Originally published in Wisconsin Lawyer Vol. 76, No.4 and Vol. 76, No. 6

Chief Justice Edward G. Ryan envisioned an organization that would allow lawyers to accomplish more by banding together than they could as individuals.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author and historian David McCullough once said, "History is who we are and why we are the way we are." As the State Bar of Wisconsin celebrates its 125th anniversary, it seems appropriate to examine our story of "who we are and why." This is the first article in a series that will look at some of the key events, issues, and personalities that have shaped the State Bar into what it is today.

The Bar's founding traces back to a meeting in the Wisconsin Supreme Court chambers in Madison on Jan. 9, 1878, three decades after Wisconsin attained statehood. One of the major instigators behind that gathering of 265 lawyers was Edward G. Ryan, supreme court chief justice. He welcomed the meeting's participants that day by stating, "I have long desired to see an efficient association of the state bar, and I am happy to think that the auspicious time has come at last when one may be formed."

Ryan envisioned a cohesive, professional organization that would allow lawyers to accomplish more by banding together than they could as individuals. "The bar as a body," he said, "can only have the influence which properly belongs to it, on professional subjects, through an organization by which it can speak with one voice."

Gaining a glimpse of what may have been on Ryan's mind as he made those remarks requires stepping back to view the evolution of Wisconsin's legal profession in the years leading up to 1878.

Stamina and Stature

By the mid-1800s, the federal census showed that Wisconsin had 471 attorneys serving a state population of 305,000. In those days, being a lawyer often demanded at least as much physical endurance as intellectual capability. The first quality enabled lawyers to get through the day. The second earned them widespread respect in their communities and beyond. Lawyers figured prominently in creating the new state's laws in 1848. In their hometowns, they "became natural leaders, and their help and influence were sought in all projects, not only political and governmental, but in business matters as well," writes James Anderson in Pioneer Courts and Lawyers of Manitowoc County, Wisconsin. Anderson practiced law and was a judge there in the late 1800s.

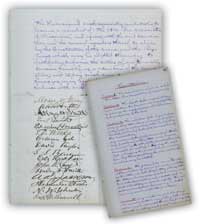

Founding members elected officers, including Moses Strong, president, and approved a constitution and bylaws at its organizational meeting on Jan. 9, 1878, all recorded by hand by Edwin Bryant, secretary.

In 1850, the state had six circuit court districts, with one judge assigned to each circuit. Traveling sometimes for days on snowshoes, horseback, wagons, sleighs, or on foot, judges made their way from one county seat to another. Shadowing them were troops of local lawyers who, by necessity, migrated to where the court work was.

Local residents loved it when the court came to town. Courtroom dramas were one of their few diversions, and lawyers made sure they didn't disappoint the spectators. In big trials, lawyers' arguments would go on for days, and those who put on the best show were perhaps as well known to the general public then as movie celebrities are today.

As years passed, the number of circuit districts multiplied and thus each circuit shrunk in size. Railroads and better roads also began to cross the state, so "riding the circuit" wound to an end. Still, practicing law remained physically arduous, except for attorneys in relatively urban Madison and Milwaukee.

For example, attorney Anderson describes the effort he put into preparing for one case. He left Manitowoc by train at 10 p.m. on a winter night in 1875. Four hours later, he arrived in New London, where he paced the depot for three hours to stay warm in subzero temperatures while waiting to catch a train to a station half-way to Green Bay. He arrived there to discover that the town clerk he needed to visit lived four miles out in the woods, so he tromped out to the clerk's cabin, often through knee-high snow. Anderson sat in the cabin all day and into the night copying records by hand. As it was too late to hike the four miles back to the train station, he slept in a spare room where the interior walls were, he says, "covered an inch deep with ice and white frost." In the morning he trekked to catch the train, repeated the same pattern of waits and layovers, and arrived that night back in Manitowoc, "thoroughly exhausted from work and loss of sleep," he writes.

Anderson's document-retrieval mission had consumed 48 hours. He notes that this was just one of many such instances in his career, and "(t)hey were the same in the experience of every lawyer in general practice."

The backgrounds lawyers brought to their practices varied considerably. Some had law degrees from back East or later from Wisconsin's still new law school, established in 1868. Rather than obtaining formal education, many had trained by serving as apprentices for a year or two with an older lawyer. But all that the statutes of 1849 required was that an attorney be a state resident and have "good moral character," which was assessed by a judge who then could grant the applicant permission to practice in his court.

Anderson writes that some "availed themselves of this easily obtained title of 'lawyer' to exact exorbitant fees for the most ordinary clerical or conveyancing work, especially from new arrivals to this country from Europe, under the pretext of professional knowledge."

Indeed, it was conditions such as these that, in part, spurred Chief Justice Ryan to call attorneys to meet in Madison on Jan. 9, 1878. By then, there were about 1,200 practicing attorneys statewide. Given the travel conditions of the day, it wouldn't be easy to get a sizable number of attorneys together in one place at one time. But Ryan and other key players had a plan.

