March 16, 2022 – Panelists at the State Bar of Wisconsin’s Equal Justice Conference on March 10 surveyed a range of access to justice issues. For the first time, the conference was held virtually.

“Your Volunteers Can Be From Anywhere’

During the morning plenary session, “Pandemic Challenges and Opportunities in Legal Aid,” panelists discussed changes to service delivery models forced by the pandemic.

Jeff M. Brown is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6126.

Jeff M. Brown is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6126.

The switch to virtual appointments made things more convenient for clients.

Clients could meet with lawyers without spending bus fare or gas money, and without having to arrange for childcare or take time off work. They also didn’t have to spend hours in a crowded waiting room.

But the switch meant more work for service agencies. In addition to their other duties, staff had to manage an electronic appointments system – including sending reminders and Zoom links and teaching clients how to use Zoom.

“I do think the advantage of having an appointment-based service is probably better for the people we’re seeing but harder for us to manage internally,” said Angela Schultz, assistant dean for public service at Marquette Law School.

On the other hand, the move to virtual appointments meant access to more volunteers.

“When you run virtual clinics, your volunteers can be from anywhere,” said Jill Kastner, a lawyer with Legal Action of Wisconsin and former president of the State Bar.

‘It’s Been Heartbreaking’

Virtual court hearings and clinics are all well and good for those with reliable internet access. But many people in rural Wisconsin lack such access, said Michele Statz, an anthropologist of law and assistant professor at the University of Minnesota Medical School.

“It’s been heartbreaking to see how many individuals have to attend court in their car, parked outside of a library where they can access the internet, and this in the dead of winter,” Statz said.

Statz said that those working to improve access to justice should do more than just rely on technology.

“These technical innovations are exciting and intuitive and important,” Statz said. “I just don’t know that they’re keeping all of those factors in mind.”

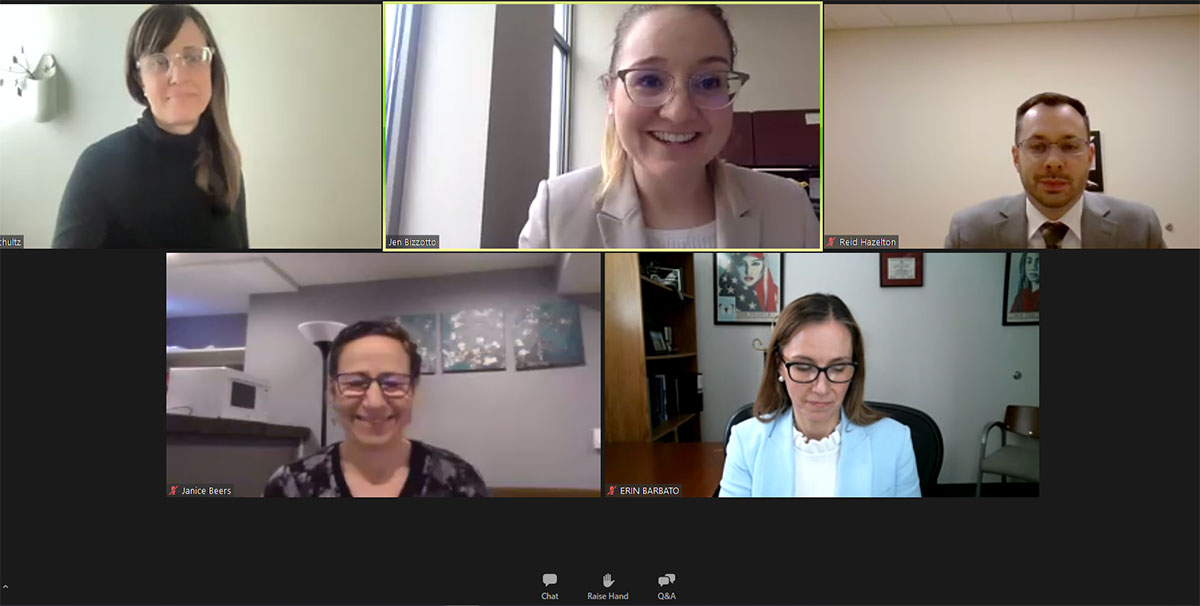

Clockwise from upper left: Angela Schultz, Jen Bizzotto, Reid Hazelton, Erin Barbato, and Janice Beers discussed efforts to help Afghan refugees at Fort McCoy last autumn.

