By Nerino Petro and Bryan Sims

June 16, 2010 – Metadata is a term that is appearing more frequently in legal circles. Since August 2006, several bar associations have issued formal ethics opinions addressing the ethical implications of the disclosure of information via metadata. Given the ubiquitous manner in which attorneys regularly exchange documents, the ethics involved in metadata is a topic that will likely rise with even greater frequency in the near future.

In this article, we discuss what metadata is and why attorneys should be concerned about it. We then review the opinions issued by the various bar associations and analyze them in the context of the duties imposed upon attorneys when they send electronic documents and when they receive electronic documents from other attorneys. Part II of this article, which will appear in the July 7 issue of InsideTrack, will address proper methods of redaction.

As you will see from the information below, some metadata may be important from an evidentiary perspective. These materials discuss the implications of metadata in exchange of documents between counsel and do not address the use of metadata in the discovery process.

Metadata: What is it?

The first question to address is: What exactly is metadata? The typical definition of metadata is that it is “data about data.”1 One federal court has defined metadata as “the history, tracking, or management of an electronic document,” including such useful information as file names, location, format, creation and access dates, and user permissions.2 As a practical matter, neither of these definitions is particularly useful, although the second provides a little more information than the first.

From a realistic perspective, metadata is information about an electronic file that is not readily apparent simply by viewing the file. A key to understanding metadata is understanding that metadata in and of itself is not bad. All electronic files have some form of metadata.

Unfortunately, some files have more metadata than others due to the amount and type of metadata that the program used to create it stores or adds to the file.

One simple way of viewing metadata in a Microsoft Word® or Office file is to go to Windows Explorer, right mouse click on a file, and then select Properties from the drop down menu.

This step reveals information such as the location of the file, the date and time the file was created, the date and time the file was last modified, and the date and time the file was last accessed. A user can also do this from inside MS Word or other programs as well.

Similarly, if you have ever clicked on a hyperlink in an email, document, or a webpage, you have used metadata. The link you clicked on may have been the title of a document or article, but encoded in that text was metadata that instructed the computer how to navigate to a location, such as a web page.

Similarly, metadata is created any time that you create, access, modify, save, move, copy, or do anything else to a file. The operating system uses this information to keep track of files. For example, sorting files in Windows Explorer or dialog boxes by name, size, modified date, and so on, is possible only because of the metadata contained within the files.

Additional metadata is created when using certain features in programs, such as the track changes feature in MS Word. The former type of metadata can be easily viewed simply using Windows Explorer or while the latter can be viewed by turning on the track changes feature in MS Word.

From this, we know a couple of things. First, metadata is ubiquitous: it cannot, nor should it be, avoided. Second, some metadata is easily accessible without the use of any special tools and without difficulty. Thus, any time that you send an electronic file to another person, you are providing that person with information in the metadata.

The key, of course, is to understand what metadata you are sending.

For example, you could have a draft settlement agreement that contains information (in track changes or comments) indicating that your client would like a particular provision, but will compromise on it to get the deal done. Obviously, this is not information that you want the other side to discover.

This issue can lead to real problems. For example, in January 2003, a British dossier on Iraq’s security infrastructure was released. A review of the metadata in the document revealed that, rather than being created by British intelligence agencies, the document was actually compiled by copying works prepared by others, including a post graduate student at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. See http://tinyurl.com/frqt for further information about this story.

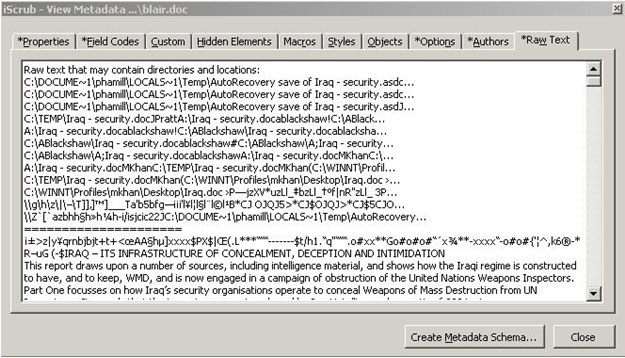

That document was available on the internet and a review of the document with a program that reveals metadata shows that the document was stored in locations such as phamill’s temp directory, ABlackshaw’s directory, and MKhan’s directory, as shown in the following image:

This is just one of many examples of people releasing information to others via metadata without intending to.