Birth of the State Bar

The idea for a January meeting had taken root four months earlier, when many leading lawyers congregated in Madison for the funeral of federal judge J.C. Hopkins and a federal bar meeting to discuss his successor. Somehow their discussions veered to the prospect of organizing a state bar association.

A steering committee, chaired by Ryan, set the January meeting date, knowing that federal court would be in session at that time (it convened only a few times a year), drawing many lawyers to Madison. Thus, on Jan. 9, attorneys gathered there from Eau Claire, Hudson, La Crosse, Oshkosh, Chippewa Falls, Milwaukee, Green Bay, Prairie du Chien, Superior, and other points around the state.

Ryan's welcoming address spoke glowingly of the legal profession. "The peaceful social order, the integrity of the state, and every sacred personal right are in the keeping of our profession," he told his audience, adding that a "learned and independent bar is a condition of true civilization."

Those words, "learned and independent," signal where Ryan was heading with his proposed association. He decried the "knaves and fools" in the profession who lacked legal training, served their clients poorly, and threatened to pull down the entire profession with them. "The rule of admission is unfortunately lax," Ryan observed. "The doors are not ajar, but wide open."

Weeding out inept, unscrupulous lawyers and corrupt or "semi-corrupt" judges, as Ryan described them, was a paramount goal. And Ryan was clear as to where he felt that responsibility should lie. "All efficient steps to purge the bar must come from the bar itself," he said. In other words, keep legislators out of the business of disciplining lawyers, who would then be vulnerable to shifting political winds, rather than be subject to the rule of law.

With that, Ryan set the tone. Participants went on to elect officers: Moses Strong, Mineral Point, president; 13 vice presidents, one from each judicial district; Edwin Bryant, Madison, secretary; and H.R. Carpenter, Madison, treasurer. They named a nine-person executive committee and set up four special committees: membership, legal education, amendment to the law (to seek amendments to laws regulating bar admissions), and judicial (to hear grievances against practicing lawyers). Participants also debated and approved a constitution and bylaws, and 265 of them signed the membership roll and paid their dues. Among the first items of business, the Association appointed a committee to work with the legislature to secure a reduction in the price of the Wisconsin Reports. Participants agreed to meet again on Feb. 20 to follow up on the committees' initial work.

The members of the new State Bar Association of Wisconsin, as it was known then, accomplished much at their original meeting. "It's a classic example of intelligent people foreseeing problems and seeking to alleviate problems in an intellectual way, rather than in a confrontational way," notes Ripon attorney and former State Bar president Steven Sorenson, who researched and wrote the script for the first-meeting reenactment staged on Jan. 9, 2003. "To me, that was one of the best things about this. The intellect exuded on the table. And it cemented the idea that the supreme court and the judicial system should govern and supervise the legal system, rather than the legislature."

Initial Slow-going

After that initial burst of energy, the momentum slacked off considerably. The group did hold that designated second meeting on Feb. 20, 1878, but didn't meet again until three years later, and then not for another five years. Strong, who was president for the first 15 years, and the other officers and executive committee members weren't inclined, for whatever reason, to call regular annual meetings. Ryan died two years after the Association's founding, but his role had been to help launch the organization, not to be actively involved in it. This hands-off stance was necessary, he thought, because as chief justice, he might be called to decide upon matters the Association brought before his court.

Regular annual meetings began in 1903 and continued every year thereafter. But overall activity was low, owing, in part, to poor roads and the time- consuming nature of railroad travel and Association work - time taken away from trying to make a living practicing law. Indeed, Philip Habermann wrote in A History of the Organized Bar in Wisconsin, the Association's first 70 years "were noted only for inertia."

President Moses Strong was the first to sign the membership roll. The constitution, bylaws, and roll are bound in a leather ledger, housed at the State Historical Society, Madison.

Still, there were several noteworthy developments. The Association advocated strongly for higher bar admission standards and won improvements gradually. An 1885 law created a court-appointed board of five lawyers to examine bar applicants, who before admission had to have two years of law study, although this didn't have to be in either a law school or law office. As of 1870, University of Wisconsin Law School graduates (who didn't have to be high school graduates) gained automatic admission to the bar, an arrangement that came to be known as the "diploma privilege." This was extended to Marquette University Law School graduates in 1933. Admission standards rose in steps over many years. But it wasn't until 1940 that the supreme court required three years of college before law school and abolished law office study as a substitute for law school.

In 1900 the Legal Education Committee proposed a code of ethics for the profession and also suggested a required reading list for those who sought admission to the bar. The code gained approval at the next year's annual Association meeting. But it would be another 55 years before any mechanism was in place to effectively discipline practicing lawyers who violated the ethics code.

Another event of note in the early 20th century was a speech by president Claire Bird at the 1914 annual meeting calling for an integrated bar - that is, all lawyers practicing law in the state would be required to join the Association. Wisconsin was the first state to consider such a proposal. Bird described it as "radical and fundamental," and indeed it engendered debate that went on for decades in the legal profession, the legislature, and ultimately the supreme court.

