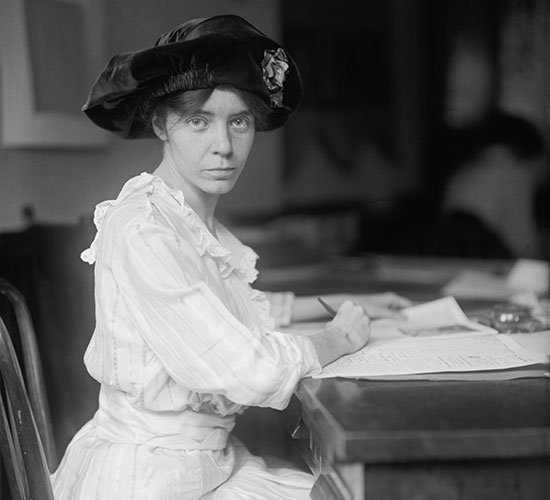

Crystal Catherine Eastman (1881-1928) with Amos Richards Eno Pinchot (1873-1944), a lawyer and progressive reformer. Eastman, a suffragist, Milwaukee resident, and lawyer, helped coathor the original draft of the ERA. Photo: Library of Congress

Every democracy must persistently question whose voices are left out of the national discourse. Just over a century ago, on August 18, 1920, the United States ratified the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and thereby granted suffrage to women.1 While this marked an important milestone toward enfranchising all Americans, many women of color would still remain disenfranchised through other forms of voter suppression. To date, the 19th Amendment constitutes the U.S. Constitution’s only explicit reference to gender.

So, what additional strides toward gender equality have been made since 1920? The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is one of those efforts. Although it has never been officially ratified, it is enjoying renewed attention after several states recently voted to ratify it.2 This article explores the ERA, its historical pedigree, and other efforts legal strategists have pursued to achieve fuller gender equality under the law.

What Is the ERA?

In its current form, the ERA provides as follows:

“Section 1: Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.

Section 2: The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Section 3: This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification.”3

If adopted, the ERA would become the 28th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This is numerically fitting given that the ERA could be characterized as a corollary to the 14th Amendment, which guarantees birthright citizenship and equal protection of the laws.

The ERA’s spare language belies its powerful mandates. Like the Reconstruction Amendments, it authorizes Congress to promulgate legislation to enforce its terms. It also does not contain a citizenship requirement, which suggests that even undocumented individuals may benefit from its protections. As written, the ERA also grants the states and federal government a grace period of two years to prepare for its effective date. This would give states and municipalities time to reevaluate the laws and regulations, which could be invalidated or superseded.

Of course, like any constitutional amendment, the ERA must be ratified according to Article V of the Constitution. According to the Constitution, two-thirds of both chambers of Congress must approve an amendment, followed by three-fourths of the states’ legislatures. This means that at least 38 state legislatures are needed.

Now We Can Begin

The quest for ratification really began the moment that the 19th Amendment was adopted. Two women were particularly instrumental early on: Crystal Eastman and Alice Paul. Eastman was a suffragist, a Milwaukee resident, and even a member of the Wisconsin bar.4 Once the 19th Amendment was ratified, Eastman published an essay titled “Now We Can Begin,” which persuasively urged ratification of the ERA.5 Eastman also helped coauthor the original draft of the ERA.6

Alice Paul was also a suffragist and ERA coauthor. She possessed several degrees, including a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania and law degrees from American University (in Washington, D.C.).7 Paul is credited as the face of the ERA because she formally introduced it in Seneca Falls, N.Y., on the 75th anniversary of the 1848 Women’s Rights Convention.8

The state of Wisconsin has also played a pivotal role in the ERA fight. Wisconsin ratified the ERA on April 26, 1972, 49 years after Paul introduced the ERA, making the state a very early supporter.9

This is unsurprising given Wisconsin’s progressive track record. For example, Wisconsin was the first state to ratify the 19th Amendment in 1919.10 Then, on June 21, 1921, Wisconsin became the first state to enact an equal rights law, which guaranteed that “women shall have the same rights and privileges under the law as men in the exercise of suffrage, freedom of contract, choice of residence for voting purposes, jury service, holding office, holding and conveying property, care and custody of children and in all other respects.”11

Alice Paul herself took note and wrote: “This makes Wisconsin the only spot in the United States where women have, or ever have had since the beginning of our country, full equality with men.”12 Regarding other sex equality rights, Wisconsin also became the first state to outlaw workplace discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.13

A vocal leader of the twentieth century women’s suffrage movement, Alice Paul (1885-1977), suffragist, lawyer, and coauthor of the ERA, is credited as the “face of the ERA” because she introduced it in Seneca Falls, N.Y., on the 75th anniversary of the 1848 Women’s Rights Convention. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Glass negative,1915.

