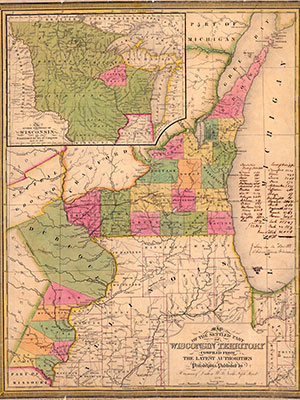

Photo: A color map of the settled part of Wisconsin Territory, including an inset map of the “Entire Territory of Wisconsin as Established by Act of Congress, April 10, 1836.” Wisconsin Historical Society, Creator Unknown, Map of Wisconsin Territory, Image 108049, viewed online at https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM108049. Reprinted with permission.

The arc of the origin story of “Wisconsin” bends over seven decades, with various fits and starts along the way, before inhabitants, many of European ancestry, finally secured statehood in 1848. Essentially, the creation of the 30th state rested on six legal pillars: an ordinance, a territorial petition, a voter-approved statehood referendum, an enabling act, a voter-approved constitution, and Congressional ratification for admission.

The land that would become Wisconsin was included as part of the “western territories” governed under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 (hereinafter the Ordinance).1 The Ordinance arose from and was passed by the Confederation Congress after a four-year debate about the United States’ westward expansion and governance of the territories north of the Ohio River.

The Ordinance addressed, and even dictated resolutions to, the thorniest questions debated at the time; questions that rattled the politicians and businessmen into calling for the 1787 Constitutional Convention. In fact, the eventually adopted U.S. Constitution echoes the Ordinance’s insights and innovations.

Question 1: How would the ambition for land ownership, settlement, and growth of the nation be curbed and controlled? The Ordinance introduced the revolutionary concept of “public domain” land; that is, under the Ordinance all unsettled land was ceded to the Confederation Congress, which would be temporary administrator until new states emerged from the western territories via a detailed ratification process. The Confederation’s 13 original states would not be allowed merely to expand their holdings, boundaries, or power. In fact, the Ordinance required that seven of the original 13 Confederation states relinquish any respective claims they had staked in the western territories.

Question 2: How were the states to be created and treated? The Ordinance designed a system of prerequisites for establishing territorial governments; it set the standards for admission of a new state through a Congressional enabling act. Most important, any newly admitted state would be treated equally – as to other newly admitted states and as to the existing states included in the Confederation Congress.

Questions 3 and 4: What rights were the territorial inhabitants granted, and would slavery be allowed? Territorial inhabitants were granted public education set-asides and were guaranteed both civil and religious liberties and the prohibition of slavery in the territory.2

As the western territory boundaries were redrawn by newly established states, governance of the remaining land claims was assumed by the territorial governments.3 Therefore, the yet-to-be-defined “Wisconsin” was embedded successively with the territories of Indiana (1800), Illinois (1809), and Michigan (1818) and was subject to the laws of the respective territorial governments.

Hannah C. Dugan, U.W. 1987, is a Milwaukee County Circuit Court judge. She is a Fellow of the Wisconsin Law Foundation.

Hannah C. Dugan, U.W. 1987, is a Milwaukee County Circuit Court judge. She is a Fellow of the Wisconsin Law Foundation.

Forty-nine years after the Ordinance’s effective date, the region to be known as Wisconsin reached a population of more than 10,000 non-indigenous persons, and therefore became eligible to become its own territory. In 1836, the Michigan territorial governor petitioned for the creation of the Wisconsin Territory. James Duane Doty, who invested in Wisconsin land and was a representative in the Michigan legislature, led the campaign to create the Wisconsin Territory.

During April 1836, the U.S. Congress debated the boundaries, infrastructure, and funds for the proposed Wisconsin Territory. The Congressional resolution passed and was approved by President Andrew Jackson on April 20, 1836, with an effective date of July 3, 1836. President Jackson’s gubernatorial appointment of Henry Dodge and his other territorial officials’ appointments began on July 4, 1836.4 When the initial territorial legislature convened, it conducted a formal census, in August 1836, and identified more than 11,600 residents who were not Native Americans.5 Three months later, elections were held, and the newly elected delegates convened at Belmont.6 An early priority was the highly political and controversial selection of the site for the territorial capital. Critical to the new territory’s status, Governor Dodge appointed a non-voting, territorial delegate to his seat in Congress.