George Morton, a Milwaukee lawyer, also surfaces as a key individual in these years. As chair of the Membership Committee in 1912 and later treasurer and secretary-treasurer, Morton gave the Association a badly needed shot in the arm. He pushed to increase membership, clean up record-keeping, and rehabilitate ailing finances. Habermann credits Morton as the person who "probably saved the inept and poorly organized association from total stagnation."

But Morton burned out after a decade. Stepping up to the plate was Gilson Glasier, who worked full time as the state law librarian. For 25 years, as a sideline to his regular job, Glasier dedicated many hours to keeping and storing Association records, a task for which he received a small stipend. In 1928 he launched the Association's first magazine, and he served as its editor until 1949.

The year 1929 brought another proposal that was to have lingering effects for decades. For one hundred years after statehood Wisconsin lawyers were inadequately compensated, wrote Habermann. In the earliest days, most law work was charged for at flat rates, court work on a daily rate; and most lawyers who became well off did so through side ventures. Most of the fault for poor compensation lay in the haphazard system of charges for service. Up until 1929, many local bar associations had schedules listing minimum fair rates for various types of law work. At the Association's 1929 meeting, debate ensued over the merits of a statewide fee schedule. It passed and was considered to be a guide, not a bible. Numerous revisions adapted it to changing times. Minimum fees had a great impact on the economics of law practice; lawyers were keenly aware of the profession's economic pitfalls and poor pay, which was made more uncertain by clients who shopped for the lowest fees. However, in 1972 the U.S. Department of Justice decreed that the fee schedule violated price-fixing restrictions in anti-trust laws. That was the end of fee schedules. Still, the concept, which endured for 43 years, signaled that lawyers were more serious than before about keeping an eye on the economics of law practice.

Meanwhile, other societal changes in the first half of the 20th century affected lawyers and the Association. The automobile, prevalent around the state by 1907, induced a spate of road building. The combination of automobiles and improved roads made it easier for lawyers to get around. Automobile accidents, new tax laws in 1903 and 1911, and the passage of the Workman's Compensation Act in 1911 brought more work through lawyers' doors. And the law profession, like the rest of the country, had to survive the Great Depression and two World Wars. World War II, in particular, sent lawyers away from Wisconsin in droves. Those who returned to their practices were accompanied by other military veterans who opted to earn law degrees under the GI Bill.

Law schools were not prepared for the influx of law students following World War II. "When I entered law school in 1947, there were twice as many students as available seats and when I graduated, I faced an employment market that was less than desirable," writes Janesville attorney George K. Steil Sr., who was State Bar president in 1977-78. Many lawyers took employment in industry until they could find an opening where their legal talents would be used. "A lawyer in my home town urged me not to come back to my home town to practice law because there were too many lawyers there," Steil recalled.

Strides were made in law office management, too, as technology that was developed during WWI and WWII for the military was adapted to civilian pursuits. For example, the advent of the electric typewriter and the copying machine, as well as systems for capturing time records, all helped to point lawyers to new ways of thinking about and managing their law practices.

The stage was set for profound changes in the Bar Association in the years ahead.

The Next Wave

The late 1940s posed new challenges and opportunities for the Association. Veteran lawyers returning after years in the war needed to refresh and update their legal skills. The lawyer ranks burgeoned rapidly with post-war law school graduates. The supreme court rejected the latest attempt in 1946 to integrate the bar, urging the Bar Association to try again to succeed as a voluntary organization. The Association was perhaps at its most significant crossroads since its founding 68 years earlier. The 1947 annual meeting in Green Bay adopted a new constitution and charted new directions. The organization's name also changed the next year, to the Wisconsin Bar Association.

The time seemed ripe to hire the first full-time staff person. Brought on board in 1948 as the new executive secretary, Phil Habermann's task was to manage and build the Bar Association. Within a few months, he and his staff of one part-time secretary, together with one file cabinet and a typewriter, moved into a three-room rented office just off the Capitol Square, at 114 W. Washington Avenue.

Habermann stumped around the state, attending local bar meetings to cement relationships and recruit members for the state organization. "A small percentage [of lawyers] were members," recalls Madison attorney Jack R. DeWitt, who was State Bar president in 1975-76. "So, the Bar was limited in what it could do for lawyers or for the public." Habermann became active in the American Bar Association to build closer relationships there as well. The organization's finances improved and better record-keeping and publishing efforts enabled more effective communications with members around the state.

Continuing legal education, although it wasn't yet called that, also got a major boost at this time. Seeds already had been planted. Back in 1878, the founders set up the Legal Education Committee, but its focus was on education to prepare to become a lawyer. Gradually, however, concerns evolved about the need for ongoing training. President Marvin Rosenberry summed up the situation in 1926: "It is thought that we have been having on our (annual meeting) programs too much general inspirational material and not enough discussion of detailed subjects, and it is suggested that it might be advisable to have a number of round table discussions on definite topics."

The solution was to offer legal clinics and regional meetings around the state. These focused on practical discussions led by panels of local attorneys. The frequency of these events dwindled during World War II, but after the war the need for educational offerings for returning military veteran lawyers spiraled. The Bar Association created a Post-Graduate Education Committee in 1947. The next year, one of the new executive secretary's main tasks was to install an active training program. Initially, this mostly took the form of numerous regional sessions around the state.

