufacturer know that the purchaser

is aware of the general dangers posed by the product, or must the

manufacturer know that the purchaser is aware of dangers associated with

the purchaser's specific use of the product? Alternatively, perhaps it

is sufficient that a manufacturer know that a purchaser is an active

member of a knowledgeable professional or industry group. Courts'

guidance on these issues will provide counsel with a better

understanding of the potency of the sophisticated user defense and its

effect on the landscape of failure to warn claims in Wisconsin.

Endnotes

12004 WI 97, 274 Wis. 2d 143, 682

N.W.2d 389, affirming 2003 WI App 192, 266 Wis. 2d 970, 669

N.W.2d 737 (adopting and applying rationale of Bergfeld v. Unimin

Corp., 319 F.3d 850 (8th Cir. 2003)).

2Haase, 2003 WI App 192,

¶ 21, 266 Wis. 2d 970.

3Strasser v. Transtech Mobile

Fleet Serv. Inc., 2000 WI 87, ¶ 58, 236 Wis. 2d 435, 613

N.W.2d 142.

4Bergfeld v. Unimin Corp.,

319 F.3d 350, 353 (8th Cir. 2003).

5Haase, 2003 WI App 192,

¶ 21, 266 Wis. 2d 970. Wisconsin courts have previously recognized

that "there is no duty to warn members of a trade or profession about

dangers generally known to the trade or profession." Shawver v.

Roberts Corp., 90 Wis. 2d 672, 686, 280 N.W.2d 226 (1979). However,

the Shawver court did not refer to this principle as the

sophisticated user doctrine.

6Haase, 2003 WI App 192, ¶ 1,

266 Wis. 2d 970.

7Id. ¶ 3.

8Id. ¶ 1.

9Id.

10Mohr v. St. Paul Fire &

Marine Ins. Co., 2004 WI App 5, 269 Wis. 2d 302, 674 N.W.2d

576.

11Id. ¶ 6.

12Id. ¶ 14.

13Id. ¶ 21.

14Id. ¶ 20.

15Id.

16Id. ¶ 34.

17See, e.g., Phillips v. A.P.

Green Refractories Co., 630 A.2d 874 (Pa. Super. Ct. 1993),

aff'd sub nom. Phillips v. A-Best Prods. Co., 665 A.2d 1167

(Pa. 1994); Donahue v. Phillips Petroleum Co., 866 F.2d 1008

(8th Cir. 1989) (applying Missouri law).

18Mohr, 2004 WI App 5,

¶ 32 n.10, 269 Wis. 2d 302; see also Nigh v. Dow Chemical

Co., 634 F. Supp. 1513, 1517 (W.D. Wis. 1986) ("The Court will

leave the task of distinguishing between negligence and strict liability

in the duty to warn to those who count angels on the heads of

pins.").

19Mohr, 2004 WI App 5,

¶ 32 n.10, 269 Wis. 2d 302. (citing Tanner v. Shoupe, 228

Wis. 2d 357, 365 n.3, 596 N.W.2d 805 (Ct. App. 1999); Krueger v.

Tappan Co., 104 Wis. 2d 199, 207 n.3, 311 N.W.2d 219 (Ct. App.

1981)).

20Haase, 2003 WI App

192, ¶ 21, 266 Wis. 2d 970; contrast with Gray v. Badger Mining

Corp., 664 N.W.2d 881, 885 (Minn. Ct. App. 2003) ("in the

industrial setting ... the employer is not motivated to warn

employees because the employer's liability is limited by the worker's

compensation laws."), rev'd, 676 N.W.2d 268 (Minn. 2004),

and Humble Sand & Gravel Inc. v. Gomez, 146 S.W.3d 170,

184-85 (Tex. 2004) ("disregard [by employers] of the risks to their

employees of inhaling silica dust was not for want of additional

information that flint suppliers should have furnished, but for want of

care.").

21See Phillips v. A.P. Green

Refractories Co., 630 A.2d 874 (Pa. Super. Ct. 1993),

aff'd, 665 A.2d 1167 (Pa. 1994); Jodway v. Kennametal

Inc., 525 N.W.2d 883 (Mich. Ct. App. 1994); Groll v. Shell Oil

Co., 196 Cal. Rptr. 2d 52, 54 (Cal. Ct. App. 1983); Smith v.

Walter C. Best Inc., 927 F.2d 736, 741 (3d Cir. 1990); Goodbar

v. Whitehead Bros., 591 F. Supp. 552, 561 (W.D. Va. 1984),

aff'd sub nom. Beale v. Hardy, 769 F.2d 213 (4th Cir. 1985);

Damond v. Avondale Indus. Inc., 718 So. 2d 551, (La. Ct. App.

1998), writ denied, 735 So. 2d 637 (La. Ct. App. 1999). But

see Sharp v. Wyatt Inc., 627 A.2d 1347 (Conn. App. Ct. 1993)

(sophisticated user doctrine is not affirmative defense but rather part

of user awareness issue to be considered by trier of fact).

22Humble Sand & Gravel

Inc., 146 S.W.3d at 192-94. Those factors, applied to a situation

involving abrasive blasting, are: 1) the likelihood of serious injury

from a supplier's failure to warn; 2) the burden on a supplier of giving

a warning; 3) the feasibility and effectiveness of a supplier's warning;

4) the reliability of operators to warn their own employees; 5) the

existence and efficacy of other protections; and 6) the social utility

of requiring, or not requiring, suppliers to warn. Id.

23Gray, 664 N.W.2d at

887.

24Gray v. Badger Mining

Corp., 676 N.W.2d 268, 277 (Minn. 2004).

25Id. at 276-77.

26Id.

27Id. at 277.

28See Moore ex. rel. Moore v.

Memorial Hosp. of Gulfport, 825 So. 2d 658, 664-65 (Miss. 2002)

(listing states that have adopted learned intermediary doctrine).

See also Kevin L. Colbert & John Gray, Recent

Developments in Toxic Tort and Environmental Litigation, 38 Tort

Trial & Ins. Prac. L.J. 691 (Winter 2003).

29Vitanza v. The Upjohn

Co., 778 A.2d 829, 844-47 (Conn. 2001).

30Kurer v. Parke, Davis &

Co., 2004 WI App 74, 274 Wis. 2d 390, 679 N.W.2d 867.

31Id. ¶ 31 n.7.

Wisconsin Lawyer