“Lawyers fear that help won’t be confidential and someone will find out, and if someone finds out, their practice and livelihood will be ruined. Those are critical errors in their thinking.”

Linda Albert, program manager, Wisconsin Lawyers Assistance Program (WisLAP), State Bar of Wisconsin. Photo: Andy Manis

The sixth day of January 2007 is a significant date for attorney Anne Renc. That’s the day she stopped drinking alcohol. Renc was halfway through her second year at the University of Wisconsin Law School when it hit her. “I realized that if I didn’t get a handle on this, I wasn’t going to be a lawyer.”

Alcoholism was in the family genes. “Drinking became a crutch for me to deal with the stress of law school,” said Renc, now an assistant state public defender in Stevens Point. “I wouldn’t say law school encouraged drinking, but there was a perception that drinking was part of how you dealt with pressure, at least in a colloquial word-of-mouth way.”

For the first half of her law school career, Renc drank heavily, even during final exam periods. She didn’t drink every day. But when she did consume alcohol, she drank to excess. “The first year, I was doing what I was supposed to do, maybe not as well as I could. But I was getting by,” she said. “Things really started to fall apart the fall semester of my second year, though. I was having a hard time getting to class and doing the work.

“Looking back now, I don’t think I would have been able to finish school if I kept drinking. Once I was ready to admit I had a problem, I knew what I had to do.” She entered an alcohol and drug treatment program.

Acknowledging a Problem

Renc graduated three semesters later, in 2008. When she applied for her law license, she disclosed her treatment to the Wisconsin Board of Bar Examiners (BBE), which assesses an applicant’s character and fitness to practice law. “I got a letter from a psychiatrist and put the BBE in touch with the people helping me in recovery, so they could ensure I was getting better and was fit to practice.” In June 2008, Renc was admitted to practice law and became a member of the State Bar of Wisconsin.

She has maintained her sobriety since January 2007, and gets professional help for depression and anxiety, mental health issues that first surfaced when she was in high school but were never treated. “Those mental health episodes were present through law school and remain present today, but I never sought professional help before.”

“We have to change the perception that substance abuse or mental health issues only apply to other people, or people on the street.”

Anne Renc, U.W. 2008, assistant state public defender, Stevens Point. Photo: Kevin Harnack

“It’s humbling to admit you have a problem you can’t fix on your own,” Renc said. “It’s even harder for lawyers because we are in the business of fixing things. But we have to change the perception that substance abuse or mental health issues only apply to other people, or people on the street. If we don’t realize that those things apply to us, as lawyers, things won’t change and people won’t get better.”

While Renc is among a small minority of lawyers who openly acknowledge prior or existing substance or mental health conditions, problem drinking and mental health concerns are significant among lawyers, especially younger ones, according to a recent and comprehensive landmark study of U.S. lawyers. The study, called “The Prevalence of Substance Use and Other Mental Health Concerns among American Attorneys,”1 also indicates that many lawyers are not seeking the help they need, for the wrong reasons.

“Lawyers fear that help won’t be confidential and someone will find out, and if someone finds out, their practice and livelihood will be ruined,” said Linda Albert, program manager of the Wisconsin Lawyers Assistance Program (WisLAP), a State Bar of Wisconsin program, who helped lead the study. “Those are critical errors in their thinking.

“First, programs like WisLAP are confidential. Second, seeking help voluntarily does not, by itself, impact someone’s law license. It just allows them to be healthier, minimizing the risk of breaking ethical rules. We want to dispel the misconceptions, eliminate stigmas attached to mental health and substance abuse issues, and encourage lawyers to get the help they need before bigger problems arise.”

Landmark Study: First Empirical Study in 25 Years

Anecdotally, there’s a widespread belief that lawyers have significant substance abuse problems or mental health disorders, more so than other professionals or the general population. But the last time anyone conducted an empirical study was 1990, when researchers surveyed approximately 1,200 attorneys in Washington State to determine that lawyers there had significantly higher rates of problem drinking and depression than others outside the profession.

“The problems are far reaching and consistent. There’s no one group within the profession that seems to be immune to behavioral health problems, and the problems are significant.”

Patrick Krill, director, Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation’s Legal Professional Program, Center City, Minn.

