Following in the Family Footsteps

Devotion to the practice of law runs through multiple generations of

these Wisconsin families.

By Karen Bankston

Science has yet to identify an attorney gene, but a genetic

predisposition for the law seems to run through several Wisconsin

families.

The hereditary link to the law is so strong that some families have

not one, but two or three attorneys in each generation. Some of these

third, fourth, even fifth generation attorneys have lawyer genes on

several branches of their family tree.

For example, the maternal grandfather of attorney siblings Virginia

R. and Daniel Finn was a Philadelphia lawyer, and their paternal

grandmother had three attorney brothers. Their father and mother, J.

Jerome and C. Virginia Finn, are both alumnae of Marquette University

Law School, their father "in the '50s (class of 1958)" and

their mother "in her 50s (class of 1989)," reports Virginia, an

attorney with Michael, Best & Friedrich LLP.

"If our family has any expectation of the law, it is that it will

keep your mind active. Our family values include the Irish love of a

good argument for argument's sake," she adds. "Perhaps we had to be

attorneys for that reason alone."

Thus, the flip side in the nature versus nurture debate wields some

influence. A nearly universal childhood experience among the sons and

daughters of attorneys was spending Saturday mornings at the law office,

though few report that those hours gave them clear insight into the

practice of law.

"I really didn't have any concept of what he did at work," admits

Joseph Tierney IV. "I guess I would have said, 'My father reads

books.'"

These families' professional heritage left vastly different

impressions on younger generations. Rebecca Wickhem Wegner's high school

teachers collected lawyer jokes she could take home to her father. John

O'Melia Jr. remembers attorneys from around the state descending on the

family deer camp each November. Whenever Thomas Drought's family

traveled across the state, they stopped for meals only at restaurants

belonging to the association his father represented. All in all, these

must be good memories because the proud tradition continues in these and

other families across the state.

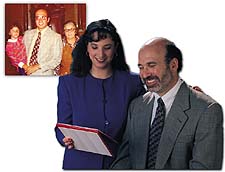

Legacy of Law: The Smolers

Harriet Stern Smoler, right, the 78th women admitted to

practice in Wisconsin, proudly appears before the Wisconsin Supreme

Court in 1975 to move her son, Bill's, admission to the bar. Bill holds

daughter Tedia, who was admitted to practice 23 years later. Below: Bill

and Tedia recently took a moment to admire Harriet's law school diploma,

which now graces Tedia's office.

Harriet Stern Smoler may not have practiced law for long, but her

love for the profession is reflected in the career choices of her son

and three of her 10 grandchildren.

The newest lawyer in the family, Tedia Smoler, stopped often on her

way to and from the U.W. Law Library to find her grandmother (Class of

'29) and father (Class of '75) in their class pictures. Harriet Smoler's

law school diploma hangs in Tedia's office at the Waukesha County Public

Defender's Office.

After Harriet Stern graduated from law school, she had her own

practice for a short time and worked with the Kenosha Social Services

Department early in the Depression, says her son Bill Smoler. After she

married Fred Smoler, Harriet switched careers to help operate the family

retail business.

Bill believes his mother's passion for the law was manifest in the

tradition of gathering to watch "Meet the Press" and then adjourning for

a Sunday brunch that often stretched over one or two hours as the family

debated political issues of the day. "My mother led those discussions in

a way that was not dissimilar to what I experienced years later in law

school," he recalls.

Harriet appeared before the Wisconsin Supreme Court in 1975 to move

her son's admission to the Bar. "I believe that was one of her proudest

moments," says Bill, an attorney with Murphy & Desmond, Madison.

Harriet died in May 1997, a year before Bill's daughter graduated from

their alma mater. Harriet is one of Wisconsin's first 150 women lawyers

who will be honored by the State Bar at a reception in Madison in

October. (Please see the "President's Perspective" at page 5 for more

information.)

Ask Tedia why she chose a law career, and she may say it comes down

to the difference between her scores on entrance exams for law school

and the psychology graduate school program.

"But my mother says she always knew I'd be a lawyer," Tedia says

ruefully. "She also always said that I like to argue, which I used to

think was a criticism."

Tied to History: The Droughts

The lawyers of the Drought family are linked with the history of

Wisconsin's highways, restaurants, and lumberyards.

