In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, lawyers expected a wave of employment law litigation. While some litigation has already materialized, more is certainly on the horizon. This update to “The New Wave of Litigation: An Early Report on COVID-19 Claims” (Wisconsin Lawyer, June 2020) provides a broad overview of claims and cases seen to date and ones anticipated in the near future.

Workplace Safety Claims

Although the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (the “OSHA Administration”) has yet to issue any pandemic-specific guidance related to workplace safety, that has not prevented employees from filing complaints and the OSHA Administration from conducting investigations and issuing citations and corresponding penalties under the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA Act) related to COVID-19.

As of early December 2020, more than 260 citations for violations of the OSHA Act have been issued by the OSHA Administration related to COVID-19, ranging in monetary penalties from $0 to $32,956 and totaling in excess of $3.5 million.1 Three of these citations were issued against Wisconsin entities.2 The majority of OSHA citations to date have dealt with respiratory protection, the recording and reporting of occupational injuries and illnesses, personal protective equipment, and failure to abide by the general duty clause.3 Under the OSHA Act, employers have a general duty to furnish a place of employment free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause the death of or serious physical harm to employees.4

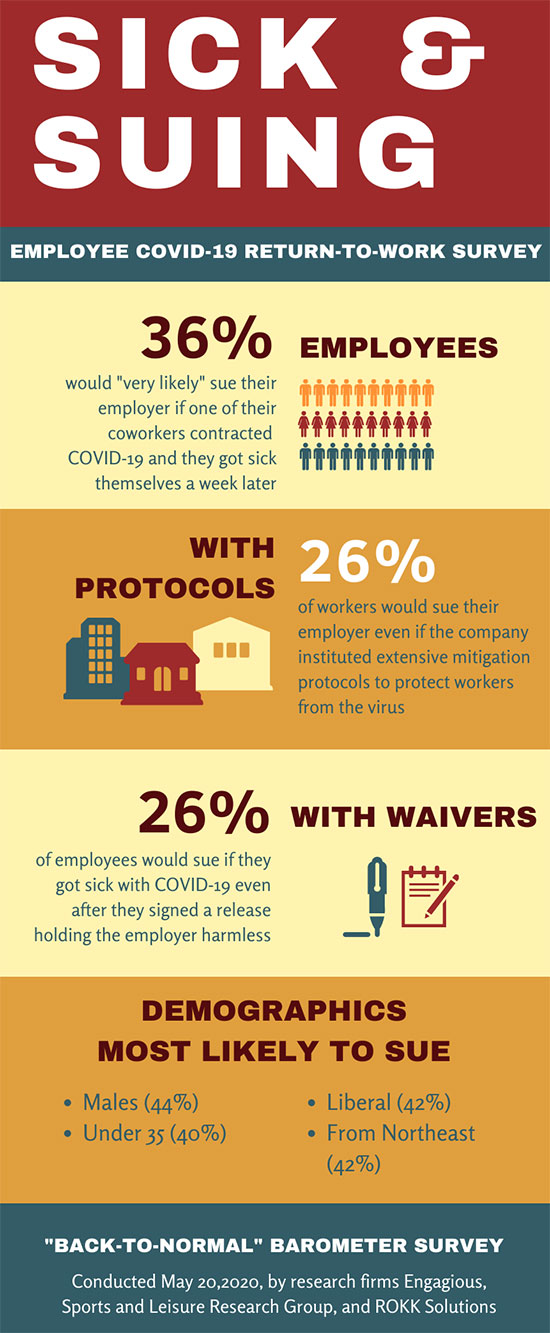

It is highly unlikely that claims like these, related to employees’ safety in the workplace as it relates to COVID-19, will disappear any time in the near future. A recent survey (see accompanying infographic) showed that approximately one-third of employees would sue their employer if they contracted COVID-19 at work as a result of a coworker being sick.

The End of FFCRA? What’s Next?

Since it became effective on April 1, 2020, employers have been dealing with various leave requests under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA).5 Under the FFCRA, private employers with fewer than 500 employees were required to provide certain types of paid sick leave and expanded paid family and medical leave.6 However, this leave entitlement was scheduled to sunset on Dec. 31, 2020, and as of this writing, no expansion of this leave has been proposed by Congress, signed by the President, or enacted into law. Therefore, while employers might no longer have to comply with the FFCRA’s complicated provisions, they potentially face lingering claims under the FFCRA, as well as new and uncertain claims under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), and the state equivalents of such laws.

If employees either sick with COVID-19 or caring for someone with COVID-19 no longer have leave protections under the FFCRA, employers will need to evaluate whether their employees are entitled to leave under the FMLA, the ADA, or state law equivalents. The FMLA provides up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave7 to eligible employees8 of covered employers9 for qualifying reasons, among them the following: 1) a serious health condition that makes the employee unable to perform the functions of his or her job; and 2) to care for the employee’s spouse, son, daughter, or parent who has a serious health condition. Although the definition of a serious health condition relies on detailed statutory and regulatory evaluation,10 it is likely that coronavirus will often qualify as such. Therefore, it will be incumbent on employers to carefully track whether they are covered employers, which employees are eligible for FMLA leave, and why a particular employee needs leave and to provide timely eligibility notices and other documentation to such employees.

