Maximum enlightenment requires maximum education. Blacks have

traditionally stressed education even at the risk of death during

American slavery. It's up to those of us who recognize what education

can do to demand that teachers teach, educators educate, students learn

and that school[s] serve as places for enlightenment rather than holding

tanks for ignorance, [or] fosterers [of] drop outs, cop outs and

scapegoats."1

* * *

Wisconsin's image of itself as a progressive state has not always

matched reality in the field of race relations. Black suffrage was

defeated several times at the polls before a favorable decision was

obtained in 1866 from the Wisconsin Supreme Court by early civil rights

pioneers Ezekiel Gillespie and Judge Byron Paine of Milwaukee.2 Several antidiscrimination statutes were enacted

in Wisconsin before World War II with the help of black lawyers such as

William T. Green and George De Reef, but the laws were seldom enforced

and de facto segregation was common.3

Wisconsin's image of itself as a progressive state has not always

matched reality in the field of race relations. Black suffrage was

defeated several times at the polls before a favorable decision was

obtained in 1866 from the Wisconsin Supreme Court by early civil rights

pioneers Ezekiel Gillespie and Judge Byron Paine of Milwaukee.2 Several antidiscrimination statutes were enacted

in Wisconsin before World War II with the help of black lawyers such as

William T. Green and George De Reef, but the laws were seldom enforced

and de facto segregation was common.3

Since that time the struggle for equality has forced Wisconsinites to

confront segregation and discrimination repeatedly, a process that has

continued to this day.

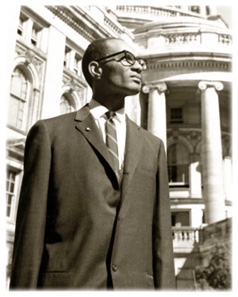

Lloyd Barbee, a lawyer, a legislator, and an influential voice for

the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP),

led the modern civil rights movement in Wisconsin for many years.

Barbee's gentle manner concealed an iron determination that served him

and his cause well. Barbee occupies a unique place in Wisconsin legal

history and civil rights history. He was a skilled lawyer, an

influential state legislator, an active NAACP member and leader from a

young age to his death, and a courageous proponent of legislation

promoting race and gender equality and prison and court reform. Barbee

was a visionary: he regularly took up causes that would not be

confronted by society at large until years later, such as gay rights and

abortion. This article tells only a small part of his story. In this

year marking the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in

Brown v. Board of Education,4 it is

fitting to recognize Wisconsin's most influential figure in implementing

that decision.

Early Years: Memphis to Milwaukee

(1925-1960)

Lloyd Barbee was born in Memphis, Tenn., on Aug. 17, 1925, the

youngest of three sons of Earnest and Adlena (Gilliam) Barbee. His

mother died when he was six months old.5 At

an early age Barbee embraced his father's and brothers' love of the

arts, listening to classical music and literature on the radio. From the

very beginning he showed signs of being someone special.6

Judge Maxine Aldridge

White, Marquette 1985, 2001 State Bar Judge of the Year, has

been a Milwaukee County circuit court judge for 12 years. Born the

eighth of 11 children to grade-school educated sharecroppers and raised

in the Deep South during the era of Jim Crow, she experienced racial

segregation and is a direct recipient of the opportunities resulting

from the sacrifices of Lloyd Barbee and others.

Judge Maxine Aldridge

White, Marquette 1985, 2001 State Bar Judge of the Year, has

been a Milwaukee County circuit court judge for 12 years. Born the

eighth of 11 children to grade-school educated sharecroppers and raised

in the Deep South during the era of Jim Crow, she experienced racial

segregation and is a direct recipient of the opportunities resulting

from the sacrifices of Lloyd Barbee and others.

Joseph A. Ranney, Yale 1978, is a trial lawyer with

DeWitt Ross & Stevens S.C., Madison. He is the author of Trusting

Nothing to Providence: A History of Wisconsin's Legal System (1999) and

has taught as an adjunct professor at Marquette University Law

School.

Joseph A. Ranney, Yale 1978, is a trial lawyer with

DeWitt Ross & Stevens S.C., Madison. He is the author of Trusting

Nothing to Providence: A History of Wisconsin's Legal System (1999) and

has taught as an adjunct professor at Marquette University Law

School.

