Statehood arrived in Wisconsin in 1848, but it was not until 1926 that the U.S. Supreme Court settled the border with Michigan. Wisconsin prevailed in that action.[1] A century later, it is worth revisiting the origins of the case and the case itself – as both an interesting part of state history and an illustration of the challenging nature of boundary controversies.

“Boundary disputes,” observed Wisconsin historian Louis P. Kellogg, “have ever constituted a fruitful source of contention between men and nations.”[2] Kellogg’s remark was a generalized thought in the narrower context of the disputed Michigan-Wisconsin boundary, but the notion is familiar to practicing attorneys. Boundary disputes are common: between private property owners, local governments, states, or nations. Often the problem arises from erroneous descriptions or surveys. But the resolution of such disputes does not necessarily turn on technical matters – other factors may come into play.

Antecedents to the Dispute

At the conclusion of the French and Indian War (1754-63), France ceded to England the land between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, which later became known as the Northwest Territory. In 1784, Thomas Jefferson issued a report to the Confederation Congress (this being before the adoption of the U.S. Constitution) in which he proposed that the new government eventually divide the region into states.

In 1787, the Confederation Congress enacted the Northwest Ordinance.[3] The law authorized the establishment of three to five states in the Northwest Territory and described the terms of territorial administration and the requirements for state formation.

Congress admitted Ohio into the Union in 1803. There was a problem. The Northwest Ordinance described the southern border of what became Michigan. The line ran from the southernmost point of Lake Michigan due east to Lake Erie.[4] Depending on the land survey, the mouth of the Maumee River and the future city of Toledo might turn out to be not in Ohio. Ohio attempted to overcome the problem by describing a different border in its congressionally approved constitution, the easterly point of which met Lake Erie just north of Toledo (the “most northerly cape of the Miami [Maumee] Bay, after intersecting the due north line from the mouth of the Great Miami [Maumee] River…”).[5] The southern boundary of the Michigan Territory, established in 1805, described a line consistent with that prescribed in the Northwest Ordinance – putting Toledo in Michigan.[6] Michigan refused to relinquish jurisdiction of what became known as the Toledo Strip.

The matter came to a head in 1835 when Michigan made its bid for statehood. Ohio and Michigan dispatched their militias to the Strip. Confrontation, arrests, a stabbing, and much saber rattling ensued. Congress, siding with Ohio, was content to hold hostage Michigan statehood until Michigan agreed to the “corrected” boundary.[7]

As a sweetener, Congress offered Michigan the “western” upper peninsula – three quarters of the upper peninsula land mass that seemed to belong to what would become Wisconsin.[8] Michigan accepted.

