Oct. 8, 2025 – Growing up in Pittsburgh, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM) Assistant Professor Derek Handley “knew what neighborhoods we couldn’t go to.”

The racial covenants that he researches with UWM Professor Anne Bonds provided the legal foundation for exclusion.

“I think when anyone reads” a racial covenant, “first of all, there’s a shock. And I think what’s shocking about it is the matter-of-factness of it,” Handley said. “The legal language sort of makes it OK.”

UWM’s

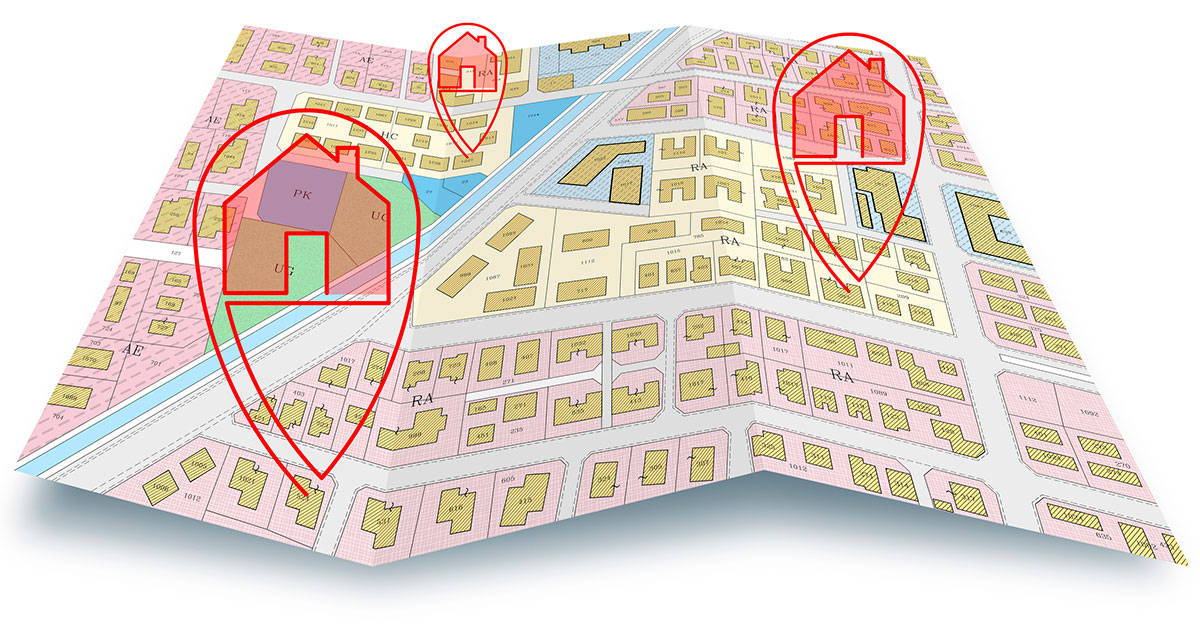

Mapping Racism and Resistance Project, through local volunteers, has allowed Bonds and Handley to map where the covenants appear in Milwaukee County. They expect to present further results Nov. 8 at 1 p.m. at the Milwaukee Central Library.

Their project is one of many across the country, including Dane County, seeking to address this operative part of racial segregation.

The covenants, popular in marketing prestigious residential communities from the 1920s through 1940s across the country, have been unenforceable since 1948.

The hurt of exclusion remains.

Wisconsin has recently addressed the issue by creating a means for an owner to discharge such covenants through recording a standard form.

A Parcel’s Story

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Assistant Professor Derek Handley

The story of a parcel often includes covenants limiting size of houses, density, and cars on the street, down to the type of fences one may build and the color one may paint a home.

In older covenants, a term may appear that “[o]nly members of the Caucasian race shall use or occupy any dwelling on said plat, excepting that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race employed by an owner or tenants.”

Allowing domestic servants, Handley explained, was a means “to establish a social hierarchy.”

Although African American residents were most often restricted, they weren’t the only targeted group. The covenants could be more elaborate and explicitly exclude residents who were Jewish, Irish, or Italian, among others.

