On April 17, 2009, the Obama EPA Administration took the first step in creating a comprehensive regulatory program aimed at climate change by releasing a proposed finding that greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere endanger public health and welfare (the Endangerment Finding).1 The EPA also proposed finding that GHG emissions from new motor vehicles are contributing to these atmospheric GHG levels (the Contribution Finding).

On April 17, 2009, the Obama EPA Administration took the first step in creating a comprehensive regulatory program aimed at climate change by releasing a proposed finding that greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere endanger public health and welfare (the Endangerment Finding).1 The EPA also proposed finding that GHG emissions from new motor vehicles are contributing to these atmospheric GHG levels (the Contribution Finding).

This proposal represents a historic shift in environmental regulatory policy for the United States and could ultimately trigger a cascade of wide-reaching federal Clean Air Act (CAA) regulations that could affect nearly every aspect of our economy. The magnitude of this action was expressed by U.S. Rep. Edward J. Markey (D-MA):

History will judge this action by EPA … as the environmental equivalent of what Brown v. Board of Education meant to our nation’s civil rights laws. Just as that decision sparked a generation to alter our very way of daily life, so will the [EPA’s Endangerment Finding] be considered by future generations as pushing our nation into a new clean energy direction.

Background on the Endangerment Finding

The EPA’s proposal responds to a 2007 U.S. Supreme Court decision interpreting section 202 of the CAA, which regulates air emissions from motor vehicles.2 The Court held that carbon dioxide – itself a GHG – is an “air pollutant” for purposes of the CAA. The Court further directed the EPA to determine whether CO2 from motor vehicles “causes, or contributes to, air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.”3 A positive Endangerment Finding and Contribution Finding under section 202 would require that EPA develop regulations to control CO2 and other GHGs from motor vehicles.4

In July 2008, the Bush EPA Administration published an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR) outlining how GHG might be regulated under the CAA and soliciting comments on how the EPA should address the Supreme Court’s directives.5 Then-EPA Administrator, Stephen L. Johnson, concluded that the CAA was ill-suited to regulate GHG emissions because of the ubiquitous nature of CO2, as well as the significant bureaucratic burdens and costs associated with doing so. In a nutshell, the Bush EPA “punted” on the issue, leaving the decision to the next administration.

The EPA’s Proposed Endangerment and Contribution Findings

The EPA’s April 17, 2009 proposal has two parts. The proposed Endangerment Finding concludes that GHG emissions in the atmosphere – as a class of pollutants – are reasonably anticipated to endanger the public health and welfare of current and future generations. The Contribution Finding concludes that GHG emissions from new motor vehicles “cause or contribute” to these air pollution levels.

The most immediate and direct effect of these findings, if finalized, would be the regulation of GHG emissions from new motor vehicles. On this point the EPA explicitly states that its proposal is limited to mobile sources and would not itself impose any new requirements on industry or other entities.6 These motor vehicle regulations would be promulgated through separate rulemakings to be initiated after finalizing the Contribution Finding.

Despite the explicit limitation to motor vehicles, the proposed Endangerment Finding is widely seen as setting the groundwork for future EPA-imposed regulations on industrial and other GHG sources. For example, the proposed Endangerment Finding addresses six GHG pollutants – carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons and sulfur hexafluoride. Yet only four of these pollutants are released from motor vehicle tailpipes, suggesting that the Endangerment Finding will be used to trigger CAA regulations on stationary emission sources, not just motor vehicles.

The EPA has set a 60-day public comment period that will end June 23, 2009.7 Public hearings will be held on May 18 and May 21, 2009 in Arlington, Va., and Seattle, Wash., respectively.8

Potential Impact of the Endangerment Finding

The EPA’s proposed findings could lead to wide-reaching regulatory requirements on many sectors of society.

As mentioned, the proposed Contribution Finding will almost certainly result in regulation of GHG emissions from automobiles. There is no available control technology for CO2, so mobile-source emission standards will likely require automakers to produce more hybrid and electric-powered vehicles. Environmental groups have also announced plans to push the EPA to expand its Contribution Finding to encompass other mobile sources of emissions, such as airplanes and off-road vehicles.9

The larger concern being expressed by industry and the private sector is that the Endangerment Finding will be used to regulate GHG emissions from stationary sources under the existing CAA. Of particular concern is the possibility of regulating CO2 emissions, a ubiquitous pollutant emitted from all combustion sources (boilers, heaters, furnaces, etc.), under the entire CAA. CO2 is frequently emitted by stationary sources at rates that are an order of magnitude above the regulatory triggers for existing CAA regulatory programs. Accordingly, well over one million new sources that are currently exempt from CAA regulation could be pulled into this extremely complicated program.