Barbee grew up in the Depression South, which was highly segregated

in every aspect of life. Although his family did not suffer the immense

poverty that marked the lives of many black Americans in the

1920s,7 Barbee's father taught him early on

about the hard times that he and other blacks experienced. Racial

prejudice was part of Barbee's everyday life in Memphis, but he was

fortunate to grow up in a family that challenged preconceived limits and

urged him to fight injustice.8 Barbee's

father was a painting contractor, the first African American member of

the [Tennesee] state contractor's union.9

His uncle also was a businessman, employing about 10 people building

houses and churches. The Barbee family also included many teachers, who

helped to ingrain in Barbee a love of learning and a thirst for

knowledge.10 His father was fascinated by

great orators and exposed Lloyd and his brothers to grand speakers and

the "art" of protest at an early age.11

Barbee attended segregated schools and joined the NAACP at the age of

12. At age 17 he experienced what he described as "outrage" when noted

activist A. Philip Randolph came to Memphis and black church leaders

were afraid to let Randolph speak in their churches about war and civil

rights. Lloyd was very upset that the church leaders "had no

backbone."12

After high school, Barbee served in the Navy from 1943 to 1946. While

remaining active in the NAACP, he attended LeMoyne College in Memphis,

earning a B.A. degree in 1949. Faced with threats to his safety and

disgusted with the atmosphere of the Jim Crow South, Barbee concluded

that there was no future for him in Memphis. He moved to Madison in 1949

to attend law school on a scholarship at the University of Wisconsin,

joining other early African American trailblazers at virtually all-white

universities.

Regrettably, life in Madison gave Barbee "new insights into the many

shades of discrimination" and brought home to him the fact that racial

prejudice was not confined to the South.13

He sadly realized that "conscious racial discrimination was common, and

unconscious racism among the educated was appallingly common."14 Angry about racial slights at the U.W. Law

School, Barbee dropped out after his first year but later returned and

earned his law degree in 1956.15 He

continued his affiliation with the NAACP, rising to become president of

the Madison chapter in 1955. In 1961 he was elected president of the

state branch of the NAACP.

After graduating, Barbee encountered difficulties in earning a living

as a black lawyer. He worked as an examiner for the state government and

served on both the state and Madison human rights commissions. In 1958

he initiated an in-depth report on racial discrimination in housing in

Madison, the first such report done on a Wisconsin city. In 1961 he

organized his first sit-in, a 13-day, round-the-clock vigil at the State

Capitol rotunda in support of fair housing and equal opportunity

legislation - the first demonstration of this type in the nation. In

1961 he succeeded in changing the name of Nigger Heel Lake in Polk and

Burnett counties, Wis., to Freedom Lake. Barbee also drafted the

proposal for the first comprehensive civil rights ordinance, which

subsequently passed in 1964 as the Madison Equal Opportunity

Ordinance.

The Fight to Desegregate Homes and Schools in

Milwaukee (1960-1976)

The turmoil generated in the South by the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954

decision in Brown and by Dr. Martin Luther King's civil rights

crusade16 did not reach Wisconsin and other

northern states until the early 1960s. In 1962 Assemblyman Isaac Coggs,

who was already fighting for stronger enforcement of Wisconsin fair

employment laws, encouraged Barbee to move to Milwaukee and run for an

Assembly seat. Barbee met with NAACP general counsel Robert Carter, who

was a leading attorney with Thurgood Marshall in the Brown

trial, to discuss strategies for dealing with school desegregation in

Northern cities. Carter and Roy Wilkins, head of the national NAACP, had

identified Barbee as "a skilled lawyer who understood the complex and

evolving case law on Northern school segregation" and as an "experienced

protest organizer."17 They encouraged

Barbee to move to Milwaukee and energize the local NAACP, and in late

1962 Barbee moved to the city that would remain his home for the rest of

his life.18

Commemorating the Struggle for Equality, Brown v. Board of

Education

America's circuitous march toward equality has changed our society

and our institutions and has profoundly reshaped the nation's attitudes

and values. The law has been instrumental in these changes, and has been

influenced by them in turn. Through law and the courts, one group of

Americans after another has redefined "equality" in a fiercely

contested, still ongoing process.

Significant in this process is the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 ruling

in Brown v. Board of Education. Brown struck down laws

segregating public schools, sounded the death knell for

government-sanctioned segregation generally, made all Americans more

aware of our Constitution's promise of equality, and helped launch the

civil rights movement.