“The available data was so limited, and so outdated. In my opinion, it was no longer credible,” said Patrick Krill, director of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation’s Legal Professionals Program in Center City, Minn., a rehabilitation center for attorneys, judges, and other legal professionals with addiction and co-occurring mental health issues. Krill is also an attorney and a licensed drug and alcohol counselor.

“That was a real frustration,” says Krill. “It was difficult to raise awareness and promote change in the profession with outdated information. We needed reliable data to illustrate the significance of this problem.”

To that end, Krill spearheaded a landmark study on substance abuse, depression, and anxiety concerns among U.S. lawyers. WisLAP’s Albert, also a member of the American Bar Association’s Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs, spent months helping Krill and others form a collaboration. Recognizing the need for reliable data, the ABA approved a resolution to partner on the project. The Hazelden-ABA collaboration resulted in findings that were officially released in the Journal of Addiction Medicine, and were announced Feb. 6 at an ABA-sponsored press conference.

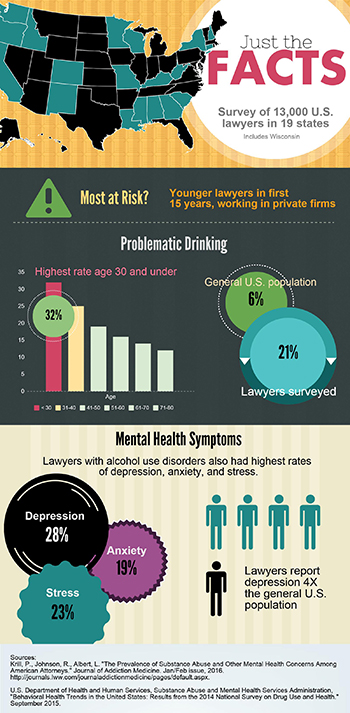

With the help of 15 state bar associations, including the State Bar of Wisconsin, almost 15,000 lawyers from 19 states in every region of the country completed an anonymous 2015 survey assessing alcohol use, drug use, and symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health concerns. Of those, nearly 13,000 respondents met the criteria for inclusion in the study: lawyers had to be licensed in the United States and currently employed in the legal profession as an attorney or judge. Close to equal numbers of men and women participated, identifying their respective age groups, job position types, and whether they worked in private firms, state bar associations, government or nonprofit organizations, or other working environments.

“This is a huge data set,” said Krill. “We wanted to get a clear picture of what’s going on with licensed and employed attorneys and judges in America, and this is a representative sample from all corners and regions of the country, from the biggest metropolitan areas to the smallest towns. What we found is that the problems are far reaching and consistent. There’s no one group within the profession that seems to be immune to behavioral health problems, and the problems are significant.”

Alcohol Abuse: 21 Percent Report Problematic Drinking

Approximately 11,300 participants completed a 10-question instrument, known as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-10), which screens for different levels of problematic alcohol use, including hazardous use, harmful use, and possible alcohol dependence. The test identifies quantity and frequency of use, and asks whether an individual has experienced consequences from drinking. Of the approximately 11,300 respondents, 21 percent scored at a level consistent with problematic drinking. Alcohol abuse was identified in 25 percent of men respondents, compared to 16 percent of women.

Learn More

Join Linda Albert and other panelists at the Annual Meeting & Conference in June to gain an understanding of the issues young lawyers face and, when not addressed, how they increase risk for ethical violations.

Staying Fit to Practice: How Young Lawyers Meet Their Challenges

State Bar Annual Meeting & Conference, June 16-17, 2016, Green Bay

amc.wisbar.org

Of those identified as working in private firms, approximately 23 percent were considered problem drinkers, the highest of any working environment other than lawyers working in bar associations, at 24 percent. (In some states, not including Wisconsin, the state bar handles lawyer disciplinary matters and has staff attorneys who work on those cases or on other legal matters.)

Of the private-law-firm lawyers identified as junior associates, 31 percent identified as problem drinkers, the highest compared to senior associates (26%), junior partners (24%), managing partners (21%), and senior partners (18.5%). Thus, the data suggests that a higher rate of lower-level lawyers engage in problem drinking behavior, and problem drinking slightly decreases as they move up the law firm chain.

For lawyers in other working environments, the rate of alcohol use disorders is also relatively high under the AUDIT-10. Of those identified as in-house, governmental, public, or nonprofit lawyers, 19 percent were considered problem drinkers. Approximately 19 percent of those identified as sole practitioners had an alcohol use disorder. Approximately 18 percent of the in-house corporate or for-profit organization lawyers were considered problem drinkers, and approximately 16 percent of judges identified as having an alcohol problem.

