Headwaters of Three Springs near Sister Bay. Photo by Joanne Kline.

Wetlands are critical ecosystems that help reduce flood severity, filter polluted runoff before it reaches open water, and provide waterfowl and wildlife with food and shelter.

In 2020, rollbacks in federal protection of waterways and wetlands under the Clean Water Act left millions of wetland acres in Wisconsin vulnerable to development. Although Wisconsin law protects many waterways and wetlands that are no longer covered by federal regulation, continued weakening of state protections could lead to wetland loss around the state.

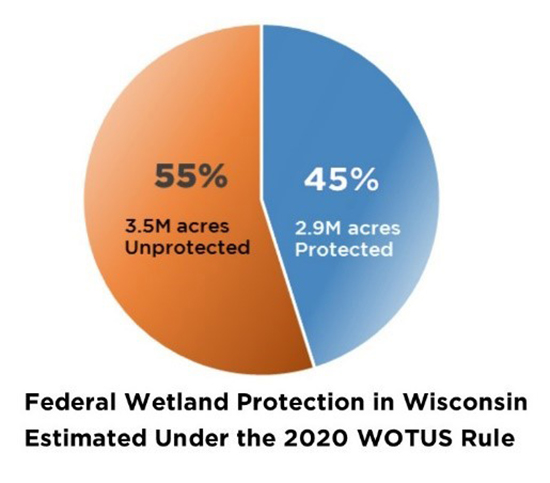

Wisconsin’s Green Fire: Voices for Conservation (WGF) and The Nature Conservancy in Wisconsin collaborated on developing an assessment tool to determine the impacts in Wisconsin of the federal rollbacks. We determined that 55% or more of Wisconsin’s remaining wetlands lost federal protection.1

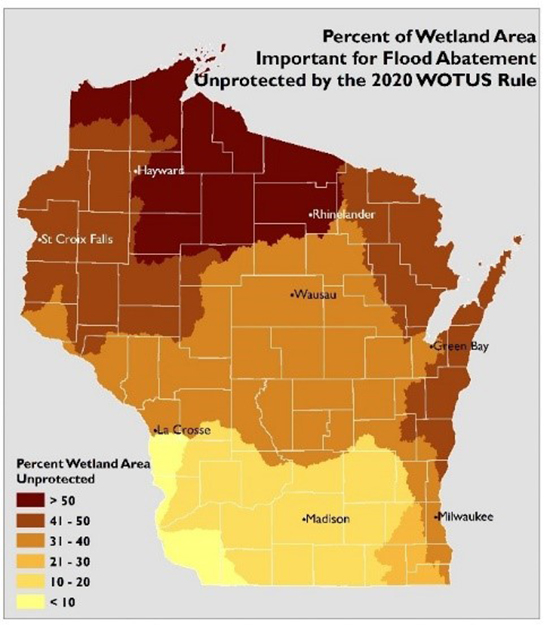

As an example of the impacts, in northern Wisconsin, a high percentage of wetlands that offer flood protection are no longer protected under the Clean Water Act.

Federal Definitions of the ‘Waters of the U.S.’ under Clean Water Act

With passage of the Clean Water Act (CWA) of 1972,2 agencies of the federal government began working in earnest to curtail water pollution. The CWA is landmark legislation that reversed decades of degradation of the nation’s waterways, but the question of exactly which waters are covered by the CWA has generated highly conflicting opinions since the law was initially passed.

Michael Cain, U.W. 1975, retired after 34 years as staff counsel at Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, where he practiced in surface water and wetland issues. He currently serves on the board of Wisconsin’s Green Fire and is co-chair of their Public Trust/Wetland Work Group.

Michael Cain, U.W. 1975, retired after 34 years as staff counsel at Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, where he practiced in surface water and wetland issues. He currently serves on the board of Wisconsin’s Green Fire and is co-chair of their Public Trust/Wetland Work Group.

