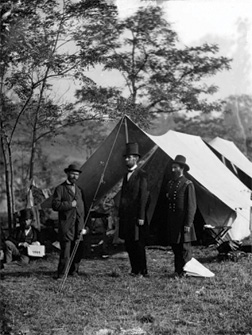

Major Allen Pinkerton, President Lincoln, and General John McClernand at Antietam, Oct. 3, 1862. Photo by Alexander Gardner. On the left-hand side the man holding a sign marked “7479” was one of Gardner’s assistants helping to identify the photo after it was developed.

It is a truism that the rule of law is put to its most severe test in wartime. For centuries this principle has been embedded in the Latin saying inter arma silent leges (in time of war, the law is silent). When a nation feels its very existence to be threatened, laws – sometimes even basic freedoms – that are believed to pose an obstacle to survival often are summarily overridden.

How to win a war without destroying the freedoms the war is being fought to protect is a problem that has bedeviled the United States throughout its history. Abraham Lincoln had to deal with the Civil War, America’s most agonizing war, and with equally difficult civil liberties dilemmas that the war raised. Lincoln brought freedom to millions of slaves and was the most eloquent advocate of the “new birth of freedom” the war ultimately conferred on all Americans, but he also systematically overrode civil liberties in an effort to check fierce opposition in the North that he believed imperiled the Union war effort. Lincoln’s actions led to public debate and a series of court decisions, including a crucial Wisconsin Supreme Court decision, that did much to shape early American civil liberties law. The debate over the proper balance between national security and civil liberties continued during World War I, when Wisconsin again made important contributions to the continuing evolution of free speech law.

Lincoln, Wisconsin, and Civil Liberties During the Civil War

During the Civil War, Wisconsin contributed actively to two key debates over civil liberties: whether President Lincoln had the right to suspend habeas corpus and summarily arrest civilians in loyal states, and whether the military draft authorized by Congress and implemented by Lincoln in 1862 was constitutional.

In early 1861, northern antiwar sentiment nearly destroyed the Union war effort in its infancy. Maryland and other border states were on the brink of secession. If Maryland left the Union, the capital at Washington would be surrounded by the Confederacy and effective direction of the war effort would be nearly impossible. With Lincoln’s blessing, Union military officials suspended habeas and arrested many Marylanders who were suspected of actively aiding the Confederacy.1 One such prisoner, John Merryman of Baltimore, secured a writ of habeas corpus from Chief Justice Roger Taney in the summer of 1861. (In the 1860s, federal law required U.S. Supreme Court justices to perform double duty as circuit judges, and Taney granted the writ while sitting as a circuit judge in Maryland.) After Union officials ignored the writ and refused to release

Merryman, Taney issued a blistering opinion charging that Lincoln had usurped powers belonging

to Congress. Relying heavily on Article I, § 8 of the U.S. Constitution (which enumerates Congressional powers and prohibits the suspension of habeas corpus “unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it”), Taney issued an opinion declaring that only Congress, not the president, was empowered to suspend habeas.2

Learn More

Abraham Lincoln’s Legacy to Wisconsin Law

Lincoln arguably has done more than any other individual to shape America. He influenced and was influenced by powerful legal and political currents that continue to play a vital role in shaping American law, including the law of Wisconsin.

“Abraham Lincoln’s Legacy to Wisconsin Law, Part 1: A New Birth of Freedom – Civil Rights law in Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Lawyer, December 2008

“Abraham Lincoln’s Legacy to Wisconsin Law, Part 2: Inter Arma Silent Leges: Wisconsin Law in Wartime,” Wisconsin Lawyer, February 2009

“Abraham Lincoln’s Legacy to Wisconsin Law, Part 3: The Free Labor Doctrine,” Wisconsin Lawyer, April 2009

Lincoln ignored Taney’s decision. In a subsequent message to Congress Lincoln tacitly acknowledged that Congress, not the president, had primary power over habeas but he made a powerful appeal to the laws of necessity and interpreted his presidential oath (which also is prescribed by the Constitution) to require him to preserve the government at all costs. “[A]re all the laws, but one, to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces, lest that one be violated?” Lincoln asked. “Even in such a case, would not the official oath [to support the Constitution] be broken, if the government should be overthrown, when it was believed that disregarding the single law, would tend to preserve it?”3

Opposition to the Union war effort was not limited to the Confederacy. Many Wisconsin “peace Democrats,” including Edward Ryan, a leading lawyer and politician who eventually became the state’s chief justice, flirted with active resistance to the war effort. In late 1862, efforts to implement the military draft sparked riots throughout Wisconsin. In Port Washington the draft commissioner “was assaulted, stoned, badly bruised and beaten, and compelled to run for his life,” after which rioters destroyed his house and much of the city’s business district.4State troops arrested the riot’s leaders, who then retained Ryan to challenge their detention.

