Wisconsin Lawyer

Wisconsin Lawyer

Vol. 80, No. 3, March 2007

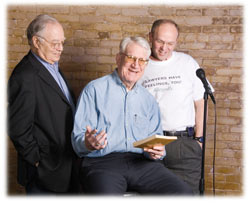

U.W. Emeritus Professor Marc Galanter, State Bar Professionalism Committee Chair Bruce Ehlke, and attorney/psychologist Gregory Van Rybroek share a light moment at Madison's Comedy Club, an appropriate location to discuss the motivation behind lawyer jokes.

ike fast food and reality television, lawyer jokes are ubiquitous in American popular culture. These jokes come in all flavors, ranging from playful to nasty, and they evoke mixed reactions from those who are the targets of the gibes.

ike fast food and reality television, lawyer jokes are ubiquitous in American popular culture. These jokes come in all flavors, ranging from playful to nasty, and they evoke mixed reactions from those who are the targets of the gibes.

Some jokes make lawyers laugh, while others might cause you to squirm, or even to seethe a bit. Just as lawyers' reactions to lawyer jokes vary, so do the possible motivations behind this brand of humor.

"Is it that people have had bad experiences with the legal system?" asks Bruce Ehlke, a Madison lawyer and chair of the State Bar's Professionalism Committee. "Is it anger? Or envy? Or is it just that lawyers are an easy target? It could be one of these factors, or none of them."

Not only is it difficult to sort out the mentality behind lawyer jokes, but humor in general "is more complicated than we think," says Gregory Van Rybroek, an attorney and psychologist who is the director at Mendota Mental Health Institute in Madison.

Van Rybroek points out that laughter, biologically speaking, is an involuntary reflex. "It's sometimes called `the luxury reflex,'" he says. "It doesn't have a real function, but we like it a lot."

Then, too, humor has its cognitive side. A joke has to have "an incongruity inside a hidden riddle," Van Rybroek explains. "In other words, you can't sort it out." As listeners, we try to figure out what's coming, but then the punch line, if it's good, catches us by surprise. We laugh because of the relief of the tension that's built up inside the joke.

A Collective Antidote

So what is it about lawyer jokes, in particular, that makes people laugh? Van Rybroek sees such jokes as a bonding experience of one group, nonlawyers, against another, lawyers. Legal situations make most people feel vulnerable or uncomfortable. Lawyer jokes allow people to externalize those feelings, as a group, against "the other."

"The public perceives lawyers as somehow being involved in personal misery of some kind," Van Rybroek says. "And misery tends to commiserate. It brings people together. You could think of jokes as a collective antidote against those considered to be the aggressors."

That points to the public's mixed expectations of lawyers, he adds. On the one hand, people want to band together against lawyers' supposed aggression. But when people have a legal dilemma, "they want a lawyer who will work the adversarial model to help and protect them," Van Rybroek points out.

Citing that same dichotomy in public attitudes is Marc Galanter, an emeritus law professor at the U.W. Law School and Centennial Professor in the Department of Law at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Galanter notes that lawyer jokes often mock lawyers as being arrogant, shifty, pushy, and so on. "In a curious way," he says, "those are the flip side of lawyers' virtues: their focus, resourcefulness, persistence."

Galanter has had a long-time interest in lawyer jokes, and he began to pay closer attention to them in the 1980s, when he was researching and writing about antilawyer sentiments. Noticing an upsurge in lawyer jokes during the 1980s, he began collecting and analyzing them. The result is his book, Lowering the Bar: Lawyer Jokes & Legal Culture, published in 2005.

In studying hundreds of lawyer jokes, Galanter noticed they tend to fall into nine clusters, which in turn comprise two broader categories: the "enduring core" (the themes that have been around for centuries) and the "new territories" (themes that have flourished since the 1980s).

The "enduring core" has five clusters, portraying lawyers as liars, economic predators, allies of the devil, fomenters of strife, and enemies of justice. Jokes in the "new territories" depict lawyers as betrayers of trust, morally deficient, objects of scorn, and targets for extinction. Falling into the last cluster are the "death wish" jokes.

Sharper Jabs

Galanter noticed that lawyer jokes took on a darker mood beginning in the 1980s, "particularly with the death-wish jokes," he says. "That kind of stuff was around before, but it was mostly racist." An example of the death-wish genre: "What do you call 6,000 lawyers at the bottom of the sea? A good start."

Epitomizing this mindset against lawyers is the 1988 publication of a book of cartoons, What to Do with a Dead Lawyer. For a time, in fact, it seemed "people were trying to outdo each other," Galanter says, in producing nastier material. "My sense is that has ebbed away now."

The past couple of decades, however, don't represent the period of the most intense animosity toward lawyers, he says. The worst period of lawyer bashing in U.S. history came after the Revolutionary War, when some state legislatures debated whether to abolish the legal profession altogether.

In Galanter's book, he also relates an anecdote about John Quincy Adams, who wrote these words to his mother in 1789 when he was a Harvard law student: "[T]he most innocent and irreproachable life cannot guard a lawyer against the hatred of his fellow citizens."