To help celebrate the 50th anniversary of Brown, the State

Bar of Wisconsin hosts the following events:

State Bar Annual Convention, May 5-7, 2004

-

On May 6, NAACP Chair Julian Bond keynotes the spotlight program

"Civil Rights: Now and Then - Brown v. Board of Education: 50

Years Later." The Thursday morning program will be followed by a panel

discussion reflecting Brown's impact on Wisconsin law,

moderated by State Bar president-elect Michelle Behnke.

-

At Thursday's speaker showcase CLE luncheon, discussions of equality

continue with "Access to Justice: How Do We Make It Happen?" Speakers

and panelists will include Gov. James Doyle (invited), Chief Justice

Shirley Abrahamson, Rep. Mark Gundrum, and Attorney General Peggy

Lautenschlager.

-

"... with all deliberate speed..." (From Brown v. Board of

Education), a Thursday afternoon panel presentation by the

Diversity Outreach Committee and Government Lawyers Division, concludes

the Bar's formal look at Brown and issues of equality and

access to justice and education.

Law-related Education and Public Outreach

Programs

-

The Diversity Outreach Committee worked with a social studies

teacher to develop a lesson plan from ABA materials on Brown to

assist lawyers with school presentations. In late winter, lawyers

visited schools in Dane, Milwaukee, and Waukesha counties to share

information on the history of civil rights, issues in education, and law

as a career.

-

The Law-related Education Committee worked with the state Department

of Public Instruction to develop materials and lesson plans to assist

lawyers and judges in making presentations on Brown.

-

The Bar helped to underwrite the costs of a Law Day luncheon

celebration cosponsored by the Office of the Chief Justice and the

Wisconsin Legal History Committee. Held at the state Capitol on Monday,

April 26, the event brought together students and educators to hear from

people who attended segregated schools. The program emphasized the

pre-Brown struggles and the importance of the law and education

in the lives of Wisconsin's young people.

-

Marquette University Law School (with the State Bar as cosponsor)

created two conferences. On April 8, the program "Segregation and

Resegregation: Wisconsin's Unfinished Experience" explored the road to Brown. An October program (TBA) will look at present and future

issues in education.

Local operation and control of schools had long been a cornerstone of

Wisconsin's education system, and the Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) had

operated a neighborhood-based school system for many years.19 In response to the Brown decision, MPS

in 1958 began a program known as "intact busing," under which large

numbers of black students and teachers were bussed to white schools but

remained in segregated classrooms.20 Up to

1962, both Milwaukee housing and schools had proven resistant to

integration. As a result, most blacks lived in the city's "Inner Core"

area, which was plagued by substandard living conditions.21 At that time, blacks made up approximately 6

percent of Milwaukee's population. By 1965 blacks represented 10.2

percent of the city's population. A 1960 report concluded that Milwaukee

had the most pronounced pattern of racial separation in the

nation.22 Barbee saw a chance to attack

segregation in Milwaukee by using the strategy, first employed in the

case of Taylor v. City of New Rochelle (1961), of

showing that although residential segregation contributed to school

segregation, "the [school] board's own actions (and inactions) had

reinforced and intensified the racial segregation."23

Barbee quickly impressed his new neighbors in Milwaukee: in 1962 he

was chosen to head the Milwaukee branch of the NAACP and in 1964 he was

elected to the Assembly, where he served for six terms.24 Barbee's constituents wanted quick action to

combat segregation, and they got it. A few weeks after his election to

the Legislature, Barbee demanded that MPS desegregate its schools and

presented a desegregation plan that called for selective busing to

achieve a more even racial balance in the schools. Barbee's demand

triggered a sharp internal struggle within MPS. The conservative faction

prevailed: MPS informed Barbee that neighborhood schools had to be

preserved at all costs and that selective busing was not

acceptable.25 Barbee responded by warning a

meeting of Milwaukee lawyers that racial injustice was not confined to

the atrocities then taking place in the South but also existed at home.

