Lawyers at Play

By Kurt Chandler

|

To ease the pressure-cooker demands of legal

practice, Wisconsin lawyers have found a curious assortment of things to

do after the workday ends.

|

As one Wisconsin attorney explains, the essential work of any lawyer

involves solving somebody else's problems. Even on the most gratifying

cases, that responsibility can make for some awfully stressful days, as

most lawyers will attest.

To ease the pressure-cooker demands, Wisconsin lawyers have found a

curious assortment of things to do after the workday ends. Sometimes the

off-hour pastime is a budding second career, sometimes it's a

long-standing hobby, and sometimes it's just plain fun. Here, your peers

define the frequently foreign concept of "Lawyers at Play."

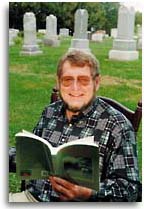

Dennis Boyer, ghost story writer

He's got a story about a ghost that inhabits a cheese factory in New

Glarus, one about spirits in an abandoned brewery in Potosi and another

about a phantom herd of grazing cows, which appears now and then in a

Richland County pasture.

Dennis Boyer admits to having seen something out of

place one night among the gravestones of a cemetery near his farm in

Dodgeville. A collector of ghostly anecdotes of rural Wisconsin, Boyer

published some of his stories in Driftless Spirits.

|

Dennis Boyer writes ghost stories, not the Stephen King variety, but

stories that he's collected as he's traveled the byways of Wisconsin. A

lawyer since 1980 with the state office of the American Federation of

State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), Boyer's traveling job

has taken him into coffee shops and taverns in nearly every county in

the state.

And he's heard the strangest things from the people he's met -

stories about a phantom fisherman along Iowa County's Mill Creek and a

half-pig, half-human creature in Adams County.

"I've been storing up these anecdotes for eight or 10 years," he

says.

A few years ago, Boyer, a graduate of the West Virginia University

Law School, took some time off to care for the firstborn of two sons

while his wife, Donna Weikert, also a lawyer, worked for a teacher's

union. As his son napped at home in their farmhouse near Dodgeville,

Boyer began pulling together some of the anecdotes. The stories grew

into two self-published books, Ghosts of Iowa County and

Iowa County Folk Tales.

In his latest book, Driftless Spirits, published last year

by Prairie Oak Press in Madison, Boyer relates 46 tales of the

paranormal, using ghost stories as a device to examine folklore in

southwestern Wisconsin.

Unlike urban horror stories in which ghosts are typically seen as

threatening, rural phantoms are regarded almost like patron saints or

guardian angels by local residents, says the 47-year-old author.

"In hearing these stories, I started to wonder if people were

commenting on a passing way of life," he says.

Driftless Spirits includes stories about apparitions,

including the tale of a World War Two-era trapper whose incorporeal form

old-timers periodically see roaming the countryside - and Boyer's own

farm.

Boyer, who says he "concedes to the possibilities" of the

supernatural, admits to having seen something "out of place" one night

among the gravestones of a cemetery near his home.

Boyer's childhood prepared him well for his storytelling. Born to a

Pennsylvania Dutch family, his relatives were conscientious in handing

down family oral histories dating back to the Revolutionary War.

Due out this fall from Prairie Oak Press is Boyer's Giants in the

Land, a collection of Wisconsin tall tales in the tradition of Paul

Bunyon or the Rhinelander Hodag.

"There's nothing in here that's even remotely plausible," he says.

"These are fun stories told by people after they've had maybe too many

Tom Collinses."

Boyer's work as a writer provides a creative outlet that his legal

career does not.

"In my job [as AFSCME's government relations counsel], I tend to deal

with fairly weighty stuff all the time." It's refreshing, he says, to

sit down with folks, crack open a beer or two, and listen to them spin

tall tales.

"I'm having far more fun than I ever imagined."