The territorial government oversaw further ceding or takeover of additional tribal lands, the required preparation of U.S. government surveys, public infrastructure improvements, and a tremendous influx of settlers – most of them European immigrants.

Ten years passed.

Four states had emerged from the western territories, subject to and created by the Ordinance’s strictures. Wisconsin was the last to establish a territorial government and to vote for statehood.7 Despite reaching a population of more than 155,000 (far exceeding the minimum 60,000-person population required to seek statehood), Wisconsin Territory settlers denied themselves self-governance and statehood by voting down statehood referenda three times – in 1842, 1843, and 1845.8

In 1846, the Wisconsin Territory settlers finally voted “yes” on the referendum seeking statehood. Bolstered by the will of the voters, Wisconsin Territory Congressional Delegate Morgan L. Martin traveled from Green Bay to Washington, D.C., to campaign for seeking Congressional passage of an enabling act – authorizing the Wisconsin Territory inhabitants to adopt a state constitution and to form a state government. He arrived to a federal government distracted by a host of crises. Nevertheless, through his singular diligence and determination, Martin secured the necessary votes; Wisconsin moved another step forward toward statehood.

Resource Information

Arthur J. Dodge, Wisconsin’s Admission as a State: The History of the Enabling and Admission Acts in the XXIXth and XXXth Congresses (Milwaukee Sentinel & St. Paul Pioneer Press 1898).

Library of Congress, Primary Documents in American History: Northwest Ordinance, www.loc.gov/rr/program//bib/ourdocs/northwest.html (last visited May 18, 2023).

Some Legacies of the Ordinance of 1787, https://loc.getarchive.net/media/some-legacies-of-the-ordinance-of-1787-d237c9 (last visited May 18, 2023).

Mark Wyman, The Wisconsin Frontier (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1998).

Alice E. Smith, The History of Wisconsin: From Exploration to Statehood, Volume 1 (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 1973).

Milo M. Quaife & Joseph Schafer, The Attainment of Statehood (Madison: State Historical Society, 1928).

Endnotes

1 British holdings of the region were yielded to the Confederation Congress pursuant to the 1783 Treaty of Paris. However, the region’s uncontrolled occupation by eager European, colonial, and American settlers coupled with the prior settlement against and confrontations with the indigenous peoples’ interests, led to a variety of Confederation Congress acts to control the settlement, commerce, and orderly growth of the western territories. By 1787, land of indigenous people, tribes, and nations had been “ceded” by treaty, sold, or taken, largely by the confederation government, and the states of Virginia and Massachusetts, respectively. The Ordinance references indigenous people and nations in two of its sections but not regarding land claims.

2 The language of the Ordinance’s Article Six, prohibit slavery, is markedly similar to the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

3 An important provision of the Ordinance is the survey of public lands, an enormous effort that measured and controlled the land for sizing, ownership, and sale and pricing of the western territories’ claims. This tremendously significant provision reportedly was coauthored by Nathan Dane, for whom Dane County was named.

4 United States. Congress. The Congressional Globe, Vol. 2-3: Twenty-Fourth Congress, First Session, book, 1836; Washington D.C. (https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc30905/; accessed May 26, 2023). Univ. of North Texas Libraries, https://digital.library.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Government Documents Dept.

5 The Wisconsin Territory 1836 census recorded more than 11,600 white residents, most of whom lived in Iowa County (the designated mining region of the time), followed by Crawford County (which included the military fort in Prairie du Chien), Brown County (which included the oldest port and occupied city of Green Bay and the military personnel posted at Fort Howard), and Milwaukee County (which included the port city of Milwaukee).

6 The Ordinance specified that the Territorial Legislature consist of one representative for every 500 white males over 21 years of age.

7 Ohio (1803), Indiana (1816), Illinois (1818), and Michigan (1837). A small part of the western territories became a part of Minnesota upon its statehood in 1858.

8 The only persons with suffrage for each of the referenda were white males who were at least 21 years old.

» Cite this article: 96 Wis. Law. 39-41 (June 2023).