Opposition to the ERA

Eastman and Paul were responsible for drafting the ERA, but not all women were staunch supporters. Phyllis Schlafly, a conservative firebrand, emerged as the face of its opposition movement. A native Missourian, and self-described “housewife,” Schlafly earned a master’s degree from Radcliffe College and later graduated 27th in her class of 186 at the Washington University School of Law.14

In Schlafly’s view, the ERA harmed women’s interests. Total equality, she argued, eviscerated the favorable distinctions women were entitled to – such as exemption from the draft.15 To that end, she founded the STOP ERA organization in October 1972.16 Her mobilization efforts were so successful that, in addition to stanching new state support, Idaho, South Dakota, Nebraska, Tennessee, and Kentucky voted to rescind their previous votes in favor of ratification.17

Among her many notable qualities, Schlafly is remembered for delivering the following line at public appearances: “I want to thank my husband, Fred, for letting me come here,” because, she said, she knew “it irritate[d] women’s libbers more than anything else.”18 Schlafly passed away in 2016 at the age of 92, leaving behind a legacy as controversial as it was effective.19

Fourteenth Amendment Litigation

Gender equality advocates also sought full equality under existing legal mechanisms. In 1962, the President’s Commission on the Status of Women (PCSW) recruited Pauli Murray, a noted constitutional scholar, to develop alternative arguments to achieve gender equality.20 Murray responded with a groundbreaking proposal to litigate the issue of gender equality under the 14th and 5th Amendments.21 Murray’s proposal urged courts to adopt a heightened reasonableness standard, which, in theory, invalidated arbitrary gender distinctions.22 Murray’s involvement is important for another reason: She was Black. Her invaluable contributions symbolize the vital role that people of color – especially women – have had in every major social movement in the United States. From suffrage to Selma to Stonewall, women of color have always been catalysts of change in the United States.

Murray’s 14th Amendment proposal proved persuasive. During the 1970s, gender-discrimination jurisprudence developed quickly. In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court, for the first time, struck down a gendered law on Equal Protection Clause grounds.23 The case, Reed v. Reed, involved an Idaho law that provided that men must be preferred to women in the selection of estate administrators.24 Then-professor Ruth Bader Ginsburg coauthored the brief in support of striking down the law.25 Ginsburg listed Murray as a coauthor in recognition of her efforts in developing the strategy.26

After ratifying the 19th Amendment, on June 21, 1921,

Wisconsin became the first state to enact an equal

rights law.

The Reed case foreshadowed a decade of gender-equality wins at the Court. Over the next several years, the Court would invalidate gendered laws on topics ranging from the right to serve on juries27 to access to 3.2 percent beer.28 In some instances, sympathetic male plaintiffs were sought so that the all-male Supreme Court could identify more easily with the party behind the case. Thus, ironically, important gender-equality precedent was based on discrimination against men, not women. For example, in Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, a widower was denied survivors’ benefits that would have been available to him if he had been female.29 The Court struck down that law as unjustifiably discriminatory.30

The ultimate goal of this Equal Protection Clause litigation was to classify gender as a suspect class subject to strict-scrutiny protection. In 1973, that question came squarely before the Court in the case of Frontiero v. Richardson.31 The case involved a married female Air Force lieutenant who sought a dependent’s allowance to help care for her husband.32 Frontiero was denied this money but would have been eligible for it if she had been male.33 In addition to urging the Court to strike down that rule, Frontiero also asked the Court to adopt strict scrutiny for gender-based classifications. Four justices acceded to that proposal, and so it failed by a single vote. It was not until 1996 that the Supreme Court would adopt intermediate scrutiny in another landmark case, United States v. Virginia (sometimes colloquially referred to as “the VMI case” because the Virginia Military Institute also was a defendant).34

The world lost a titan in October 2020 when Justice Ginsburg passed away. Her career was remarkable and full of symbolism. For example, it was she who argued the Frontiero case in front of the U.S. Supreme Court on Jan. 17, 1973, one year to the day after Congress sent the ERA to the states for ratification and only five days before the Court would hand down its decision in Roe v. Wade.35 And in 1996, it was Justice Ginsburg who delivered the Court’s opinion in United States v. Virginia.