The covenants’ popularity arose through population and jurisprudential shifts.

The Great Migration

African Americans seeking better opportunities and more personal freedom than available in Southern states began moving northward starting in 1916. It’s known as the Great Migration.

One response to the influx was to limit where African American citizens could live.

African Americans “escaping the Jim Crow South and coming up north for a better life,” including Handley’s parents, ended up “in a crowded city and urban dwellings, where they were paying more than what it’s worth.

“They are being fed the same American dream that everyone else is being fed when you’re watching the television.”

Northern and Southern cities tried to zone for race. The U.S. Supreme Court held in

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917), that racial zoning violated the anti-discrimination terms of the Fourteenth Amendment at the expense of an owner’s freedom of contract.[1]

Racial covenants sidestepped

Buchanan and received U.S. Supreme Court acceptance in

Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U.S. 323 (1926). The Court considered the covenants mere private contracts.[2]

Using

Corrigan, Wisconsin’s Supreme Court in

Doherty v. Rice, 240 Wis. 389 (1942), allowed equitable relief for property owners to enforce a racial covenant prohibiting African Americans from owning or occupying a parcel in Delavan Lake View Crest Subdivision.

John W. Rice acquired the lakefront property by tax deed, which did not recite the covenant previously included in vesting deeds, and the limitation wasn’t listed on the plat.

Laws of Desegregation

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Professor Anne Bonds

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), departed from

Corrigan’s analysis by concluding that the use of courts for enforcement ensnared government in Fourteenth Amendment unconstitutional discrimination.

Additional cases and legislation strengthened the prohibition.[3]

The

Fair Housing Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. sections 3601-3619, with few exceptions, prohibits refusing to sell or rent, setting discriminatory terms, promoting preferences or discrimination, among other restrictions, on the basis of race, color, or national origin.

Wisconsin provides similar protections in the Open Housing Law, now at Wis. Stat.

section 106.50, which was enacted in

1965 Wis. Act chapter 439, section 4.

The covenants are so old that Wisconsin’s 40-year statute of limitations in Wis. Stat.

section 893.33(6) makes them unenforceable, said Cheri Hipenbecker, general counsel for Knight Barry Title Group in Milwaukee.

Neither

Shelley nor the statutes wiped out the covenants’ racist words. Later transactions continued to use the language, Bonds said, “which I think again speaks to their kind of symbolic meaning.”

The covenant remains of record. A title commitment or policy may reference it as a Schedule B exception, although the commitment or policy will note unenforceability of discriminatory covenants.

Covenants in the Neighborhood

One can expect to find racial covenants in new developments starting in the 1920s and for a few decades afterward.

As Bonds’ and Handley’s research has shown, the covenants appear throughout the state, south to Racine and north to Green Bay. One Walworth County covenant excludes Indigenous people, Bonds said.

Hipenbecker, who as legislative co-chair for the Wisconsin Land Title Association (WLTA) supported legislation to renounce the covenants, remembers a covenant in Door County that she described as “obnoxious.”

Properties in Milwaukee suburbs, as well as those in the city, frequently contained racial covenants. More than 30,000 racial covenants exist in Milwaukee County, Bonds said.

That exceeds the number discovered in University of Minnesota’s

Mapping Prejudice Project in Hennepin County – covering Minneapolis and several populous suburbs – which began before UWM’s Mapping Racism and Resistance Project.

The covenants shaped the “spatial pattern of the city” at initial development, petitions from existing landowners – even for cemetery plots, Bonds said.

“This was done by design, but people are profiting off of this,” Handley explained. “It wasn’t just racism to be blatantly racism. It was money being made off of this system.”

In Dane County, covenants appear mostly in Madison and its suburbs, according to Dane County’s

Prejudice in Places initiative on the county Planning and Development web page, which includes an interactive map.

The covenants cluster in neighborhoods south of Lake Monona, in the Arboretum area, old north-side subdivisions, and in the near west neighborhoods around Midvale Boulevard north to Shorewood Hills.

The map shows only the research done so far, explains Nathan J. Wautier, a real estate attorney with Reinhart Boerner Van Deuren s.c. in Madison. He knows racial covenants encumber Nakoma.

