As pure and abstract as we’d like the operation of justice to be, we all know the practice of law is embedded within an inherently unequal society, and that our work is exacerbated by and perpetuates severe systemic, institutional, and interpersonal inequity.

Conversations around power, inequality, and oppression can sometimes be difficult and uncomfortable, but they are valuable and necessary, in order to examine the theories of social interaction and change that underlies our work.

The Interactions of Status, Rank, and Power

I recently participated in community lawyering training offered by the Shriver Center on Poverty Law in Chicago.

One session explored concepts of identity, power, and difference that come up in the process of serving vulnerable communities.

We looked at three articles by Leticia Nieto and Margot Boyer that were published over a decade ago in Colors NW Magazine and later expanded in the book, Beyond Inclusion, Beyond Empowerment: A Developmental Strategy to Liberate Everyone.1

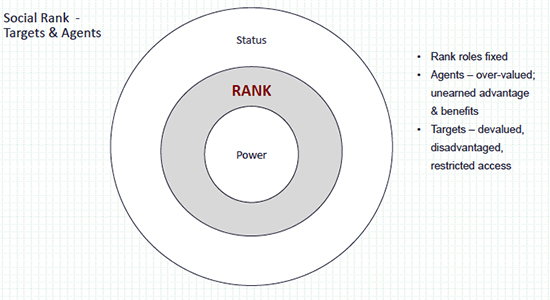

The writers present an interesting way to approach the topic. Nieto and Boyer start by delineating three concepts that tend to get muddled in some conversations around oppression: power, rank, and status, as separate aspects of social interaction. Like an onion,

status is the outermost layer, the one that is easiest for other people to see and the one we are most likely to be aware of, rank refers to the system of valuing people differently depending on certain social memberships, and power is the innermost layer, related to the core of our being.2

The authors describe the center of the model – personal “power” – as the connection an individual has to something greater than themselves, to history or the divine, a potential resource that resides at our innermost being that anyone can access.

“Status” operates at the most superficial level of interaction, easily observable, and can characterize the modes of behavior or posturing people employ in different settings:

High-status behavior is marked by a dominant or assertive posture and verbal messages of … leadership … or knowledge. Low-status behavior is marked by a submissive or passive posture, and verbal messages of agreement, compliance, acceptance, and support. Both high- and low-status moves can be useful in some situations or destructive in others – these are fundamental modes of behavior, not good or bad in themselves.3

“Rank” represents the ways individuals are valued differently based on innate qualities, a complex concept that can be thought of as an aspect of the culturally conditioned behavior of sorting, which underlies interpersonal dynamics. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Status, rank, and power, and their interactions with targets and agents. Used with permission from the Shriver Center on Poverty Law, Chicago.

In this model, “power” is a potential resource available to all people, “status” is an externally conferred position – a fluid and changing dynamic, but “rank” is a more fixed role, with a variety of conscious and subconscious social consequences.

This makes rank a worthwhile concept to examine and investigate how it might be operating in relationships and formal settings.

Using ADDRESSING

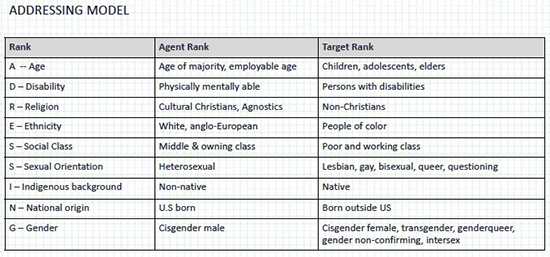

Pamela Hayes developed the acronym ADDRESSING, to think about nine different categories into which people in American society are sorted.4 Individuals can be identified as either agents or targets in each category. Those in the “agent” category receive advantage and privilege, and those in the “target” membership are vulnerable to disadvantage and oppression. Take a moment to tally up your memberships in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Categories into which people in American society are sorted.5 Used with permission from the Shriver Center on Poverty Law, Chicago.

In this model, the social consequence of rank membership results in a small number of individuals in the agent groups being overvalued in social settings, and a larger number of people in the target groups being undervalued. These categories are obviously oversimplifications, arbitrary, often demonstratively false or fabricated.

As the authors say, “People don’t fit well into binary, yes-or-no categories. To use one obvious example, racial categories are only social constructs, and many people have ancestors from many places and connections with many ethnic groups. People are not either ‘white’ or ‘people of color;’ we are various and complex.” 6

Even so, membership in these categories does make an extraordinary difference when it comes to access, opportunity, and success in American life. We don’t have control over most of our rank memberships, but we can control our awareness of them and our responses to the act of categorization.

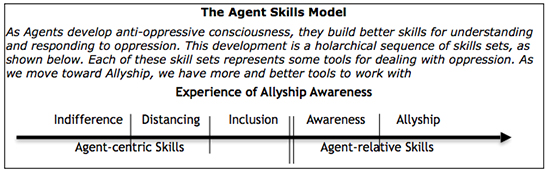

The authors go on to discuss the behavioral skills and mindsets attendant to given rank memberships, those unique to agent and target members. There are also different developmental opportunities to utilize, grow, and activate social change for individuals in different relative social positions. The possible development of agent skills is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The possible development of agent skills in response to oppression.7 Used with permission from the Shriver Center on Poverty Law, Chicago.

As someone who falls almost entirely into overvalued categories, characterized by unearned advantage and benefits at the expense of disadvantaging and restricting access to others with different rank memberships, I am continually reminded of my own privilege by this framework.

It should force us all to ask: What individuals and groups are being undervalued in the social settings around us? Or in professional settings? Legal proceedings? And how do the operation of those rank positions perpetuate further inequality?

We must start from a place of acknowledgment. Only then can we better use our positions to move the workings of the law in a more intentional and just direction.

This article was originally published on the State Bar of Wisconsin’s Public Interest Law Section Blog. Visit the State Bar sections or the Public Interest Law Section web pages to learn more about the benefits of section membership.

Endnotes

1 Leticia Nieto, Margot F. Boyer, Liz Goodwin, Garth R. Johnson, and Laurel Collier Smith, Beyond Inclusion, Beyond Empowerment: A Developmental Strategy to Liberate Everyone, Cuetzpalin, 2010.

2 Leticia Nieto and Margot F. Boyer, “Understanding Oppression: Strategies in Addressing Power and Privilege,” Colors NW Magazine March 2006, pp. 30-33.

3 Nieto and Boyer, "Understanding Oppression," March 2006.

4 See Pamela Hayes, “Addressing the Complexities of Culture and Gender in Counseling,” Journal of Counseling and Development, March/April 1996.

5 Nieto and Boyer, "Understanding Oppression," March 2006.

6 Nieto and Boyer, "Understanding Oppression," March 2006.

7 See Nieto and Boyer, “Understanding Oppression: Strategies in Addressing Power and Privilege, Part 3: Skill Sets for Agents,” Colors NW Magazine March 2007, pp. 34-38.