Another of Habermann's chief duties was to lobby the legislature. Up to that point, the Association struggled with its legislative activity, never seeming to figure out what its role should be. One action it did take was to launch its first legislative bulletin for members in 1927. But overall, the Association's stance on legislative matters remained reactive, rather than proactive, until Habermann became its lobbyist. Prior to his employment with the Association, Habermann had served as the first full-time director of the Legislative Council, an agency of the Wisconsin State Senate and State Assembly. Because Habermann's responsibilities there included research and coordination of the activities of the various subcommittees, he was well-acquainted with legislators, well-versed on the issues before them, and knowledgeable on how to approach them to advance the Association's interests.

Then in 1955, the Association approached yet another turning point when president Alfred E. LaFrance of Racine announced his plan to again pursue integration. The supreme court approved it the following year, although, of course, the debate over integration was far from over. Still, 1956 marked a major shift in the Wisconsin Bar Association's direction, soon to undergo restructuring and another name change, to the State Bar of Wisconsin. The story continues in the June issue.

When the State Bar of Wisconsin celebrated its 80th anniversary in January 1958, several elements were about to click into place.

- That summer the Bar moved from its rented three-room office suite near the Capitol Square into a home of its own at 402 W. Wilson Street, Madison. Owning the newly constructed building "gave us a sense of solidarity and permanency," said Eau Claire attorney and 1963-64 State Bar president Francis Wilcox in a September 1998 Wisconsin Lawyer interview.

- At the end of that year, the Wisconsin Supreme Court made Bar integration permanent, after a two-year trial period, thereby solidifying the Bar's broadened membership base.

- The above developments meant that the Bar's staff, led by executive director Phil Habermann, by then a 10-year veteran on the job, had the physical space and financial resources to expand and improve services to Bar members. Thus, the State Bar was poised to enter a new era, in which the energy and activity level would surpass anything seen in the organization's first eight decades. By the late 1950s, the Bar had hit its stride. And it's been on the move ever since.

Thus, the State Bar was poised to enter a new era, in which the energy and activity level would surpass anything seen in the organization's first eight decades. By the late 1950s, the Bar had hit its stride. And it's been on the move ever since.

New Focus on Public Service

A chance inquiry at a summer 1950 Rock County Bar dinner meeting spurred the creation of a new Bar entity. An elderly lawyer seated next to Habermann at the dinner table wondered whether there was a Bar program he could name as a beneficiary in his will. Nothing like that existed, Habermann responded, but he broached the topic with Wisconsin Supreme Court Chief Justice Marvin Rosenberry as the two men drove back to Madison that night. A foundation would be a solution, advised Rosenberry, who offered to help Habermann form one. And so, the following spring, the Wisconsin Bar Foundation (now the Wisconsin Law Foundation) came to be.

Money trickled into the Foundation, and a few lawyers signed on as members. But for years the Foundation sat inactive, as if waiting for someone to figure out exactly what to do with it. An answer arose a few years later, when the Bar drew up plans in the early 1950s to build a new headquarters. Due to its then voluntary status, the Bar couldn't own real estate or hold a mortgage, but the Foundation could. The Foundation thus struck on its first useful purpose. Once construction of the new headquarters was under way, however, the Foundation slipped into dormancy once again.

In the late 1960s, the Foundation finally found a niche that it has filled ever since. In 1969 it launched Project Inquiry, a program that sent hundreds of lawyers into classrooms across the state to discuss the law and stage mock trials. Volunteer attorneys also wrote the first edition of On Being 18, which won the American Bar Association's Silver Gavel Award. That booklet has undergone countless revisions over the years and is still in distribution today. "Phil was smart enough to see that the Foundation was a way to implement projects the Bar couldn't do," says Madison attorney and 1975-76 Bar president Jack DeWitt. "If you took dues money [to run certain programs], someone might squawk about it. But the Foundation could try out these projects because it was using donated money, not dues."

Project Inquiry was the forerunner to many current educational programs that are now operated under the Bar's auspices, including Lawyers in the Classroom, We the People, Court with Class, and the High School Mock Trial Tournament, to name a few. As Chief Justice Shirley Abrahamson points out, "Lawyers make wonderful teachers, and teaching, in turn, makes the practice of law more rewarding." The Foundation now serves as the fund-raising arm to keep these projects going. Besides law-related education, the other function the Foundation took on was public service. In 1978 it launched the Lawyer Hotline, through which volunteers answered consumers' simple legal questions over the phone or steered them to the Lawyer Referral Service if appropriate. "It was an attempt to make the system more accessible to people," says Reedsburg attorney Myron LaRowe, then chair of the Bar's Lawyer Referral Committee and later Bar president (1981-82). "We basically had one phone in the old headquarters. I'd be down there to work the phone for a few hours, and other attorneys volunteered. We staffed it that way for quite a while."

The hotline and referral services continue to exist today, both now under the umbrella of the Lawyer Referral Service, a Bar program. The LRS assistants field more than 50,000 calls each year, and volunteer attorneys still participate in various ways (see LRS).