James Drought was the executive director, secretary, and attorney for

the Milwaukee Automobile Club and played a major role in the development

of the state's automobile industry. In 1926 he joined his son, Ralph,

just out of the U.W. Law School, to form Drought & Drought. Father

and son practiced together until James retired in 1943. Ralph had a

general practice, and his two principal lobbying clients were the

Wisconsin Restaurant Association and Wisconsin Retail Lumbermen

Association.

"I remember that whenever my family traveled around the state, we

could only eat in restaurants that were part of the restaurant

association, and we were always stopping to visit lumberyards," says

Ralph's son, Thomas.

Unlike his grandfather and father, Thomas never had an opportunity to

practice with his father, who died in 1957 while Thomas was still in law

school. Thomas practices with Cook & Franke, which started out as

Drought & Drought.

He sees many contrasts between the family law practice of his

childhood where photocopies hung from clothespins to dry and typewriters

clacked away in outer offices. "My grandfather and father had a true

general practice," he notes. "Back then there was no such thing as

environmental law, telecommunications law, employment law. People didn't

'specialize' in aircraft litigation or sports law."

Two of Thomas's children represent the fourth generation of Drought

lawyers. Kay Drought is director of the Legal Aid Society in Portsmouth,

N.H. Her sister Ellen was honored this spring as one of two

fourth-generation graduates from the U.W. Law School.

Ellen taught English in Japan, studied journalism, and considered

pursuing a Ph.D. in history before applying for law school. "Although I

enjoyed studying history, I wasn't passionate enough to pursue it," says

Ellen, who will join the securities team at Godfrey & Kahn,

Milwaukee. "A law degree is more versatile. In this day and age, lawyers

do lots of different things."

Triple Tradition: The Affeldts

The Affeldt Law Offices S.C., West Allis, includes three brothers,

David, Steven, and John, whose father, maternal uncle, and grandfathers

on both sides of the family were attorneys. It seems a foregone

conclusion that this third generation would take to the law. On the

other hand, the three partners are the youngest of seven children; their

older siblings chose other career paths.

"I don't think any of us felt as if we were pushed into law," John

says, although the brothers agree that once they decided to become

attorneys, none of them considered any other path than joining the

family firm begun by their grandfather, George A. Affeldt, in 1909.

The Affeldt brothers have a general civil practice in the tradition

of their grandfather and father, George R. Their maternal grandfather,

Louis J. Fellenz, served as district attorney and circuit court judge in

Fond du Lac County and as a state senator. His son, Louis J. Fellenz

Jr., also was a state senator and later worked for the Federal Housing

Authority.

Growing up in a big family was good preparation for practicing law

together, Steven says. "We learned early to get along and share because

we had to."

They remember childhood trips to their father's law office and orders

to be quiet whenever clients stopped by to consult George Affeldt in his

study at home. "We may not have understood totally what dad did as a

lawyer, but we always knew the amount of time, effort, and education

required to do the job well," Steven says.

Moses Hooper works at his desk in the Hooper Building (now called the

Algoma Building) at 110 Algoma Blvd. in Oshkosh. At one time, Moses was

the oldest practicing lawyer in the U.S. and the oldest attorney to

argue before the U.S. Supreme Court (at age 93). Edward F. Hooper

(seated at left) represents the family's fourth generation of lawyers.

He practices estate planning in Appleton. Kellett Koch (far right),

representing the fifth generation, recalls that his

great-great-grand-father's career was "a source of great pride in our

family."

Just as law has become a tradition in their family, engaging the

services of the Affeldt Law Offices is an institution for many families

in their hometown. "We have multiple generations of clients to go with

our multiple generations of lawyers," Steven notes. "We still work with

some clients who remember my grandfather coming to their house, and he's

been dead for 45 years."

Following Moses: The Hoopers

Moses Hooper attended Yale University Law School and then came to

Wisconsin in 1857. He settled first in Neenah and later in Oshkosh where

his private practice flourished. Moses was Kimberly-Clark's first

corporate counsel, a post he held until he retired in 1930 after 74

years in the law. At one time, he was the oldest practicing lawyer in

the United States and the oldest attorney to argue before the U.S.

Supreme Court (at age 93). He died in 1932 at age 97.

Moses was joined in his practice by sons Ben and Edward M., who

succeeded his father as Kimberly-Clark's corporate lawyer. William S.

Hooper, Edward's son and Moses' grandson, represents the third

generation of Hooper attorneys. The Hooper family didn't have a lawyer

in the fourth generation until Edward F. Hooper took an early retirement

from his work as a senior systems engineer with IBM to go to law

school.

