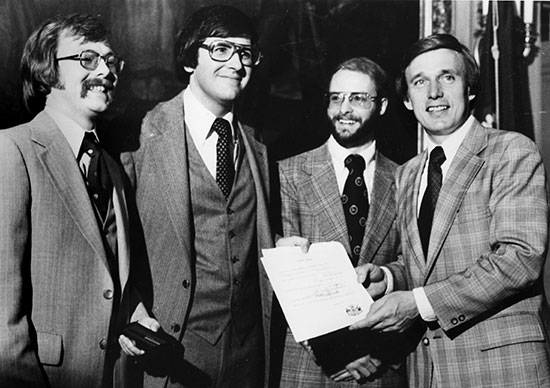

From left: Youth Policy and Law Center Director Rick Phelps; Representative Peter Tropman; Representative Richard Flintrop; and Governor Martin Schreiber pose with the freshly signed Assembly Bill 874, which reformed the treatment of juveniles in corrections. (Photo: Wisconsin Historical Society, Creator: Unknown, Title: Children's Code Supporters, Image ID: 125700. Viewed online at https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM125700.)

June 16, 2021 – Richard J. Phelps compiled some major achievements during his 50-year career. But there’s one accomplishment that set the stage for his entire career: passage of the Children’s Code in 1978, reforming juvenile justice.

“When that bill passed the Assembly after eight years of work, that was the most memorable moment of my career,” said Phelps, a 1971 graduate of U.W. Law School who now celebrates 50 years as a member of the State Bar of Wisconsin.

Phelps’ work on juvenile justice reform in the 1970s proved to be a catalyst for other big initiatives and roles along his 50-year path, including State Public Defender, Dane County Executive, and community leader on revitalization and development at M&I Bank.

“We were about changing the system and winning that fight,” he said. “The stakes were very high for children and families. Once we passed the Children’s Code, I fully expected to win every fight I was ever in. If you want to make real change, you have to believe it can be done.”

In his “retirement,” he is playing a strategic role in helping The Center for Black Excellence and Culture become a reality as a space to teach Black culture, develop Black business and community leaders, and attract Black talent to the Madison area.

This profile highlights the career of Rick Phelps, who used his legal training and natural leadership abilities to make a difference in the state, his community, and beyond.

A Conscientious Objector

Born in Polk County, Phelps was raised in farming communities until his family moved to the south side of Milwaukee, where he attended high school.

He went on to graduate from the U.W.-Madison. Without a clear career direction, a friend encouraged him to take the law school admissions test. He entered law school facing the prospect that he would be drafted for the Vietnam War, which he opposed.

Richard J. Phelps compiled some major achievements during his 50-year career. But there’s one accomplishment that set the stage for his entire career: passage of the Children’s Code in 1978, reforming juvenile justice.

“Everything was being challenged – including our country’s role in the world,” Phelps said. “The civil rights movement was full blown, the women’s movement was exploding.

“There was a huge transformation of awareness, of how justice needs to work for a country to be a great country. I’m not really sure why, but I had always been really affected by notions of what is fair and just.”

Phelps wasn’t going to Vietnam, but he wasn’t going to dodge the draft, either.

“I thought I was going to federal prison. That was my decision,” Phelps said. “They were sentencing people to 18 months for refusing to go. At the same time, I wasn’t interested in going to Canada or giving up my U.S. citizenship. I was going to accept my fate.”

In law school, he filed for “conscientious objector” status, which required him to write an essay on why his beliefs were incompatible with fighting a war. The draft board granted his request, to his surprise, which set the course of his career.

When he obtained the conscientious-objector status, he was assigned to the Dane County Juvenile Defender Program, where he had worked as an intern.

“I did daily detention checks for all the new kids coming into the system,” he said. “I represented many of the kids in trouble in Dane County. Moria Krueger, who later became a judge, started that program and hired me as a staff attorney.”

Reforming Juvenile Justice

In this juvenile defender role, Phelps saw the extent of injustice against children in Wisconsin. In the 1970s, approximately 24,000 kids were incarcerated in adult jails, some in isolation as the only mechanism to separate them from adults.

Some had committed crimes. Others were runaways, truants, or kids with behavior problems. None received the due process necessary to protect their rights.

Very few in the justice system appeared to be looking out for the child’s best interest. Phelps detailed the injustices, and the long road to passage of a new Children’s Code, in an article for Wisconsin Magazine of History.1

“I was interviewing runaways from other counties and they were having completely different experiences with the court system,” said Phelps, noting little accountability and a veil of secrecy that kept many injustices from public view, including strip searches.

“Many of them were in jail or institutions, signed in through contracts and voluntary admissions. We discovered kids institutionalized their entire childhoods who were never given a court hearing. We discovered all sorts of terrible things.”

As young lawyer, Phelps founded and directed the Youth Policy and Law Center, which coordinated legislation on a new Children’s Code. The 120-page legislation took eight years to pass and changed every aspect of the Wisconsin juvenile justice system.

The new Children’s Code included some of the strongest due process protections in the country for juveniles. In addition, implementation of provisions for community-based juvenile delinquency programs (and funding through Youth Aid) slashed child incarceration rates and put many juvenile corrections facilities out of service.

