We all know what it feels like to be stuck in a traffic jam, to wait in a long line, or to be put on hold while trying to resolve a customer-service problem. The delay can seem to take forever. No matter how frustrating, these are still merely inconveniences.

We all know what it feels like to be stuck in a traffic jam, to wait in a long line, or to be put on hold while trying to resolve a customer-service problem. The delay can seem to take forever. No matter how frustrating, these are still merely inconveniences.

But what happens when delays affect an individual’s ability to resolve a dispute or get legal protection from a dangerous situation? What happens when businesses can’t get their cases heard in a timely manner? As a result of budget cuts in recent years, courts around the country have had to make difficult decisions, and not without consequences.

If we look at recent experiences of other state court systems, we see what can happen if the judicial branch is underfunded. Is Wisconsin going to end up in the same situation? There are signs the answer is yes.

The effects of these cuts can be difficult to measure, let alone to explain to people who may not understand how the court system functions or how it is funded.

The American Bar Association (ABA) Task Force on Preservation of the Justice System,1 which held public hearings around the country, has identified four crucial areas that can be adversely affected when courts are underfunded: public safety, the economy, the protection of people who need it most, and our system of government itself.

Public Safety

In its report, “Crisis in the Courts: Defining the Problem,”2 the task force found that some states have experienced delays in criminal cases to the point at which judges and prosecutors are faced with a highly unfortunate dilemma: “warehousing untried defendants in local jails at additional expense, or releasing potentially violent offenders because lengthier pretrial detention may be unconstitutional or practically impossible.”

A. John Voelker has served as the Director of State Courts in Wisconsin since 2003. He has been employed by the Wisconsin court system in a variety of positions since 1992. Before then, he worked for the Wisconsin Legislative Audit Bureau. He is a member of the Conference of State Court Administrators (COSCA) and has participated on a range of its committees. He was awarded the UW-Oshkosh Distinguished Alumni Award in 2008.

A. John Voelker has served as the Director of State Courts in Wisconsin since 2003. He has been employed by the Wisconsin court system in a variety of positions since 1992. Before then, he worked for the Wisconsin Legislative Audit Bureau. He is a member of the Conference of State Court Administrators (COSCA) and has participated on a range of its committees. He was awarded the UW-Oshkosh Distinguished Alumni Award in 2008.

For example, in Washington state, an attorney testified during a 2011 ABA hearing on court funding that a defendant in a criminal case was released as a result of speedy trial concerns, only to sexually assault a woman. In that example, a pedestrian also was killed in an ensuing high-speed chase.3

This is a specific case, but sometimes, the consequences are less obvious and more systemic: Courts in some parts of New Hampshire put a moratorium on civil jury trials as a result of budget cuts; New York began ending court proceedings promptly at 4:30 p.m. to avoid overtime costs; Massachusetts lost more than 1,100 trial court employees through attrition in an effort to save money; California laid off 350 workers, closed 56 courtrooms, and eliminated a juvenile court program in an effort to save $30 million. Lines at courts in Sacramento grew so long at one point that people brought in lawn chairs.

Thankfully, in Wisconsin we have not reached this point. But if you look at the current funding structure, and the trends related to it, we may be headed for similar difficulties. The effects will be seen in counties and courthouses throughout the state.

In the Milwaukee County Circuit Court, for example, Chief Judge Jeffrey A. Kremers indicates that all types of procedures could end up on a longer time line, potentially affecting public safety. Dates to hear restraining orders or de novo reviews could be pushed back; custody, visitation, and divorce cases could take longer; and people could be held in jail longer awaiting bail-review hearings.

What would this mean in personal terms? Kremers offers a few examples:

Trials of all types, including domestic violence and sexual assault, are delayed or have to be adjourned due to a lack of resources to hear them. Victims and witnesses would have to come back. Each time a domestic violence case is adjourned, it makes it less likely that the victim will return, which would mean the case would be dismissed.

A battered woman seeking the protection of a restraining order files a petition but cannot get on the calendar for several weeks.

A person is arrested but cannot get a bail hearing for several days and is held in jail longer than necessary.

Protecting People

Another crucial area of concern identified by the ABA task force is the protection of people who need it the most. The same economic difficulties that have led to reduced funding for the courts in many states also have increased the number of people who need timely resolution of their cases.

Reduced hours and staff can result in delays for families involved in unemployment, foreclosure, divorce, and child support cases. The rights of minorities may be infringed if the courts cannot promptly address actions filed to enforce state antidiscrimination laws.