Activities that impact shorelines or wetlands, aquatic habitat, or water quality such as dredging, earthwork or the placement of fill material, and non-point source pollution are regulated under different sections of the CWA. For some sections of the CWA, authority is delegated to states and Tribes to manage regulatory programs enabled by state statute and tribal authority.

Over the years, the definition of Waters of the U.S. (WOTUS) has been highly contentious. The WOTUS definitions provide the foundation for the scope and jurisdiction of the federal CWA programs, so these definitions are critical for both federal and related state water protection programs.

There has been extensive litigation resulting in a myriad court decisions, including key decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court. This history is beyond the scope of this blog, but I will discuss a couple of key judicial decisions below. I also briefly discuss the analysis that WGF has completed with The Nature Conservancy relative to the impacts of the 2020 iteration of the WOTUS rule.

History of Wisconsin’s Water Protections

Wisconsin has long been a leader in protecting its valuable water resources. The Wisconsin Constitution incorporated provisions of the 1787 Northwest Ordinance declaring that:

the river Mississippi and the navigable waters leading into the Mississippi and the St. Lawrence, and the carrying places between the same, shall be common highways and forever free. …3

This language serves as the cornerstone of Wisconsin’s public trust doctrine, which protect its navigable waters and many of its wetlands.

In 1914, in recognizing the public nature of these waters and recognizing the public’s right to travel, fish, hunt, and recreate on these waters, the Wisconsin Supreme Court noted that we need to broadly construe the public trust doctrine so the “people reap the full benefit of the grant secured to them” relating to our waterways. The Court further noted that the:

wisdom of the policy which steadfastly and carefully preserved to the people the full and free use of public waters cannot be questioned. Nor should it be limited by narrow construction.4

One of Wisconsin’s adopted sons, Aldo Leopold, served to reinforce the foundations of Wisconsin’s long heritage of protecting its water resources when he articulated the “land ethic,” where people move “from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it.”5 This conservation ethic and the ecological principles articulated by Leopold and others as the science of ecology evolved to serve as the modern foundation of many state and federal environmental programs.

In a case involving fill placed in a navigable lake in Wisconsin in 1966, the Wisconsin Supreme Court upheld the denial of a permit, stating:

one fill, though comparatively inconsequential, may lead to another and another, and before long a great body of water may be eaten away until it may no longer exist. Our navigable waters are a precious natural heritage; once gone, they disappear forever.6

With 50 years’ experience in developing and enforcing regulations relating to Wisconsin’s wetlands, I can attest that this principle applies with equal vigor to all Wisconsin wetlands.

In 1972, the Wisconsin Supreme Court issued a decision denying a project that proposed filling wetlands adjacent to a lake and upheld Wisconsin’s shoreland zoning regulation. The Court said:

Swamps and wetlands were once considered wasteland, undesirable, and not picturesque. But as the people became more sophisticated, an appreciation was acquired that swamps and wetlands serve a vital role in nature, are part of the balance of nature and are essential to the purity of water in our lakes and streams.7

This language demonstrated an evolving recognition in 1972 of the science of ecology and of the land/water ethic articulated by Leopold and others. The Court further noted, consistent with this ethic, that it is not reasonable for a property owner to assume that they can destroy the “essential natural character” of the land, in this case, wetlands, “so as to use it for a purpose for which it was unsuited in its natural state.”

These cases, Wisconsin’s public trust doctrine, and the science and hydrology that recognize the connections of all Wisconsin waters, underpin Wisconsin’s laws on wetland protections.

Wisconsin’s Wetland Regulatory Program

Wisconsin has been a national leader in development of its wetland regulatory programs. In 1978, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources adopted a wetland protection policy that provides, in part:

The natural resources board is concerned with the continuing reduction in the quantity and quality of natural wetlands in this state and is committed to reversing the loss of our state's wetlands. A large percentage of Wisconsin's wetlands have been altered or destroyed in the years since settlement. It is the policy of the natural resources board that wetlands shall be preserved, protected, restored and managed to maintain, enhance or restore their values.8

In 1978, the Wisconsin Legislature also mandated the establishment of the Wisconsin wetlands inventory to map Wisconsin’s remaining wetland resources. The map resources and database established under these mapping activities have, in part, served as the basis for the WGF/Nature Conservancy analysis of the impacts of the 2020 WOTUS rule.

