In the near future, Wisconsin will be required to redraw its Congressional and legislative districts based on 2020 federal census data. (See sidebar.) The redistricting process after the last census was highly contentious even though one party controlled state government. In 2021, with political control divided between a Democratic governor and a Republican-majority legislature, it is likely to be even more so. Redistricting fights have a long history in Wisconsin, which, together with recent federal decisions arising out of the post-2010-census fight, provide clues to the possible battles ahead. This article examines those clues.

Gerrymandering: A Wisconsin Tradition

Gerrymandering – designing electoral districts to give political advantage to a particular group – can take different forms. Regional gerrymandering came first. During the 1700s and early 1800s, most American colonies and states allocated a fixed number of representatives to each organized district regardless of population, but as the frontier filled up, established districts were reluctant to cede power by creating new districts or allotting extra representatives to growing districts. Demands for population-based apportionment grew; Pennsylvania adopted a population-based apportionment system in 1776, and by 1835 nearly all states had followed suit.1

Joseph A. Ranney, Yale 1978, is an adjunct professor and the Adrian Schoone Fellow in Wisconsin Law and Legal Institutions at Marquette University Law School. He recently retired from DeWitt LLP in Madison. He is the author of numerous articles on Wisconsin’s legal history published in Wisconsin Lawyer and elsewhere and several books, including Wisconsin and the Shaping of American Law (2017). Learn more about our contributor.

Joseph A. Ranney, Yale 1978, is an adjunct professor and the Adrian Schoone Fellow in Wisconsin Law and Legal Institutions at Marquette University Law School. He recently retired from DeWitt LLP in Madison. He is the author of numerous articles on Wisconsin’s legal history published in Wisconsin Lawyer and elsewhere and several books, including Wisconsin and the Shaping of American Law (2017). Learn more about our contributor.

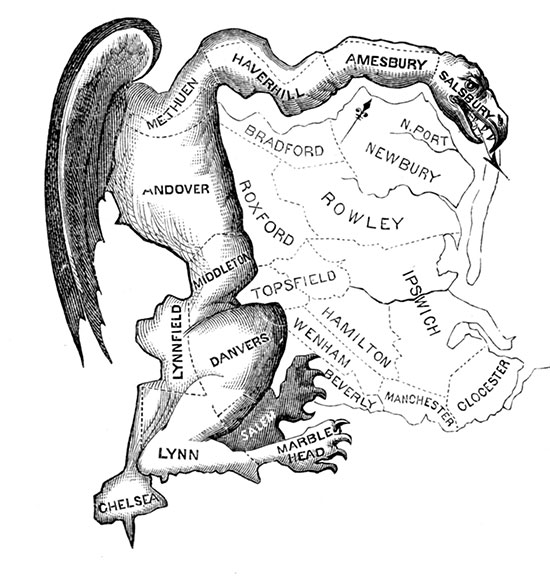

Partisan gerrymandering came next, most famously in 1812 when the Massachusetts Legislature created a salamander-shaped district that gave gerrymandering its name. (See sidebar.) The new practice spread throughout the United States, triggering calls for requirements that legislatures be comprised of single districts consisting of “contiguous” territory to ensure that political minorities and local communities would have at least some representation.2

Delegates to Wisconsin’s 1846 and 1847-48 constitutional conventions agreed with the equal-population and single-district principles, but they also regarded counties as essential to the state’s settlement and organization and believed county boundaries should play a role in the districting process. The delegates created a hybrid system that remains in the Wisconsin Constitution: After each federal census, the legislature must reapportion itself “according to the number of inhabitants,” using “single districts” that are “bounded by county, precinct, town or ward lines, to consist of continuous territory and be in as compact form as possible.”3

Redistricting disputes began almost immediately after statehood. In 1851, Gov. Nelson Dewey, a Whig, vetoed the Democratic-majority legislature’s apportionment act as too partisan. In 1890, Democrats gained temporary control after decades of Republican dominance and tried to redistrict the state to their advantage.

