|

Guest Editorial

Miranda

challenged in federal criminal cases

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit recently

held that 18 USCS section 3501 - and not Miranda -

governs the admissibility of confessions in federal court. The

decision has been appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and if

it is sustained, the protection the Miranda warning has provided

for more than 30 years, particularly to the poor and uneducated,

will be drastically reduced.

By Robert W. Landry

On Feb. 8, 1999, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit, by a vote of two judges to one, ruled that the 33-year-old

Miranda

case was passé and its famous rubric no longer was required

to admit in evidence a defendant's confession in a federal

criminal case. This decision has dubious precedential merit,

but if it is sustained on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, the

protection the Miranda warning has provided for more than

three decades, particularly to the poor and uneducated, will

be drastically reduced. In addition, there would be a return

to the free-for-all courtroom battles so common in pre-Miranda

trials regarding due process, Fifth Amendment rights, and equal

protection in confession contests.

The Virginia appeals court said, "[W]e hold that Congress,

pursuant to the power to establish rules of evidence and procedure

in the federal courts, acted well within its authority in enacting

18

USCS sec. 3501. As a consequence, sec. 3501 rather than Miranda,

governs the admissibility of confessions in federal court."1

Dickerson was charged with conspiracy, four counts of bank

robbery, and three counts of using a firearm in relation to a

crime of violence. Dickerson filed motions in the trial court

to suppress certain statements, which were granted based on Miranda.

The trial court held that the statements could not be used in

the government's case in chief because the Miranda

warning was not timely given but ruled that they could be used

for impeachment purposes, on the grounds that Dickerson had been

accorded due process in the course of his interrogation by law

enforcement officers.

After the government's motion to reconsider the admissibility

of Dickerson's confession was denied by the trial court,

the government appealed, arguing before the Federal Court of

Appeals that the trial court abused its discretion. The government

offered to prove that Dickerson received a Miranda warning

prior to giving the statements in the form of written documents

signed by Dickerson acknowledging that he was timely warned.

Because the government failed to offer this evidence when the

motion to suppress was first heard, the trial court refused to

change its original order to suppress. 18

USCS section 3501 was not presented or argued.

The government appealed the order denying the motion to reconsider.

The court of appeals reversed the trial court remanding the case

with instructions to admit the confession. It said the confession

was admissible under section 3501, which replaced Miranda.

Precedential effect

On appeal, neither the government nor Dickerson relied upon

section 3501. It was not briefed by them nor was it argued. An

amicus brief was filed by the Washington

Legal Foundation: Safe Streets Coalition arguing that section

3501 replaced Miranda. A majority of the court agreed.

It remanded the case to the trial court with instructions to

allow the disputed statements of Dickerson in evidence.

In his dissent, Circuit Judge Michael said, "We perform

our role as neutral abettors best when we let the parties raise

the issues and both sides brief and argue them fully." And,

"It is sound judicial practice for us to avoid issues not

raised by the parties." In further support of his dissent

he cites Davis v. United States: "This is not the

first case in which the United States had declined to invoke

sec. 3501 before us - nor even the first case in which the

failure has been called to our attention."2

It is unusual for a case to be decided on a theory of law

that is not argued by the parties. The strength of the American

justice system depends to a large degree on its adversarial nature

where disputes are resolved by an intellectual battle between

conflicting points of view. Arguments on one side are balanced

with arguments on the other with a reasonable expectation that

the court will then be able to make a well-considered decision.

This was not done in the Dickerson appeal. Neither side presented

briefs or argument on one side or the other. On such an important

issue as discarding Miranda, it is difficult to justify

the appeal court's impetuosity. It puts the precedential

effect of the decision in peril.

The Miranda decision

On June 13, 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down the momentous

case of Miranda

v. Arizona.3 Some predicted terrible

and disastrous consequences, and a collapse of our criminal justice

system. Others cautiously hoped that it would produce a major

improvement by setting a yardstick for determining due process

and voluntariness when judging admissibility of confessions.

After 33 years of use throughout the United States the debate

continues, and each person is free to judge the historic consequences.

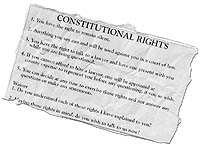

Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the majority opinion in Miranda.

He said, "As for the procedural safeguards to be employed,

unless other fully effective means are devised to inform accused

persons of their right of silence and to assure a continuous

opportunity to exercise it, the following measures are required.