"If the Brown decision means anything," said Barbee, "it means

that school segregation is unconstitutional wherever it exists, north or

south."26

During the mid-1960s Barbee repeatedly reminded Milwaukeeans that

their schools violated the U.S. Supreme Court's holding in

Brown that segregation was inherently unequal. As evidence,

Barbee relied upon the increasing numbers of mostly black schools and

MPS's practice of placing black teachers only in black schools. He

called upon school administrators "to act affirmatively" to eliminate

segregation or risk a legal battle in the courts and mass protests in

the streets. Both local white authorities and the established black

leadership responded defensively to Barbee's charge of segregation. They

argued that segregation in Milwaukee was due to geographic patterns over

which they had no control, and they suggested that Barbee "attack job

discrimination and housing discrimination" instead.27

Barbee formed a desegregation coalition of community leaders who

supported his cause, and in January 1964 he led the coalition in its

first confrontation with MPS. The meeting began with school board chair

and attorney Harry Story directing Barbee to be seated apart from the

other members of his coalition. Barbee resisted this attempt to split up

the coalition and walked out of the meeting. This action cemented

Barbee's reputation as someone who would not compromise his values and

made him a hero to some factions, because he passed up a clear chance to

enhance his own personal importance in favor of maintaining unity and

preserving the coalition.

Later that year, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visited Milwaukee,

he complimented Barbee by stating: "Several months ago, the Northern

Negro arose from his apathetic slumber." Dr. King encouraged

Milwaukeeans to follow Barbee's lead, stating that: "A school boycott is

a creative way to dramatize the whole issue."28

After a series of marches and demonstrations failed to move MPS,

Barbee and the NAACP formed the Milwaukee United School Integration

Committee (MUSIC) in 1965. MUSIC organized a boycott of public schools

and created "Freedom Schools" to take their place. MPS responded by

creating an "open transfer" policy, which made it easier for black

students to transfer to schools outside the inner city but did not

require white students to leave their neighborhoods. The new policy

backfired: many white students left the few remaining integrated

Milwaukee schools, and black students who went outside the inner city

for their education often ended up in segregated classes.29

Barbee soon concluded that black Milwaukeeans had a better chance of

achieving integration through the courts than through lobbying MPS. In

July 1965 he filed a suit in federal court, Amos v. Board of School

Directors of the City of Milwaukee. Barbee argued that even though

MPS had not maintained an official policy of segregation, the pattern of

segregation that had developed in Milwaukee since the 1940s violated the

right of black students to equal protection under the law. The

Amos case turned into a battle of epic proportions, consuming

eight years of discovery and preparation before it went to trial.

Barbee faced opposition not only from MPS officials but also from

people who agreed with his aims but disagreed with his timing and

tactics. Even the national NAACP came to believe that the public school

desegregation battle could not be won at that time in Milwaukee. It felt

that prospects for success were greater in Cleveland and devoted its

resources to that city. Barbee was largely left to fight on his own

without significant help until Judge John Reynolds appointed counsel to

assist him as the trial approached. Ironically, the NAACP lost the

Cleveland case, while Barbee eventually emerged victorious in

Milwaukee.30

Barbee faced not only occupational risk but also the risk of physical

danger as a result of his stand for justice. Violence against civil

rights activists was all too common in the 1960s. On March 7, 1965, only

four months before Barbee filed the Amos case, approximately

600 civil rights marchers in Alabama were attacked with clubs and tear

gas by state and local law enforcement officers, an incident that became

known as Bloody Sunday. Less than a year before Barbee filed the

Amos case, the bodies of slain civil rights activists James

Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were found in Mississippi.

In 1963 President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, and Medgar Evers,

NAACP leader in Jackson, Miss., was murdered. On Feb. 21, 1965, Malcolm

X, a man Barbee respected quite a bit, was murdered.31 In 1967, the urban riots that plagued other

major American cities in the mid-1960s came to Milwaukee. In 1968,

Robert F. Kennedy was killed in Los Angeles and Dr. Martin Luther King

Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tenn., Barbee's hometown.

Barbee received a full measure of threats and hate mail directed at

him and at his children - but he was determined to persevere, and he

soldiered on in spite of the danger. His daughter Daphne recalls that

the threats were frightening, but she also remembers her father saying,

"these threats are not going to stop me." Barbee believed that despite

the danger "if people want justice, they are going to have to keep on

fighting for justice."32

Trial of the Amos case finally began in late 1973 before

Judge Reynolds. MPS argued that Reynolds should make no changes in the

school system because MPS did not deliberately segregate students and

because integration would not improve the schooling black children

received. MPS also warned, prophetically, that desegregation could

trigger massive flight of white students to suburban school districts.