In 1981, Wisconsin developed rules for processing water quality certifications under Section 401 of the CWA.9 In 1991, Wisconsin adopted water quality standards for wetlands after extensive public hearings and public input.10 These wetland water quality standards apply to all Department of Natural Resources “regulatory, planning, resources management” determinations that affect wetlands.

In 2001, a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in the Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County (SWANCC) removed federal authority over “isolated wetlands.”11 This had the effect of removing federal jurisdiction over approximately 1 million acres of wetlands in Wisconsin, and there were significant concerns about the potential impacts of the loss of such wetlands on water quality and habitat.

The Wisconsin Legislature adopted, unanimously in both houses, legislation that declared that any wetland declared nonfederal under SWANCC or any subsequent interpretations of that decision by federal courts or agencies, would be subject to Wisconsin regulation.12

Rapanos and the Connectivity Report

In 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court again grappled with the extent of federal jurisdiction under the CWA. In the Rapanos case, there were multiple opinions expressed by the Court justices, who split 4-1-4 on the scope of the CWA.13

Four conservative justices opined that the WOTUS should be defined narrowly, four liberal justices called for a broad interpretation, and Justice Kennedy filed a separate opinion asserting that waters that had a “significant nexus” to navigable waters of the U.S. should be covered under the CWA.

The federal government undertook an extensive analysis of the scientific and hydrologic information that supported such “significant nexus,” and prepared the extensive, 400-page Connectivity Report to demonstrate the appropriate scope of the WOTUS definition. The report was described by Environmental Protection Agency as:

review(ing) more than 1,200 peer-reviewed publications and summarizes current scientific understanding about the connectivity and mechanisms by which streams and wetlands, singly or in aggregate, affect the physical, chemical, and biological integrity of downstream waters.

The EPA published a WOTUS rule in 2015 based on the science and hydrology in the Connectivity Report. It was the subject of extensive litigation, and was enjoined by federal courts in 28 states.

In 2020, the Trump Administration undertook a new rulemaking process, and adopted a new WOTUS rule, the Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR), which resulted in the removal of coverage of many streams and wetlands.

EPA’s own Science Advisory Board (SAB) objected to the 2020 rule, noting, among other objections:

The proposed Rule does not present a scientific basis for adopting a surface water-based definition of Waters of the U.S. The proposed definition is inconsistent with the body of science previously reviewed by the SAB, while no new science has been presented. Thus, the approach neither rests upon science, nor provides long term clarity.

We conferred with Wisconsin and federal agencies to discern the impacts of the 2020 WOTUS rule, but did not receive definitive answers since there was a dearth of guidance within the federal agencies concerning how the 2020 rule would be administered.

Wisconsin’s Green Fire and Wisconsin Nature Conservancy Analysis

The work that WGF and The Nature Conservancy has undertaken is an effort to identify in Wisconsin which wetlands and waters are not covered under this iteration of the WOTUS rule. Our analysis was specific to wetlands and did not examine the changes in federal protection of ephemeral and intermittent streams, which are important to healthy watersheds.

Whether a wetland meets the 2020 WOTUS definition depends on its position in the landscape, how water flows in the wetland, and whether the wetland is adjacent to and interacts with waterbodies. These same factors determine the types of ecological services wetlands can provide to society, such as flood abatement.

In a joint project of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and The Nature Conservancy, Wetlands by Design, to assess wetland services, these factors were assessed for wetlands statewide by combining information from the Wisconsin Wetland Inventory with data from a GIS analysis. Because the factors for determining wetland benefits are similar to factors for determining federal jurisdiction, WGF and The Nature Conservancy used the results of this project to evaluate the impacts of the 2020 WOTUS rules on Wisconsin’s wetlands, in terms of both acres and wetland services at risk.