Several people watch as Governor Patrick Lucey, seated at desk, signs the Equal Rights Amendment. Lloyd A. Barbee

(left), Marlin Schneider, two unidentified people, Midge Miller (center), unidentified woman, Mary Lou Munts (right),

David Clarenbach (far right). Photo: Wisconsin Historical Society, ID 97430.

Is the ERA Still Needed?

According to a January 2020 poll, public support for the ERA hovers at 75 percent.36 Americans thus mostly agree that the ERA is a positive measure. Perhaps surprisingly, its support is approximately equal between the sexes.37

But public support does not resolve whether it remains a necessary legal remedy. To be sure, American women enjoy far more legal protection today than they did in 1923. Protections such as Title VII, Title IX, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, intermediate scrutiny for gender-based classifications, and constitutional access to abortion were aspirational at best when the ERA was introduced. This has led some people to question whether a constitutional amendment would be superfluous and even whether a legal remedy may be the appropriate avenue for achieving gender equality. According to some, statutes and amendments cannot directly change society’s perspective on sexism, the root issue that must be solved.

ERA proponents might argue the opposite – contending that the ERA is needed now more than ever to solidify the past century’s hard-won gains, which, some people argue, have seen erosion at the margins. Reproductive freedoms are one example. Furthermore, Supreme Court precedent can itself be overruled. Cementing gender equality as a constitutional amendment would be the only way to ensure that the Court would be obligated to uphold such protections. Interestingly, because the ERA authorizes Congress to enforce its provisions against the states, this amendment would go much further than any previous statute or court ruling has.

Current Status of the ERA

The deadline to ratify the ERA expired in 1982. At that time, it failed by just three states’ votes. Recently, Nevada, Illinois, and Virginia voted for ratification.38 This means that 38 states have voted to ratify the ERA at one time or another. Whether the votes of the five states that voted to rescind their support are valid is currently being litigated.

In early 2020, the House of Representatives voted to remove the ratification deadline for the ERA.39 This has generated controversy and uncertainty. On Dec. 19, 2019, Alabama, South Dakota, and Louisiana jointly sued the U.S. archivist, David Ferriero, to prevent ratification of the ERA.40 This lawsuit, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama, argues that the ERA is invalid because 1) the ERA’s ratification deadline has passed; and 2) the five states’ votes to rescind support were valid, which would leave the ERA short of the 38-state threshold.41

Ironically, important gender-equality precedent was based on discrimination against men, not women.

In response, on Jan. 30, 2020, Illinois, Nevada, and Virginia also filed suit against Ferriero, this time in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia and to compel ratification.42 These states argue that the ERA is valid because 38 states have voted, at one time or another, to ratify the ERA, and the U.S. archivist lacks discretion to decide whether an amendment was timely.43 This argument assumes that the House’s vote to repeal the 1982 deadline is valid. Both suits are ongoing.

Although the validity of the ERA is being litigated, even some of its fiercest proponents have argued that starting fresh would be a better option. Justice Ginsburg publicly remarked in early 2020 that starting the ratification process anew would be a better option than litigating the ratification deadline and whether states can legally rescind their ratification votes.44

Conclusion

It is numerically fitting that the ERA would, if ratified, become the 28th Amendment to the Constitution. After all, many consider it as a corollary to the 14th Amendment. For years, the ERA has remained the elusive crown jewel among American feminists. In sports parlance, the path to full equality among the sexes can be properly characterized as a race. However, this race is neither a sprint nor a marathon: It is a relay. As members of each generation press toward full equality, they hand off their successes to the next generation so that they may manifest the vision that began in Seneca Falls in 1923.

Meet Our Contributors

You have an unusual name. How did you come by it?

It’s a fair question and one that I get often: “Is Storm your real name?” After all, my two older brothers are named James and Christian. How’s that for contrast? I wish there was a dramatic story behind it, but it’s really as simple as me having strong Scandinavian roots. Storm is a name sometimes given to Norwegian boys. (With a last name like Larson, go figure.)

It’s a fair question and one that I get often: “Is Storm your real name?” After all, my two older brothers are named James and Christian. How’s that for contrast? I wish there was a dramatic story behind it, but it’s really as simple as me having strong Scandinavian roots. Storm is a name sometimes given to Norwegian boys. (With a last name like Larson, go figure.)