Rise in Demand for Eviction Help

During a morning breakout session titled “Eviction Prevention and Defense in Wisconsin,” panelists detailed how the pandemic increased stressors on both rural and urban renters.

Amy Koltz, executive director for Mediate Wisconsin, said the Milwaukee-based nonprofit saw the demand for its services jump by 107% from 2019 to 2020, and by another 45% from 2020 to 2021.

Koltz attributed the rise in demand to the decrease in housing stock and an increase in the number of out-of-state corporate landlords, who often raise rents and are less willing to work with local agencies to resolve rent disputes.

She said that a boost in rental assistance, part of the congressional pandemic relief package, also played a role in the rises in demand.

Karen Bauer, a lawyer with the Legal Aid Society of Milwaukee, emphasized how overwhelming an eviction can be.

“Without a roof over your head, all the other things in your life are going to be very, very difficult,” Bauer said.

Clockwise from upper left: Monica Cail, Jennifer Johnson, Michelle Brandemuehl, and Dr. Emma Shakeshaft discussed racial justice efforts.

‘It Was Crumpled, It Was Wrinkled, It was Bloodstained’

Panelists during the afternoon plenary session “Legal Efforts to Assist With Afghan Resettlement in Wisconsin” discussed efforts by volunteers at Fort McCoy in the wake of the United States’ pullout from Afghanistan last fall.

Sahar Taman, a lawyer with Fort McCoy Legal Clinic, said volunteers waded through myriad immigration forms to determine how to best help refugees legally settle in the United States of America.

“We did lots of presentations [for refugees] but really, for the first six weeks nobody knew what was next in terms of immigration,” Taman said.

One of the volunteers, Reid Hazelton, a 3L at Marquette Law School, described undergoing a “crash course in immigration law” upon his arrival at Fort McCoy.

The first refugees he helped were two brothers. Hazelton worked to document the harm the brothers would face if they returned to Afghanistan. A showing of harm is key to any successful application for asylum, Hazelton said.

In response to Hazelton’s questioning, one the brothers produced paperwork that he’d hidden in his shoe.

“When they handed that to us, it became real,” Hazelton said. “It was crumpled, it was wrinkled, it was bloodstained. They said they had to hide it in their shoe, to get it past a Taliban checkpoint.”

Clockwise from upper left: Judge Gwendolyn Topping, Katie Chu, Dr. Michele Statz, and Rebecca Rapp discussed longstanding barriers to access to justice for rural populations.

Racial Inequities Transcend Law

In a morning breakout session titled “Pursuing Racial Justice and Racial Equity in Legal Aid,” panelists discussed their efforts to advance racial justice in their practices.

Monica Cail, a lawyer with Legal Action of Wisconsin, said racial justice work often bumps up against hidebound notions of a post-racial society.

“There this idea of a color-blind approach to things, but if folks are starting out from different places initially … Those inequities still persist. Getting that to click has proven really difficult.”

Jennifer Johnson, Director of Diversity and Inclusion with Legal Aid of Wisconsin, said that diversity professionals often must prove the value of their work to legal organizations, where the main focus is on client service.

That focus proceeds upon a false dichotomy, Johnson said.

“If we make ourselves better, we’ll be better lawyers.”

Dr. Emma Shakeshaft, a staff lawyer at ACLU Wisconsin, said solving racial justice issues will require work in all sectors of society.

“Many of these things are problems that courts alone can’t solve, so I view my work as just one tool that can be used to dismantle and combat racial inequality. But a lot of them transcend legal frameworks – intentionally so – because they’re deeply entrenched in our society.”