When sifting data by age and years of practice, it becomes clearer that younger lawyers are struggling the most with alcohol abuse. Respondents identified as 30 years or younger had a 32 percent rate of problem drinking, almost 1 in 3, higher than any other age group. Those attorneys ages 31-40 reported a 25 percent rate of problem drinking. Starting at age 51, the percentages fall below 20 percent.

Problem drinking also correlates with years of practice, based on the data. Of the lawyers who reported working for 0-10 years, approximately 28 percent of them reported problem drinking behavior, compared to those with experience of 11-20 years (19 percent), 21-30 years (16 percent), and 31-40 years (15 percent).

Click on infographic to view larger version.

According to Krill, that data is very significant.

“The old data suggested that the longer somebody stayed in the profession, the more likely they were to become a problematic drinker,” said Krill. “That aligned with a perception that the legal culture sort of promotes drinking and it’s a stressful profession, so the more exposure a person has in terms of years, the more likely a problem would develop. We found that that’s not true at all. It’s the reverse now.”

Krill said the data shows the risk of developing a drinking problem is highest for attorneys in their first 10 years of practice. “Being in the early stages of a legal career is strongly correlated with a heightened risk of developing an alcohol use disorder,” Krill said.

Approximately 11,500 participants answered the first three questions of the AUDIT-10, allowing a subset test known as AUDIT-C to be performed. The AUDIT-C, recently used to gauge problem drinking among U.S. physicians, measures frequency and quantity of alcohol consumed. It does not ask about consequences. It simply asks how often an alcohol drink is consumed, how many drinks are consumed in a typical day, and how often six or more drinks are consumed on one occasion.

Of the 11,500 AUDIT-C respondents, 36 percent scored consistently with problematic drinking. That’s well more than double the 15 percent of surgeons and physicians screening positive on an AUDIT-C in 2012, and triple the percentage of highly educated workers sampled in 2003 under the same test. Although not an apples to apples comparison, a recent study of substance abuse and mental health issues among the general U.S. population found that about 12 percent of young adults (ages 18-24) had an alcohol use disorder, and about 6 percent of adults ages 26 or older had an alcohol use disorder.2

Most notably, 44 percent of lawyers reported that their use of alcohol was problematic during the 15 year-period that followed graduation from law school. Another 28 percent reported problematic use that started before law school, and 14.2 percent said their problem drinking started in law school.

Drug Abuse: Picture Less Clear

Researchers used the 10-question Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) to gauge low, intermediate, substantial, and severe drug abuse among participant lawyers and judges. Drug abuse includes the nonmedical use of illegal substances or prescription drugs, or the use of prescribed or over-the-counter medications in excess of prescribed or directed amounts. Only 27 percent of all respondents completed the DAST, a much smaller sample than the AUDIT, which had almost full participation.

“After two years, I had to quit my job without knowing what job I would go to next.”

In law school at Tulane University, Elizabeth Cavell decided she wanted to be a career public defender. After graduating in 2009, she landed a public defender job in Pueblo, a small Colorado town. “On my first day, I was scheduled to appear in court and already had close to 100 cases transferred to me.”

In law school at Tulane University, Elizabeth Cavell decided she wanted to be a career public defender. After graduating in 2009, she landed a public defender job in Pueblo, a small Colorado town. “On my first day, I was scheduled to appear in court and already had close to 100 cases transferred to me.”

As days, weeks, and months passed, the pressure grew. “I really believed in what I was doing; I loved my colleagues and the mission we were trying to accomplish,” she said. “But no matter how hard or how many hours I worked, I started having a feeling of dread that I wasn’t doing a good enough job. I was trying to develop skills as a new lawyer and be competent with more than 200 cases.”

Cavell wasn’t just a new lawyer with an overwhelming caseload. She was a young adult with the natural stress of life changes. She was in her 20s, in a new town. She didn’t know anyone, besides her fiancée, and she was carrying a huge student loan debt, which “loomed like a cloud over everything.”

“That’s a steady hum of panic in the background, trying to pursue a career in the public sector and not making enough money to pay those debts anytime soon,” she said. “There were many different factors and stressors that were tugging at me, and the demands of the job left little room for other things in life. I wasn’t taking care of myself. I wasn’t available in my home life and my relationship.