Why did lawyer bashing, and along with it lawyer jokes, hit another upswing beginning in the 1980s? It was a time that marked an increasing penetration of law into all aspects of modern life, Galanter points out.

One of the fun-spirited depictions of this trend is a New Yorker cartoon reprinted on the Web site of Meltzer, Lippe, Goldstein & Breitstone, a law firm in Mineola, N.Y. (www.mlg.com). The cartoon shows a band's guitarist on stage with his fellow musicians and a suited man holding a briefcase. The guitarist introduces them: "We've got Tom O'Brien on bass, Nick Weber on drums, and Jonah Petchesky on contracts."

Along with a growing presence of laws and regulations in people's lives has come a growing presence of and dependence on lawyers. And that spurs resentment toward lawyers, Galanter contends. He sees this situation, more than any other cause, as fueling an upsurge in lawyer jokes.

Some see lawyer jokes "as a sign that lawyers are doing something wrong," he says. "I don't think that at all. It seems to me that, in a way, lawyers are being attacked because they're doing what they're supposed to do."

The upshot is that the public isn't quite sure what to think about the legal profession. (See the accompanying sidebar, "Gauging Wisconsin Opinion About Lawyers.") "My sense is that people are ambivalent about lawyers," Galanter observes. "There's a lot of appreciation and admiration, mixed in with the hostility and resentment."

Lessons from Lawyer Jokes

If the public feels ambivalent about lawyers, it's safe to say that lawyers are just as ambivalent about lawyer jokes, coming in the wide range of tastefulness that they do.

While Galanter acknowledges that some lawyer jokes upset some of his professional colleagues, his position is that, all in all, jokes aren't a huge problem for the profession. He writes them off as "one of the costs of doing business," he says, "and lawyers have to put up with them."

His advice is that lawyers refrain from getting too distracted by jokes and instead pay heed to real problems in the profession. "There's the question of legal services for people who can't afford them," he says, "and the extent to which lawyers have lost some of their professional independence vis-à-vis their corporate clients."

Still, Galanter acknowledges that lawyer jokes "are certainly a canary in the coal mine," he says, "that tells us, yes, there is a lot of public resentment of lawyers."

And lawyers shouldn't let themselves completely off the hook, either, some would argue. Sure, lawyer jokes, like all jokes, are based on stereotypes, exaggerations, and distortions, says Van Rybroek. But lawyers must bear in mind that these stereotyped images "usually have some tendrils of truth in them," he says, emphasizing that those words are coming from someone who is himself a lawyer. Can any lawyer, after all, say he or she never met an attorney who was arrogant or greedy or conniving?

As Van Rybroek sees it, lawyer jokes depict a caricature of lawyers, distorting certain traits, just as a caricature drawing of Jay Leno portrays him with a much-enlarged chin. "If lawyers are going to better understand lawyer jokes," he says, "then they have to deal with the self-examination of their caricature."

Jokes with a Purpose

Echoing the call for self-examination is Charles McCallum, a Grand Rapids, Mich., attorney and chair-elect of the American Bar Association's Business Law Section. At the section's annual meeting last August, it presented a program, "Lawyer Jokes and Bashing - a Bum Rap or Painfully on Target?" There McCallum presented a paper, "Professionalism: It's No Joke," that later hit print in the January/February 2007 issue of Business Law Today.

McCallum says that, in his 43 years in practice, he's "never been terribly bothered" by lawyer jokes. Nor does he see them as "a national vendetta against lawyers." Still, he adds, "Maybe we ought to think a little more about what lawyer jokes mean." He notes, for instance, that in the Enron scandal and other ethics disasters of recent years, some lawyers behaved badly, as jokes portray lawyers behaving in general.

As for what the profession ought to do about lawyer jokes, "I think, in the first place, you restate the missing premise - that we are professionals," McCallum says. "There is something to professionalism. It has duties and obligations and rules of conduct."

McCallum would like to see, for instance, more lawyers volunteering in their communities. "Not just going to the parties to meet the rich folk," he emphasizes, "but actually working in the community."

One obstacle he cites is the pressures in law practice today - pressures that sometimes push firms to discourage their attorneys from spending time on outside activities. "That has to stop," McCallum says. "Working for your community is part of the job."

He also calls for open discussion in the profession about concepts such as honesty and integrity. These aren't merely old-fashioned notions, McCallum emphasizes. "I think sometimes we get cynical or embarrassed about saying that honesty and integrity are important values," he says. "But they are, and we shouldn't feel embarrassed about saying so." That goes for law schools, too, he adds, where there should be ample discussion about lawyers' special professional obligations.

Thus, in McCallum's view, lawyer jokes serve a purpose for lawyers. "I think they're useful to make us recommit to professionalism," he says.

And while lawyer jokes, even the most mean-spirited ones, may never disappear from our pop culture scene, maybe, as lawyers recommit to professionalism, those jokes will lose some of their sting. But, McCallum stresses, changing the public view isn't the crucial point.

"What we want to change," he says, "are our own attitudes and perceptions. What's important is not that we try to prove anything to anybody, except to ourselves. It's to your own self be true."

Wisconsin Lawyer