Most construction contracts presume that unanticipated changes sometimes happen, and permit changes to the contract price in those circumstances.

However, these terms typically require the party seeking the change (most often a contractor or subcontractor seeking additional money due to unanticipated issues) to establish a causal link between the change and the increased work needed, and thus price.

When projects are beset by numerous overlapping issues (for example, adverse weather issues, a design change, and unforeseen jobsite conditions), it can be very difficult to determine which event caused which portion of increased cost.

Kevin Long, Marquette 1992, is a partner with

Quarles & Brady LLP, Milwaukee, where he practices in commercial litigation with a focus on construction, real estate, and transportation related litigation.

Kevin Long, Marquette 1992, is a partner with

Quarles & Brady LLP, Milwaukee, where he practices in commercial litigation with a focus on construction, real estate, and transportation related litigation.

The Total Cost Method or modified Total Cost Method provides a manner for claimants to recover their full damages if they are able to establish four key criteria. While Wisconsin Courts have not directly adopted the Total Cost Method in any published decision, it has been approved in several other states, and regularly used in the right circumstances, particularly within the arbitration setting.

This, combined with Wisconsin’s general liberal rules with respect to manner of damages proof and deference to jury determinations, makes consideration of the Total Cost Method appropriate in any case where multiple factors cause delay to a generally blameless contractor or subcontractor.

A key to determining the applicability of the Total Cost Method or modified Total Cost Method, is whether either: (a) the contract provides for it (unlikely); or (b) there has been such a significant breach of the contract or change in circumstances that either an abandonment of the contract or a cardinal change is found to have occurred.

Very few form construction agreements permit holistic damages calculations, such as those derived from the Total Cost Method or the modified Total Cost Method. However, the common-law damages authority may in certain situations allow for the utilization of these methods.

Role of the Modern Changes Clause

Many construction commentators agree that “[t]he modern changes clause is indispensable to the efficiency of 21st century construction, because it creates the contractual flexibility needed to make the construction process ‘work’ and the clause stands at the center of the universe of construction contract risk allocation clauses that utilize the changes clause to adjust the contract as and when required.”[1]

The modern changes clause has allowed all parties to a construction contract to have greater flexibility within the contract, but has also created the potential for different measurements of relief afforded to contractors who are faced with unexpected jobsite conditions not caused by them.[2]

A measure of damages set forth in the verbiage of the changes clause may differ from the measure of damages awarded based on a contractual breach (either for failing to pay amounts due or failing to agree to requested change orders). Since the early 20th century virtually all construction contracts contain provisions allowing the owner the flexibility to unilaterally make or approve additive or deductive changes in the work and adjustments in contract time or price.[3]

The changes clause is a significant legal innovation[4] that allows contracting parties to alter the common law by agreement to achieve the following objectives:

- to jettison the bilateral common-law contract modification rules of “offer and acceptance” in favor of a more flexible approach under which an owner was authorized unilaterally to order changes within the contract's “scope” without prior consent of the Contractor, subject to adjusting the contract price accordingly;

- to control confusion over what constituted a “change” by requiring them to be formally issued in writing;

- to require consideration of whether a “change” involving public work was within the contract scope and not required by statute to be awarded by competitive bidding;

- to define the basis for equitable payment adjustment for the work as changed;

- to coordinate changes through design professionals to assure that the changes were compatible with design criteria, and traceable into the project's “as-built” condition;

- to limit claims for “extra work” to those for which the Contractor gave timely notice to the owner;

- to require the prompt performance of the change; and

- to remove the “change” from the ambit of the common-law breach of contract by substituting administrative adjudication and adjustment of disputes in place of formal court litigation.[5]

When are Breach of Contract Damages Available?

Only where a claim either is not redressable administratively “under the contract,” or arises out of a material breach of contract “outside of its general scope,” does the claim become subject to common-law breach of contract principles.

A material breach arising out of abuse of the changes clause has sometimes been labeled variously as (1) a “cardinal” change[6] or (2) an “abandonment” of the contract,[7] though in other cases, it is simply described as a material breach.[8]

The determination of whether an event constitutes a change “under” the contract (redressable administratively), “outside of” the specific scope but within the “general scope” of the contract (redressable administratively), or outside of the contract's “general scope” (redressable as a breach of contract), must be “analyzed on its own facts and in light of its own circumstances.”[9]

In affirming the judgment of a trial court in favor of the contractor who pursued a damages claim under the Total Cost Method, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled that the “changes and extra work” clause was inapplicable because (1) the construction manager had never invoked the clause by issuing a change order or direction for “extra work,” and (2) the contractor was not precluded by the “changes and extra work” clause from pursuing a claim for breach of contract damages computed under the “total cost” method.[10]