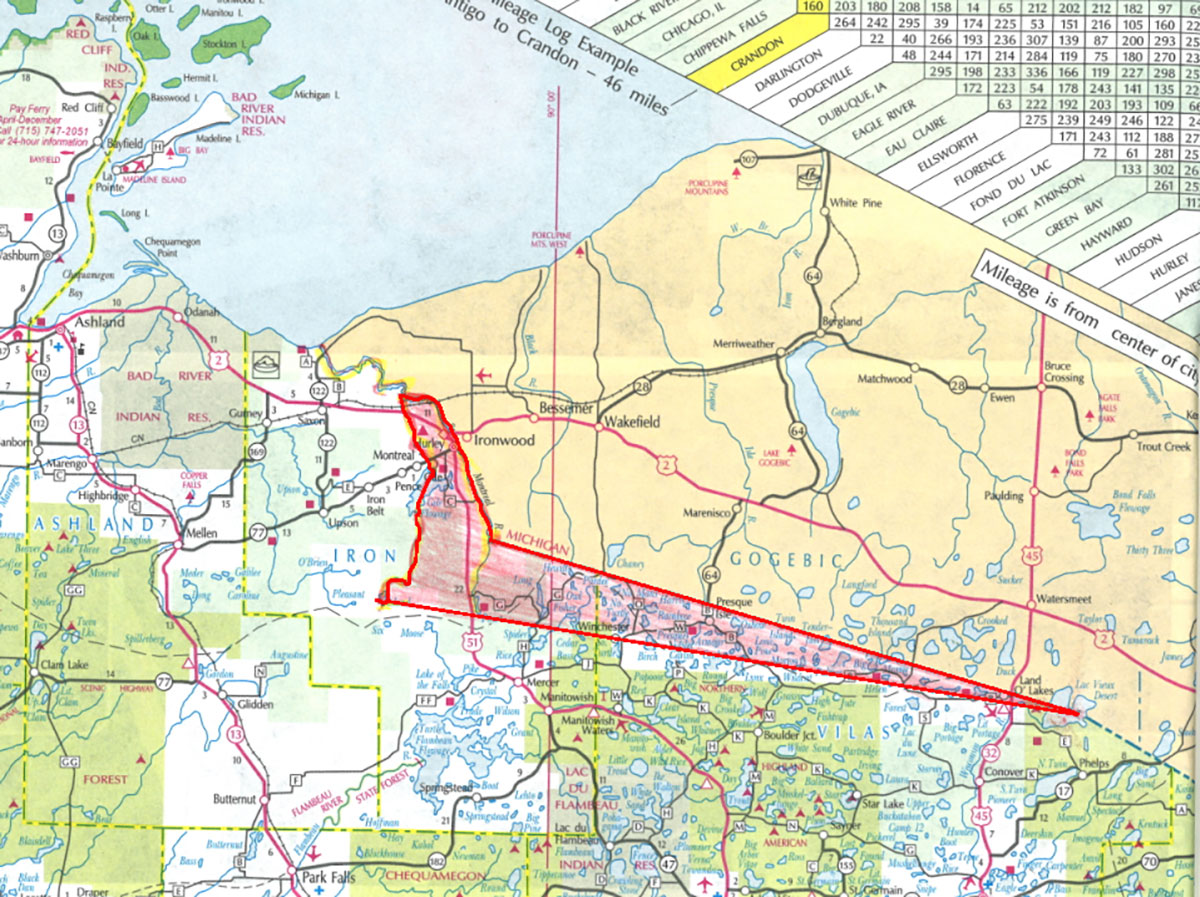

The Wisconsin Wedge map. According to Michigan, the disputed Wisconsin Wedge – about 235,000 acres – and part of the iron-rich Gogebic Range, belonged to Michigan. Wisconsin Historical Society, used with permission.

The Survey

Wisconsin gained territorial status in 1836. In that year, Congress adopted an act that described the Wisconsin-Michigan boundary with the Montreal, Brule, and Menominee Rivers as the boundaries. The Montreal River flows into Lake Superior. The Brule River is the principal tributary of the Menominee River. The Menominee River flows into Green Bay.

The Montreal River was thought to originate at Lac Vieux Desert (Lake of the Desert). The Brule River headwater was unknown, so the description read “to the head of said river nearest to the Lake of the Desert.”

As such, the map and the resulting boundary description presumed a nearly continuous waterway separating the two states.

Efforts to survey this border languished until the War Department’s Bureau of Topographical Engineers assumed responsibility. The bureau assigned the surveying task to Captain Thomas Jefferson Cram, a West Point-educated officer. His counterpart was Douglass Houghton, a physician, scientist, and Michigan’s first state geologist.[9]

In 1840, Cram and Houghton led the boundary survey team up the Menominee River and fixed the Brule River’s source at Brule Lake. To the northwest at Sandy Lake, about 8 miles from Lac Vieux Desert, the Chippewa (Ojibwe) appeared, told the team it was encroaching on its territory, insisted the team “could be allowed to go no farther towards the setting of the sun into the Ka-ta-kit-te-kon (Chippewa) country,” and told the team to turn back.[10] Chief Ca-sha-o-sha arrived the next day. Through amiable negotiation, Cram purchased for “presents” a right-of-way through Chippewa country to the Montreal River. All future surveyors were also to provide such gifts for passage. The parties memorialized this “treaty” on a piece of birchbark.

Cram and Houghton determined that Lac Vieux Desert was not the source of the Montreal River but of the Wisconsin River.[11] From Lac Vieux Desert, however, Cram and Houghton could not continue “on account of having reached a point beyond which the description of the boundary ceases to be in accordance with the physical character of the country.”[12]

The survey team returned to the Upper Peninsula in 1841. Cram identified the Montreal River’s east channel as the “main channel” and fixed its headwaters at the junction of “two inconsiderable streams not more than 20 to 30 feet wide called Balsam and Pine Rivers.” Cram designated this point astronomical station no. 2: it marked the western end of the straight line measured from Lac Vieux Desert.[13]

Wisconsin’s impending statehood occasioned an updated survey. In April 1847, the Government Land Office hired William A. Burt for the task. Burt and his party met the Chippewa at the headwaters of Brule River (the location marking the eastern point of the land border between Wisconsin and Michigan). The Chippewa brought with them the 1840 birchbark treaty.