In State ex rel. Attorney General v. Cunningham (1892), one of the first American cases to address gerrymandering, the Wisconsin Supreme Court struck down the Democrats’ plan and established several basic principles. It suggested that although redistricting challenges would typically be made by the governor or attorney general, individual voters also had an interest in statewide redistricting: Gerrymandering, said Justice Silas Pinney, “affects … no one particular class of people or locality, but all the people of the state.” The court stressed that districts must be “as close an approximation to exactness [of population] as possible” but also emphasized that redistricting must also respect county lines as much as possible.4 Several months later the court struck down a second plan proposed by Democrats, and the state was not redistricted until 1896.5

The Wisconsin Supreme Court took a more deferential stance as new redistricting battles emerged in the 20th century. In 1932 it upheld a redistricting plan, choosing to defer to the Wisconsin Legislature despite concerns about population inequalities.6 The legislature failed to reapportion itself after the 1940 census, but in 1946, in State ex rel. Martin v. Zimmerman, the supreme court rejected a request that it compel the legislature to do so. The justices relied on Colegrove v. Green, a then-recent U.S. Supreme Court decision holding that state legislative apportionment was a political matter with which courts had no right to interfere,7 and they reaffirmed their position when the legislature’s post-1950-census reapportionment plan was challenged.8

Reapportionment law underwent a revolution during the early 1960s. In Baker v. Carr, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Colegrove’s holding, and in Reynolds v. Sims, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the U.S. Constitution’s equal-protection provisions require state legislatures to equalize district populations.9 The federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibited state legislatures from discriminating against protected racial groups in the redistricting process, and federal courts read the prohibition to require that districts in areas with a high minority population be drawn so as to maximize minorities’ opportunity to be heard through legislators of their own choice.10

The Wisconsin Supreme Court responded to Baker and Sims by reversing its hands-off approach. In 1964, in State ex rel. Reynolds v. Zimmerman, it struck down a reapportionment plan based on impermissibly high population inequalities.11 The supreme court gave the Wisconsin Legislature an opportunity to enact a modified plan but held that it had power to formulate its own plan if the legislature deadlocked or failed to take action. The court tried to honor the tradition of matching counties with districts, holding that the counties could not be combined with parts of other counties, but in 1969 Wisconsin Attorney General Robert Warren advised that Sims and other federal decisions mandating strict population equality made that tradition and the Wisconsin Constitution’s related limits nonbinding.12

The 1980, 1990, and 2000 elections each produced divided government and partisan deadlock over reapportionment in Wisconsin. Population shifts during each preceding decade made reapportionment mandatory under Sims, and the task now fell to the federal courts. The federal judges in charge of the post-1980 reapportionment invited political parties and other interested groups to propose maps, but the judges ultimately created their own map, designed to keep population variations between districts to two percent or less.13

In Baumgart v. Wendelberger, the judges tasked with the post-2000 reapportionment summarized the factors to be considered in the post-Sims legal world. Equality of population remained the primary concern; “wards and municipalities [should] be kept whole where possible,” in deference to the drafters’ wishes expressed in the Wisconsin Constitution; and “maintaining traditional communities of interest” and “avoiding the creation of partisan advantage” also were important factors.14

Population Shifts and Redistricting

Population shifts often mean that legislative districts equal in population in one census become unequal, sometimes unconstitutionally so, at the next census. That will be the case for Wisconsin this year.

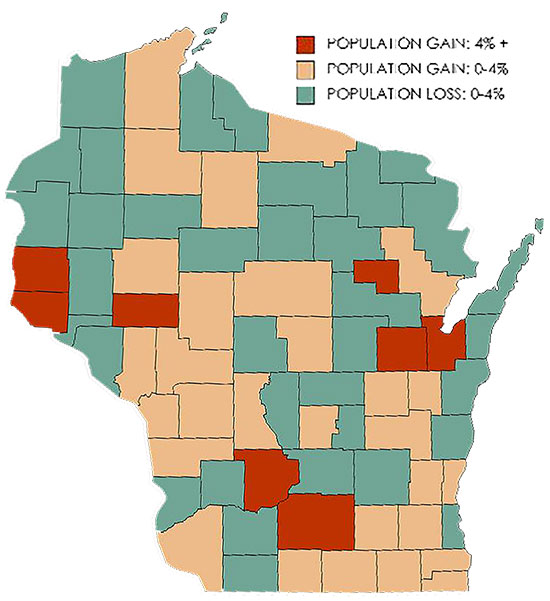

According to preliminary 2020 census data, Dane County has had the highest gain since 2010: Its population has increased by 12 percent, which will effectively entitle it to an additional Assembly seat. The Green Bay and Appleton areas and Pierce and St. Croix counties (on the western side of the state, near Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minn.) have also made significant population gains. Nearly half the state’s counties, including Milwaukee County, have lost population, although the losses have been small (4 percent or less). These shifts will add to the challenges of creating a legislative map for the coming decade. (The map is compiled from 2019 census estimates and uses a template provided courtesy of mapchart.net.)