Rick Smith and Michael Reyes, jazzmen

Ask Rick Smith what he was doing before he went to law school and he

pleads guilty to enjoying the freewheeling life of a hippie.

"I was living kind of free and easy," confesses Smith, 46. He

traveled around the United States and lived in South America for a

while, teaching English in Colombia.

In 1996 jazz aficionados Rick Smith and Michael Reyes

coproduced a concert featuring the Gato Barbieri Quintet. (Above from

left: Smith, bass player; Mario Rodriquez, saxophonist; Gato Barbieri,

Reyes and Rosemary Cuevas-Reyes.

Photo by Pat Robinson.

|

"Law school was the turning point for me, in that it caused me to

become serious and focus on the idea of a career."

Although he's practiced law since receiving his J.D. from the

University of Wisconsin Law School in 1981, Smith has remained true to a

few of his hippie-day roots, particularly his love for music.

"Like a lot of kids in the '60s," he says, "I played a little guitar,

and I always liked the saxophone."

Michael Reyes, meanwhile, has been a more studied musician. Raised in

the Cleveland area, with family roots in Puerto Rico, Reyes studied

music in college and played guitar for most of his life.

"I was always influenced by a lot of different musical styles," says

Reyes, 36, "music from the Caribbean, rock 'n roll, rhythm and blues,

flamenco, Latin jazz."

While also attending law school at U.W.-Madison, Reyes began

producing concerts. When he moved to Milwaukee eight years ago, he

started organizing musical workshops within the Hispanic community.

The devotion to music held by Smith and Reyes led them by chance to

become jazz impresarios in Milwaukee.

Both had been invited to sit on an advisory committee to the Artist

Series at the Pabst Theater. And through that committee, both were

invited to join the board of directors for the Friends of WYMS, an FM

radio station that broadcasts jazz six days a week.

To raise funds for the station, Smith and Reyes produced a CD of some

of Milwaukee's most notable jazz players, musicians such as trumpet

player Brian Lynch, pianist David Hazeltine and saxophonist Frank

Morgan, a protegé of Charlie Parker. The WYMS Jazz Sampler went on

sale in October 1996. (Copies can be purchased by contacting the station

at (414) 475-8890. All proceeds go to the station.)

Recruiting the players, booking studio time, coordinating the

recording sessions and designing the CD took a full year. "It was a

marathon project," says Smith.

In 1996 Smith and Reyes coproduced a concert featuring the Gato

Barbieri Quintet. Out of that grew Yemay Productions, a concert

promotion company (named for the African goddess of water and rhythm),

run by Smith, Reyes and attorney Scott Wales.

"Jazz is vital," Smith declares. "I'm real interested in young

players who are playing vital, new jazz."

Reyes, through Yemay and other ventures, has been successful in

bringing a diverse blend of musical acts to the area, including a

concert titled the Thunder Drums Tour - two percussion virtuosos from

Cuba who performed early this year only in New York, San Francisco,

Chicago and Milwaukee.

"I find music to be almost therapeutic," says Reyes, who lives in

Glendale with his wife, Rosemary, also a lawyer. "I find inspiration

through music, from the various genres. I've fortunately been able to

work my schedule around so I can get involved with other

activities."

"There are some lawyers who just work all the time, they're consumed

by their work," says Smith, who lives with his wife, Valerie Ko-Smith,

and their two daughters in Wauwatosa. "Of course, if you ask my wife,

she would probably say I am consumed by my interest in jazz."

Indeed he is. When he's not promoting concerts or producing CDs,

Smith is learning to play the alto sax.

Mary Triggiano-Hunt, snowmobile racer

As if the life of an attorney isn't fast-paced enough, Mary

Triggiano-Hunt finds it necessary to race snowmobiles - often in excess

of 100 miles per hour.

Mary Triggiano-Hunt, Milwaukee, credits husband, Ken,

for her thrill-seeking pastime of racing snowmobiles against the clock.