Prior to any questioning, the person must be warned that he has

a right to remain silent, that any statement he does make may

be used as evidence against him, and that he has a right to the

presence of an attorney, either retained or appointed. The defendant

may waive effectuation of these rights, provided the waiver is

made voluntarily, knowingly and intelligently."

The privilege against self-incrimination, an essential mainstay

of the American adversary system, has its constitutional foundation

in the respect a government, state or federal, must accord to

the dignity and integrity of its citizens. The poor, the uneducated,

the inexperienced, and minorities are particularly vulnerable

to interrogation tactics of law enforcement officers. It may

not be presumed that they know their rights, nor is circumstantial

evidence sufficient to constitute a waiver of their rights. They

are easier targets to extract confessions from than the rich,

intelligent, experienced, and powerful. Some will argue that

that is okay. The Supreme Court did not think so, and prescribed

the warning that we now take for granted. The warning, of course,

does not make a confession admissible automatically. The defendant

must freely, voluntarily, and intelligently waive his or her

right to remain silent. That subjective test is made after there

is sufficient evidence that the warning was properly given. With

a few exceptions, the warning requirement works well, and the

prediction that confessions would dry up as a consequence has

not happened.

Effect of Miranda at trial

In spite of the warning given to an accused required under

Miranda, confessions continue to be used in the prosecution

of criminal cases. Surprisingly, the number of confessions has

not perceptibly changed, but the ease with which the issues pertaining

to them has. A judicial hearing out of the presence of the jury

is conducted to determine whether or not the confession may be

admitted in evidence. If it is allowed in evidence, the case

before the jury proceeds including testimony surrounding the

confession. The defendant may challenge the weight to be given

to the confession - as is the case with all evidence. However,

the trial pattern is completely different from pre-Miranda

trials.

In pre-Miranda trials the issue of voluntariness of

the confession frequently became the main issue in the case.

The government was placed on the defensive, and the accusatory

claims of the defendant about the misconduct of the officers

became more important than the charges against the accused. Even

when there was little or no defense offered, the trial would

be extended because the defendant would raise the specter of

a coerced confession and change the focus of the trial to misconduct

on the part of law enforcement - sometimes with good reason.

Under Miranda, those issues are decided in a motion

before the court on whether the warning was properly and timely

given and whether there was a free and intelligent waiver of

the defendant's rights. This explicit standard gives notice

to law enforcement exactly what it has to do to meet constitutional

requirements. Prior to Miranda even judges were in doubt

about those requirements. So, for the first time in American

judicial history, a uniform standard was established on the admissibility

of confessions. More uniform application of the law (equal protection),

more orderly and efficient administration of justice, and a better

focus on the substantive issues at trial are all benefits that

the court system has enjoyed because of Miranda, without

compromising either the rights of the accused or the best interests

of the public.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I believe that Miranda is good law for

the following reasons:

- It accomplishes the purposes for which it was intended -

to protect the individual against the powers of the state in

accordance with the U.S. Constitution;

- It is accepted by sheriffs and police as a workable and reasonable

guideline that does not compromise the effectiveness of law enforcement;

- Criminal trials are conducted with greater integrity and

efficiency due to the sanitizing effect of Miranda; and

- The Dickerson case fails to weigh in as reliable precedentiaal

authority for substituting 18 USCS section 3501 (1998) for Miranda

v. Arizona.

The fate of this case will be exciting to follow because it

may forecast the posture of the U.S. Supreme Court relative to

other Warren Court decisions. If review is accepted and the decision

is affirmed, its effect may be postponed because it is the policy

of the Department of Justice not to substitute the federal statute

for Miranda and it is unlikely that Attorney General Janet

Reno will change that policy in spite of affirmation.

It is ominous that a high federal court would take an uncharacteristic

prosecutorial role in an opinion that undermines a long-standing

constitutional protection in the guise of enlightened public

interest and scholarship. If decisions such as this go unnoticed,

no one can predict what mischief they may cause. Vigilance and

assertiveness are essential to protect the legal system from

erosion whether by judges with personal agendas or by persons

with special interests.

Endnotes

1 United

States v. Dickerson, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth

District, No. 97-4750 (1999).

2 Davis

v. United States, 512 U.S. 452 (1994) at 463.

3 Miranda

v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

Robert W. Landry, U.W. 1949, is a retired

Wisconsin circuit court judge, having served on the trial bench

in Milwaukee for 40 years. He participated in the transition

from pre- to post-Miranda.

|