Repudiation on the Record

The governments that once endorsed racial covenants have begun to record their disapproval.

Jay D. Jerde, Mitchell Hamline 2006, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by

email or by phone at (608) 250-6126.

Jay D. Jerde, Mitchell Hamline 2006, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by

email or by phone at (608) 250-6126.

Milwaukee County passed a resolution repudiating racial covenants in 2022. Whitefish Bay, Shorewood, Greendale, Wauwatosa, and the city of Milwaukee passed similar legislation, relying on Mapping Racism and Resistance research, Bonds and Handley said.

Dane County and Madison enacted resolutions earlier this year. Monona enacted its resolution in 2022.

Realtors heard responses to the covenants from buyers, who “were looking at their title commitment and they learned of these discriminatory covenants, and they were pretty taken aback, pretty upset,” said Cori Lamont, Wisconsin Realtors Association (WRA) Vice President of Legal and Public Affairs.

“Some of them were members of a group that would have at one time been prohibited from living in that property, and others were generally just offended.”

The WRA studied what other states were doing and promoted a proposal that received bipartisan support – both sides “wanted to make sure that it wasn’t erasing the language” to “show the history of where we once came from on that property,” Lamont said.

The effort represents WRA’s support for making housing available, including “to address this major gap in the discrepancy between homeownership with those more underrepresented in our state,” Lamont said.

“You never want someone to feel discouraged that they’re looking at this [covenant] thinking, ‘Well, even though you’re telling me it’s not enforceable, it still is impacting me,’ and so we wanted people to be able to have a voice.”

A Standard Form

Cori Lamont, Wisconsin Realtors Association Vice President of Legal and Public Affairs.

2023 Wis. Act 210, enacted March 22, 2024 and codified in part at Wis. Stat.

section 710.25, makes “a discriminatory restriction … void and unenforceable” and prohibits recording a document with one.

Wisconsin’s law places it early among states responding to the issue, said Wautier, who became involved toward the end of the legislation’s development because of his research on the ability to release private restrictions.

As recently as 2017 in

The Color of Law, Richard Rothstein advised that racial covenants “in most states …, though without legal authority, can be difficult to remove from deeds without great expense.”[4]

The state law provides a mechanism for renouncing covenants, including a standard form to list the instruments with restrictive covenants and discharge them from the property.

Dane County Planning and Development refers owners concerned about a discriminatory restriction on their property to visit the WRA’s

website that links up to the

form that can be completed and recorded to renounce the covenant.

Dane County also offers opportunities on its

Prejudice in Places website and at public events to help homeowners discover if their homes are encumbered with the covenants and provide help for the owners to renounce the covenants.

WRA, through its charitable foundation, offers to help cover the cost of recording the document, Lamont said.

History Repeating Itself?

Nathan J. Wautier, a real estate attorney with Reinhart Boerner Van Deuren s.c. in Madison

When Handley’s mom told him stories when he was growing up in the 1980s about hardships from the Great Migration, he thought it was “old timey stuff. … Things are different.”

Now Handley says, “Well, things aren’t different. … The methods have changed. The terminology has changed.”

Wautier sees history repeating itself.

Property owners are “not putting down overt racial restrictions, but they are now getting together and doing the exact same thing with almost exactly the same language of those original plats, limiting the size of the lots, the size of houses, which effectively have a discriminatory impact.”

These new restrictions run “contrary to adopted public policy at the time,” Wautier explained. The City of Madison seeks to encourage increased housing, including multifamily housing and accessory dwelling units.

“So, it’s kind of interesting the overlap,” Wautier said. “I’m sure they wouldn’t say that they are racist, but they will have [an] … impact.”

Endnotes

[1]

See also Richard Rothstein,

The Color of Law 39-57 (2017).

[2]

See also id. at 77-91.

[3]

Id. at 89-91 (explaining subsequent challenges after

Shelley).

[4]

Id. at 91;

see also id. at 221-22 (noting, “The difficulty and expense of eliminating restrictions from deeds varies by state” and providing sample language).