Knowing what metadata “is” leads us to two concerns: (i) how to manage metadata when you send a document to someone else; and (ii) what to do about metadata when receiving a document from someone else.

Duties as a sending attorney

As a creator and sender of an electronic document, the duties in managing metadata are fairly simple. Wisconsin Supreme Court Rule 1.6(a) of Ch. 20A relating to Rules of Professional Conduct for attorneys provides that: “(a) A lawyer shall not reveal information relating to the representation of a client unless the client gives informed consent, except for disclosures that are impliedly authorized in order to carry out the representation, and except as stated in pars. (b) and (c).”

Although no Wisconsin decision has directly addressed metadata and whether or not an attorney needs to take precautions to prevent the disclosure of metadata that could violate rule 1.6(a), the rule does not limit itself to only hard copy information.

Therefore, it seems that an attorney should take reasonable precautions to ensure that electronic documents sent to others do not contain confidential information.

Comment 16 to rule 1.6(a) seem to add additional credence to this position when it states: “A lawyer must act competently to safeguard information relating to the representation of a client against inadvertent or unauthorized disclosure by the lawyer or other persons who are participating in the representation of the client or who are subject to the lawyer's supervision.”

And comment 17 to rule 1.6(a) recognizes the potential dangers when transmitting a communication: “When transmitting a communication that includes information relating to the representation of a client, the lawyer must take reasonable precautions to prevent the information from coming into the hands of unintended recipients.”

The decisions from the jurisdictions that have addressed the question of a sending attorney’s perspective support this conclusion. For example, the Florida Bar opinion provides: “In order to maintain confidentiality … lawyers must take reasonable steps to protect confidential information in all types of documents and information that leave the lawyers’ offices, including electronic documents and electronic communications with other lawyers and third parties.” The Florida Bar, Ethics Opinion 06-2, 2.

In fact, the Florida opinion goes so far as to provide that professional responsibility “may necessitate a lawyer’s continuing training and education in the use of technology in transmitting and receiving electronic documents in order to protect client information.” Id. at 4.

Closer to Wisconsin, the Minnesota Lawyers Professional Responsibility Board issued Opinion 22 – A Lawyer’s Ethical Obligations Regarding Metadata on March 26, 2010, which held:

A lawyer has a duty under the Minnesota Rules of Professional Conduct (MRPC), not to knowingly reveal information relating to the representation of a client, except as otherwise provided by the Rules, and a duty to act competently to safeguard information relating to the representation of a client against inadvertent or unauthorized disclosure. See Rules 1.1, 1.6, MRPC. The lawyer’s duties with respect to such information extends to and includes metadata in electronic documents. Accordingly, a lawyer is ethically required to act competently to avoid improper disclosure of confidential and privileged information in metadata in electronic documents.

Of those entities that have taken a position on metadata and an attorneys duty, all have found that the sending attorney is required to take reasonable steps to prevent the inadvertent disclosure of metadata. This makes things relatively easy – take steps to ensure that sent documents do not contain metadata that you aren’t ready to share with the world.

A number of bar associations (including Florida and Minnesota) have issued opinions that relate to metadata and the obligations of attorneys under the rules of professional conduct.

As with many things in the law, not all jurisdictions agree as to the requirements for sending and receiving attorneys. The American Bar Association’s Legal Technology Resource Center has compiled a useful reference chart of all U.S. decisions to date which can be found in its Metadata Ethics Opinions Around the US chart.

How to remove metadata

A sending attorney can remove or otherwise manage the metadata in a document through a variety of methods. An ABA opinion discusses several methods of managing metadata in a document, including such things as not using redline or track changes features in software programs, sending only hard copies of documents, printing and scanning documents before sending an electronic version, and negotiating a confidentiality or claw back agreement with opposing counsel. American Bar Association, Formal Opinion 06-442, 5.

Although these methods suggested by the ABA are possible methods of managing metadata, other electronic means are available that make managing metadata quick, easy, and effective.

