Vol. 78, No. 5, May

2005

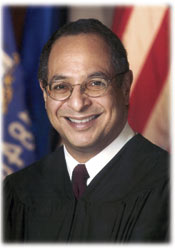

Aiming High

Throughout his 13-year judicial career, Louis Butler has believed

that being a judge involves much more than judging. Now that he's the

Wisconsin Supreme Court's newest justice, he still thinks so.

by Dianne Molvig

Two suitcases sit near the window in Justice

Louis Butler's Wisconsin Supreme Court office, creating the impression

that he has a flight to catch later in the afternoon. Perhaps he'll be

heading out to speak at a conference or to teach at the National

Judicial College in Reno, Nev. - the sorts of trips he takes

regularly.

Two suitcases sit near the window in Justice

Louis Butler's Wisconsin Supreme Court office, creating the impression

that he has a flight to catch later in the afternoon. Perhaps he'll be

heading out to speak at a conference or to teach at the National

Judicial College in Reno, Nev. - the sorts of trips he takes

regularly.

But, in fact, on this particular March afternoon he has no plans to

fly anywhere, and those two suitcases are standing ready nearby, as they

do every day, to serve other purposes.

Seated at his desk, Butler gestures toward the bags and says, "The

bigger of the two I fill with my reading." It goes home with him to

Milwaukee on weekends and looks to be about the size most people would

find adequate to pack for a week-long trip. "The other one," he says of

the smaller bag, which has at least triple the capacity of an ordinary

briefcase, "I take home every night (to his Madison apartment) filled

with reading material for the next day."

Toting those paperwork-stuffed bags back and forth has become part of

Butler's normal routine since he was sworn in last August as the newest

supreme court justice, on appointment by Gov. Jim Doyle.

"I thought I knew what this job entailed," Butler says, "because I

did appellate work for nine years (with the Wisconsin State Public

Defender's Office). One of the things you learn when you get here is

that whatever you think this job entails, get out your multiplier. It's

a heck of a lot more."

He's been surprised to learn, for instance, how much justices must do

in addition to deciding cases. Rule making, disciplinary matters, public

speaking engagements, overall court administration, and case selection

all devour considerable time. "There are petitions for bypass, for

certification, for original action - we get about 1,200 of those a

year," Butler explains. "You don't think about the 1,200 petitions

you're going to read; you only think about the cases the court is going

to decide. At least that's the way I thought when I walked into this

job."

This all adds up to a professional life that allows sparse down time,

and even sleep becomes a rare commodity, Butler admits. Yet, sitting at

his desk, he looks and sounds like someone who's recently returned from

a month's vacation. He talks energetically, easily breaks into his

characteristic hearty laugh, and shows no hint of feeling overworked.

Clearly, this is a guy who is exactly where he wants to be, doing what

he wants to do.

Hooked Early

Butler's aspiration to join the state's highest court - one of many

goals he has set for himself in his 53 years - dates back to the late

1980s, before he'd yet been a judge of any type. As early as age eight,

he decided he wanted to be an attorney. "I was hooked by John Kennedy's

inaugural speech," he says. "I saw it as a call to public service, and

I've been on that career path ever since."

Part of the reason for wanting to be a lawyer was to be able to clean

up neighborhoods like the one where he grew up on Chicago's south side.

"We were surrounded by the two largest street gangs in the nation at

that time," he says. "We made a pact on our block that we weren't going

to join a gang. We kind of stuck together."

Still, it wasn't an easy pact to keep. Violence was everywhere, as

were the threats to those who wanted no part of it. Butler remembers,

for instance, his brother once running into the house, dodging bullets,

and his mother, livid that anyone would endanger her son, about to run

out to give the hoodlums a piece of her mind, armed with only a broom.

His brother had to pin her in his arms to stop her.

"I knew - everyone knew - who the bad people were in the

neighborhood," Butler says, "but things weren't happening to stop them."

Thus, the young Butler decided to become an attorney, and perhaps one

day the first black mayor of Chicago. He never pursued the latter goal,

but the other goal he reached in 1977 when he received his law degree

from the U.W. Law School, Madison, after earning his undergraduate

degree at Lawrence University in Appleton.

Upon graduation from law school, Butler originally had his sights set

on becoming a criminal prosecutor. "I love criminal law - the nuances,

the issues that come up," he says. But he ended up getting his first job

as an appellate attorney in the State Public Defender's Office (SPD),

which he describes as a "top-notch criminal law agency." Nine years

later he switched to the SPD's trial division.

"It's one thing when you're reviewing transcripts as an appellate

lawyer and seeing how you think the case should have been tried," Butler

points out. "It's another to be in the trenches trying the cases."

He decided he wanted the latter experience, as well. So, three days

after he argued a case in the U.S. Supreme Court (the first Wisconsin

SPD attorney ever to do so), he handled a misdemeanor intake on his

first day with the SPD trial division. He stayed there four-and-a-half

years, until he was appointed to the Milwaukee County municipal bench in

1992.

Butler's judicial aspirations actually had taken root a few years

earlier. In 1989, he ran unsuccessfully for Milwaukee County circuit

court, following three earlier attempts to earn appointments to the

circuit court. After 10 years as a municipal judge, in 2002 Butler again

sought and this time won a circuit court judgeship, earning two-thirds

of the votes.