Yet another area of public service evolving since the 1950s was the Bar's pro bono work. This got a major push in 1957 from the Bar's Legal Aid Committee chair Walter Graunke of Wausau, known in his day as Mr. Legal Aid, who rallied local bars to help people who couldn't afford legal services. The movement gained momentum in 1966, when the Bar won a federal grant to create Judicare. The Bar developed an innovative service model it felt would best serve people in a predominantly rural state, despite wrangling with the federal government over structure. Other state bars took note of Wisconsin's approach and sought funds to replicate it in their states.

Eventually, the Bar spun off Judicare as a separate nonprofit corporation, and it, like the other legal aid services established in the state in the 1970s, has continued to struggle with Washington to win sufficient funding to adequately serve low-income people. As La Crosse attorney and 1992-93 State Bar president Tom Sleik observes, "Some politicians love to talk about the rule of law, but what does the rule of law mean to somebody who's excluded from it?"

Sleik made pro bono services one of his top priorities during his tenure as president. For the first time, the Bar hired a full-time pro bono coordinator to coordinate efforts statewide. That way lawyers could devote whatever time they could give to actually providing pro bono services to clients, rather than to the administrative side of it. "That was the idea behind hiring a coordinator," Sleik points out. "How could we organize the delivery of legal services to those who weren't getting them? It's unrealistic to expect that lawyers who are already very busy are going to find the time to make this happen."

The Bar's Team Pro Bono program, which has had a full-time coordinator ever since 1993, makes it easier for interested lawyers to get involved (see Team Pro Bono)."It's one of the most positive things we've ever done," Sleik says, "to persuade the public that we really do care."

Professional Excellence

Advancing lawyer competency and integrity has been a Bar goal from the outset, as evidenced by founder Edward G. Ryan's speech advocating the expulsion of the "knaves and fools" from the lawyer community in order to preserve the profession's reputation and protect the public. Toward that end, professional education and ethics long have been priorities.

Education took major strides forward once Habermann came on board as a full-time executive in 1948. "Before Phil became executive secretary," DeWitt recalls, "they'd have a lawyer or two speak on various subjects at the annual Bar meeting. Typically it was a war story, and [the presenter] might distribute 50 to 75 mimeographed copies of handouts."

As membership numbers exploded upon Bar integration in 1957 and law practice grew ever more complex, demands for training grew. By the early 1960s, the Bar, the University of Wisconsin Law School, and Marquette University Law School all had training programs for practicing attorneys. In 1962 Bar officers and the two law schools' deans met to discuss the future of post-graduate legal education and how they might coordinate their efforts. From that discussion arose the Institute for Continuing Legal Education for Wisconsin, or CLEW, in 1963. This new entity, staffed and housed at the U.W. Extension Law Department, presented institutes and clinics on diverse topics. Meanwhile, the State Bar continued to hold a few clinics of its own, as well as the usual annual and midwinter meetings and the popular annual tax school.

James Ghiardi, now an emeritus professor at Marquette University Law School, was on the Bar's Executive Committee when the law schools and the Bar pooled CLE efforts. By 1969, when John Wickhem was Bar president and Ghiardi was president-elect, the three entities' interests "had started to drift apart," Ghiardi says. "We talked about it in the Executive Committee, and the question was, why don't we do this on our own?" The decision to do so gave birth to the Advanced Training Seminars, commonly known as ATS-CLE, the forerunner to today's CLE program. Dalton Menhall managed ATS-CLE, along with Habermann, and then in 1974 Menhall became the program's first full-time director.

Still, room remained for improvements. "When I worked for the Judicial Council," DeWitt recalls, "I spent a lot of time talking to judges and lawyers all around the state. I knew there were many lawyers who didn't realize the statutes had changed in the 40 years since they'd been to law school. The problems they created and the mistakes they made might not show up until 15 to 20 years later."

Talk began to circulate nationwide, and in Wisconsin, about the wisdom of mandatory CLE for lawyers. A Bar committee submitted a plan to the supreme court in 1975, which in turn ordered the Bar to put the issue before its membership in a referendum. DeWitt, at that time Bar president, was among those who lobbied hard for passage. "We knew it was controversial," he says. "We tried to get lawyers to see the value of it. I told them they had to think about the kind of service the public was getting." The referendum passed, with nearly 72 percent of voting members voting in favor of mandatory CLE, which became effective Jan. 1, 1977.

The CLE program headed in another new direction in the early 1980s with the expansion of CLE books. By this time, the days of the mimeographed handouts were long gone, and seminar handouts had become more substantial. These eventually evolved into books, whether as seminar companions or stand-alone resources. "They were excellent products," notes Madison attorney Carolyn Lazar Butler, who ran the CLE book department from 1984 to 1999. "But they were not kept up-to-date or supplemented on a regular basis. And they were not cite checked and had no indexes."

