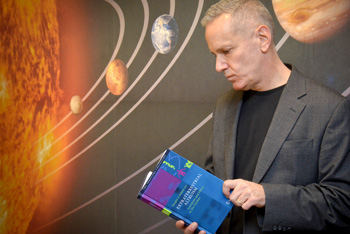

Adam Korbitz operates CeleJure Consulting, Madison. Photos: Amber Barnes, Rose Photography.

What have you been up to lately?

Writing, mostly, about science policy, particularly regarding issues of risk analysis in relation to new and emerging technologies and the law. I am also very interested in space law, which is a growing field in part because of the new private space industry that has developed in recent years.

How did you get interested in science policy?

It has been a life-long process. I have always loved science, especially astronomy and other space sciences. But I lacked a passion for math when I was in school. So I became a lawyer. I ended up spending the better part of 20 years after law school working in Wisconsin politics, or rather around and with politicians, in particular the state legislature and the Wisconsin Supreme Court. At various times I worked for a Republican, a Democrat, and at a couple of nonpartisan organizations, including the State Bar of Wisconsin. I always found the policy issues far more interesting than the politics, especially when the policy issues touched on science or technology.

Tell us more about some of your recent writing projects.

Two chapters I wrote for an academic book published this fall by Springer involving policy issues related to the scientific “search for extraterrestrial intelligence” (SETI). I am also working on two related book proposals, and in December I submitted an academic journal article based on a few lectures I gave in 2012, one at a NASA astrobiology conference and another at an international SETI symposium in the Republic of San Marino, near Italy.

Searching for extraterrestrial intelligence? That sounds very … far-out!

It is, and I love the subject. My wife and I were on vacation in Paris in 2008 at the same time there was a small SETI symposium at the UNESCO headquarters there. On a whim I decided to attend, not fully realizing it was a working conference of the top scientists in the field. Here we all were, crammed into a tiny room no larger than a typical classroom, for four days. I sat in the back row, directly behind the scientist who was the real-life inspiration for the character played by Jodie Foster in the 1996 movie Contact, based on the novel by the late Carl Sagan; Sagan and the scientist were friends.

I was the only lawyer there, and one of the few non-academics. It was intimidating at first, but I was hooked. Two years later, I was presenting my own papers at a similar but larger conference in Prague, and later at one hosted by the Royal Society in Britain. These are brilliant, fascinating people engaged in science that sounds like science fiction, but is not. Intellectually, it is exhilarating.

What can a lawyer contribute to a scientific field as esoteric as SETI?

The field is laden with intriguing policy issues. For example, there is a controversy among scientists within the SETI field as to whether it might be dangerous for us to broadcast radio messages to planetary systems around other stars in our galaxy that might contain intelligent civilizations, an experiment called “Active SETI” to distinguish it from traditional, passive SETI experiments that only listen for signals. Some scientists are already engaging in Active SETI in hopes of one day receiving a reply, but others – including physicist Stephen Hawking – have opined Active SETI might be dangerous and some even think we should consider outlawing this practice. There are other issues, too, which have legal implications: Who gets to decide who speaks for Earth? Is Active SETI free expression under national and international law, or is it akin to shouting “fire” in a crowded theater?

According to its critics, how might Active SETI be dangerous?

It is widely accepted by scientists that if another technological civilization currently exists in our corner of the Milky Way, it is likely far older and much more advanced than we are – the reasons for this assumption are complicated but are basically statistical. Those who have opposed the early Active SETI experiments are concerned they could alert an advanced civilization to our existence, and they argue that we don’t know what it might do. The problem I have with that reasoning is that it makes many assumptions for which we currently have absolutely no evidence, beginning with the assumption that we are not in fact alone. Until we have the evidence, for all we know we are broadcasting to an empty sky. That’s the basic purpose of science, to discover the unknown. We should not curtail science based on fear and nothing more. That’s circular, and it leads nowhere.

But others think Active SETI is a risk worth taking. Why?

Throughout recorded history, people have looked to the sky and wondered if we are alone. Scientists may finally have the answer within our grasp, perhaps within our lifetime. It’s a basic existential question. Thousands of confirmed and potential planets have been discovered in our galaxy over the last 20 years through projects like the recently concluded Kepler telescope mission; we don’t yet know if any of these planets are home to life, whether that life be microbial or intelligent. For all we know, humans are the only technological civilization in the entire universe, although there may be good reason to doubt that, we just don’t know yet. But it strikes me as absurd to suggest outlawing a scientific effort not because of what we know, but because of what we don’t know. Politically and scientifically, I think it would be an extremely dangerous precedent to set. If we had followed that reasoning throughout history, we’d still be living in caves, afraid of every shadow and sound.

Adam Korbitz visits UW Space Place, located in the Villager Mall, Madison. Space Place is the education and public outreach center of the UW-Madison Astronomy Department.

Does this controversy have wider implications?

I think it could, and that’s where I see the danger. There is a well-established field called risk communication and perception that studies, among other things, how irrational humans can be when assessing risk, especially regarding science and technology.

Can you give us an example outside of SETI?

For instance, in contrast to the United States, much of Europe has virtually banned genetically modified organisms (GMO) in agriculture based on a regulatory rationale called the precautionary principle, the same line of reasoning that is so often invoked against Active SETI. The precautionary principle essentially outlaws something unless it can be proven to be “not dangerous,” which is both foolish as well as logically impossible. Every choice we face poses risks. The question is, do we have a factual basis for correctly choosing which risks to tolerate and which to regulate? If we do not, we are deluding ourselves by believing we are making ourselves safer by choosing one course of action over another.

It sounds like you are questioning the old adage, “Better safe than sorry.”

No, not actually. Cass Sunstein, a law professor who was President Barack Obama’s regulatory czar during his first term, has done a lot of work on the precautionary principle and risk analysis, and I’ve been trying to apply some of his work to the Active SETI controversy. Sunstein has pointed out that “better safe than sorry” is more or less common sense.

The problem comes when we have no reliable data or evidence to support our choices (as in the Active SETI controversy), or when we act contrary to the data we do have because of fallacies or ingrained psychological prejudices. For instance, scientists years ago developed a form of GMO rice called Golden Rice that could effectively wipe out Vitamin A deficiency in much of the developing world, potentially saving millions of lives every year and saving millions more people from childhood blindness.

Yet today, Golden Rice – like many GMO foods – is effectively banned because of the political lobbying of anti-GMO organizations. It has nothing to do with the safety of the food. There’s no evidence it is not safe. In this way, the anti-GMO movement is very similar to the anti-vaccine movement, and similarly anti-science. This is horribly tragic, and we need to keep similar fallacious reasoning from negatively affecting other areas of science and policy.