The 2010s: Partisan Gerrymandering Takes Center Stage

The 2010 elections put a single political party, the Republicans, in charge of Wisconsin redistricting for the first time in 40 years. Legislative leaders used sophisticated statistical programs to analyze the partisan leanings of every ward, town, and village in the state and to create a map that equalized population but drew boundaries so as to maximize the number of “safe” and “likely” Republican seats. The plan worked: In 2012, Republican candidates won 49 percent of the total vote for Assembly but 60 percent of Assembly seats, and later elections produced similar gaps.15

The Republican map ran into legal challenges immediately after its enactment. Opponents claimed in a federal lawsuit that the plan violated the Voting Rights Act by improperly distributing Milwaukee-area Latinx voters to dilute their voting strength. In early 2012, a panel of three federal judges agreed and ordered modification of several districts but declined to redraw the map as a whole.16

Opponents also filed a broader lawsuit, Whitford v. Gill. They asked another federal panel to declare that because the map was a partisan gerrymander both in intent and effect it violated Democrat voters’ equal-protection, free-speech, and freedom-of-association rights under the U.S. Constitution. At that time there was little clear guidance from the U.S. Supreme Court, which had suggested at one point that partisan gerrymanders might be unconstitutional but had never settled on a workable test of constitutionality. In Vieth v. Jubilirer (2004), four justices, led by Justice Antonin Scalia, had argued that it was impossible to formulate a workable test; for that reason and because reapportionment was intertwined with political considerations, partisan gerrymandering should be deemed nonjusticiable.17

It is likely that the Wisconsin Supreme Court, ..., would treat county-line considerations as relevant but nonbinding and secondary to the population-equality imperative.

The Whitford panel divided. Two judges synthesized previous U.S. Supreme Court decisions and concluded that the U.S. Constitution prohibited any map that “(1) is intended to place a severe impediment on the effectiveness of the votes of individual citizens on the basis of their political affiliation; (2) has that effect, and (3) cannot be justified on other, legitimate legislative grounds.”18 They held that the Republicans’ map was unconstitutional under that standard.

Judge William Griesbach, the third panel member, dissented. He concluded there was no workable test for evaluating the constitutionality of gerrymanders and, therefore, the courts should not interfere.19 The U.S. Supreme Court agreed to review the case, and in 2018 it overturned the panel’s decision. The U.S. Supreme Court did not address justiciability but held instead that the Whitford plaintiffs did not have standing to assert claims of harm to voters outside their districts; to have standing as to their own district, they must show that a better map likely would have led to a different election result in that district.20

The U.S. Supreme Court sent the Whitford case back to the lower courts to give the plaintiffs a chance to make that showing. But the following year, in 2019, in Rucho v. Common Cause, the U.S. Supreme Court effectively adopted Justice Scalia’s position by a 5-4 vote: Claims based on partisan gerrymandering, for which no “limited and precise,” “judicially discernible and manageable standard” could be fashioned and that was at bottom a political question, were nonjusticiable.21 Rucho effectively foreclosed the Whitford plaintiffs’ challenge to the Republicans’ map, and their case was soon dismissed.

A Famous Reptile

The “gerrymander,” the most famous animal in the American political menagerie after the Democratic donkey and the Republican elephant, was born in Massachusetts.

In early 1812, state Democrats created several sinuous state Senate districts in hopes of preserving their majority at the upcoming election; Gov. Elbridge Gerry reluctantly signed the redistricting bill.

Elkanah Watson, a Boston artist, drew a map of one of the districts and showed it to Federalist friends at a dinner party. One joked that it looked like a salamander; another, Richard Alsop, replied: “No: a Gerry-mander!” Watson gave the new creature wings to make it complete. A Boston newspaper published his drawing and used Alsop’s new word, and within the year the term “gerrymander” was in wide use. Massachusetts Democrats held the Senate in the 1812 election, but Gerry lost his reelection bid, in part because of Watson and Alsop’s jest.