“I was constantly in a state of panic and dread about all my work responsibilities. It’s very hard to live like that,” she said. “I let it get to a point where I was in crisis.”

Cavell had developed a debilitating mental health condition in the form of anxiety. She talked with her supervisors and colleagues, and they did what they could to ease her caseload. But it wasn’t enough. “After two years, I had to quit my job without knowing what job I would go to next,” she said.

“It’s hard to admit that you need help to manage something like that. I kept thinking I should be able to deal with it on my own,” she said. “But I’ve taken advantage of mental health counseling and therapy to talk through my biggest stressors and how I’m doing with anxiety. I’ve learned tools to deal with stress and anxiety that don’t come naturally. Things are much better now.”

She and her fiancée, now husband, moved to Madison in 2012. She took a job as staff counsel for the Freedom from Religion Foundation. “It’s a better fit for me. It just took a while to figure out how I could stay in the public sector in a job that fit with the life I wanted. I’m still very much aware of my mental health management. Life doesn’t get any less stressful, but there are tools to help lawyers cope with it.”

Cavell is also a WisLAP volunteer. She helps other lawyers in need of assistance, benefitting from the perspective of her own struggles. Looking back to her time in Colorado, she wishes she would have reached out for help sooner. “We can be our worst enemies in the sense that it’s hard to ask for help.

“When I did reach out, the advice I got was: ‘It’s just a job. Your health comes first.’ Reaching out is the only way to get that perspective when you are stuck in your own moment of time.”

Elizabeth Cavell, Tulane 2009, Freedom From Religion Foundation, Madison

“We can speculate that a lower sample means drug use is not as prevalent as alcohol use among lawyers, and that’s logical,” Albert said. “But you may also have lawyers who don’t want to voluntarily disclose information about illegal drug use, even though the survey was confidential and anonymous.

“They would likely be more open to answering questions about alcohol, since alcohol is legal. So the picture is less clear. Obviously, any indication of drug abuse among lawyers is concerning,” she said.

Of the 3,419 participants that completed the DAST, 0.1 percent reported severe drug use. Three percent reported substantial drug use, 21 percent reported intermediate use, and 76 percent reported low use. Albert says low use means low quantity and frequency with little or no consequences. The highest rate, 16 percent, reported using sedatives, which include depression, anxiety, or sleeping medications. About 10 percent used marijuana or hash, and 6 percent reported opioid use.

Krill said the significant number of participants reporting low and intermediate drug abuse is troubling when one considers the proliferation and addictive nature of today’s prescription drugs, such as opioid-based painkillers. “If a lawyer is abusing prescription medications, it can quickly turn to ‘substantial’ or ‘severe’ use,” Krill said. “And given the even higher stigma associated with drug use, lawyers may be even more hesitant to seek help.”

Depression, Stress, and Anxiety: 28 Percent Report Concerns with Depression

Approximately 11,500 participants completed a 21-question Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21). Approximately 61 percent and 46 percent reported experiencing concerns with anxiety and depression, respectively, at some point in their career. Respondents also reported experiencing social anxiety (16 percent), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (12.5 percent), panic disorder (8 percent), and bipolar disorder (2.4 percent). More than 11 percent reported suicidal thoughts during their career. Three percent reported self-injurious behavior, and 0.7 percent reported at least one suicide attempt during the course of their career.

Approximately 28 percent reported concerns with mild or high levels of depression, males at a higher rate than females, and 19 percent reported mild or high levels of anxiety, females at a higher rate than males. Of all respondents, 23 percent reported mild or high levels of stress, which involves mental or emotional strain attached to a certain event. Anxiety involves a constant or consistent feeling of worry.

Like the rates associated with alcohol use, mental health conditions were higher in younger or less experienced attorneys, and generally decreased as age and years of experience increased. The study also revealed significantly higher levels of anxiety, depression, and stress among those with problematic alcohol use, meaning mental health concerns co-occurred with an alcohol use disorder.

“We see that many lawyers are drinking as a way to cope with stress, anxiety, or depression. Others may experience those mental health conditions as a direct result of their drinking,” Albert said. “In both equations, alcohol is a common denominator that, if removed, will improve a lawyer’s health and wellness.”