Additionally, the ADA and the Wisconsin Fair Employment Act (WFEA) prohibit discrimination based on disability and require reasonable accommodations for disabilities, including unpaid leaves of absence. The ADA defines disability as “(A) a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities of such individual; (B) a record of such an impairment; or (C) being regarded as having such an impairment.”11 Whether coronavirus is a disability is likely to be a hotly litigated point and, given the virus’s different effects on each individual, may depend on the specific facts and circumstances of each case. Additionally, some employees might have other disabilities that make their in-person attendance at work more dangerous during a pandemic, and therefore they might also need accommodations. As companies continue to trend back toward “normal” work requirements, employers will need to be continually cognizant of potential accommodations, including continued remote work, limited travel, and personal protective equipment. Failure to provide such accommodations could result in additional claims.

Before the pandemic, many employers denied work from home as an accommodation on grounds that an employee would not be able to perform the essential functions of the job remotely. After months of working from home, that analysis may have changed. While the EEOC has taken the position that employers are still entitled to engage in an interactive process to determine whether working from home will actually accommodate the disability and whether there is another effective accommodation, it has also stated that “the temporary telework experience could be relevant to considering the renewed request [for a work from home accommodation]” and that “the period of providing telework because of the COVID-19 pandemic could serve as a trial period that showed whether or not this employee with a disability could satisfactorily perform all essential functions while working remotely, and the employer should consider any new requests in light of this information.”12 Therefore, moving forward, employers must carefully consider whether working from home is a necessary and available disability accommodation.

Infographic by Michaela Paukner/Wisconsin Law Journal

Work from Home as a Wage and Hour Concern

Companies may face lawsuits related to work from home expenses incurred by employees, such as phone and internet service. Unlike California and Illinois, Wisconsin does not have an expense-reimbursement statute. However, under the Fair Labor Standards Act, such expenses may not cut into the minimum wage that a nonexempt employee is legally owed without violating federal law.

Additionally, employers must ensure that they are properly tracking the hours worked by their nonexempt employees while they work from home. On Aug. 4, 2020, the Department of Labor issued a Field Assistance Bulletin13 outlining how employers must exercise reasonable diligence in providing reporting mechanisms, encourage accurate reporting, and compensate employees for all hours worked.

WARN Act and WBCL Claims

Under the Federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act (WARN) and the Wisconsin Business Closing and Mass Layoff Law (WBCL), certain companies are required to provide employees with 60 days’ written notice before a business closing or mass layoff. As companies continue to face operational restrictions as a result of governmental mandates and general declines in business as a result of individual hesitation, they may be faced with the need to downsize their staffs. If they are unable to provide the required 60-day notice, they may face steep damages and penalties, unless they can show that they are entitled to an exception. One such exception is the “unforeseeable business circumstance” whereby the circumstances that caused the business closing or mass layoff were not reasonably foreseeable at the time that the 60-day notice would have been required.14

It is important to note that, even if an employer is entitled to an exception to WARN or the WBCL, such as an “unforeseen business circumstance,” they are still required to give as much notice as possible.15 The alleged failure to give such notice has resulted in additional lawsuits, claiming that employers should have known earlier that a layoff was imminent. For example, Calero v. Fanatics Inc.16 is a proposed class action, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida, that alleges the company provided only four days’ notice to the employees before terminating their employment, despite the fact that the company allegedly knew months earlier that a mass layoff would likely be necessary. Therefore, to avoid costly class action litigation and potential damages and penalties, companies must realistically evaluate their future viability and notify employees, union officials, and governmental entities as soon as practicable of impending mass layoffs and plant closures.

Conclusion

There is little doubt that there will continue to be substantial employment litigation relating to COVID-19. It is imperative that companies, employees, and their counsel stay updated on such legal developments.

Cite to 94. Wis. Law. 43-45 (January 2021).

Endnotes

1 www.osha.gov/enforcement/covid-19-data/inspections-covid-related-citations.

2 Id.

3 www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/covid-citations-guidance.pdf.

4 29 U.S.C. § 654.

5 Pub. L. No. 116-127 (March 18, 2020); 29 C.F.R. pt. 826.

6 29 C.F.R. § 826.10; 29 C.F.R. § 826.20; 29 C.F.R. § 826.40.

7 29 U.S.C. § 2612.

8 29 U.S.C. § 2611(2).

9 29 U.S.C. § 2611(4).

10 29 U.S.C. § 2611(11); 29 C.F.R. § 824.113.

11 42 U.S.C. § 12102(1).

12 www.eeoc.gov/wysk/what-you-should-know-about-covid-19-and-ada-rehabilitation-act-and-other-eeo-laws.

13 www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/WHD/legacy/files/fab_2020_5.pdf.

14 20 C.F.R. § 639.9(b).

15 20 C.F.R. § 639.9.

16 No. 8:20-cv-02114.