“We started suing people, and not only to drive the legislation,” he said. “We exposed the entire system. Eventually, people were so embarrassed and mortified by it that we got the judges on board with changes to the system.”

Phelps credits Judge Ervin M. Bruner with the courage to listen, and to find alternatives to incarceration for juveniles. “That era really shaped a lot of my views,” Phelps said.

The eight-year battle also gave Phelps momentum and confidence, and when the State Public Defender System faced elimination, Phelps was there to lead the charge.

Restoring SPD

After passage of the Children’s Code, the Youth Policy and Law Center entered Phase 2, implementing the code’s provisions and creating new resources.

Joe Forward, Saint Louis Univ. School of Law 2010, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6161.

Joe Forward, Saint Louis Univ. School of Law 2010, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6161.

“It was time for me to leave,” Phelps said. “I turned it over to a new director and I was hired in the 1980s to salvage the state public defender program, which had been sunsetted out of existence. We had 10 months to keep the program from completely disappearing.”

As the new State Public Defender, Phelps helped lead that charge, starting in 1983. Under support from the Gov. Tony Earl administration, Phelps restored the SPD program, helped eliminate a $3 million structural deficit and won the first rate increase for private bar appointed counsel.

“It became one the best programs in the U.S., and I would argue that it probably still is,” Phelps said. “That happened over the course of five years and when the administration changed, it was time for me to move on. My team did what we set out to do, and we also made significant changes in the diversity of who was running different offices.”

Phelps had brought in Marcus Johnson, a Black attorney, as head of the entire trial division of 27 offices statewide. He also appointed the first woman Deputy State Public Defender, Judy Collins, and various women to head trial offices for the first time in SPD history.

The public defender system intact, Phelps’ phone rang. “I was recruited to run in an eight-person primary for Dane County Executive,” Phillips said. I had no intentions of ever running for office but I ran to change the human services system in Dane County.”

County Executive

At age 41, Phelps won a special election in 1988, and the next year, won a four-year term. “We integrated mental health and social service programs,” he said.

“We decentralized the provision of services to a neighborhood level through a program called Joining Forces for Families, which operates to this day as probably the lead service vehicle for the county.”

Phelps went on to win a second four-year term and took on urban sprawl and environmental issues. “We created an environmental agenda from scratch and focused on eliminating sprawling developments to keep villages and cities healthy,” he said.

“People thought it was very risky because it was controversial,” Phelps said. “But I knew that the Dane County people would respond to stop the sprawl that was ruining the countryside, something that is unique to Dane County. They did in force.”

And when his second term was up in 1987, Phelps called it quits, but not before becoming president of a national association for county executives, representing the interests of the national organization at the White House and Congress.

The polling showed a probable third term as Dane County executive. “But when you are strong and you feel like you’ve done what you said you were going to do, then you run to maintain what you’ve done,” Phelps said. “I wasn’t interested in that. For me, it’s all about change.”

Fourth Act

After he left office, Bob Schlicht, then president of M&I Bank in Madison, convinced Phelps to be a senior vice president at the bank, do community outreach and keep tabs on the community pulse, no strings attached.

“He kept his word,” Phelps said. “That gave me the freedom to work on development projects and do other things I wanted to do.”

In 2009, Phelps headed former Chief Justice Shirley Abrahamson’s finance committee for a fourth term on the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

“She called me one night and had $60 in the bank,” Phelps said. “Our fundraising campaign set a fundraising record at the time.”

Phelps is also an adventurer. He and his wife moved to New York City in the early 2000s. They had a view of the Twin Towers before 9/11 happened.

“We were traveling, and when we came back, what had filled our living room window were just spirals of smoke,” he said. “It was just unbelievably devastating.”

Shortly after, the Partnership for New York City – a group of prominent business leaders and CEOs – recruited Phelps to lead its government relations team, to help reorganize the local, state, and federal effort to bring New York City back economically.

After reorganizing the group’s federal lobbying efforts Phelps returned home to Madison, leading a charge to develop a major area that stood vacant and underutilized.

“We needed to grow a neighborhood, not just startups,” Phelps said. “We needed people to live there, to attract and keep talent in Madison.” Today, the East Corridor is booming, with a central grocery store, small business, and neighborhood feel.

“Retirement”

Now, in “retirement,” Phelps is using his talents and experience to help Rev. Dr. Alex Gee, founder of the Center for Black Excellence and Culture on Madison’s south side.

“This is a transformational place focused on the excellence in Black culture, a project conceived and defined in the Black community and now backed by a major civic coalition,” he said. “This will be a tremendous asset for the community.”

Phelps said in every job he ever had, or any project he worked on, the central theme was always making things better for people and the community. “That continues to this day, but it really started back in the 1960s, in law school.”

Phelps said he is seeing, today, similar elements of the societal and cultural empowerment that fueled change when he began his career 50 years ago.

“I think some empowerment has come back,” he said. “For a while, it was completely gone, where young people felt, ‘this is too big for me. I can’t change this.’”

“Now, you’ve got movements that are actually having an impact, such as Black Lives Matter. That sense of empowerment that was there in the 1960s is now back in this culture. I think that’s really important for the trajectory of the country.”

Endnotes

1 Richard J. Phelps, “The Children’s Code: Securing Due Process for the Children and Families in Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Magazine of History (Winter 2016-17)