A change of circumstance had intervened. In 1842, the U.S. had acquired this territory – in fact much of northern Wisconsin and the western Upper Peninsula – in the Treaty of La Pointe, but this Chippewa band appeared unaware. Not to delay matters, Burt again “made treaty” and presented gifts of tobacco and other supplies. A tamarack tree blaze marked the spot. (The “Treaty Tree” has not survived – it has been replaced by a historical marker and stone boundary monument.) Burt’s border survey ratified the Cram-Houghton survey, including its designation of the junction of the Pine and Balsam Rivers as the border terminus on the Montreal River.

The Cram-Houghton tree blaze memorialized a “treaty” to allow a boundary survey team right-of-way through Chippewa country to the Montreal River. It is the piece of a birch tree, originally on the shore of Trout Lake in Vilas County, about 10 miles north of Minocqua, on which Cram and Houghton scratched out a surveyor’s mark (blaze). It bears their names and the date “Aug 11, 1841.” Wisconsin Historical Society, museum object number 1977.97, used with permission.

The Boundary Described

Wisconsin’s 1848 Constitution mirrored the boundary established by Cram and Houghton and confirmed by Burt:

“From the ‘mouth of the Menominee River; thence up a channel of said river Brule River; thence up said last-mentioned river to Lake Brule; thence along the southern shore of Lake Brule in a direct line to the center of the channel between middle and south islands, in the Lake of the Desert; thence in a direct line to the headwaters of the Montreal River, as marked upon the survey made by Captain Cramm; thence down the main channel of the Montreal River to the middle of Lake Superior….’”[14]

The Dispute

But all was not settled. Michigan did not abandon the notion that Cram had incorrectly determined the headwaters of the Montreal River. The Montreal River forks into a western and eastern branch about 18 miles from its mouth. Given that both branches were of relatively equal depth, which one was the river? Cram had surveyed along the eastern branch. Michigan maintained the western branch was the main channel with its headwaters at Island Lake.

According to Michigan, the disputed Wisconsin Wedge – about 235,000 acres – belonged to Michigan. This land was part of the Gogebic Range – by then recognized as a significant iron-mining region and a forest-rich area ripe for timber production.

Despite the uncertainty, Wisconsin continued to administer its boundaries as fixed by the Montreal’s eastern branch, including what became the city of Hurley and the town of Presque Isle.

There the matter rested until Michigan adopted a new constitution in 1908. That document described the border consistent with Michigan’s original position: a boundary that would follow “the westerly branch of the Montreal River.”

The dispute, dormant for so long, was joined. Michigan sent representatives to Wisconsin to propose a joint commission for the adjudication of the boundary but could not interest state officials. As far as Wisconsin was concerned, the eastern branch of the Montreal River as surveyed by Cram was the true border.

The Burt treaty tree marked the spot where William Burt “made treaty” with some Ojibwe Tribe members in 1847. The tamarack tree no longer exists. Burt’s border survey ratified the Cram-Houghton survey. Wisconsin Historical Society, WHIW014F4F, used with permission.

The Dispute Reaches the U.S. Supreme Court

In 1923, to settle the matter, Michigan filed an original-jurisdiction action[15] before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court’s roster included some particularly famous members: William Howard Taft, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Louis Brandeis, and Harlan Fiske Stone. Taft assigned the opinion to Justice George Sutherland who, on March 1, 1926, delivered the unanimous opinion of the Court.[16]

The Court concluded that Congress understood the east branch to be the upper portion of the Montreal River. The Court, however, declined to base its holding on this finding. Rather, the Court observed that when admitted to statehood, Wisconsin possessed the area, and the state continued to be in possession of the area in dispute and had exercised dominion over it. “That rights of the character here claimed,” stated the Court, “may be acquired on the one hand, and lost on the other, by open, long-continued, and uninterrupted possession of territory, is a doctrine not confined to individuals, but applicable to sovereign nations as well…. That rule is applicable here, and is decisive of the question in respect of the Montreal river section of the boundary in favor of Wisconsin.”[17]

-1200.jpg)

Border survey 1928 mile zero marker. Photo: Bill Kralovec, used with permission.