Storm is now my first name, but it wasn’t always that way. From birth to 2 years old, my name was Benjamin Storm Larson. But I’m told that next to no one called me Ben or Benjamin growing up. Instead, everyone opted to call me by my then-middle name, Storm. This practice became so ubiquitous that my parents decided to make it official and, at the age of 2, took me to La Crosse County Circuit Court and had it changed to what it is today: Storm Benjamin Larson.

According to my parents, on the date it was changed, Judge Ramona Gonzalez was the presiding judge. Perhaps foreshadowing my current career, she and I engaged in dialogue. I’m told she asked me: “What’s your name, little boy?” To which I responded: “My name is Storm Larson.” I have no personal recollection of this interaction but, as you can see, it foreshadowed my current career as a litigator.

Storm B. Larson, Bell Moore & Richter SC, Madison.

Become a contributor! Are you working on an interesting case? Have a practice tip to share? There are several ways to contribute to Wisconsin Lawyer. To discuss a topic idea, contact Managing Editor Karlé Lester at (800) 444-9404, ext. 6127, or email klester@wisbar.org. Check out our writing and submission guidelines.

Endnotes

1 The 19th Amendment, Nat’l Archives, (last reviewed May 14, 2020).

2 Timothy Williams, Virginia Approves the E.R.A., Becoming the 38th State to Back It, N.Y. Times (Jan. 15, 2020).

3 Equal Rights Amendment, NOW, (last visited Jan. 4, 2021).

4 Amy Aronson, Crystal Eastman: A Revolutionary Life (2019).

5 Id.

6 Id.

7 Penn People: Alice Paul 1885-1977, Penn Univ. Archives & Records Ctr., (last visited Jan. 4, 2021).

8 Tracy A. Thomas, From 19th Amendment to ERA, Am. Bar Ass’n (Jan. 22, 2020).

9 Robin Bravender, Congress Renews Push for Equal Rights Amendment, Wis. Exam’r (Nov. 19, 2019).

10 Meg Jones, Similarities Between Suffrage Movement a Century Ago and Today’s Protests, Milwaukee J. Sentinel (Aug. 14, 2020).

11 Erika Janik, Nation’s First Equal Rights Bill Passed in 1921 in Wisconsin, Wis. Pub. Radio (June 19, 2017).

12 Id.

13 Wisconsin a State of Firsts for Rights of Women, LGBT, Madison.com (Aug. 20, 2017).

14 Douglas Martin, Phyllis Schlafly, ‘First Lady’ of a Political March to the Right, Dies at 92, N.Y. Times (Sept. 5, 2016).

15 Patricia Sullivan, Phyllis Schlafly, a Conservative Activist, Has Died at Age 92, Wash. Post, Sept. 5, 2016.

16 Martin, supra note 14.

17 Danielle Kurtzleben, House Votes to Revive Equal Rights Amendment, Removing Ratification Deadline, Nat’l Pub. Radio (Feb. 13, 2020).

18 See Martin, supra note 14.

19 Serena Mayeri, Constitutional Choices: Legal Feminism and the Historical Dynamics of Change 92 Calif. L. Rev. 755, 762-63 (2004).

20 Id. at 763.

21 Id. at 781-82.

22 Id. at 763-64.

23 Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971).

24 Id.

25 See Mayeri, supra note 19, at 814-15.

26 Id.

27 Edwards v. Healy, 421 U.S. 772 (1975).

28 Craig v. Boren, 429 U.S. 190 (1976).

29 420 U.S. 636 (1975).

30 Id.

31 411 U.S. 677 (1973).

32 Id.

33 Id.

34 518 U.S. 515 (1996).

35 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

36 Marcyclaire Dale & Jocelyn Noveck, AP-NORC poll: Most Americans Support Equal Rights Amendment, Associated Press (Feb. 24, 2020).

37 Id.

38 Bill Chappell, Virginia Ratifies the Equal Rights Amendment, Decades After The Deadline (Jan. 15, 2020).

39 See Kurtzleben, supra note 17.

40 Kim Chandler, 3 States File Lawsuit Seeking to Block ERA Ratification, Associated Press (Dec. 18, 2019).

41 Id.

42 Ryan W. Miller, 3 State Attorneys General Sue to Recognize ERA as 28th Amendment, USA Today (Jan. 30, 2020).

43 Id.

44 Russell Berman, Ruth Bader Ginsburg Versus the Equal Rights Amendment, The Atlantic, Feb. 16, 2020.

» Cite this article: 94 Wis. Law. 24-29 (March 2021).