The key is to ensure compliance with ethical obligations to keep confidential information out of the hands of third parties, while continuing to leverage the power of electronic documents.

The first method is to use built-in metadata removal tools. For example, WordPerfect X3, MS Office 2007, and Adobe Acrobat (starting with version 8) include metadata removal tools that you can use from within the programs themselves.

For example, in WordPerfect X3, to remove metadata, simply choose File > Save Without Metadata. In MS Word 2007, select the MS Office Button > Prepare > Inspect Document, and then select Remove All. 3

These options work fine as long as you remember to use them before you send a file to someone else. However, they have two significant failings. First, they rely on your memory to ensure they get used. Second, they provide no assurance that other people in your office either know how to remove the metadata or remember to do so.

As a result some third party products have been developed that integrate with MS Outlook to ensure that you don’t accidently email a document without first checking it for metadata. These programs include: Metadata Assistant, from the Payne Group; iScrub by Esquire Innovations, Inc.; Workshare Protect; and Metadact by Litera Corp.

These programs operate by detecting attachments to emails and then asking to scrub the files of metadata. Most allow you to customize the types of information that is removed. Further, an enterprise can employ these tools in a way that prevents anyone in the organization from sending out a document with any significant, let alone confidential, metadata.

Duties as a receiving attorney

When it comes to the question of what a receiving attorney can or should do with a document that he has received, that is where the formal opinions are a bit contradictory.

For example the opinions from the ABA, Colorado, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Minnesota4 conclude that an attorney is permitted to view metadata found in an electronic document that he has received. On the other hand, Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Maine, New Hampshire, New York , Washington D.C., and West Virginia prohibit an attorney from viewing this metadata.

The decisions as to the proper actions to take by a receiving attorney are a bit convoluted. However, the ABA Legal Technology Resource Center’s Metadata Ethics Opinions Around the US chart summarizes the various decisions that have been published, including the Minnesota decision.

Conclusion

Electronic files are a fact of life for lawyers and law firms and so is the need of continued compliance with the rules of professional conduct. While the rules were drafted at a time when metadata and electronic redaction weren’t contemplated, reality and technology is forcing lawyers to adapt and overcome any lack of guidance on these issues.

With a lawyer’s obligations to supervise staff and associates and to safeguard the confidentiality of a client’s information, the authors believe that in order to comply with the competency requirement mandated by the rules, lawyers need to have at least an awareness, if not an understanding, of the issues that can arise from the failure to remove harmful metadata from electronic documents before sending them outside of the office.

The July 7 issue if InsideTrack will include “Avoiding ethical pitfalls with electronic documents: Part 2 – Redaction” addressing the problems and solutions concerning the redaction of confidential information from electronic documents.

Metadata Removal Software:

Metadata Assistant http://www.payneconsulting.com/products/metadataretail/

iScrub http://esqinc.com/section/products/2/iscrub.html

Workshare Protect http://www.workshare.com/products/wsprotect/

Metadact http://www.litera.com/products/metadact.html

Nerino J. Petro Jr. is the practice management advisor for the State Bar of Wisconsin’s Law Practice411TM program. He assists lawyers in improving their efficiency in delivering legal services and in implementing systems and controls to reduce risk and improve client relations. You can reach Petro at (800) 444-9404, ext. 6012; practicehelp@wisbar.org.

Bryan Sims, Naperville, Ill., is the sole shareholder in Sims Law Firm, Ltd., where he concentrates his practice in the areas of commercial litigation and civil appeals. Bryan has spoken on legal technology issues for both the Illinois State and Chicago bar associations. He was named the 2005 TechnoLawyer of the year. Bryan blogs at www.theconnectedlawyer.com.

1See, e.g., http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metadata.

2Williams v. Sprint/United Mgmt. Co., 230 F.R.D. 640, 646 (D. Kan. 2005).

3If you are using Microsoft Office 2003, the metadata removal tool can be downloaded from http://www.microsoft.com/downloads/details.aspx?FamilyID=144e54ed-d43e-42ca-bc7b-5446d34e5360&displaylang=en.

4The Pennsylvania and Minnesota opinions require attorneys to evaluate this on a case-by-case basis.