By that time, he'd also made a run for the state supreme court in

2000, without success. In typical Butler fashion, he views that loss as

a positive, in the end. He notes that had he not been in that race, he

wouldn't have caught the attention of the Judicial Selection Committee

and the governor last summer.

"I think it's important to get out there," Butler says. "I remember

something a gentleman told me a long time ago, when I first expressed an

interest in the judiciary. He said, `You know, you haven't shown you're

serious. You haven't run.' That stuck with me ... I never want to be in

a position where I have to look back and say, `What if I'd done this or

that?' For me, failure is not in trying and failing; failure is in not

trying."

Reaching Out

Through all his years as a judge, on whatever bench he was serving at

the time, Butler has made it a priority to get out to talk to young

people. Incidents over the years have convinced him of the importance of

appearing before such audiences.

For instance, about 10 years ago he served as a judge for a gumbo

cooking contest at Milwaukee's Silver Spring Neighborhood Center. "My

mother's side hailed from Louisiana on their way to Chicago," he says of

his credentials. "So we cooked gumbo in my family. I cook gumbo."

At the contest, all three gumbo judges were, in fact, Milwaukee

County judges - Stanley Miller (now deceased), Russell Stamper, and

Butler - and they were introduced as judges to the community center

crowd. As they performed their culinary judging duties, they couldn't

help but notice a group of African-American teenage boys seated at the

foot of the stage, staring at them. It got to the point that one of the

three judges, all of whom were also African-American, felt compelled to

ask the young men if they needed something.

"I'll never forget the look on one young man's face," Butler recalls,

"as he looked up at the three of us and said, `I've never seen a black

judge before.'"

Usually, when he appears before young people, Butler is talking, not

tasting. He speaks about what he knows: the value of trying even if you

end up failing, working hard for what you want, and setting your goals

high.

"I have this theory that whatever your goals are in life," he says,

"you're going to fall just short. If your goal is way up here, even if

you fall short you'll have done so much. If your goal is way down here,

you have nowhere to go. I really believe that."

He also talks to youth about not letting others block their way. One

of Butler's high school counselors, for instance, once told him he

wasn't smart enough to get into U.W.-Madison. Years later, having been

admitted to the U.W. Law School, "I got my revenge," he says with a

laugh.

There's one other topic Butler can speak to, a subject he knows well

and that resonates with many of his young audiences: how to survive

day-by-day in a tough neighborhood. He tells his stories about being

determined to stay out of gangs, of getting beaten on his first day at

Chicago's South Shore High School because he wouldn't surrender his

lunch money to pay gang dues.

"I was at the Urban Day School in Milwaukee about two weeks ago,"

Butler says, "and I was watching the recognition on their faces (as they

related to his experiences). These were fifth and sixth graders. These

things are happening to them now. They need help now, not later."

The Urban Day School is just one of Butler's many recent and upcoming

speaking venues: North High School in Appleton, Gateway Technical

College in Kenosha, a United Auto Workers banquet in Kenosha, the U.W.

Law School's Legal Education Opportunities banquet, the East High School

commencement in Madison, a Zion Missionary Baptist Church dinner in

Milwaukee, the St. Patrick's Day parade in Madison, Superior High School

... and the list goes on.

Normally, he does several speaking engagements each week. On the

suggestion that perhaps he's doing more of these than he would need to

do, in light of his already hefty workload, Butler laughs and responds

simply, "Who, me?"

Making History

Butler knows, and his colleagues assure him, that the day will come

when it will get easier to keep pace with his job demands and he'll have

more time for his family. "I also have to figure out how to work golf

into my schedule," he adds. "I haven't seen a golf club in a long time,

and it's getting to be that time of year."

But this mid-March afternoon, a Friday, the suitcases sit waiting by

the window. The bigger one soon will be loaded with briefs, petitions,

and other paperwork that will consume Butler's weekend at home in

Milwaukee.

"It does take a tremendous amount of energy to do this job

correctly," he says, "and I feel strongly about doing it correctly. I

understand that I am but one of seven, and in the scheme of seniority, I

am No. 7. As a member of this court, I can do nothing unless I can

persuade three others to join me. The only way you can do that is if you

are prepared. I have to read this stuff. I have to figure out how to

talk to my fellow justices about how we're going to decide these issues.

I have a great deal of respect for the people I work with, because I

know what they're putting into this job. I know how hard they work

because I know what I'm doing."

As he performs his daily tasks of reading, writing, conferring with

court colleagues, and speaking to outside groups, Butler also is doing

something else by just being here. He's making history as Wisconsin's

first African-American supreme court justice.

The state's historical accounts will make note of that fact for many

decades to come, long after Butler is gone. How else would he like to be

remembered someday for his tenure on the state supreme court?

"When people look at my decisions 20 years from now," he says, "I

would hope most people will see me as a justice who worked hard to

interpret and apply the law, and who cared about our Constitution. I

hope they'll see that I cared about process, not results. I don't think

it's appropriate to decide a case and then figure out how to get there.

I think you let the process take you where you need to go."

Dianne Molvig operates Access

Information Service, a Madison writing and editing service. She is a

frequent contributor to area publications.

Wisconsin Lawyer