"I had to fill in for the fourth generation at the last moment. It

finally caught up with me," says the Appleton attorney who concentrates

in estate planning. "In fact, the fifth generation in our family was

admitted to the bar before the fourth."

Kellett Koch, the fifth-generation Hooper family attorney, recalls

that his great-great-grandfather's career was "a source of great pride

in our family." But it was his grandfather, a chemical engineer who

chaired the Kellett Commission to reorganize state government, who

influenced Koch to become an attorney. Koch practices with Koch &

McCann in Milwaukee.

Trial's End: The Wickhems

On the eve of her law school finals, Rebecca Wegner recalls that her

proud father sent her a package filled with memorials full of accolades

for the first three generations of lawyers in her family.

"It terrified me," she confesses with a laugh. "I called him up and

said, 'What are you trying to do to me with all these tributes for what

my family has accomplished?'"

James G. Wickhem, the son of Irish immigrants, began his law practice

in Beloit in 1882, and his son, John D. Wickhem, was a U.W. law

professor who became a Wisconsin Supreme Court justice. The third

generation was represented by John C. Wickhem, a trial lawyer for almost

40 years, who served as president of the State Bar. His wife, Mary, took

a year of law school and served on the Board of Bar Examiners and

several State Bar committees. Mary's father, John Boyle, was U.S.

attorney for Wisconsin's western district, and her brother, John J.

Boyle, was a Janesville attorney who served as a Rock County circuit

judge.

James D. Wickhem practiced with his father as an associate, partner,

and finally as cocounsel until John's death in 1987. "My dad and I were

partners, and he used to kid that his legal education had been repealed

and recreated at least twice in his career," recalls James, a partner

with Meier, Wickhem, Southworth & Lyons, Janesville.

The fifth generation includes James Scot Wickhem, a patent law

specialist with Michael, Best & Friedrich LLP, Milwaukee, and

Rebecca, who recently began her law career at Foley & Lardner in

Milwaukee.

Unlike Rebecca, who decided to pursue law early on (she cowrote a

paper on joint and several liability with her father in high school),

Scot earned a degree in chemistry and was considering his career options

when his advisor suggested patent law as a way to combine two

interests.

Scot recalls that family vacations were planned around the court

schedules of his father and grandfather. His grandfather's succession of

boats the family used at their Canadian island getaway were all

appropriately named "Trial's End."

Is there a sixth generation of attorneys in the wings for the

Wickhems? Of his own children, Scot says wryly, "I'll try to steer them

into medicine, but who knows whether I'll succeed?"

Sharing a Dream: The Pittses

Christina (seated) and Trinette Pitts share more than a name and

close relationship.

This mother/daughter duo realized a shared dream of becoming lawyers,

attending U.W. Law School and even rooming together for two years.

Trinette (U.W. 1982) opened the family's Milwaukee practice in 1984;

Christina (U.W. 1983) joined her full time in 1986.

For Christina Pitts and her daughter, Trinette, becoming a lawyer was

a shared dream realized together.

Christina wanted to pursue a law career when she graduated from high

school at age 16, but her sister was already in college, and her family

could afford tuition for only one at a time. So she went to Milwaukee to

wait her turn and work in her sister's business. She met and married

Clifford Pitts instead.

Trinette traces her own interest in the law to hours she spent after

school watching her mother at work in the Milwaukee County circuit court

as a deputy clerk. "What I didn't know was that she had always aspired

to be a lawyer, too," Trinette says.

They received their undergraduate degrees on the same day in the

spring of 1979, Trinette in a morning ceremony at Marquette University,

and Christina that afternoon from U.W.-Milwaukee. Trinette headed for

U.W. Law School that fall, and her mother followed a year later. For two

years they roomed together and shared the limelight. Christina

acknowledges that Trinette was more comfortable with the attention

surrounding their unique status than she was.

"I remember once being up studying at 3 a.m., wondering, 'What am I

doing? I left a good job for this?'" Christina recalls. "But then I

realized there was no quitting even if I wanted to. I thought, 'If I

flunk out of here, everyone will know.'"

They share a close relationship - Trinette's only concern about their

shared practice is that their offices at opposite ends of the suite are

too far apart - and complementary personalities. Christina remembers an

advisor telling them as they prepared for their moot court competition

in law school, "You'll make a great team. Trinette goes for the jugular,

and you come behind and soothe the ruffled feathers."