Butler's task was to remedy these shortcomings and to create quality publications that would prove useful for everyone from newly graduated lawyers to seasoned practitioners. The endeavor also was required to pay its own way, requiring no Bar dues to function. It was a program the likes of which existed at the time in only a few states with larger bars. "Gary Wilbert [then CLE director] was the force behind this," Butler points out. "He said, 'We're not a big state, but I bet we could do a really good job for lawyers.'"

Coupled with the expansion of CLE since the 1950s has been a growing emphasis on professional ethics and discipline. The Bar adopted its first ethics code in 1901, but no genuine enforcement clout existed until the supreme court issued its order integrating the Bar in 1956. Court rules created new district grievance committees to investigate complaints against attorneys and recommend action to the State Board of Bar Commissioners. The latter operated under the State Bar's auspices until 1977. Then, mirroring a national trend, the supreme court transferred responsibility for grievance investigations to a new, separate agency, the Board of Attorneys Professional Responsibility, now the Office of Lawyer Regulation.

Meanwhile, in the last century, the ethics code has undergone numerous transformations as society and law practice have changed. Now the current Wisconsin Rules of Professional Conduct for Attorneys, in effect since 1988, are being revisited in light of recent changes in the ABA's Model Rules. "There is a continuing need to center on and update our rules in order to properly self-regulate our profession," says Wausau attorney Dean Dietrich, a member of the Wisconsin Ethics 2000 Committee, which is studying possible rule changes and will report to the supreme court by October 2004.

"In the founders' time," Dietrich adds, "certainly lawyers were important to society. The continued emphasis on ethics and professional responsibility is designed to make sure we continue to focus on the public trust and confidence vested in us."

Integration, Agitation, Legislation

After Bar president Claire Bird of Wausau first proposed Bar integration in 1914 as a way to improve professional standards and discipline, rounds of debate over the issue ensued for decades. The supreme court finally settled the issue, or so it thought, in 1956, when it adopted the Rules of Integration, effective Jan. 1, 1957, for a trial period of two years. By mid-1957, after a six-month enrollment flurry, membership had grown by 24 percent, from 4,968 to 6,174.

Fifteen State Bar presidents gathered at the 2003 Annual Convention in Milwaukee to celebrate the Bar's 125th anniversary. Front row, from left: Gerald Mowris (2001-02), James D. Ghiardi (1970-71), Susan R. Steingass (1998-99), Truman Q. McNulty (1978-79), Patricia K. Ballman (2002-03), Thomas J. Curran (1972-73), Pamela E. Barker (1993-94). Back row, from left: Jack R. DeWitt (1975-76), George Burnett (2003-04), Gerald M. O'Brien (1987-88), John R. Decker (1990-91), Steven R. Sorenson (1997-98), Franklyn M. Gimbel (1986-87), Patrick T. Sheedy (1974-75), Donald L. Heaney (1985-86). Not pictured: Gary L. Bakke (2000-01), John S. Skilton (1995-96), Gary E. Sherman (1994-95), Thomas S. Sleik (1992-93), Daniel W. Hildebrand (1991-92), G. Lane Ware (1989-90), John Walsh (1988-89), Gregory B. Conway (1984-85), Adrian P. Schoone (1983-84), Myron E. LaRowe (1981-82), Lawrence J. Bugge (1980-81), Richard E. Sommer (1979-80), George K. Steil (1977-78), Rodney O. Kittelsen (1976-77).

But the debate over integration was far from over. In 1959 Madison attorney Trayton Lathrop sued the Bar, claiming that compulsory dues were unconstitutional. Lathrop v. Donohue (Joseph Donohue of Fond du Lac was Bar treasurer at the time) went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld integration in 1961.

A second challenge surfaced in 1976, when the state supreme court appointed a committee, headed by judge Andrew Parnell, to study integration's pros and cons. The Parnell Committee recommended and the court approved continued integration the next year.

Then in 1979, integration opponents conducted a poll, finding that 60 percent of Bar members opposed integration. With that ammunition in hand, opponents petitioned the court to end integration. The court refused, but did promise close scrutiny of Bar activities, especially its legislative activities. In 1982, the court left integration intact, but it demanded that LAWPAC, a political action committee, be completely separate from the Bar, with no Bar participation whatsoever. That marked the end of LAWPAC.

On to the next round. Challengers, led by Madison attorney Steve Levine, rallied again in 1986, this time resulting in the 1988 decision Levine v. Supreme Court of Wisconsin, in which federal judge Barbara Crabb ruled that integration violated the First Amendment. The Bar appealed, with a team of attorneys from the Madison office of Foley & Lardner representing the Bar pro bono in the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. "The Bar felt, in the end," notes John Skilton, who led the Bar's legal team, "that despite the costs and the angst of being challenged, that nevertheless the benefits of having a unified bar outweighed both the detriments of litigation and of not having an integrated bar." The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals reversed Crabb's decision.

That case, too, seemed destined for the U.S. Supreme Court. But the Court denied Levine's petition, opting instead to hear Keller v. State Bar of California, which involved similar issues. In that case, the Court ruled that an integrated bar could use mandatory dues to fund activities that were germane to the goals of regulating the legal profession and providing legal services, but not activities of an "ideologic nature which fall outside these areas of activity."