A study by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, using information from the U.S. Census Bureau and Energy Information Administration, concluded that regulating CO2 under the CAA would subject more than one million new commercial-sector sources to the CAA air permitting program.10 This would expand the program to nonindustrial facilities such as schools, restaurants, churches, hotels, and office buildings. Approximately 200,000 additional industrial manufacturing sources also would be subjected to the program, along with 17,000 agricultural sources.11 Private-sector commenters have stated that expanding the CAA permitting program to cover a much broader section of the economy would add bureaucratic delay and expense that will hobble an already fragile economy.12

Proponents of using the CAA to regulate GHGs assert that the U.S. Chamber of Commerce report is a “scare tactic,” and that the EPA would not impose permitting requirements on such “smaller sources.” They argue that although the CAA regulatory thresholds are defined within the CAA, the EPA has authority to use different regulatory thresholds without Congressional action.13

Some environmental groups, such as the Sierra Club, are not waiting for a final Endangerment Finding, but are prosecuting lawsuits throughout the country, including Wisconsin, arguing that the CAA already regulates CO2 emissions.14 These claims have found little success in the courts; they have been rejected by the Bush EPA15 and preliminarily rejected by the Obama EPA.16 Nonetheless, this type of litigation will likely be emboldened by the proposed Endangerment Finding.

Pressure for Congressional Action?

The Obama Administration has signaled that the CAA would be a poor mechanism for regulating GHG and has publicly expressed a desire that Congress enact separate legislation to address climate change.17 This reflects a belief that sweeping regulatory programs with the potential for such profound societal impacts should be crafted by elected officials, not unelected regulatory agencies.

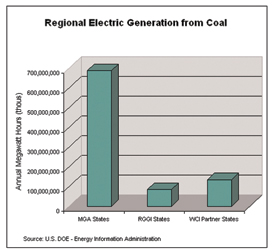

To date, however, comprehensive global-warming legislation has not gained enough support for passage in Congress, largely due to the current economic climate and the potential for profound negative impacts on the economy, particularly in the Midwest.18 Legislation may take the form of a cap-and-trade program that would require emitters of CO2 and other GHGs to buy emission permits. The hardest hit sector of the economy would be electric power producers that burn coal, who would simply pass these costs of these GHG permits on to their customers. By far, the Midwest economy would be the hardest hit by such a program because it is so much more reliant on coal-fired electric generation than the east and west coasts. See Table 1.

To date, however, comprehensive global-warming legislation has not gained enough support for passage in Congress, largely due to the current economic climate and the potential for profound negative impacts on the economy, particularly in the Midwest.18 Legislation may take the form of a cap-and-trade program that would require emitters of CO2 and other GHGs to buy emission permits. The hardest hit sector of the economy would be electric power producers that burn coal, who would simply pass these costs of these GHG permits on to their customers. By far, the Midwest economy would be the hardest hit by such a program because it is so much more reliant on coal-fired electric generation than the east and west coasts. See Table 1.

Table 1. Regional electric generation from coal comparing the Midwest states, East Coast RGGI states and West Coast WCI states.

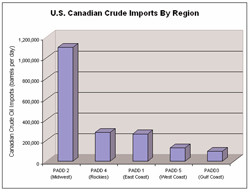

There is concern that the Midwestern transportation-fuel supply also could be disproportionately burdened by federal cap-and-trade legislation. Such a program would discourage the use of crude oil derived from Canadian oil sands, a crude type that is used more in the Midwest than elsewhere in the country. See Table 2.

Table 2. Regional use of Canadian crude.

Table 2. Regional use of Canadian crude.

Where to Learn More on the Impacts of CO2 Regulation Under the CAA?

It is quite possible that EPA, or court action, will soon subject many of your business clients to CAA requirements for the first time. Whether they will face air permitting requirements or compliance with air emission standards, your clients could be thrown into a program that is regarded as one of the most complex and bureaucratic of all federal regulations. They will need legal help.

A good overview of these CAA requirements, with practical advice for compliance, is contained in Volume 2, The Wisconsin Business Advisor Series: Environmental and Real Estate Law (State Bar of Wis. CLE Books, 2006 & Supp.). This book contains an entire section on CAA obligations that are imposed on businesses in Wisconsin. Additional information related to the EPA’s proposed findings can be found on the EPA’s Web site, which should be checked periodically.19

Endnotes

174 Fed. Reg. 18,886 (April 24, 2009) available at http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2009/pdf/E9-9339.pdf.

2Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. 497 (2007).

3Id. at 533.