Thus, modern change clauses will, by their terms, typically preclude the use of a Total Cost Method for calculating damages, but where the owner (or upstream contractor) by its actions has committed a material breach of the contract, additional damages theories including the Total Cost Method may be utilized in the right circumstances. Under the law of most jurisdictions, the TCM may be utilized where there is proof that (1) the nature of the particular losses make it impossible or impractical to determine them with a reasonable degree of accuracy; (2) the plaintiff’s bid or estimate was realistic; (3) its actual costs are reasonable; and (4) the plaintiff was not responsible for the added costs.[11]

AAA Panel embraces TCM on Project with Severely Impacted Schedule

In a recent AAA arbitration, a distinguished three-arbitrator panel applied the Total Cost Method to provide an appropriate remedy for a subcontractor, after it found:

- the promised construction schedule around which the sub planned its bid and manpower was scrapped by the general contractor and owner;

- mid-project, the subcontractor was presented with a “re-baseline schedule” that was organized differently than the original schedule and failed to account for the delays and impacts that the sub had already confronted;

- the re-baseline schedule was abandoned two months later in favor of 3-Week-Ahead schedules that the panel described as haphazard; and

- shortly before the bargained-for substantial completion date in the subcontract, the general ordered the sub to commit to a mechanical completion deadline that the panel described as “universally recognized as unachievable, though still used by [the general contractor] to justify descoping portions of the subcontractor’s work.”

The panel concluded that none of the material and essential elements of the deal underlying the subcontract were honored, that the failure of the general contractor to abide by the bargained-for project Construction schedule was a material breach of the Subcontract.

Moreover, it found that the general contractor’s failure to acknowledge the obvious and reasonably known impacts to the subcontractor and develop some form of reasonable consideration for the materially changed conditions exacerbated the breach.

Furthermore, the panel concluded that the general contractor’s failure to pay the subcontractor for its work performed constituted an additional breach. In summary, the panel concluded that “[t]he overwhelming evidence persuades the panel to conclude that requiring [the Subcontractor] to document its actual productivity losses through the Subcontract’s COR process (as [the GC] deemed appropriate) would never compensate [the subcontractor] or its actual losses caused by the impacts and delays on the project.”

The panel allowed for the use of the Total Cost Method after finding

- The GC’s breach regarding project schedule pervaded the entirety of the subcontractor’s work;

- overwhelming evidence demonstrated that the subcontractor’s bid was realistic and reasonable;

- the preponderance of the evidence compelled the panel to conclude that the subcontractor’s project costs were reasonable; and

- the panel concluded that the subcontractor was not responsible or the extra expenses it incurred at the project.[12]

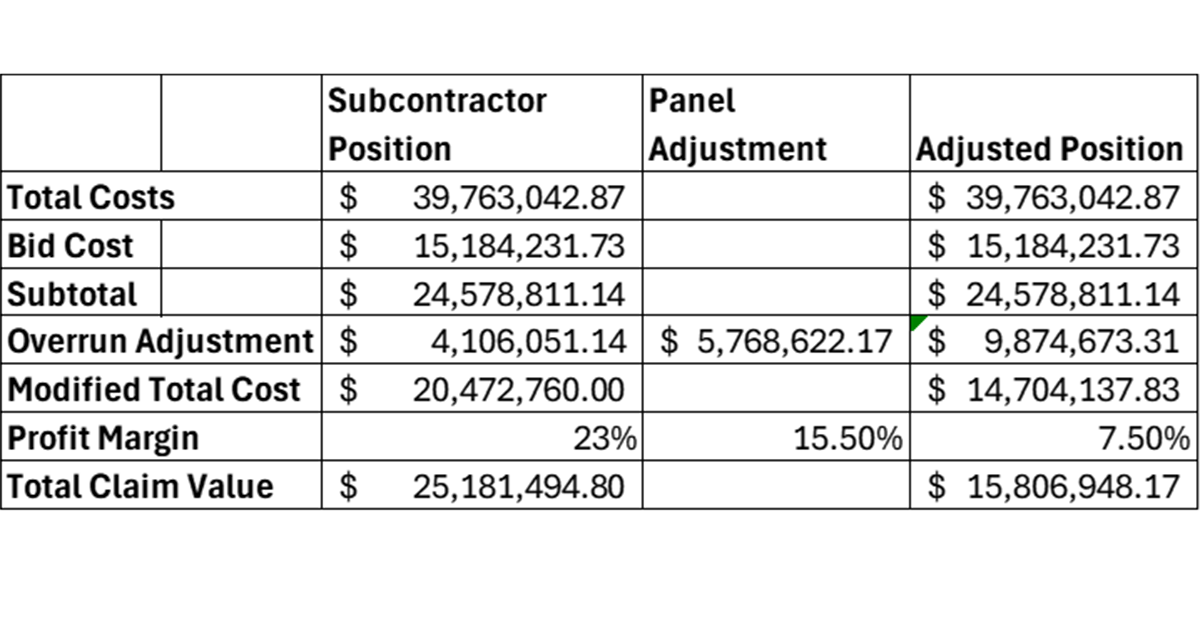

The panel, applying the TCM under Wyoming law, first determined the (1) Subcontractor’s Total Costs, and reduced that amount by (2) the bid cost, as well as (3) the Cost overruns. Thereafter the panel applied a profit margin to determine the subcontractor’s claim value. The amounts were calculated as follows in Figure 1:

The panel made two adjustments to the subcontractor’s claim, the overrun adjustment, and the profit margin percentage. Notably, neither the subcontractors’ acknowledgment that an overrun adjustment was appropriate, nor the panel’s doubling of that adjustment were enough to dissuade the panel from concluding that “the Subcontractor was not responsible or the extra expenses it incurred at the Project.” The panel’s conclusion is consistent with other courts’ interpretation of this element.[13]

Application Under Wisconsin Law

While it is unclear if the same result would occur if this claim were brought under Wisconsin law, there is nothing under Wisconsin law that explicitly precludes the use of the Total Cost Method. In fact, the method is not mentioned in any published decision.

We know from review of appellate court briefing that a subcontractor used the theory in

Downey v. Bradley Center Corp., 188 Wis. 2d 435, a case involving cost overruns on the construction of the Bradley Center in the 1980s. There, the subcontractor’s expert switched to the Total Cost Approach late in the litigation, and the general contractor and owner objected, claiming that the trial court should have prevented the opinion from being presented at trial. The trial and appellate court rejected the motions in limine, determining that the trial court’s discretionary decision allowing the opinion was not reversible where the court determined that the late change did not prevent the general contractor from defending against the subcontractor’s claim. It does not appear that any party argued that the method itself was inappropriate. Rather the basis for the motion was the late change.

In Wisconsin, damages for breach of contract aim to compensate the non-breaching party for their losses, essentially putting them in the same position they would have been in had the contract been fulfilled.

This compensation can include direct damages, such as the cost of goods or services, as well as incidental and consequential damages. Wis. J.I. (Civil) 3710 Wisconsin Civil Jury Instruction 3710, Consequential Damages for Breach of Contract, states “The law provides that a person who has been damaged by a breach of contract shall be fairly and reasonably compensated for his or her loss. In determining the damages, if any, you will allow an amount that will reasonably compensate the injured person for all losses that are the natural and probable results of the breach.”

Application of this default standard would allow nonbreaching parties to be made whole, but many construction contracts contain waivers of consequential damages.

This article was originally published on the State Bar of Wisconsin’s

Construction and Public Contract Law Section Blog. Visit the State Bar

sections or the

Construction and Public Contract Law Section web pages to learn more about the benefits of section membership.

Endnotes

[1] Bruner & O’Connor on Construction Law, § 4:2. The modern changes clause—Its purposes and objectives (citing Crowell and Johnson, A Primer on the Standard Form Changes Clause, 5 Wm & Mary L.Rev. 550 (1967))

↩

[2] Bruner & O’Connor on Construction Law, § 4:2.

↩

[3]

Id.

↩

[4] Bruner & O’Connor on Construction Law, § 4:2. (citing Crowell and Johnson, A Primer on the Standard Form Changes Clause, 5 Wm & Mary L.Rev. 550 (1967))

↩

[5] Bruner & O’Connor on Construction Law, § 4:2. The modern changes clause—Its purposes and objectives.

↩

[6]

See J.A. Jones Const. Co. v. Lehrer McGovern Bovis, Inc., 10 Nev. 77, 89 P.3d 1009, 100 (2004).

↩

[7]

See O’Brien & Gere Technical Services, Inc. v. Fru-Con/Fluor Daniel Joint Venture, 380 .3d 447, 455-456 (8th Cir. 2004)

↩

[8]

See infra, AAA Panel decision in Kenny Electric v. Casey Industrial, AAA Case No. 01-23-0001-2574.

↩

[9] Bruner & O’Connor on Construction Law, § 4:2.

↩

[10]

Bagwell Coatings, Inc. v. Middle South Energy, Inc., 797 F.2d 1298 (5th Cir. 1986)

↩

[11] Aaen, “The Total Cost Method of Calculating Damages in Construction Cases,” 22 Pacific L. Review 1185 (citing

WRB Corp. v. United States, 183 Ct. Cl. 409, 46 (1968).

↩

[12]

Kenny Electric v. Casey Industrial panel applying

Frost Constr. Co. v. Lobo, Inc., 951 P.2d 390, 397-98 (Wyo. 1998).

↩

[13] See Aaen, 22 Pacific Law Review at pp.1202-03 (citing

Nebraska Public Power District v. Austin Power, Inc., 773 F.2d 960 (8th Cir. 1985) (If the first element of the bifurcated test for whether the increased costs were not caused by the plaintiff, is not met, the plaintiff could recover under the modified total cost method, with the jury deducting the amount for which the plaintiff was responsible).

↩