Partisan Gerrymandering’s Future

Given Wisconsin’s currently divided government and bitterly partisan political atmosphere, deadlock between the governor and the legislature over the post-2020-census redistricting and court intervention seems likely. Rucho’s constriction of federal jurisdiction over state redistricting disputes has made the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s pre-1960 gerrymandering decisions newly relevant, and a look at these decisions in the context of the post-1960 federal order may prove helpful as the new redistricting debate unfolds.

First, Whitford and Rucho have not eliminated federal courts’ role in redistricting. The U.S. Constitution still requires that legislative districts be substantially equal in population, and the Voting Rights Act still gives federal courts substantial power to shape legislative districts in high-minority-population areas such as Milwaukee. Litigants who wish to break a redistricting deadlock (or challenge an enacted plan) may seek relief in federal court if they limit their claims to population inequality and Voting Rights Act violations. In case of deadlock among state lawmakers, a federal panel would not be limited to examining districts in high-minority-population areas; it would have to redistrict the entire state. In doing so it would likely look at the multiple factors outlined in Wendelberger, including the desirability of avoiding an unduly partisan map.22

Litigants might also choose to pursue redistricting claims in the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Cunningham and other Wisconsin cases indicate that the right to equally populated districts under the Wisconsin Constitution is virtually identical to the analogous federal right.23 Despite the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s old decisions requiring deference to county lines in redistricting, Sims’ holding that population equality is paramount remains firmly in place and it is likely that the Wisconsin Supreme Court, like the Wendelberger court, would treat county-line considerations as relevant but nonbinding and secondary to the population-equality imperative.

It is an open issue whether the Wisconsin Supreme Court would entertain partisan-gerrymandering claims. Many jurists, including the dissenters in Rucho and other U.S. Supreme Court justices, have argued that partisan gerrymandering violates the U.S. Constitution’s guarantees of equal protection, free speech, and freedom of association.24 Rucho forecloses assertion of such arguments under the U.S. Constitution, but the Wisconsin Constitution contains analogous guarantees of equal protection and freedom of speech and association.25 The Wisconsin Supreme Court may, but is not obligated, to interpret those guarantees in the same manner as the U.S. Supreme Court has interpreted the federal guarantees.26 The state guarantees might be interpreted to prohibit partisan gerrymandering and to be amenable to a workable standard for evaluating an allegedly partisan plan’s constitutionality, thus making such claims justiciable in Wisconsin courts.

Old Wisconsin cases also point to other avenues that might be pursued in the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Cunningham suggests that in contrast to the U.S. Supreme Court’s holding in Whitford, individual voters may raise gerrymandering issues in state court not only as to their own district but for the state as a whole.27 And despite its frequent past reluctance to interfere with redistricting, the Wisconsin Supreme Court has repeatedly indicated that redistricting for partisan advantage is improper;28 if the task of post-2020-census redistricting ultimately falls to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, the justices surely will feel obligated to make an effort to avoid undue partisan advantage in any map that they draw. The closest thing to a safe bet for the coming redistricting process is that some or all of these issues will surface and that Wisconsin will change the contours of U.S. redistricting law once again.

» Cite this article: 94 Wis. Law. 32-37 (May 2021).

Meet Our Contributors

What was your funniest or oddest experience in a legal context?

The oddest but perhaps most interesting deposition I ever took was in a copyright lawsuit over the right to make guitars of a particular “vintage” design. We went to Berkeley, Cal., to depose a design expert who turned out to be a local music-store owner known as “Fat Dog” and a devotee of the Berkeley 1960s vibe and clothing style.

The oddest but perhaps most interesting deposition I ever took was in a copyright lawsuit over the right to make guitars of a particular “vintage” design. We went to Berkeley, Cal., to depose a design expert who turned out to be a local music-store owner known as “Fat Dog” and a devotee of the Berkeley 1960s vibe and clothing style.