Ryan made arguments similar to those Taney had made in Merryman. In In re Kemp (1863), the Wisconsin Supreme Court agreed that Taney’s reasoning was “unanswerable” and Lincoln’s suspension of habeas was unconstitutional and ordered that the riot’s leaders be released from detention.5 The Wisconsin justices acted much more reluctantly than had Taney. Chief Justice Luther S. Dixon went out of his way to note that Lincoln had “acted from the highest motives of patriotism,” and the Wisconsin court decided to refrain from enforcing the writ until appeal proceedings before the U.S. Supreme Court were completed. At about the same time, the Wisconsin court rejected a separate challenge Ryan had mounted against the draft itself. The court held that the U.S. Constitution clearly gave Congress power to implement a draft for purposes of national defense and that Congress had not improperly delegated power over the draft to Lincoln: It had allowed him only to implement, not to set, draft policy.6

The Kemp decision attracted national attention and caused Lincoln great concern because it presented the first opportunity for full U.S. Supreme Court consideration of whether the Constitution authorized the president to suspend habeas or limited that power to Congress. Fortunately, soon after Kemp was decided, Congress formally authorized Lincoln to suspend habeas, and the Wisconsin Supreme Court later concluded that Congress’s action mooted the issue.7

The U.S. Supreme Court wrestled with other war-related civil liberties issues both before and after the Confederacy’s final defeat at Appomattox. During the war the North was divided into military districts for administrative purposes, and commanding generals occasionally arrested active opponents of the war and had them tried by military courts. After Congressman Clement Vallandigham of Ohio charged Lincoln with waging war “for the purpose of crushing out liberty and erecting a despotism” and “restrain[ing] the people of their liberties,” General Ambrose Burnside arrested him for “disloyal practice[s] affording aid and comfort to Rebels.” The arrest triggered a substantial outcry from Lincoln’s opponents and supporters alike.8

Lincoln, though privately irritated with Burnside, defended the arrest on the ground that Vallandigham’s speech posed a direct threat to military recruitment. Lincoln conceded that the arrest would have been unlawful if Vallandigham had limited himself to political criticism, but Lincoln defended the arrest because he believed that Vallandigham “was laboring, with some effect, to prevent raising of troops [and] to encourage desertions from the army.” “Must I shoot a simple-minded soldier boy who deserts,” Lincoln asked, “while I must not touch a hair of a wily agitator who induced him to desert?”9

Joseph A. Ranney, Yale 1978, is a trial lawyer with DeWitt Ross & Stevens S.C., Madison and Brookfield. He is the author of Trusting Nothing to Providence: A History of Wisconsin’s Legal System (1999) and In the Wake of Slavery: Civil War, Civil Rights and the Reconstruction of Southern Law (2006). He also is an adjunct professor at Marquette University Law School and a member of the Wisconsin Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission.

Joseph A. Ranney, Yale 1978, is a trial lawyer with DeWitt Ross & Stevens S.C., Madison and Brookfield. He is the author of Trusting Nothing to Providence: A History of Wisconsin’s Legal System (1999) and In the Wake of Slavery: Civil War, Civil Rights and the Reconstruction of Southern Law (2006). He also is an adjunct professor at Marquette University Law School and a member of the Wisconsin Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission.

In fact, Vallandigham had confined himself to general criticism of the war and of Lincoln and had not urged his audience to disobey the law. Ultimately, Lincoln freed Vallandigham on condition that he go South, and Lincoln also made clear to the arresting officials that speech should be more broadly protected.10 Vallandigham challenged the military’s power to arrest and try civilians for criticism of the war and his case ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court, but in In re Vallandigham (1864), the Court finessed his challenge by holding that it did not have jurisdiction over military courts.11