4Although the Court directed the EPA to make an endangerment finding under section 202 (pertaining to mobile sources), virtually identical endangerment language appears elsewhere in the CAA for other types of emission sources. See, e.g., 42 U.S.C. §§ 7408(a) (air Quality Criteria must be created for pollutants that “cause or contribute to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.”); 7411(b) (New Source Performance Standards must be created for sources that “cause, or contribute significantly to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.”); 7412(b)(National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants are required for pollutants that “present, or may present, …a threat of adverse human effects…or adverse environmental effects.”); 7415(a)(International air pollution); 7545(c)(Regulation of Fuels); 7547(a)(Non-road engines and vehicles emissions); 7571(a)(Aircraft emissions); 7671n (Substances affecting the stratosphere). Accordingly, it is widely believed that a positive GHG Endangerment Finding under section 202 will ultimately require the EPA to issue positive endangerment findings under other sections of the CAA as well. Environmental groups have already filed petitions with EPA seeking similar endangerment/contribution findings under several other sections of the CAA. This would trigger a wide variety of GHG regulatory requirements for many types of air-emissions sources, including power plants, boilers, and agricultural facilities.

573 Fed. Reg. 44,354 (July 30, 2008).

674 Fed. Reg. 18.909 (Apr. 24, 2009).

774 Fed. Reg. 18,886 (Apr. 24, 2009).

8Id.

9See 42 U.S.C. §§ 7547(a)(non-road engines and vehicles emissions) 7571(a)(aircraft emissions).

10U.S. Chamber of Commerce, A Regulatory Burden: The Compliance Dimension of regulating CO2 as a Pollutant (Sept. 2008), available at http://www.uschamber.com/assets/env/regulatory_burden0809.pdf.

11To put this in perspective, a February 2004 report from the Wisconsin Legislative Audit Bureau concluded that Wisconsin issues, on average, only 16 CAA permits per year. Id. Further, preparation of the application for a permit often requires the use of an outside consultant, and the applications frequently take more than one year to issue.

12http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/23/AR2009032301068.html.

1373 Fed. Reg. at 44,503 (July 30, 2008) citing Nixon v. Missouri Municipal League, 541 U.S. 125 (2004); United States v. American Trucking Ass’n, Inc. 310 U.S. 534 (1940); Rector of Holy Trinity Church v. U.S., 143 U.S. 457 (1892).

14See, e.g., In re Deseret Power Elec. Coop., PSD Appeal No. 07-03 (E.A.B. Nov. 13, 2008); Sierra Club v. Menasha Utils., et al., Case No. 1:09-CV-00122-WCG (E.D. Wis.) (Complaint filed February 6, 2009). But see Sierra Club, et al. v. Wisconsin Public Serv. Comm’n, Case No. 06-CV-1204 (Dane County) (Asserting that “greenhouse gases are not currently regulated by Illinois or the United States.”).

1573 Fed. Reg. 80,300 (Dec. 31, 2008) - (Memorandum dated December 18, 2008 from former EPA Administrator Stephen L. Johnson, entitled “EPA’s Interpretation of Regulations that Determine Pollutants Covered by Federal Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) Permit Program.”) available at http://www.epa.gov/NSR/documents/psd_interpretive_memo_12.18.08.pdf.

1674 Fed. Reg. 18,905, fn. 29 (Apr. 24, 2009).

17Press release of EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson dated April 17, 2009 (“…both President Obama and Administrator Jackson have repeatedly indicated their preference for comprehensive legislation to address this issue and create the framework for a clean energy economy.”), available at http://yosemite.epa.gov/opa/admpress.nsf/0/0EF7DF675805295D8525759B00566924 .

18Cap and Burn, Wall Street Journal, June 9, 2008 (“After the bill bottomed out, no fewer than 10 Democrats from the Midwest and South—whose economies rely on coal-fired power or heavy industry and thus will be disproportionately affected—registered their displeasure with Mr. Reid and Ms. Boxer. Including Sherrod Brown (Ohio), Carl Levin (Michigan), Jay Rockefeller (West Virginia) and Jim Webb (Virginia), the Senators said they could not support cap and trade ‘in its current form’ because it would cause ‘undue hardship on our states, key industrial sectors and consumers.’”), available at http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121296724450055721.html?mod=googlenews_wsj.

19http://epa.gov/climatechange/endangerment.html.

Todd E. Palmer, St. Louis Univ. 1992, is a shareholder with DeWitt Ross & Stevens, Madison, and practices in environmental, administrative, and patent law. He is admitted to practice in Wisconsin and Illinois and is a registered patent attorney.

• Post a comment