The annual study of substance abuse and mental health issues among the general U.S. population found that more than 9 percent of those ages 18-24 experienced a major depressive episode in 2014 – symptoms lasting two weeks or longer – compared to 7 percent of those ages 26-49, and about 5 percent of those ages 50 and older.3

Barriers to Treatment

Only 7 percent of participants report that they sought treatment for alcohol or drug use, and only 22 percent of those respondents went through programs tailored to legal professionals. But the participants who went through treatment programs tailored specifically for legal professionals had significantly lower (healthier) AUDIT scores than those who sought treatment elsewhere. This suggests that programs with a unique understanding of lawyers and their work can better address the problems.

Respondents were asked to identify the biggest barriers to seeking drug or alcohol treatment. About 67.5 percent said they didn’t want others to find out, and 64 percent identified privacy and confidentiality as a major barrier. Approximately 31 percent noted concerns about losing their law license, and 18 percent said they didn’t know who to ask or didn’t have the money for treatment. Respondents raised the same concerns when asked about the barriers to seeking help for mental health issues. Approximately 55 percent said they didn’t want others to find out, and 47 percent raised confidentiality and privacy concerns. Another 22 percent said they didn’t know who to ask for help.

Close to 70 percent of respondents said alcohol and drug addiction or mental health topics were not offered in law school. Approximately 84 percent said they were aware of lawyer assistance programs (LAPs), but only approximately 40 percent said they would be likely to use those services if the need arose. Again, privacy and confidentiality concerns were cited as the major barrier to seeking help through LAP programs.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Issues: Why So High?

Albert and Krill say that question cannot be answered definitively. But the data will help substance and mental health professionals formulate possible answers. They suspect lawyers may have higher rates than other professionals or educated populations based on the inherent stress of the job. As advocates and counselors, lawyers are trusted to handle important matters with high stakes for clients.

“This whole thing would have been better if I had a heart attack.”

Matthew MacWilliams graduated from Hamline University School of Law in 1999 and worked in different Minnesota-based firms before returning to Madison, his hometown. He was working at a Madison firm for more than year when he started to feel like something was wrong.

Matthew MacWilliams graduated from Hamline University School of Law in 1999 and worked in different Minnesota-based firms before returning to Madison, his hometown. He was working at a Madison firm for more than year when he started to feel like something was wrong.

“I had tremendous anxiety. I was obsessed with time and perfectionism, beyond what typical lawyers experience,” he said. “At first, I just kept working and ignored it. My father, who has since passed away, told me to suck it up. That’s what I tried to do. I saw a counselor, but I wasn’t giving him the full picture. And I just kept thinking that my time there was being wasted. These are hours I could be billing for the firm.”

Then in September 2005, something happened. Matthew made a nonprejudicial error on a file that was resolved with a phone call. One of the partners went through the file with him, to see what went wrong. “I remember my hands were shaking so badly. I could not handle the fact that I made a mistake and was being ‘talked to,’” he said. “I realized that this wasn’t normal. I understood that something was wrong.”

Ultimately, he was diagnosed with obsessive compulsive disorder. He had to take time off. But when his doctors cleared him to return to work, the firm imposed conditions. He was not to have contact with clients or file paperwork. “Now I understand why. They had to protect the clients. But at the time, I felt they were taking everything away from me, and they didn’t trust me to do anything. It didn’t sit right.”

“What I really needed was more time off. But I was listening to my father and my doctor, who were telling me to go back to work. What I needed to do was listen to myself.”

MacWilliams resigned from the firm in November 2005, and his condition only worsened. He was hospitalized on and off through 2006. But he says he still wasn’t getting the treatment he needed. He was on heavy medications. He slept 20 hours per day and didn’t eat. He was driving off the road.

MacWilliams explained that his mental health declined to a point where he engaged in self-injurious behavior and was terrified of the thought of returning to work as a lawyer.

Seeing no improvements in his mental health, MacWilliams’ wife started advocating aggressively on his behalf. With her help, he found the right team of doctors to address his severe condition, and things have improved. “I have not been this happy in 20 years,” he said.

He started attending training through WisLAP, and now he’s a WisLAP volunteer. But he has no desire to practice law again. He’s going back to school for a master’s degree in clinical counseling.

“What the WisLAP program taught me was that I like helping people, and I want to help lawyers,” he said. “But I can’t practice law. The things that happened to me don’t have to happen. But I just know there are lawyers out there who may be feeling this way, and they don’t want to come forward.