The wife-husband team has won or placed in 69 races in the last four

years.

|

By weekday, she's the managing attorney of Legal Action of

Wisconsin's Milwaukee office, providing free legal service to low-income

clients.

But by weekend, when the snow flies, she and her husband are off to

the plains of northern Minnesota, setting speed records across the

surfaces of frozen lakes.Triggiano-Hunt credits (or perhaps blames) her

husband for her thrill-seeking off-hour pastime. In the late 1970s,

before the two met, Ken Hunt designed and raced snowmobiles for Polaris

in Roseau, Minn. After relocating to Wisconsin, he went to work for John

Deere in Horicon and continued to race. Triggiano-Hunt became a member

of his pit crew.

Eventually, he coaxed her into joining him on the circuit. "Three

years ago he put me on a sled and I started racing," she says. "It

became part of our lives."

She began doing "speed runs," racing down a quarter-mile drag strip.

And before long, the two of them were on the Polaris A-team, setting

records.

"We started kickin' butt," says the 34-year-old Triggiano-Hunt, who

lives in Oconomowoc. In 1995 she set a world record. "I went about 114

mph in a quarter mile. That's about 8 seconds down the track."

"It's exhilarating, but it ends real quick because it's such a short

track. So you want to do it again."

In the last four years, the husband-wife team has won 45 first-place

and 24 second-place finishes, including six world records through the

National Snowmobile Speed Run Association. In 1995 Triggiano-Hunt was

named NSSR Rookie of the Year.

Born and raised in Racine, Triggiano-Hunt graduated from law school

at the U.W.-Madison in 1988. She went to work in 1994 at Legal Action, a

federally funded agency that assists low-income clients in civil cases,

mostly involving public benefits, housing issues and family law.

"I really saw that there was a need out there for people without

money who needed our assistance. Attorneys sometimes have the key to the

solutions to people's problems. The underprivileged often don't have

means, wherewithal or resources."

Gliding across an icy lake on a snowmobile releases her from the

stress of a job she truly enjoys.

"Even going 114 mph, though, is not as exhilarating as being able to

help clients and knowing that you've done something for those clients

that may help them turn their lives around."

And what does she do for thrills in the summer, after the snow has

long melted away? "I ride a Harley," she says.

Of course.

Amy Sanborn, equestrienne

The sport of dressage is performed, not played. A uniformed rider

mounts a horse inside a 20x60-meter arena bordered by a short, white,

wooden fence. The rider salutes the judge, and for eight long minutes,

leads the horse through a series of as many as 30 choreographed

maneuvers, commanding the animal through slight movements of her hands

and legs.

Amy Sanborn, Madison, trains to perform at the Olympic

level in the sport of dressage. When dressage is done right, horse and

uniformed rider become one. Sanborn's been doing it right for nearly 20

years.

|

When it's done right, dressage is detailed, precise, elegant - a

four-legged equivalent to figure skating or gymnastics. When it's done

right, horse and rider become one.

Amy Sanborn has been doing it right for nearly 20 years; so right, in

fact, that she has won several state championships and now competes at

the national and international rank. Ten years ago, she was chosen to

spend a summer of training at France's national equitation school.

"I've been around horses since I was two," says Sanborn, whose mother

raises horses on a 120-acre farm near Verona, southwest of Madison. "I'm

not overly confident in the law, but riding and training horses is one

area I feel extremely confident in."

A graduate of Cornell Law School in Ithaca, N.Y., Sanborn, 33,

divides her time between the farm and her law office in Madison. But her

legal practice is transitory. Two years ago, she formed Silent Partner

Legal Services, a freelancing, lawyer's "temp service." She markets

herself to small firms as a practitioner-for-hire, employed on a

temporary basis to practice general law when a firm is short-handed or

has a scheduling conflict, for example.

Practicing law, riding horses and caring for her two sons - ages 10

months and two-and-a-half years - thoroughly fills her days. Yet Sanborn

also finds time to teach high-impact aerobics and kick-boxing at a

Madison health club.