At the same time, low-income people have fewer places to turn for assistance due to cuts in legal aid. This problem can compound itself as judges and court staff need more time to address people who end up attempting to represent themselves in court but do not understand the legal system.

What effect would these delays have on people?

Kremers notes that when a child in need of protection or services (CHIPS) case is delayed, a child may sit in a foster home longer than he or she should. Another result could be that a person who is being evicted cannot get a timely hearing for a stay, or a landlord may not be able to get a hearing to remove a tenant who is not paying rent.

These are difficult situations that deeply affect the people involved. Less obvious is that these types of delays can affect everyone.

The ABA task force summarized the situation this way: “The undue delay or outright denial of effective judicial action results not only in further harm to those who need prompt and fair resolution of their disputes, but also, in many instances, to more overcrowded prisons, threats to public safety, and harm to those, such as broken families, in the greatest need of legal support.”4

The Economy

We don’t often think about how budget cuts to the court system affect the economy. Yet the task force concluded that in California, for example, the reductions in court time, increased delays in processing cases, and other related expenses added up to much more than the projected “savings” to the state. Economic consultants calculated that the true costs of state-funding cutbacks would lead to new costs including the following: $13 billion in lost business activity resulting from decreased use of legal services; approximately $15 billion in economic losses due to additional uncertainty among civil litigants; close to $30 billion in lost output and more than 150,000 jobs lost from damage to the Los Angeles and California economies; and $1.6 billion in lost local and state tax revenue.5

As one business owner explained at a task force hearing, corporations decide where to locate their headquarters in part because of the judicial system. Underfunding reduces businesses’ confidence because it is not clear they will enjoy timely and effective legal protection.

An economic study found that in Florida in 2009, the backlog of mortgage foreclosure cases alone cost that state’s firms and residents $9.9 billion in additional legal fees, interest lost by financial institutions, and reductions in property values (over and above the “normal” declines from the general property market) because houses and offices remained vacant and were not properly maintained as a result of the delay in the foreclosure process itself.6

Such losses may have a ripple effect as they can deprive small family businesses of ancillary income to make ends meet for their other unrelated businesses – resulting in other business bankruptcies.

System of Government

The task force found that the potential effects of underfunded courts at the hands of the legislative and executive branches are so dramatic that the underfunding could undermine our tripartite form of government.

Courts have no direct power to raise money through taxes and cannot function properly without support from the other branches of government. The ABA task force points to an example in New York State, where 1,300 court of appeals judges went a decade without a cost-of-living pay increase due to partisan disputes. In 2010, the New York Court of Appeals concluded that the situation imperiled the separation of powers and ordered the pay increase.

In Maron v. Silver,7 the court explained that inflation had eroded judicial salaries in real terms by about 30 percent, while caseloads increased the same percentage to a “staggering” 3,500 cases for each judge.

The court noted that the governor and legislative leaders had publicly announced that the situation called for an immediate salary increase, but measures to do so had been defeated as they became embroiled in disputes over unrelated legislation.

Wisconsin’s Situation

Wisconsin has not reached the level of crisis found in some other states, but we need to be aware of what has happened elsewhere when courts are underfunded. We must change course if we want our courts to remain reliable, effective, and efficient. Some people have suggested that the only way to draw enough attention to the need for additional funding is to let the system fail. I don’t endorse such an approach. I would rather be proactive, and that’s why I am working to improve understanding of court funding in Wisconsin. We cannot afford to underfund our courts. We can learn a lot from places in which the problem went unaddressed too long.