We determined that the 2020 WOTUS rule removed federal protections from approximately 55% (3.5 million acres) of wetlands in Wisconsin, including isolated wetlands, floodplain wetlands that are not inundated in a “typical year” by their associated stream or river, and wetlands that discharge groundwater to other waterbodies. See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Federal wetland protection in Wisconsin estimated under the 2020 WOTUS rule leaves 55% unprotected. Used with permission.

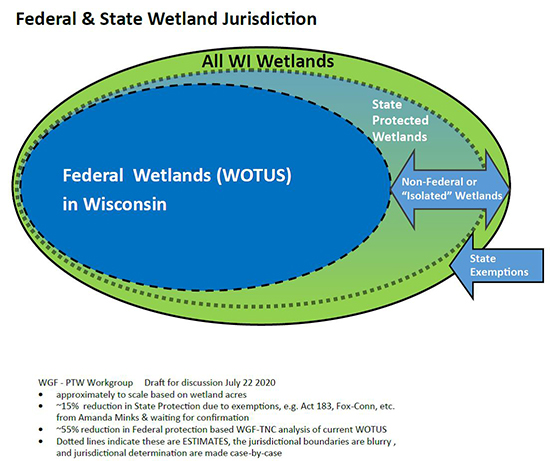

As discussed above, Wisconsin adopted a statute in 2001 that assured that wetlands declared nonfederal would be protected under Wisconsin law and Wisconsin’s wetland water quality standards. This statute has captured those wetlands found to be nonfederal under the recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions and the 2020 WOTUS rule.

2018 Act 183 granted some permitting exemptions to activities that adversely impact certain types of artificial wetlands and nonfederal wetlands. This reduced protections for a subset of the nonfederal wetlands. See Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Federal and state wetland jurisdiction. Used with permission.

At this point in time, there has been no analysis of the scope and impact of activities to these wetlands that were exempted under 2018 Act 183. One of WGF’s recommendations is to undertake such an analysis to determine the impacts those exemptions have had on Wisconsin wetland resources and to further assess the potential impacts of the 2020 WOTUS rules.

The broad wetland analysis by WGF and The Nature Conservancy is designed to look at the various ecological services that wetlands provide, such as flood abatement, water quality protection, carbon storage, and shoreline protection.

Flood Water Storage and the WOTUS Rule

While the scope of this analysis cannot be described in this blog post, here is an example of an ecological service with direct interest and potential benefits to many people: flood water storage.

Statewide, our assessment estimates that 2.5 million acres of wetlands that contribute to managing floodwaters would not be protected by the CWA under the 2020 WOTUS rule. Fig. 3 demonstrates results for different areas in Wisconsin.

Fig. 3. Wetland areas important for flood abatement that are unprotected by the 2020 WOTUS Rule. Used with permission.

As recent blogs of the State Bar of Wisconsin Environmental Law Section have discussed, flooding and water level changes due to increased frequency and amounts of precipitation are significant issues in Wisconsin. Andrea Gelatt, in her Dec. 14, 2020, blog article Developing Flood Resilience in Wisconsin, referenced the occurrences where “western Wisconsin was hit by deadly 2018 storm events. And, tragic floods – technically classified as ‘500-year floods’ – struck our northern counties in 2012, 2016, and 2018.”

Richard Manthe, in his Feb. 4, 2021, blog article Resurgence of the Reasonable Use Rule, noted that “flooding continues to present a significant challenge across Wisconsin. Directing and controlling the drainage of surface water is a challenge that developers, farmers, and other property owners must grapple with.”