The Wisconsin Supreme Court had suspended the enforcement of its mandatory membership rule in 1988 after the Crabb ruling, effectively returning the Bar to a voluntary basis, which ultimately lasted for four years. During that time, the Bar tried to sustain member programs, plus, notes Wausau attorney Lane Ware, 1989-90 Bar president, "We had to spend time convincing attorneys why it was important to be members of the organized Bar. We had a whole new realm of communication that we didn't have before."

After the Keller decision, it was back to the drawing board on the integration decision. In 1990, the Bar set up two study committees to make their case for a voluntary or integrated Bar to the Board of Governors and the membership. Following months of study, the meeting at which the Board was to decide the issue went on for hours, recalls Tom Sleik. "I can still remember the debate," he says. "It was probably one of the most thoughtful, serious debates I've ever heard the Board engage in. ... There was much respect given to both sides."

Fortunately, perhaps, for the sanity of everyone sitting through the marathon meeting, there was also a "moment of levity in the discussion that I'll always remember," Sleik recalls, even though it was at his and Dean Dietrich's expense. Dietrich commented that he had a strong gut feeling about what was the right thing to do. Sleik stood up to say he had that same gut feeling and that coming from the two of them, it ought to be extra persuasive. "You're talking about a couple of boys who at that time weighed in at a good 250 pounds apiece," Sleik says. "The joke was that, gee, if Dean and Tom have this gut feeling, it's not to be ignored."

In the end, the Board voted to recommend Bar integration to the state supreme court, which in turn approved it in 1992. The integrated Bar was back and has remained uncontested since. Certainly, all the legal challenges over the decades consumed Bar time and resources. But perhaps they were necessary, Skilton observes. "My view is that the Bar had to confront and properly deal with the constitutional issues inherent in a decision to mandate membership," he says. "So whether it was good in the sense of policy, it was good for the Bar. It was like taking medicine."

Still, even with the Keller decision, or perhaps because of it, the Bar's role in legislative activity remains a controversial activity, notes George Brown, a former Bar lobbyist and now its executive director. Lawyers hold varying opinions on what constitutes "germane" legislative activity. "When you get 21,000 intelligent, generally strong-willed individuals involved," Brown points out, "you're going to have dissension out there. That's why we have the rebate option."

The latter, commonly known as the "Keller rebate," allows members to deduct the portion of their dues that pays for the Bar's legislative activity. A Bar committee devised rules and procedures for setting rebate amounts and arbitrating disputes, which the supreme court approved. Port Wing attorney and 1994-95 Bar president Gary Sherman, a member of that committee, notes that bars across the country reacted differently to Keller. "Some bars felt they had to get out of the business of political activity altogether," he says. "Some went to the other extreme and almost ignored Keller in how they did dues rebates. We thought we were right on the money in both the letter and spirit of the Keller decision." That position, and the rebate process, have been borne out, he adds, by the dearth of complaints about rebate amounts ever since.

Over the decades, the Bar and its sections have been major forces in helping to shape laws in marital property, family law, corporate law, product liability, and many other areas of public interest. "The benefit to the Legislature," Brown says, "is lawyers' knowledge and experience. The Bar can go to the Legislature and say, 'If you want to make this work, here's a better way.' We do that sometimes. Other times we actually take a position on policy."

One legislative matter struck close to the Bar's heart in 1977. A group of legislators attempted to shift control of lawyers from the courts to the Legislature - precisely the situation founder Ryan had adamantly opposed 99 years earlier. Lawyers would then be vulnerable to politics, Ryan had argued, rather than subject to the rule of law. "I'm sure he would have cringed that this was even suggested," observes Janesville attorney George Steil, 1977-78 Bar president.

But on Friday, Sept. 23, 1977, Bar lobbyist Edgar Lien reported at a Board of Governors meeting that the bill's supporters had the numbers. And the vote was only three days away. Steil recalls a rapid mobilization. "Everyone was assigned to contact legislators over the weekend," he says. "The Bar got into action. And that was the end of it." The Legislature defeated the measure, which to date hasn't resurfaced.

A Rising National Reputation

The State Bar of Wisconsin has made a name for itself nationwide through its track record of devising creative ways of meeting lawyers' changing needs. A case in point is the founding of the Wisconsin Lawyers Mutual Insurance Company (WILMIC) in 1986.

The advent of the 1980s brought a growing malpractice insurance crisis. "Premiums were going out of sight," LaRowe recalls. "The coverage was shrinking. The number of insurance carriers providing coverage was shrinking. You could see the handwriting on the wall." The situation worsened by 1986, and the Bar's Insurance for Members Committee struck on the idea of forming the Bar's own insurance company. The committee put the legal paperwork in motion. A massive campaign swung into gear to raise the necessary $3 million to capitalize WILMIC to the level required by the state's Insurance Department. Law firms and individual lawyers across the state bought bonds at $1,000 apiece. And WILMIC materialized.

Since its founding, WILMIC has had to endure softer market cycles when other insurance carriers resurfaced, eager to offer Wisconsin lawyers malpractice coverage and slashing rates to compete. "WILMIC hung in there through that," says Steve Smay, Bar executive director from 1978 to 1999. "The idea was that the next time there would be a hard insurance market, WILMIC would be there."