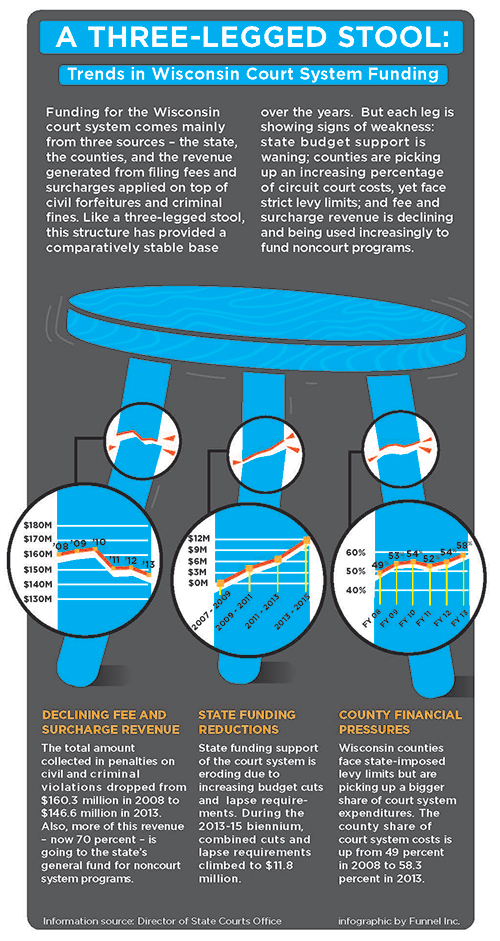

The structure of circuit-court funding in Wisconsin is a bit like a three-legged stool. The funding legs include the state, the counties, and fees and surcharge revenue. This structure has provided a comparatively stable base over the years. But each leg is showing signs of weakness, and the stability of each leg affects the others. Recent reductions in state funding are starting to have a destabilizing effect.

State Funding Restrictions

In addition to facing a $5.8 million cut in state appropriations during the 2013-15 state budget biennium, the court system must lapse to the state general fund another $11.8 million. Ironically, this requirement comes at a time when the governor subsequently called a special session to address the use of a projected $911.9 million surplus.8

In terms of overall state spending, this is a drop in the bucket. In fact, the state court system operates on about 0.85 percent of overall state tax dollars collected. In other words, less than one penny of each state tax dollar is used to support the state court system.

In her remarks to the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Finance last year, Wisconsin Supreme Court Chief Justice Shirley S. Abrahamson highlighted what the people of Wisconsin receive in return for this small investment9:

A justice system whose mission is to settle disputes peacefully in a fair, neutral, impartial, prompt, and nonpartisan manner according to the law, striving for equal justice under the law for everyone.

A justice system that protects the families of Wisconsin and helps make the state an attractive place to do business because commercial disputes are resolved fairly and promptly.

A justice system that protects constitutional rights guaranteed to all the people of Wisconsin by our own constitution.

A justice system that has been in the forefront of innovation in the administration of justice, including technological advances, problem-solving courts, and evidence-based practices.

However, Wisconsin residents are facing the largest funding reduction ever for the Wisconsin court system, and there are very few areas from which to cut because of constitutional or statutory considerations. For example, funding for positions such as judges and court reporters cannot be adjusted administratively, and these positions make up 70 percent of state court personnel costs. Unfortunately, there are few options to address these cuts.

The potential savings from the remaining budget areas do not add up without additional reductions in circuit court support payments to counties. This would be an unfortunate scenario that would further affect services provided to businesses and people who rely on the courts to timely settle disputes, large and small.

The ABA task force summarized the situation this way: “And since judicial budgets consist almost entirely of personnel costs, the courts do not have the ability simply to postpone expensive items to a more robust economic time; and thus reductions in court funding directly and immediately curtail meaningful access to the justice system. When that happens, the costs to society are great….”

Increasing state investment in the court system to just one penny per state tax dollar total would help stabilize this leg of the funding stool, as well as reduce stress on our county partners and help ensure that we are able to provide effective court services.

County Financial Pressures

Unfortunately, our county funding partners, who provide the second leg of the funding stool, do not have much wiggle room either. Counties face strict levy limits and have little ability to compensate for reduced state funding for court services. This puts tremendous pressure on counties to reduce court system costs. State aid to counties for court costs has not increased since 1999, and the amount has actually been reduced during the last several years. During state budget fiscal year 2008-09, counties received $18.7 million in circuit court support payments from the state. During state fiscal year 2012-13, counties received $16.6 million.

Counties also are picking up a larger percentage of circuit court costs – the amount has increased from 54 percent during fiscal year 2007-08 ($121.2 million) to 63.5 percent during the fiscal year 2012-13 ($177.9 million).

Financial pressures at the county level, driven in large part by the levy limits, are already affecting court services. For example, two years ago, the Buffalo County judge and clerk of court’s offices had a combined staff of six county-funded positions. That dropped to 4.25 positions specifically because of county funding issues, according to Chief Judge James Duvall, Buffalo County Circuit Court. Duvall’s Seventh Judicial Administrative District also includes Crawford, Grant, Iowa, Jackson, La Crosse, Monroe, Pepin, Pierce, Richland, Trempealeau, and Vernon counties.

Duvall notes, “This brings the focus to the circuit court support payment and highlights its importance. It is imperative we maintain adequate reimbursement for guardians ad litem (GALs), interpreters and county operational costs through the circuit court support payment to avoid blowing up already stressed county budgets. The damage of court funding shortfall will fall directly on the backs of counties and then, inevitably, on the court system. This is not just a courts issue, it is a county issue. There is nothing left to reduce in our county budgets without affecting the core functioning of one of the three independent branches of government.”