"That's just for fun," she laughs, "and it complements the riding.

You need to be strong, you need muscle control to communicate with the

horse in a subtle way."

Dressage is her true passion. To support her sport, she also trains

and breeds horses, and coaches young riders.

"I'm probably not going to get rich and famous practicing law," she

decides. Rather, her lifelong dream is to compete at the level of an

Olympian.

"My goal isn't necessarily to be on an Olympic team," she says, "but

I really want to be of that caliber and make the list of

candidates."

Martin D. Stein, comedian

Martin Stein doesn't tell lawyer jokes. Well, okay, maybe one or two.

After all, he is a stand-up comic, and much of his material does draw on

his own professional life.

So, in his shtick, he pokes fun at himself.

Martin D. Stein, Mequon, a litigator by day and

stand-up comic by night, says some of the funniest people he's ever met

are lawyers. But he never, ever takes his shtick into the courtroom;

litigation is no laughing matter.

|

To wit: I'm a pretty good personal injury lawyer. I have my own

ambulance.

And: If I can't settle your case in 30 minutes or less, the next

whiplash is free.

Biggida boom.

Born and raised in Philadelphia and a graduate of Thomas M. Cooley

Law School in Lansing, Mich., Stein, 33, now lives in Mequon with his

wife, Pamela Kahn-Stein, a Wisconsin native who's also a lawyer. ("I'm a

cheesehead by marriage," says Stein.) Three years ago, he decided to

take a night course to learn how to perform stand-up comedy.

"I took the course not to become a stand-up comedian, but for my

trial skills," he says. "I wanted to be a little more animated. Trials

are so boring. And there are too many lawyers out there who take the

practice of law, and themselves, too seriously. Either they need a sense

of humor or a bowl of bran cereal."

As a final exam for the course, each student was given 10 minutes on

stage on amateur night at the Comedy Cafe in Milwaukee.

"I did pretty well," Stein says. And, lo and behold, the club began

booking him to do steady gigs.

His first gig was in July 1995. Since then, he's performed at a

number of clubs around the state and Milwaukee's Summerfest for the past

two years.

"I think comedy has made me a better lawyer," says Stein. "I'm much

quicker on my feet. I connect better with jurors. I can stand back and

look at being a trial lawyer more objectively."

Being a comic and a trial lawyer both require a high measure of

performance. Stein must be in complete control of an audience in both

venues - on stage and in a courtroom.

Has he ever crossed the line and slipped into his shtick in the

courtroom?

Litigation is no laughing matter, he says. "I take my job very

seriously. I don't go into a judge's chamber cracking jokes. And I've

never been told by a judge that I'm disrespectful in court."

Yet he believes there's room for lawyers to lighten up a bit, to lose

some of the formality, the stiffness, the officiousness that often

characterizes the profession.

"Some of the funniest people I ever met in my life are lawyers," he

says. But too often, as soon as they enter a courtroom, their humanity

is replaced by an air of self-importance.

"I don't want to end up as a lawyer who looks like he goes to sleep

in his blue suit and red tie," he says, borrowing from his act. "I want

to present myself in a more relaxing, engaging way."

Gerald Jolin, sculptor

As a small boy, Gerald Jolin would follow his father into the forest

near Shawano to help him size up trees that would be sold to lumber

companies. And sometime in his early school days, he learned to

carve.

Former Outagamie County Judge Gerald Jolin, now

residing in the Florida Keys, scratches his itch to carve with chisel

and mallet.

|

"I'd done that as a hobby way back," says Jolin, now 83. "I jocularly

say I worked my way through grade school by sculpting wooden guns and

trading them with my classmates for lunch."

But as he reached adulthood, Jolin was temporarily sidetracked by the

profession of law. He received a J.D. from the University of Wisconsin

Law School in 1940 and went into general practice in Hortonville. Three

years later, at age 29, he was elected judge in Outagamie County, the

youngest county judge ever elected in Wisconsin.