Shortly after the war, the issue of the military’s power over civilians arose again, and this time the Court did not avoid it. In Ex parte Milligan (1866), which involved the arrest of an Indiana civilian who had actively tried to sabotage the war effort, the Court held that civilians could not be tried by military courts as long as civilian courts were functioning and martial law had not been declared. Justice David Davis, a Lincoln appointee to the Court who wrote the majority opinion, sternly emphasized that the Constitution “does not say, after a writ of habeas corpus is denied a citizen, that he shall be tried otherwise than by the course of the common law.”12

Wisconsin contributed indirectly to the debate over the proper line between military and civilian authority through the case of In re Tarble (1870).13 Tarble, who was under the minimum age for enlistment, joined the army after the war; his father then obtained a writ of habeas from a state commissioner ordering federal authorities to release the boy. The Wisconsin Supreme Court, still somewhat wedded to the states’ rights doctrine it had espoused in the Booth cases (discussed in a previous article in this series),14 held that state courts had power to issue writs of habeas against federal officials. Chief Justice Dixon, dissenting, pointed out that Taney had held in Booth that only federal courts could issue such writs. On appeal the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with Dixon and summarily reversed the Wisconsin court. Tarble definitively established that state courts cannot issue or enforce writs of habeas corpus against federal officials.15

World War I: Suppressing Dissent in Wisconsin

The issue of permissible wartime restrictions on speech was not fully addressed during the Civil War, due largely to the fact that except for the Vallandigham case Lincoln’s administration made few attempts to suppress speech.16 A full debate did not occur until World War I, and Wisconsin played a central role in that debate.

Life in the United States between the two wars was marked by ethnic and economic friction between old settlers and new immigrant groups, between people who were comfortable with the new balance of power in an economy increasingly dominated by large industrial companies and organized labor and people who clung to a simpler agrarian ideal. Wisconsin was no exception.17 Americans on both sides of these divides, impelled by “an increasing insistence on the interests of the community and on their protection by the state,” viewed opposing speech as a threat and looked for ways to limit that threat.18 As a result, when the United States entered World War I in 1917, conditions were ripe for restriction of speech in the name of national security.

Congress quickly responded to concerns about disloyalty among Americans of German descent by enacting the Espionage Act of 1917, which made it a crime to mail materials “advocating treason, insurrection, or forcible resistance” to the war effort or to criticize the flag, the armed forces, or the American form of government. Congress also prohibited speech that tended to discourage enlistments or draft registrations, and it required publishers of foreign-language articles to file English translations with local postmasters as a condition of using the mails.19

During the war, the federal government monitored and prosecuted war opponents with an enthusiasm that far surpassed Lincoln’s, notwithstanding the fact that World War I, unlike the Civil War, posed little threat to national survival.20Judicial reaction to federal prosecutions shaped the modern American debate over freedom of speech. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes and his colleagues on the U.S. Supreme Court crafted the prevailing test of the day, which focused on the likely effect of speech rather than its content. “The question,” said Holmes, “… is whether the words … create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to protect … [There is] no ground for saying that success alone warrants making the act a crime.”21 Holmes’s effects-based test echoed Lincoln’s attempt to justify Vallandigham’s arrest.

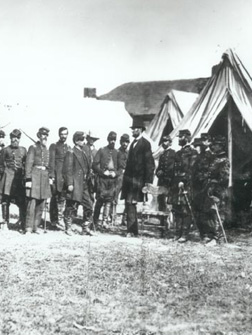

Photo by Alexander Gardner, Oct. 3, 1862, Antietam, Lincoln with General McClellan.

Learned Hand, a New York federal district court judge who later became nationally renowned when he sat on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, led a small group of jurists who argued for regulation of speech based on content rather than on its likely results. Hand argued that judicial prediction of likely effects of speech was too uncertain a foundation on which to base arrests and detentions. “To assimilate agitation, legitimate as such, with direct incitement to violent resistance,” said Hand, “is to disregard the tolerance of all methods of political agitation which in normal times is a safeguard of free government.”22 Hand’s approach did not prevail during the war but it later gained favor over Holmes’s approach and even caused Holmes to reconsider and modify his position.23

To their credit, Wisconsin lawmakers took a relatively tolerant attitude toward wartime dissent. In 1918 the Wisconsin Legislature passed a bill closely modeled on the federal Espionage Act but added a sunset provision automatically terminating the law at the end of the war. In signing the bill Governor Emanuel Philipp, a conservative, warned that the bill must be “strictly construed” so that it would not “in any measure interfere with the free discussion of the affairs of this government.”24 Wisconsin federal prosecutors and judges, particularly in the heavily German-American Eastern District of Wisconsin, were less enthusiastic about prosecuting under the Espionage Act and interpreting the Act broadly than were their counterparts elsewhere.25