“I’ve said this many times. This whole thing would have been better if I had a heart attack. If you have a heart attack, people say ‘you are working too hard.’ But if something is wrong with your brain, lawyers distance themselves. They don’t want to see the consequences of a mental health problem.”

Matthew MacWilliams, Hamline 1999, master’s degree candidate, clinical counseling. Photo: Shannon Green

They can also be susceptible to compassion fatigue, characterized as the “cumulative physical, emotional and psychological effects of being continually exposed to traumatic stories or events when working in a helping capacity.”4 No doubt lawyers seek outlets to deal with pressures and stress, and two avenues exist: positive outlets, like exercise, and negative ones, like substance abuse.

Albert and Krill say lawyers also can be somewhat isolated, or enabled by the profession’s drinking culture. Physicians, for instance, work in community environments where people will notice problematic behaviors. That’s not always true for lawyers, especially solo practitioners. There may be no one asking them if they’re okay, Albert said. Or staff members may cover for lawyers, fearing any consequences that impact the lawyer will also impact their own employment.

In addition, younger lawyers are entering the profession with higher rates of student loan debt and fewer job opportunities, aside from the normal stress of learning to be a practicing lawyer. Those additional factors may contribute to the higher rates of substance abuse and mental health concerns among younger lawyers with fewer years of practice, Albert says.

“Newer and younger lawyers may be forced to take or work in jobs they don’t like, because they just need the work,” Albert said. “Some have to put off marriage or having families because of financial concerns. There is real stress that compounds from that, stress that can lead to depression, anxiety, and substance abuse issues. It’s logical to conclude that those issues could arise.”

Drinking has become (or always has been) socially acceptable in the legal profession, Krill and Albert note. Many law students drink to blow off steam, as Renc explained. Those habits may carry over into law practice, where alcohol can be viewed as an acceptable pressure valve. It’s also a vehicle to celebrate success, face defeat, or network with clients, potential clients, or other lawyers. The lawyer drinking culture is even popularized through various TV law dramas, perpetuating the perception that drinking is just what lawyers do. How many shows end with two lawyers sipping scotch, discussing the case? How many times do you hear TV lawyers utter the phrase: “I need a drink.” Moderate and responsible alcohol consumption aside, what happens when lawyers actually feel the “need” to drink?

When drinking becomes problematic, or lawyers develop mental health conditions, the pervasive stigma associated with those issues creates a barrier for lawyers to seek help, Krill says. “There’s a lot of stigma attached to substance use disorders and mental illness. Because a lawyer’s reputation is so important, there’s a fear in admitting vulnerability or weakness, or admitting that we are struggling,” he said. “And those fears can be justified, because this can be a harshly judgmental and highly competitive environment. But when this data comes out and people realize how many lawyers are struggling, it will be difficult to view these issues through such a judgmental lens. That’s my hope anyway.”

Barriers to Early Intervention: Searching for a System-wide Solution

Albert says fighting the stigmas of mental health and substance abuse needs to happen on many levels. “It needs to be a systems approach,” she said. “From law schools to bar associations, from licensing and disciplinary agencies to employers and lawyer assistance programs, all legal stakeholders must work together to address the problem,” she said. “We still have this kind of blame-shame bias. We can break those stigmas by educating people, and helping them understand that it’s smarter to get help.”

Renc understands. She tells her story openly because she wants fellow lawyers to know that seeking help is the right decision. Her decision to get treatment in law school undoubtedly saved her legal career, she says, and her disclosure to the BBE did not prevent her from obtaining a law license. That is, law students with substance abuse or mental health issues should not wait to get help.

Jacquelynn Rothstein, director of the BBE, says that when applicants disclose drug, alcohol, and mental health issues, one of the first questions the BBE considers is how that problem has affected an applicant’s life and how the applicant has addressed it. “We also look at whether those conditions affected an applicant in an employment or academic setting, whether there were arrests, convictions, or other problematic behaviors. An applicant’s conduct and behavior are an integral part of determining whether an applicant is fit to practice,” she said.

“If an applicant is being treated and there’s evidence of treatment after having a history of problematic behavior, then that in and of itself may not prevent the applicant from getting admitted. That is true,” she said. “But if you have an ongoing active history of drug, alcohol, or mental health issues, and you have not treated it, that may well be a problem for the applicant. Obviously, we want to encourage those in need of treatment to obtain it.”