Barbee consistently argued that Reynolds's duty was to make a legal

decision, not a practical political decision, and that MPS could not get

around the central fact of the case: segregation violated black

students' right to equal protection of the law.

In 1976 Reynolds issued his decision.33

He agreed that MPS had not intentionally segregated Milwaukee schools

but he concluded that MPS had acted "with the full knowledge that racial

segregation existed ... and would continue to exist unless certain

policies were changed."34 Reynolds also

agreed with Barbee that the risk of white flight was not something he

should consider in making his decision. Reynolds explained that:

"The Constitution does not guarantee one a quality education; it

guarantees one an equal education, and the law in this country is that a

segregated education that is mandated by school authorities is

inherently unequal. ... If the law against intentional school

segregation is unworkable, then it should be repealed. Until then, it

must be obeyed."35

The months following the Amos decision were the pinnacle of

Barbee's civil rights career. Having attained a successful ruling,

Barbee was concerned that the legal victory would not be translated into

concrete change and improvement in the educational system. "The whole

system should be ordered to desegregate, root and branch," Barbee urged.

"If we don't do that, then we will have engaged in a paper

victory."36

Barbee worked with a chastened MPS to formulate a remedial plan. This

seems particularly indicative of Barbee's motivations, not merely to win

the case, but to help in crafting a solution. The plan finally approved

by Reynolds called for limited busing to achieve greater racial balance

in Milwaukee schools, funds for specialty schools to induce white

suburban students to transfer to MPS, and funds to help black students

adjust to suburban schools. Although the U.S. Supreme Court had recently

ruled in Milliken v. Bradley (1974) that suburban districts

could not be forced to participate in desegregation of urban

districts,37 Barbee and MPS persuaded many

Milwaukee suburban districts to join the plan. In mid-1976 Barbee had

the satisfaction of seeing his colleagues in the Legislature agree to

fund the plan.38 Barbee suffered a

temporary setback when the case was appealed and remanded for Reynolds

to reconsider his decision in light of recent school segregation

cases,39 but after doing so Reynolds

reaffirmed his order in 1978.40

Final Years: Steps Forward and Steps Backward

(1976-2002)

Barbee's triumph was not unalloyed. In the years after Amos,

white flight, the school choice program, and divisions in the black

community dealt setbacks to his vision of a fully integrated

society.41 In his later years, Barbee

acknowledged that the Milwaukee school system today is just as

segregated as it was in 1965. However, he argued that there is a

positive value in the fact that the segregation today does not have the

overt sanction of government that it had before Brown. Like the

Brown court, Barbee understood that government-sponsored

segregation inflicts its own kind of damage, stigmatizing certain

citizens merely on the basis of color and damaging their sense of self

worth and thereby denying the nation those citizens' full talents.

Barbee understood the self-destructive folly of such practices and

devoted his life to removing them from our educational system. Barbee

was the full embodiment and inheritor of the challenge laid down by the

NAACP's Charles Hamilton Houston, one of the principal architects of the

Brown victory:

"There come times when it is possible to forecast the results of a

contest, of a battle, of a lawsuit long before the final event has taken

place; and so far as our struggle for civil rights is concerned, the

struggle for civil rights in America is won. What I am more concerned

about is the fact that the Negro shall not be content simply with

demanding an equal share in the existing system. It seems to me that his

historical challenge is to make sure that the system which shall survive

in the United States of America shall be a system which guarantees

justice and freedom for everyone."42

In the Legislature and in the community, Barbee was often the only

voice for people or causes who had no other voice. In many circles he

was referred to as "the outrageous Mr. Barbee," a role used to challenge

the complacency of both blacks and whites. Like Houston, Lloyd Barbee

was a workhorse who dedicated his life to helping others, for little or

no pay, often so engrossed in his work that he forgot to eat.43 Barbee is truly an example of how much one

lawyer can accomplish when motivated by a passion to open the gates of

justice to the entire human race. As his son stated:

"The most important thing I learned from my dad was that we are all

only human beings - we are not black or white, ... this is our race and

our condition and if we only accept this, then we can move on to deal

with the human problems that we all face. ... This is who my dad was and

the legacy that we, all humans, must continue to struggle with."44

Barbee died at age 77 on Dec. 29, 2002, but his legacy has not been

lost:

"I am not discouraged. I have seen more difficult times. We are not

as well off as we could be, but we are better off than we were."45

Endnotes

1Lloyd Barbee Papers, Wisconsin

Black Historical Society and Museum.