In addition to ecological and legal issues raised by these changes, increased flooding also raises environmental justice issues. As an example, flooding disproportionately impacts low income communities of color in Milwaukee. Like many other cities across the U.S., Milwaukee witnessed historic development practices that pushed low income and communities of color into low lying flood prone areas most at risk of natural disasters.14

In northern Wisconsin, First Nation and other communities have also encountered severe storms that have generated widespread flooding and damage. In 2016, the Bad River watershed received 8 to 10 inches of rain in an eight-hour period, severely flooding the Bad River and its tributaries. The storms washed out roads and damaged millions of dollars’ worth of critical infrastructure on the Bad River Reservation, home of the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians.15

We invite you to look at the full report by WGF and The Nature Conservancy, which describes in some detail the types of wetlands that are at risk in Wisconsin under the 2020 WOTUS rule. In addition, WGF and The Nature Conservancy are now looking beyond flooding issues to consider the potential impacts of the 2020 WOTUS rule on a broader range of wetland services, including water quality, habitat, and streamflow maintenance.

Conclusion: Gaining Tools for the Future

The debate over the scope of the WOTUS definition in the CWA will continue for the foreseeable future. One commentator recently referred to as part of our “culture wars.”16 The stakes are significant for Wisconsin, with its extensive water resources.

WGF will be publishing a set of executive and policy recommendations for dealing with these issues going forward. These will include a recommendation to repeal and replace the 2020 WOTUS rule to provide a rule that is based on science.

We also recommend that federal legislation be introduced to clarify the scope of the CWA to avoid the continued confusion and uncertainty for all stakeholders. While some will decry this as naïve, there is precedent for this approach. Wisconsin’s wetland program, which captures all wetlands in a regulatory program that has worked effectively for all stakeholders, demonstrates that such an approach is workable.

The analytical models that WGF and The Nature Conservancy are developing will be useful tools in assessing potential future impacts on the waters, the resources and the citizens of Wisconsin. The work is not completed, and the technical experts who have developed these tools are working to have their work peer-reviewed and, hopefully, applied on a larger scale than just Wisconsin.

It is our hope that these tools can be utilized by state and local decision makers as they assess the potential impacts of activities throughout Wisconsin that impacts our wetlands and waterways.

If you continue to have interest in these issues, check the Wisconsin’s Green Fire website, where a more comprehensive analysis and a full slate of our policy recommendations has been posted.17

This article was originally published on the State Bar of Wisconsin’s Environmental Law Section Blog. Visit the State Bar sections or the Environmental Law Section webpages to learn more about the benefits of section membership.

Endnotes

1 For the full report on the WOTUS/NWPR analysis, see the report on the Wisconsin Green Fire website. The analysis referenced in this blog post was prepared by technical experts of Wisconsin’s Green Fire and The Nature Conservancy in Wisconsin. We will be issuing a more comprehensive analysis, including recommendations for Executive and Policy Actions in an “Opportunities Now” analysis on the Green Fire website.

2 33 U.S.C. §§ 1251–1387.

3 Wis. Const. art. IX, § 1.

4 Diana Shooting Club v. Husting, 156 Wis. 261(1914).

5 Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac; and Sketches Here and There, 203-04 (Oxford University Press, 1949).

6 Hixon v. PSC, 32 Wis 2d 608 (1966).

7 Just v. Marinette County, 56 Wis. 2d (1972).

8 Wis. Admin. Code ch. NR 1.95(1978).

9 Wis. Admin Code ch. NR 299.

10 Wis. Admin Code ch. NR 103.

11 SWANCC v. Corps of Engineers, 531 US 159 (2001).

12 See Wis. Stat. § 281.36 (2007).

13 Rapanos v. U.S., 547 US 715(2006).

14 U.S. Water Alliance, 2020. Water Rising: Equitable Approaches to Urban Flooding.

15 United States Geological Survey, 2017. Measuring the July 2016 Flood in Northern Wisconsin and the Bad River Reservation.

16 See Biden Swings Waters Pendulum With Final Resolution Still Elusive, Bloomberg Law, Jan. 29, 2021.

17 WGF membership is open to both professionals and non-professionals committed to maintaining Wisconsin's conservation tradition. To learn more or to join, visit the WGF website.