Although Rothstein acknowledges that disclosing a drug, alcohol, or mental health-related concern alone may not bar applicants from the practice of law, she is quick to point out that each case is different. “We look at it on a case-by-case basis. There is no blanket approach to addressing these issues. There are numerous factors in determining an applicant’s character and fitness to practice law.”

webXtra

<iframe src="//www.youtube.com/embed/5OdvaHMnE6I?rel=0&autohide=1" width="300" height="169" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

The first empirical study in 25 years confirms lawyers have significant substance abuse and mental health problems – with younger lawyers most at risk. And, many lawyers are not seeking the help they need, for the wrong reasons. Linda Albert, manager of the State Bar’s Wisconsin Lawyer Assistance Program (WisLAP), was one of the study’s authors. In this video, she talks about the key findings, why lawyers are hesitant to seek help, and what the study means moving forward. Read more.

As of 2011, the BBE is also authorized to grant conditional admission for applicants whose record may otherwise warrant denial but who agree to certain conditions and demonstrate ongoing recovery and the ability to meet the competence and character and fitness requirements. In 2014, seven applicants were conditionally admitted based on substance use-related issues, one was conditionally admitted based on mental health issues, and one had both substance abuse and mental health issues.

“Conditional admission may be another option for applicants who are willing to do what they need to do,” Rothstein said. “We certainly are not trying to discourage people from getting treatment. But we also don’t want to send the message that abusing drugs and alcohol is okay. Because it isn’t.”

Importantly, an individual is conditionally admitted and the terms of the conditional admission are confidential, with some exceptions. In addition, conditions may require monitoring or other involvement with WisLAP, a confidential program for lawyers and judges whether they seek help voluntarily or are mandated to participate. But what people may not know is that WisLAP is also open to law students, and the data shows that law students may need a place to turn.

Another recent study of law students from 15 law schools found very high rates of binge drinking, marijuana, and prescription drug abuse, in addition to high rates of depression and anxiety. Approximately 79 percent of those using prescription drugs without a prescription used Adderall, a stimulant, to help them concentrate and study longer.

When asked what factors would discourage students from seeking help for drug or alcohol problems, more than 60 percent identified a potential threat to bar admission, job, or academic status. The study’s authors concluded that attitudes and cultures must change; students must be encouraged to get help rather than keeping mental health and substance abuse issues secret.5

Office of Lawyer Regulation: Substance Abuse, Mental Health Issues Underlie Grievances

Some lawyers fear losing their law license if someone finds out they are seeking treatment for drugs, alcohol, or mental health-related issues. The Office of Lawyer Regulation (OLR) investigates grievances against lawyers to determine if they have violated their ethical duties under the Wisconsin Rules of Professional Conduct for Attorneys. OLR Director Keith Sellen says many grievances are sent to the OLR, not because a lawyer has decided to seek treatment for their problem, but precisely because a lawyer has not sought help and the condition starts affecting the lawyer’s ability to practice law.

Joe Forward, Saint Louis Univ. School of Law 2010, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6161.

Joe Forward, Saint Louis Univ. School of Law 2010, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6161.

“We see a lot of grievances where the lawyer’s practice is struggling because of substance abuse, depression, or some other medical incapacity,” Sellen said. “A lot of these cases involve an expansive pattern of failure to act with diligence on behalf of a client, or failure to communicate. In other words, a chemical dependency may be preventing them from doing the work required of the representation.”

Sellen noted that the OLR often sees cases after it’s too late. “If lawyers are able to identify the concern and cause earlier, before it becomes a real problem, and they are willing to seek help through WisLAP’s confidential program, then a lot of these cases where conduct gets out of control could be avoided.”

On the flip side, once a lawyer has fallen through the cracks and the OLR gets involved, there can be ways to get back on track. “When lawyers are referred for mandatory treatment and monitoring, those cases are assigned to WisLAP. We’ve had success with lawyers being able to recover and restore themselves and get their practices back up and running. So WisLAP works in two ways. It’s preventative and restorative.”

Sellen acknowledges that lawyers may have reasons for not seeking help, “but those fears should be overcome by the potential ramifications of not seeking help. The bottom line is that you can do this in a way that’s confidential,” he said. “WisLAP does not report that to the OLR. This is an appropriate policy because we want to encourage lawyers to take advantage of the confidential program,” he said.