2Gillespie v. Palmer, 20

Wis. 544 (1866); Joseph A. Ranney, Trusting Nothing to Providence: A

History of Wisconsin's Legal System 536-40 (1999); Leslie H.

Fishel, Wisconsin and Negro Suffrage, 46 Wis. Mag. Hist. 180

(Spring 1963).

3See Joe William Trotter

Jr., Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat,

1915-1945, at 103-08 (1985).

4Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

5Quinten Barbee, A Family

Remembers, Wis. Senior Advoc., Special Tribute Edition to Lloyd A.

Barbee, Sept. - Oct. 2003, at 6.

6Dr. Sean P. Keane, Struggle

for Liberation in Northern Ireland, Wis. Senior Advoc.,

supra note 5, at 20.

7Lloyd Barbee: I

Remember Milwaukee, 108 (WMVS/WMVT television broadcast, April 19,

1995).

8Interview with Daphne

Barbee-Wooten and Rustam Barbee, Feb. 5, 2004, at 18 (transcript on file

with Judge Maxine White).

9Id. at 40.

10Id. at 17.

11Lloyd Barbee: I

Remember Milwaukee, supra note 7, at 108.

12Id.

13The Legacy of Lloyd

Barbee, Wis. Senior Advoc., supra note 5, at 4.

14Id. at 15 (remarks of

J. Quinn Brisben).

15Barbee, Lloyd A., 1925-2002.

Papers, 1993-1982. U.W.-Milwaukee.

16See generally Taylor

Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years,

1954-1963 (1988).

17Jack Dougherty, More Than

One Struggle: The Evolution of Black School Reform in Milwaukee 76

(2004).

18Id. at 76, 80.

19Lloyd P. Jorgenson, The

Founding of Public Education in Wisconsin 15-22, 36-37 (1956);

Conrad E. Patzer, Public Education in Wisconsin 5-10, 348-63

(1924).

20Leonard Sykes Jr., Legacy of Brown Case a Mix of Hope, Frustration, Milw. J. Sentinel, Jan.

31, 2004.

21Frank A. Aukofer, City With

a Chance 35-39 (1968).

22Suburban Negro Ratio Lowest

in the Country, Milw. J., April 26, 1965.

23Dougherty, supra note

17, at 75; Taylor v. City of New Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181

(S.D.N.Y. 1961).

24See Wisconsin Blue

Book, 1965-66.

25Aukofer, supra note

21, at 50-55.

26Dougherty, supra note

17, at 71.

27Id. at 72-73.

28Dougherty, supra note

17, citing Milwaukee Star, Feb. 1, 1964.

29Ranney, supra note 2,

at 553-61; see also Amos v. Board of Sch. Dir. City of

Milwaukee, 408 F. Supp. 765, 792-93 (E.D. Wis. 1976).

30Interview with Daphne

Barbee-Wooten and Rustam Barbee, supra note 8, at 21.

31Id. at 9.

32Id. at 38.

33See supra note 29.

34Amos, 408 F. Supp. at

819.

35Id. at 821.

36The Legacy of Lloyd

Barbee, Wis. Senior Advoc., supra note 5, at 5.

37418 U.S. 717, 741-42

(1974).

38Laws of 1976, ch. 220.

39Armstrong v. Brennan,

539 F.2d 625 (7th Cir. 1976), rev'd, 433 U.S. 672 (1977),

on remand, 566 F.2d 1175 (7th Cir. 1977).

40Armstrong v.

O'Connell, 451 F. Supp. 817, 825, 866 (E.D. Wis. 1978).

41See Ranney,

supra note 2, at 553-61.

42The Road to Brown

(University of Virginia 1995).

43Interviews with Elizabeth Coggs

Jones, Lucinda Gordon, and Ann Tevik (transcripts on file with Judge

Maxine White); Wis. Senior Advoc., supra note 5, at 8, 9.

44Interview with Finn Barbee

(transcript on file with Judge Maxine White).

45Barbee, I Remember

Milwaukee, supra note 7, at 108.