Jolin served on the bench for nine years and resigned to return to

private practice in Appleton. With four growing sons bound for college,

he could no longer afford to support his family on the wages of a county

judge.

While living in Appleton, he began to chisel tree trunks and branches

into sweeping, graceful sculptures.

He moved with his family to Houston to practice finance law in 1972,

at the height of the oil boom. And in 1979 he teamed up with a program

for the mentally handicapped in Michigan, developing woodworking

workshops for clients. Drawing on the principles of art therapy, Jolin

taught mentally handicapped adults how to build salable, wooden benches

from recycled wood. Over the next few years, 100-plus participating

clients produced more than 15,000 benches.

After retiring from law in the late 1980s, Jolin continued to sculpt.

He's donated many of his pieces to nonprofit groups, including hospices

and shelters for disadvantaged children. This past summer, he began

working on a sculpture for the Gray Panthers, carving a 14-inch-thick

palm tree that he salvaged from the Gulf coast in Texas. Also in late

August, Jolin and his wife, Marion, moved to the Florida Keys, where a

son lives aboard a houseboat.

Over the course of his legal career, Jolin has regarded his interest

in woodcarving as a necessary "left-brain, right-brain" diversion.

"You get an itch for a change," he says. "I certainly have had an

itch to carve. It comes back on you, like malaria. It rises up on you

again and again."

Gary Dalebroux, farmer

To call Gary Dalebroux's 500-acre homestead in Kewaunee County a

"hobby farm" is doing him a great disservice.

But it's his own choice of words.

"I always tell my clients that instead of golfing or fishing, I go

farming," Dalebroux says. "That's my time away to think, to relax, to

enjoy what I enjoy doing. That's why I call it a hobby farm."

Gary Dalebroux, Casco, relaxes by "going farming" on

his 500-acre homestead. Of his love for farming and the practice of law,

Dalebroux says one helps keeps him sane when the other has its bad

days.

|

Dalebroux really has never left the farm. All through school and into

law school at U.W.-Madison, he pitched in on the family farm, literally

a stone's throw from where he and his family now live. And when

Dalebroux and a law school classmate hung out a shingle after graduating

in 1975, he started up a dairy farm with his two younger brothers to

supplement his income.

But the rigors of running a law practice and a dairy farm were too

great. He quit farming and concentrated on his practice. For awhile.

"I missed the farming," he says. So in 1985 he started raising corn

and soybeans.

The bulk of his clients are farmers, naturally. "I understand their

business; I understand the problems they face. I talk their

language."

The oldest of six, Dalebroux, 46, is a self-confessed workaholic. He

rises before dawn and rides a bicycle seven miles along the county roads

to check his crops. By 7:30 a.m., he's changed into his pinstripes and

sits in his office in Casco. After office hours, back on the farm, he

often works past sunset. In springtime, it's not uncommon for him to be

planting corn until 3 a.m.

"Instead of bowling and coming home at 3 in the morning, I can come

home from farming at 3, and my wife doesn't wonder where I was."

Both the farm and the law practice have become family affairs. His

wife, Erika, a licensed title agent, runs the office. Their youngest

child, one-year-old Hope, already is thrilled by rides on the John Deere

tractor. Kim, 18, has spent plenty of her days picking rocks out of the

fields. And the oldest, Troy, 22, is now a law student himself at

U.W.-Madison.

Does Dalebroux prefer farming or lawyering?

"I love them both," he says. "There are times when farming presents

challenges difficult to accept. The weather's your biggest enemy.

Draught, rain ... it's depressing to see your hard work go for

nothing.

"Similarly, not everything goes right in a law practice. And getting

outdoors, seeing the fruits of your labor, that can offset the bad days

at the law office.

"One helps keep me sane when the other has its bad days."

Kurt Chandler is a writer and editor

in Wauwatosa.

Wisconsin

Lawyer