Bar members ran WILMIC themselves for the first several years. By the time Lane Ware became Bar president in 1989, the need for professional insurance management was clear. WILMIC converted from a volunteer lawyer-run association to an organization operated by insurance professionals. Ware views WILMIC's evolution as just one example of the Bar's growing maturity in recent decades. "There was a crisis," he says. "The Bar saw it, formed a task force, created the company, funded it through contributions. And then, when the time was right, we stepped away."

Fast forward a decade to another challenge: the impact of technology on legal research. Lawyers were shifting from case law research in printed digests toward electronic sources, at that time in CD-ROM format. But the old case citation system tied to books and page numbers didn't fit well with electronic sources. After several years of study in the early 1990s, the Bar's Technology Resource Committee devised a new system of case citation that would be medium-neutral, involving numbering paragraphs, rather than pages. "When we went before the [state] supreme court to argue for the new citation system," Sherman recalls, "we were leading the entire United States in dealing with this issue." The Bar also faced legal challenges from West Publishing, but in the end the Bar prevailed. And the new case citation system caught on nationally.

Another project aimed to help lawyers conduct their legal research more efficiently. The Bar envisioned a CD-ROM source that would include Bar publications and links within those publications to primary sources. The Bar sought proposals from four vendors, one of which was a start-up company called Law Office Information Systems (LOIS). "We had demands," Sherman says, "and nobody was willing to meet all of them as well as LOIS was. They were new, and they were taking a risk."

Through the joint venture, the first of its kind in the country, the Bar got the research tool it wanted for members. And, compared to competitors' products, it also came with a much smaller price tag. That ultimately drove competitors' prices down, making electronic legal research generally more affordable.

Looking back on those years in the mid-1990s, Sherman describes them as "a time when a lot of things came together. A lot of extremely creative people put a tremendous amount of energy into [these projects]. I think you can't give enough credit to the leadership of [Bar executive director] Steve Smay."

Smay now works for LOIS and travels to bar associations across the country. He knows firsthand the solid reputation the Bar enjoys outside its home state. "The number of people I meet," he says, "who know what the Wisconsin Bar has done - and is still doing - is just amazing."

Changing Faces

The Bar, of course, is more than programs; it's also the thousands of individuals who comprise it. These days that group is much more varied than it was 125 years ago, or 50 years ago, or even in more recent times. "What strikes me is the increased role of women in the Bar," says Joseph Ranney, a Madison attorney and legal historian and author. "The presence of women in the Bar was minuscule until about 1970, and then it exploded. It's interesting to see how the role of women in the Bar goes hand-in-hand with the historical phases of the women's movement."

The women's movement of the 1970s followed on the heels of the civil rights movement of the 1960s, just as the first push for women's rights sprang up after the abolition of slavery a century earlier. Lavinia Goodell, a Janesville attorney, was the first woman to attempt to gain admittance to practice before the state supreme court in 1875. The court denied her application, with Chief Justice Ryan stating, "There are many employments in life not unfit for female character. The practice of law is surely not one of these. ... Womanhood is moulded for gentler and better things." Goodell finally won admittance to practice before the supreme court in 1879, over Ryan's objection.

Today, women make up 28 percent of the State Bar and 50 percent of Wisconsin law schools' classes. The Bar has had three women presidents - Milwaukee attorney Pam Barker, 1993-94, Madison attorney Susan Steingass, 1998-99, and Milwaukee attorney Pat Ballman, 2002-03, and a fourth - Madison attorney Michelle Behnke - will take office in 2004. Plus, the state has many female judges, and soon four of the seven seats on the state supreme court will be held by women. Certainly, Ryan would be aghast at such developments, but, as Chief Justice Abrahamson recently noted, "Lavinia Goodell, I am sure, is beaming."

The racial and ethnic composition of the Bar also has diversified dramatically in recent decades. Here "firsts" are more difficult to document because the Bar has not kept racial or ethnic data on its members. One first, however, is extremely recent history. In April, Michelle Behnke became the Bar's first African-American president-elect; she will take office as president on July 1, 2004.

Expanding diversity in the Bar now stands as a key objective, as exemplified by one of the Bar's stated values: We will be inclusive. "Diversity is not about just race and gender," notes Pat Ballman, Bar president. "It goes beyond that to cover all kinds of differences - age, geography, cultural backgrounds."

Diversity also is more than a question of political correctness. In the broader picture, Ballman says, justice will be better served if there are more lawyers and judges who look like and understand the cultural backgrounds of the people going through the justice system.

As for the Bar association itself, diversity has practical advantages, Ballman points out. "People with varied backgrounds bring different creativities to the table and different solutions to problems. We need to look at that as an asset to the Bar."

Thus, 125 years after its founding, the Bar continues to serve one of its original purposes: to advance the profession and legal services by speaking "with one voice," as Ryan put it. But today, that voice is - or is at least striving to be - a richer blend than ever before in the Bar's history.