Trinette spent a couple years working for another Milwaukee law firm

before she opened the family practice in 1984. Christina, who had

returned to Milwaukee County first as an assistant corporate counsel

processing paternity cases and later as an assistant district attorney,

worked after hours with her daughter and joined Pitts & Pitts, which

bills itself as "the women who care about you," full time in 1986.

Their practice is truly a family business, with son/brother Robert

working as the office manager. Even husband/father Clifford Pitts Sr.,

now a full-time pastor, has caught the law bug, sprinkling his sermons

with legal terms.

"He'll come to us and say, 'Tell me about codicils,'" Trinette says.

"Many people in his congregation know we're lawyers, and they just love

it."

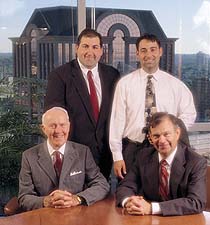

Talking Law: The Tierneys

"A lot of people view having the same name and pursuing the same

career as a burden," says Joe Tierney IV (back row, right), "but I've

never felt that way." Having a familiar and respected name helps in

getting to know people, and with four close relatives practicing law

nearby, one never lacks advisors. Gathered in Milwaukee, the Tierneys

are (from left) Joe Jr., Martin, Joe IV, and Joe III.

As Martin Tierney launches his legal career this summer, joining

Ernst & Young in Chicago to practice in tax and employee benefits

law, he'll have a ready pick of advisors to kick around a quick

question. Martin's grandfather, father, and brother, all named Joe,

practice corporate, tax, and real estate law in Milwaukee.

The first Joe Tierney to practice law came from Menominee, Mich., to

study at Marquette University. He graduated in 1913 and went on to

become the first assistant DA in the Milwaukee County District

Attorney's Office. "He also trained a lot of lawyers," says his son

Joseph Tierney Jr., a partner with Cook & Franke, who met many

colleagues over the years who spoke fondly of his father's tutelage.

Joe Jr. joined the FBI straight out of law school in 1941 and worked

with an espionage group in New York during World War II. After the war

he worked in the Waukegan FBI office before he returned to civilian life

as a CPA with Arthur Anderson. By the time he returned to Milwaukee to

practice law, his son, Joseph III, had already launched his own

practice.

Joe III, a partner with Meissner Tierney Fischer & Nichols,

recalls no expectations that he take up the law, but adds, "I can't

imagine doing anything else that would be as interesting. I created my

own expectations, and I tried to do the same for my own sons."

Martin notes that "a lot of my friends in grade school and high

school expected me to become a lawyer, but I never felt any pressure

from the family. In fact, my parents did a wonderful job of getting

behind me when I considered studying quantum mechanics."

Martin's brother, Joe IV, has been redirecting phone calls and email

messages intended for his father and grandfather since he began

practicing in Milwaukee. "It's always a treat picking up the phone and

hearing, 'Joe, I haven't talked to you in 20 years,'" he says. "That

would have made me about six."

But Joe IV, an associate with Domnitz, Mawicke, Goisman &

Rosenberg, wouldn't trade places with a Tom or Sam.

"A lot of people view having the same name and pursuing the same

career as a burden, but I've never felt that way," he contends. "Because

people know my father and grandfather and like them, that opens doors

for me. I don't mean economically, but just in getting to know people. I

feel like I have a sense of history."

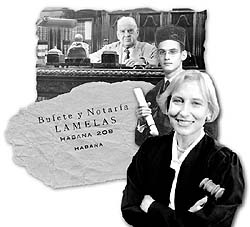

Seeking Justice: The Lamelas Family

The events witnessed as a child in Cuba and the years the Lamelas

family lived in poverty after first arriving in the United States

influenced the career choices of Elsa de la Caridad Lamelas Salazar, now

known as the Hon. Elsa C. Lamelas of the Milwaukee County circuit court

(below right).

In a picture taken in the family's Havana law firm in the 1950s,

Francisco José Lamelas Collado is seated at a mahogany table carved

by a European craftsman who fled to Cuba during WWII.

"How ironic that a few years later he, too, would have to flee and

leave all behind," says Elsa of her grandfather. "Everything was seized

by the Castro government." A scrap of an old manila envelope with the

law firm name and address is all that remains of the family's firm.

Upon his graduation from the Universidad de la Habana in 1941,

Francisco José Lamelas Blanco (Elsa's father, shown in his

graduation picture) became the youngest member of the Havana Law

Association when he joined his sister and father in the family law

practice.