Moving Forward: Defining a Response

“I can’t say that there was any good news that came from this study,” Krill said. “The good news comes from what we can do with it. Now we know the scope of the problem. Now we can define a response, and develop more informed strategies for dealing with it.”

Krill said law schools could use the data, especially data on the struggles of young lawyers in the early stages of their careers, to incorporate health and wellness into their law school curriculums. Bar associations and continuing legal education (CLE) accreditation agencies such as the BBE could evaluate CLE requirements to determine programming that addresses substance abuse and mental health issues.

For Wisconsin attorney Paula Davis-Laack, who now runs the Davis Laack Resilience Institute, the data informs her work helping lawyers on stress management, burnout prevention, and resilience. A former practicing lawyer, she earned a master’s degree in applied positive psychology and is trained in the study of resilience. She teaches specific skills to help lawyers deal with adversity and stress.

“I’ve been looking for this type of data,” said Davis-Laack, who practiced law for seven years before experiencing burnout. “It will help as I approach law schools and law firms interested in my training and workshops on resilience. They want to see data and research that says lawyers need these skills.”

“I do some work with law schools and the students are really craving this type of information,” she said. “They want to learn how they can have a sustainable career in this profession, especially when they hear stories about the high rates of substance abuse, depression, and anxiety among lawyers.”

Davis-Laack says that law firms are also interested in her work on resilience as they lose second- or third-year associates. “They don’t have the coping mechanisms to get through uncertainty in the first few years of practice. Suddenly they hit a road bump, and they think a new firm will fix the problem.”

Existing research also shows that lawyers are not the most resilient bunch, Davis-Laack says. “Lawyers tend to be somewhat thin-skinned. They don’t like to be called out and corrected. When challenges and adversity happen, they don’t have the right coping skills. They tend to resort to negative behaviors like excess drinking. That’s typically what I’m finding, and now we are seeing that in this new data.”

Richard Brown, former chief judge of the Wisconsin Court of Appeals and a former member of the ABA Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs, says this data underscores the importance of educating judges and lawyers about the warning signs and the resources available to help them.

“Part of the problem is that people with depression, anxiety, or substance abuse issues don’t often know they need help. They may be unhappy, they may be drinking too much, but they don’t consider themselves to need help. To me, part of the problem is getting the horse to water. That means alerting people that they should seek help if they start seeing the symptoms. A lot of it is education.”

Judge Brown noted that when he was on the ABA commission several years ago, Wisconsin was selected as part of a pilot project to conduct judicial roundtables, where judges would get together and discuss the stresses of the day-to-day job. At first, it didn’t work.

“But we kept doing it and finally, we got to a point where judges were finding this to be very helpful. We aren’t talking about case law. We are talking about what to do when something is bothering you. How do you cope with the stress of the job? You hear people talking and realize we are all dealing with the same kind of issues. And we are educating each other on what might be considered a problem.”

Brown said a judicial roundtable was held at the Wisconsin Judicial College last year. “Everybody came away saying we should do this again next year. Maybe the lawyers could do something like that.” Albert says WisLAP has started doing just that – roundtable discussions with both lawyers and law students.

Krill, who spearheaded the study, likes where these kinds of ideas are headed. “While nobody can be excited about the specific findings, I am really excited about the impact this can have on the profession. Hopefully it can help us help a lot of people.”

Says WisLAP’s Albert: “This study triggers a call to action for all parts of the legal system to join together to make a positive impact. We need a cultural shift that puts health and wellness into the equation of lawyering. Ensuring lawyers are healthy is a central part of professional responsibility. But it’s going to require a collective effort among those who interface with lawyers throughout their careers.”

Endnotes

1 P. Krill, R. Johnson, L. Albert “The Prevalence of Substance Use and Other Mental Health Concerns among American Attorneys.” J. Addiction Medicine, Jan./Feb. 2016.

2 Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Serv., Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Admin. (Sept. 2015).

3 Dianne Molvig, The Toll of Trauma, 84 Wis. Law. 12 (Dec. 2011).

4 See Helping Law Students Get the Help They Need, 84 The Bar Examiner 4 (December 2015); see also Lawyer Assistance Programs: Advocating for a Systems Approach to Health and Wellness for Law Students and Legal Professionals, 84 The Bar Examiner 4 (December 2015).