Conclusion

In the end, Michigan’s evidence did not carry the day. The decision turned not on technical issues – the accuracy of survey or description – but on pragmatic principles akin to laches and reliance.

Finally, there is the question of whether Michigan fully accepted the decision. Some doubt exists. The historical record reflects that in 1963 Michigan again adopted a new constitution. The document omitted a boundary description.

Endnotes

1 Michigan v. Wisconsin, 270 U.S. 295 (1926).

2 Louis Kellogg, The Disputed Michigan-Wisconsin Boundary, Wis. Mag. of Hist., vol. 1, no. 3 (March 1918).

3 An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, 1 Stat. 50 (1787).

4 Id art. 5.

5 Ohio Const. of 1802, art. VII.

6 Act to Divide the Indiana Territory into Two Separate Governments, ch. 5, sec. 1, 2 Stat. 309 (1805).

7 Evan Andrews, The Toledo War: When Michigan and Ohio Nearly Came to Blows, Hist. (Nov. 21, 2016).

8 Michigan, initially considered the loser in the bargain, turned out to be the winner. According to secondary sources, a report once described the Upper Peninsula as a sterile region on the shores of Lake Superior destined by soil and climate to remain forever a wilderness. That changed in the 1840s. Explorers discovered rich mineral deposits (primarily copper and iron). Upper Peninsula mines produced more mineral wealth than the California Gold Rush. The Upper Peninsula supplied 90% of America’s copper by the 1860s. It was the nation’s largest supplier of iron ore by the 1890s. Logging also became an important industry.

9 Houghton, Mich., bears his name. Houghton died in 1845 at age 36 when his party’s small boat capsized during a Keweenaw peninsula expedition.

10 See 1841 Report app., infra note 12.

11 During the 1841 expedition, Cram and Houghton detoured south to explore the upper tributaries of the Wisconsin and Chippewa Rivers and the forests, lakes, and streams in the area. On the shore of Trout Lake in Vilas County, about 10 miles north of Minocqua, they scratched out a surveyor’s mark, or blaze, on a tree. It bears their names and the date: “Aug 11, 1841”. Cram designated the spot as “astronomical station no. 3.” It likely had a clear view of the sky, which was essential for sextant readings – the only reliable way to establish latitude. Loggers eventually felled the tree but preserved the blaze. It is in the collection of the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison.

12 Captain Cram’s reports were printed in U.S. Senate, Message from the President of the United States, in Compliance with a Resolution of the Senate in Relation to the Survey to Ascertain and Designate the Boundary-Line Between the State of Michigan and the Territory of Wiskonsin, S. Doc. No. 151, 26th Cong., 2d Sess. (1841) [hereinafter 1841 Report]; and U.S. Senate, Report of the Secretary of War: Communicating, in Compliance with a Resolution of the Senate, a Copy of the Report of the Survey of the Boundary Between the State of Michigan and the Territory of Wisconsin, S. Doc. No. 170, 27th Cong., 2d Sess. (1842). See also Lawrence Martin, The Michigan-Wisconsin Boundary Case in the Supreme Court of the United States, 1923-26, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Sept. 1930).

13 Often translated as Lake of the Desert. According to Cram, in “mongrel” French it meant “old potatoe-planting ground.” See 1841 Report app., supra note 12.

14 In this document, Cram acquired an extra “m.”

15 U.S. Const. art. III, § 2, cl. 2.

16 Michigan v. Wisconsin, 270 U.S. 295 (1926). Later in the year, the Court issued a decree describing the new boundary. This description referenced the 1847 Burt survey. Michigan v. Wisconsin, 272 U.S. 398 (1926). In connection with the Brule and Menominee Rivers sections of the boundary, the Court confirmed Wisconsin’s claim to the river islands below the Quinnesec Falls. In connection with the Green Bay section of the boundary, the Court confirmed Wisconsin’s claim to Washington, Detroit, Rock, Plum, and Chambers Islands. Several years later in connection with the boundary at the mouth of the Menominee River and the boundary extension into Green Bay, the Court adjusted the border yet again. Wisconsin v. Michigan, 295 U.S. 455 (1935); Wisconsin v. Michigan, 297 U.S. 547 (1936).

17 Michigan v. Wisconsin, 270 U.S. at 308.

» Cite this article: 99 Wis. Law. 12-16 (February 2026).