When Francisco José Lamelas joined his sister and father in the

family law practice in Cuba, he became the youngest member of the Havana

Law Association. He practiced law in his homeland for 20 years, actively

seeking legal reforms, and was busy with a full trial schedule. Then

Fidel Castro came to power, and "things started getting bad little by

little," he recalls. "Being a lawyer became very controversial."

It was time to get the family out of Cuba. Daughters Elsa and Blanche

left first in what were called "Peter Pan" airlifts transporting

children to U.S. orphanages. Next came his wife and young son.

"I was the last one, and I wasn't sure I would be allowed to leave,"

Francisco says. The day before he left, a justice at a Supreme Court

hearing attempted to provoke him into a confrontation that might have

landed him in prison. "I handled that very well, but nobody could be

safe from the government."

After they were reunited, the Lamelases settled in Chicago where

Francisco started law classes, but he discovered he could not finish law

school in the requisite five years while working full time to support

his family. Instead, he found a job as a law clerk and later taught

Spanish language and literature at Dominican College in Racine. His

final career move was to become a juvenile probation officer for 18

years with Milwaukee County.

"I am a lawyer by nature," Francisco acknowledges. He enjoyed

interacting with his juvenile clients and the legal system. And he is

proud that a third generation of the Lamelas family has taken up

law.

Elsa Lamelas crisscrossed the country as an attorney for the Civil

Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice before settling down

in Milwaukee, where she worked with the Equal Employment Opportunities

Commission, the district attorney's office, and finally the U.S.

attorney's office before her appointment to the Milwaukee County circuit

court bench.

As Elsa discusses her career choices, she recalls "the dramatic

events I witnessed in Cuba that I will never forget" and the years her

family lived in poverty after first arriving in the United States. "I

really thought the law was an instrument to change the world, and I very

much wanted to do that," she says simply.

Hometown and Beyond: The O'Melias

Gathered for a family portrait are O'Melia attorneys (from left) John

Jr., Richard, Michael, and Patrick. Brothers John Jr. and Patrick

practice in the family's Rhinelander firm, their uncle Richard practices

in Washington, D.C., while cousin Michael is a circuit judge in Phoenix,

Ariz.

In Rhinelander in the first half of the century, no one was surprised

when the doctor's child became a doctor or the dentist's son took up

dentistry, recalls Richard O'Melia. The fact that three of Albert J.

(A.J.) O'Melia's sons took up the law was a bit more remarkable.

A.J. O'Melia opened his practice in 1911 after graduating with the

first class out of Marquette University Law School. Two sons, Donald and

John, joined him in the Rhinelander office, while Richard opened the

Milwaukee office of O'Melia and Kaye after completing law school

following service as a Marine fighter pilot in World War II.

Richard went to Washington with family friend Joe McCarthy after

helping with McCarthy's 1952 Senate campaign. "I said I'd go for one

year, and it's been 50," says Richard, who served as general counsel

with the U.S. Senate Operations Committee, which McCarthy chaired. He

later worked on staff with the Civil Aeronautics Board before being

appointed to CAB in 1974. More recently, he became one of the founders

of U.S. African Airways.

Back home, the third generation of O'Melias entered the profession.

In 1979 John Jr. joined his father and uncle in the family firm, now

O'Melia, Schiek and McEldowney. His brother, Patrick, also joined the

practice for several years before becoming Oneida County District

Attorney in 1989.

Their uncle Donald's son, Michael, is a circuit judge in Phoenix, and

his daughter, Amy O'Melia-Endres, recently became a fourth generation

O'Melia lawyer after graduating from Arizona State University Law

School. John Jr. didn't decide to become a lawyer until his second year

in college, though he recalls attending his father's trials while in

high school and once was invited behind the scenes to watch as jury

instructions were drawn up in chambers. Once he decided on the law, "I

always assumed I would come back to Rhinelander and practice with my

father and uncle."

Conclusion

As diverse as these lawyerly families may be, they share an abiding

passion for their work. "This is a wonderful profession that encourages

pro bono work," says Joe Tierney Jr. "It gives us the opportunity to

help people who need help, and we enjoy doing it."

That frame of reference is itself a strong legacy. Notes grandson

Martin, "Because of my father and grandfather, I had a great deal of

respect for the law and still do."

Tedia's mother, Sherry Ackerman, is a Spanish teacher, and Tedia

thinks it fitting that the public defender's office hired her as much

for her knowledge of Spanish as for her law degree. "I get to use my

mother's skill in my father's profession," she says.

Karen Bankston is a first

generation writer/editor based in Stoughton.

Wisconsin

Lawyer