Other chief judges are hearing from judges in their districts about how funding pressure is affecting the quality of services, such as court interpreting. In an effort to cut expenses, one county reduced the use of certified court interpreters from 100 percent in 2010 to approximately 34 percent currently, according to Chief Judge Scott R. Needham, St. Croix County Circuit Court. Needham’s Tenth Judicial District also includes Eau Claire, Dunn, Chippewa, Polk, Barron, Rusk, Burnett, Washburn, Sawyer, Douglas, Bayfield, and Ashland counties. The cost of court interpreters is shared by the state and counties, but counties can save money by using interpreters who are not certified.

“Unfortunately, this has undone all of the hard work we have done during the last decade to increase the quality of court interpretation,” Needham said.

Declining Fee and Surcharge Revenue

The third leg of the funding stool – the amount collected in filing fees and surcharges imposed on top of fines and forfeitures – also is in decline. This is despite that the maximum total of penalties faced by an offender for any particular crime or violation has risen dramatically.

Because the clerk of circuit court in a given county is responsible for collecting payment from a litigant or offender, there may be a perception that the courts keep the money. However, this is not the case. Under the Wisconsin Constitution, a “fine” must go to the segregated school fund. So, to raise revenue, more than 35 fees and surcharges have been added to fines and forfeitures that go to fund other areas.

As a result, the total penalty on a “$100 fine” for a criminal violation increased from $155 in 1984 to $579 in 2014. And now, nearly 70 percent of the amount collected in fees and surcharges is sent to the state’s general fund or to other noncourt programs at the state level.

Just two of the fees and surcharges go to the court system and provide most of the funding for Consolidated Court Automation Programs (CCAP), the information and technology backbone of the court system. CCAP provides many vital services for the circuit courts, including a statewide system for managing cases, financial transactions, and juries, among other services.

The amount collected for CCAP has dropped 20 percent, or by $2 million, during the last five years due to reduced case filings and increased difficulties with fee collections related to state residents’ ability to pay. Because this revenue is the sole source of funding to operate CCAP in the circuit courts, this decrease is concerning.

Creating Awareness

The primary reason the Wisconsin court system has not yet experienced the severe service reductions that have occurred in other states is that our court funding structure is more diversified. States that have experienced the most significant problems are primarily state funded. In Wisconsin, county governments have been vital in helping maintain court services. Just like investing, the more diversified the portfolio, the better chance you have to weather a financial downturn. Unfortunately, all our “investments” are trending down. Unless steps are taken to address this, court services will suffer, and many people will be affected.

I am actively working with our partners in county government, the legal community, and others statewide to raise awareness of our funding situation and about the potential implications for public safety, the economy, property taxes, and the people who need rights protected and disputes settled. The stakes are too high to ignore.

As part of an effort to create awareness of the situation, I have begun traveling throughout the state talking with various groups, including judges, clerks of circuit court, and county officials. I recently addressed the State Bar of Wisconsin Board of Governors and am hoping that our justice system partners will be a part of a diverse and active coalition that can stem the trend. The recent creation of a court-funding committee through the State Bar is an encouraging development.

If Wisconsin is to be a strong state with strong communities, we need public safety, we need a strong economy, and we must protect people in need. Underfunding the court system diminishes our ability to do all these things.

New York Court of Appeals Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman said the courts have become “the emergency room for society’s worst ailments – substance abuse, family violence, mental illness, mortgage foreclosures, and so many more….”

Kremers puts it like this: “People come to court with the expectation of solving a problem or to get protection. It takes people, clerks, interpreters, attorneys, managers, court reporters, and judges, among others, to resolve those human dramas. We are not just processing pieces of paper; we are responding to human emergencies.”

Endnotes

1 ABA Task Force on Preservation of the Justice System.

2 “Crisis in the Courts: Defining the Problem.”

3 Atlanta Hearing, testimony of Atty. Manny Medrano. (From the ABA Task Force on Preservation of the Justice System, Report to the House of Delegates.)

4 Crisis in the Courts.

5 Weinstein & Porter, Economic Impact on the County of Los Angeles and the State of California of Funding Cutbacks Affecting the Los Angeles Superior Court (Dec. 2009).

6 21 Washington Economics Group, The Economic Impacts of Delays in Florida’s State Courts Due to Underfunding 10 (Feb. 2009).

7 14 N.Y.3d 230, 925 N.E.2d 800 (2010).

8 Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau letter to Joint Committee on Finance Cochairs, Jan. 16, 2014.

9 Wisconsin Supreme Court Chief Justice Shirley S. Abrahamson remarks to the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Finance.