Fat Dog didn’t have enough room in his store to seat us all for the deposition so he put us in his 1950s “woodie” station wagon and drove us to a campus café. Our table, consisting of three attorneys and a reporter in business dress deposing Fat Dog, got many odd looks from the students! At the end, we all looked at each other and burst out laughing at what was truly a “magical mystery tour.”

Joseph A. Ranney, Marquette University Law School, Milwaukee.

Become a contributor! Are you working on an interesting case? Have a practice tip to share? There are several ways to contribute to Wisconsin Lawyer. To discuss a topic idea, contact Managing Editor Karlé Lester at (800) 444-9404, ext. 6127, or email klester@wisbar.org. Check out our writing and submission guidelines.

Endnotes

1 Pa. Const. (1776), Frame of Government, § 17; A.Z. Reed, The Territorial Basis of Government Under The State Constitutions 138-50 (1911).

2 5 U.S. Stat. 491 (1842); Erik J. Engstrom, Partisan Gerrymandering and the Constitution of American Democracy 8-12 (2013); Elmer C. Griffith, The Rise and Development of the Gerrymander 23-118 (1907).

3 Wis. Const. (1848) art. IV, §§ 3-4.

4 State ex rel. Attorney General v. Cunningham, 81 Wis. 440, 508, 51 N.W. 724 (1892).

5 State ex rel. Lamb v. Cunningham, 83 Wis. 90, 53 N.W. 35 (1892); see Peter H. Argersinger, All Politics Are Local: Another Look at the 1890s, 8 J. of the Gilded Age & Progressive Era 7 (2009).

6 State ex rel. Bowman v. Dammann, 209 Wis. 21, 243 N.W. 481 (1932).

7 State ex rel. Martin v. Zimmerman, 249 Wis. 101, 105-06, 23 N.W.2d 610 (1946); Colegrove v. Green, 328 U.S. 549 (1946).

8 State ex rel. Broughton v. Zimmerman, 261 Wis. 398, 52 N.W.2d 903 (1952).

9 Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) (holding that redistricting issues are justiciable); Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) (strict equal-population requirement).

10 79 Stat. 437, § 2 (1965).

11 State ex rel. Reynolds v. Zimmerman, 22 Wis. 2d 544, 561-62, 126 N.W.2d 551 (1964).

12 58 Op. Atty. Gen. 88 (1969).

13 Wisconsin State AFL-CIO v. Elections Bd., 543 F. Supp. 630 (E.D. Wis. 1982); Prosser v. Elections Bd., 708 F. Supp. 859 (W.D. Wis. 1992); Baumgart v. Wendelberger, No. 01–C–0121, 02–C–0366, 2002 WL 34127471 (E.D. Wis. May 30, 2002) (unpublished).

14 Wendelberger, 2002 WL 34127471, at *3.

15 See Whitford v. Gill, 218 F. Supp. 3d 837, 846-53 (E.D. Wis. 2016).

16 Baldus v. Government Accountability Bd., 849 F. Supp. 2d 840, 854-58 (E.D. Wis. 2012).

17 See Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109, 127-29, 161-64 (1986); Vieth v. Jubilirer, 541 U.S. 267, 277-84 (2004).

18 Whitford, 218 F. Supp. 3d at 880-82, 884.

19 Id. at 932-65.

20 Whitford v. Gill, 138 S. Ct. 1916, 1928-32 (2018).

21 Rucho v. Common Cause, 139 S. Ct. 2484, 2498-2507 (2019).

22 Wendelberger, 2002 WL 341277471, at *3.

23 Compare, e.g., Cunningham, 81 Wis. at 484 and Reynolds, 22 Wis. 2d at 562, with Sims, 377 U.S. at 568-76, and Wendelberger, 2002 WL 341277471, at *2-3.

24 See, e.g., Whitford, 218 F. Supp. 3d at 880-84; Rucho, 139 S. Ct. at 2516-19 (dissent).

25 See Wis. Const. art. I, § 1 (equal protection), § 3 (free speech),

§ 4 (freedom of association).

26 See, e.g., State v. Doe, 78 Wis. 2d 161, 254 N.W.2d 210 (1977).

27 Cunningham, 81 Wis. at 508; see also Zimmerman, 249 Wis. at 111.

28 See Cunningham, 81 Wis. at 483-84, 518; Reynolds, 22 Wis. 2d at 563-64.