Nevertheless, there were several controversial cases and convictions in Wisconsin. Circuit court judge John Becker of Monroe was removed from office and sentenced to a year in prison for criticizing the war as “a rich man’s war” and warning farmers to “beware of war taxes.” Becker’s conviction was later reversed, but the prosecution ended his judicial career and irreparably damaged his life.26Louis Nagler of Madison received a two-and-a-half-year sentence merely for objecting to the YMCA’s and Red Cross’s solicitation of donations for war relief, criticizing the agencies as a “bunch of grafters” and arguing that the war was being run by “a bunch of capitalists.” Nagler’s treatment provoked protest from Wisconsinites across the political spectrum. Federal authorities dropped the case on appeal, but a residue of bitterness remained long after the case concluded.27

Victor Berger of Milwaukee, the leader of the Social Democratic Party in Wisconsin and the most well-known American Socialist after Eugene Debs, was perhaps the most prominent wartime target of federal prosecutors. After the United States entered the war Berger published a series of editorials in his newspaper, the Milwaukee Leader, criticizing the war effort. Among other things, Berger criticized “the English lion [and] the American eagle [as] animals that prey … [as] proper emblems of the capitalist rule,” and asked, “Why should we permit our boys to be killed … because English profiteers make money out of this war?” Such articles prompted Albert Burleson, the federal postmaster general, to suspend the Leader’s access to the mails. Burleson made clear that “anything calculated to dishearten the boys in the army or to make them think this is not a just or righteous war” would be suppressed.28 The U.S. Supreme Court upheld Burleson. It put the burden on Berger to show that his remarks were not seditious rather than on the government to show that they were – a decision that a leading First Amendment scholar later described as a low point for freedom of the press and as “utterly foreign to the tradition of English-speaking freedom.”29

Not content with blocking distribution of the Leader, federal officials also prosecuted Berger under the Espionage Act for his criticism of the war effort. Prosecutors chose to bring their case in Chicago instead of Milwaukee, where no jury was likely to convict Berger. They obtained a conviction and in early 1919 Berger was sentenced to a 20-year prison term.30 In the meantime Berger had been elected to Congress, but after his conviction the House of Representatives voted 311-1 to deny him his seat. Only one colleague, Rep. Edward Voigt of Sheboygan, supported Berger. Voigt quoted Lincoln among others in arguing that free speech is “[t]he greatest single blessing enjoyed by the people of these United States” and that “many men are now in prison who have done nothing more than to express their opinions.”31

Defiant Milwaukeeans again elected Berger to Congress, but he was again denied his seat. This time five more representatives joined Voigt in defending Berger. One of them again invoked Lincoln, acidly stating: “We must all concede that were Lincoln on earth today with such an utterance he would be serving a sentence in the penitentiary along with Eugene Debs.” Berger was again elected to Congress in 1922 after the U.S. Supreme Court reversed his conviction because of a procedural error during his trial, and this time Berger was seated.32

Lincoln and Modern Views of Free Speech in Wartime

Since World War I, restrictions on dissent and speech in wartime have not disappeared but have relaxed considerably. This is perhaps due in part to an increasing tendency of Americans in recent decades to view liberty and justice in terms of the right to individual expression and self-fulfillment instead of as a tool for promotion of a common good.33 In recent decades Wisconsin courts have generally struck down governmental efforts to limit free speech, for example, university codes against offensive speech and flag desecration laws.34

The post-9/11 era and the Iraq war have once again revived the debate as to how to strike the balance between civil liberties and national security. The federal government’s monitoring of private speech and detention of suspected terrorists without trial have generated substantial opposition and controversy. Several legal scholars have drawn explicit parallels to the debates of the Civil War. Some have argued, as Lincoln did, that the president’s oath to preserve the nation and the Constitution gives the president broad discretion to suspend civil liberties in times of emergency and to define emergencies that warrant suspension.35 Others, perhaps a majority, have sided with Lincoln’s critics and have argued that one cannot destroy the Constitution in order to save it.36 It remains to be seen whether the events of Sept. 11, 2001, will permanently affect the scope of civil liberties in America, but the modern American emphasis on individual fulfillment through freedom of expression – a sentiment endorsed by Wisconsin courts – will likely be a powerful force for preserving our basic liberties.

Endnotes