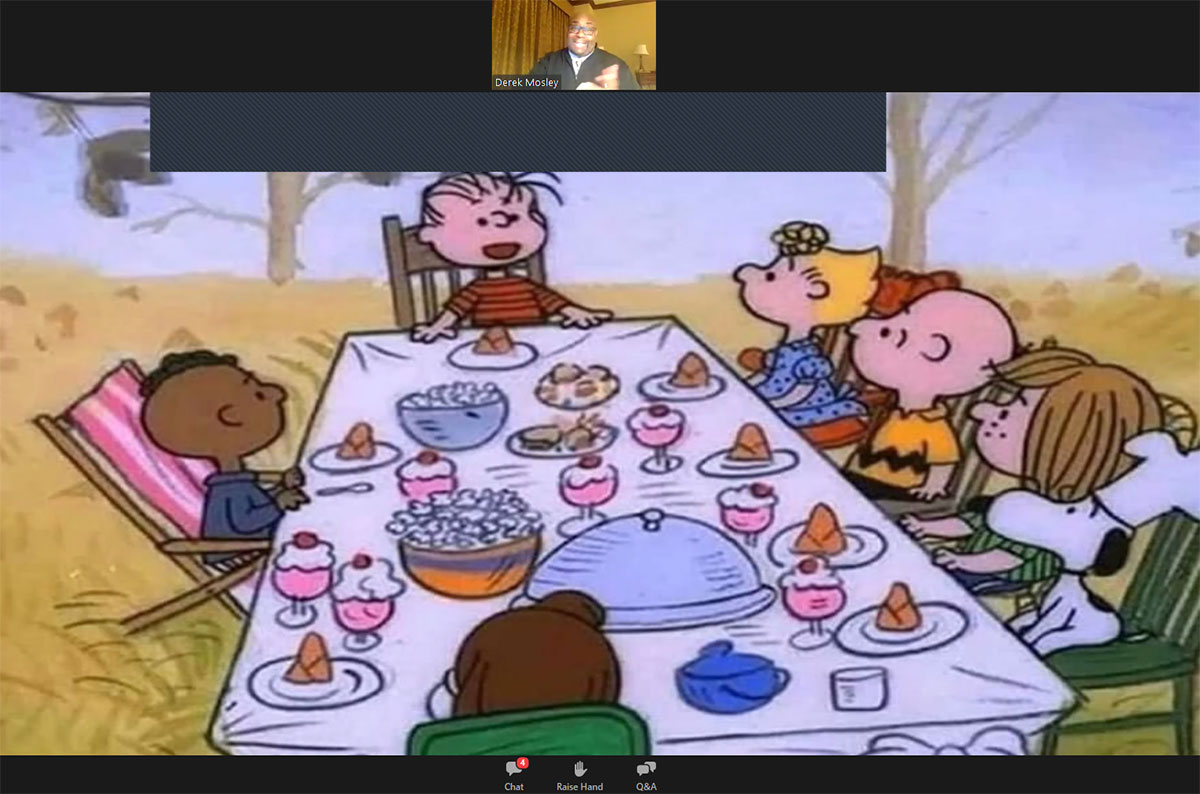

A still shot from the 1968 Charlie Brown Thanksgiving Special, which Judge Derek Mosley cited as an example of unconscious racial bias.

‘You Never Had a Chance’

Judge Derek Mosley, a City of Milwaukee Municipal Court Judge, presented the closing plenary session, which was titled “Unconscious Bias: Knowing What You Don’t Know.”

Mosley defined unconscious bias as a 1) bias for or against a group of people that 2) is subconscious and 3) runs contrary to the holder’s stated beliefs and attitudes.

Researchers at Harvard University have created an implicit association test to measure unconscious racial bias. Mosley said that 83% of white people and 70% of Black people who have taken the test hold an unconscious anti-Black bias.

According to Mosley, that 70% of Black people hold such a bias shouldn’t be surprising, considering the onslaught of anti-Black messages that permeate popular culture.

“From the time you were small to the age you are now, you’ve been bombarded with information like this,” Mosley said. “You didn’t stand a chance.”

Mosley cited as an example the ugly duckling fairy tale.

In that tale, a black cygnet is raised with a clutch of yellow ducklings, who mock him for his coloring. When the cygnet grows into a gleaming white swan, “all those other ducks come back and say to him, ‘Oh my god, you’re so pretty.’ Think of the images.”

Mosley said he had to endure learning that fairy tale as the only Black child in his elementary school class.

“You look around and say [to yourself] ‘I’m the ugly duckling.’”

Another example is the Charlie Brown Thanksgiving Special, an animated TV show written by “Peanuts” creator Charles Schulz.

Schultz fought for permission to include a Black character in the show before it aired in 1968. CBS, the network airing the show, agreed to Schultz’s demand.

But then, having created a Black character, Schultz seated him all alone on one side of the Thanksgiving table, opposite the white characters.

“The point of this all is to make sure that we understand and are aware of the fact that we may have unconscious bias,” Mosley said. “It’s going to take internal motivation and habitual practice to mitigate those facts.”