Vol. 77, No. 5, May

2004

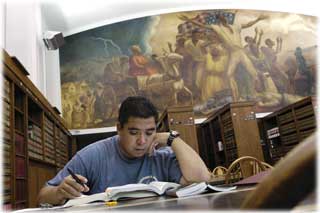

Chris Ochoa, IL

First-year U.W. Law School student Chris Ochoa brings a perspective

to his studies and life that few students and faculty share -- in 2001

he became the first prisoner exonerated by the Wisconsin Innocence

Project team. With almost a year of law school under his belt, Ochoa

works to reconcile the legal theory he's learning with his personal

experiences within the justice system.

by Dianne Molvig

|

|

|

Law student Chris Ochoa studies in the Quarles and Brady

Reading Room of the Law Library, beneath the 37-foot-long mural

Freeing of the Slaves , painted by John Stewart Curry from 1933

to 1942. Ochoa says the mural reminds him of the value of freedom.

Photo: Michael Forster Rothbart/UW-Madison University

communications

|

Most anyone who visits a prison finds the experience eerie, whether it's

noticing the razor-wire coils atop the perimeter fencing, or hearing the

emphatic clank of metal doors slamming behind you as you step inside

this world apart.

Prison sights and sounds may be especially chilling to Chris Ochoa, a

first-year law student at the University of Wisconsin Law School. After

all, he walked into a Texas prison on Nov. 11, 1988, at age 22, and he

didn't walk out again until 12 years and two months later.

Ochoa found himself back in a prison environment one day this past

January, this time at Fox Lake Correctional Institution, Fox Lake, Wis.

He was there to serve as a Spanish interpreter between an inmate and

students and faculty from the Criminal Appeals Project, one of the law

school's clinical programs.

Now that it's been three years since Ochoa regained his freedom, a

prison visit is perhaps "good therapy," he says. "Maybe that's part of

my wanting to be a lawyer - to work out whatever demons I have."

The latter process is ongoing, begun on Jan. 16, 2001, the day Ochoa

won release from prison, thanks to the efforts of law students from the

Wisconsin Innocence Project and its codirectors John Pray and Keith

Findley, who fought and won a 16-month battle to prove Ochoa had been

wrongly convicted of rape and murder. (See "Freeing the

Innocent," Wisconsin Lawyer, April 2001.)

After his release, Ochoa returned to El Paso, Texas, his hometown,

where he'd grown up in a working class family, the oldest of three sons.

Both his younger brothers now work as truck drivers. A local

construction company offered Ochoa his first post-prison job, apparently

more for the sake of its own publicity than truly to help him, as the

company laid him off soon after hiring him. He then worked at a couple

of different jobs, piled up credit card debt, and struggled financially

and emotionally.

"The hardest part," he recalls, "was trying to adjust, knowing that I

wasn't a 22-year-old anymore [he was then 34], but [wondering] how to

fit in with 30-year-olds? I didn't know where I fit in."

Ochoa enrolled in college to study business, which left him

uninspired, except for a business law class. That sparked the notion of

applying to law school. Further fueling that idea were his experiences

participating in a couple of wrongful conviction conferences at law

schools, and working with the attorneys representing him in his civil

suit against the city of Austin, Texas, for its police officers' actions

that led to Ochoa's wrongful conviction. "I was in on the initial

brainstorming [about the case]," he says. "The lawyers were asking me

for ideas. I felt real comfortable."

Another influence was, of course, his experience with the people at

the Wisconsin Innocence Project. Once Ochoa decided he wanted to study

law, he knew the U.W. Law School was his top choice.

The seeds of thinking about being a lawyer, however, go back even

further. In high school, Ochoa enjoyed his business law class and his

participation in a mock trial, in which, ironically, he acted as the

prosecuting attorney. Still, back then, "Coming from the background I

come from," he says, "I guess I never thought I had what it takes to go

to law school."

The Path to Prison

After finishing high school in El Paso, Ochoa moved to Austin to find

work and save money for college. He held various jobs, eventually

landing at a Pizza Hut, and then his life began to unravel.

Nancy DePriest, a manager at another area Pizza Hut, was raped and

murdered late one night at the restaurant. A couple of weeks later,

after Richard Danziger, Ochoa's 18-year-old roommate and coworker,

suggested they check out the crime scene, the two young men went to the

restaurant to ask a few questions. Call it youthful curiosity. But

Detective Hector Polanco viewed it as suspicious behavior; he brought

them into police headquarters for questioning.

What ensued was a living nightmare that even now, 16 years later,

Ochoa clearly dislikes discussing. Faced with Polanco's day-long

interrogation, Ochoa was barred from making any outside contact and saw

no lawyer. Polanco punctuated his questioning with loud, angry outbursts

and threats. He hammered repeatedly on the death penalty, pointing to

the very spot on Ochoa's arm where, after he'd been strapped down on a

gurney, the fatal injection would go.

After terrorizing Ochoa for hours on Friday, the police put him up in

a hotel for the weekend, supposedly "for his safety." Someone called

Ochoa's mother to inform her that her son would get the death penalty if

he didn't confess, which upset Ochoa even more than the threats Polanco

had hurled at him.

By Monday, police had Ochoa, who still hadn't seen a lawyer,

precisely where they wanted him. Polanco placed a confession in front of

him - in fact, the very same statement Polanco had tried to get two

other suspects to sign earlier, but the pair had solid alibis. "He just

whited out their names [and changed them]," Ochoa says. "That's how bad

it was." He signed the confession and also had to agree to testify

against Danziger.

"If you're not versed in the law," he points out, "what can you do?

Even if you are versed in the law, once the machine turns on you, you're

not going to beat it."

The machine to convict him then rolled into motion. Ochoa's

court-appointed attorney did nothing to build a defense. No one did even

basic investigating that would have cast doubts on the confession -

doubts quickly unearthed by law students and lawyers from the Wisconsin

Innocence Project.

For instance, Ochoa's confession stated he entered the Pizza Hut

through a locked door by using a key. But the door in question could be

opened only from the inside. "That detail right there," Ochoa notes,

"should have blown the confession out of the water." What's more, gaps

appeared on the tape of Ochoa's confession at points where police had

stopped and rewound the tape, coached Ochoa to tell the facts straight

(that is, their version of the facts), and then resumed taping.

Ochoa says the story of his coerced confession stirs a common

response from people who hear it: What if this happened to my son or

daughter? "Now I know why we have wrongful convictions," he says. "It's

easy to say, yeah, but you have to catch the bad guys. Well, what if the

government [wrongly] takes away somebody's son or daughter? That

shouldn't be. We criticize China and other countries for that. And we're

doing the same thing."

With no defense, Ochoa was found guilty and sentenced to life, as was

Danziger. "In prison," he says, "you lose track of time. You don't even

want to see a calendar, especially if you have a life sentence."

He knows he was one of the lucky ones. In 1996, Achim Marino, who was

in prison for other rapes, some of which occurred after DePriest's,

confessed to DePriest's rape and murder. Still, prosecutors and police

held onto the belief that Ochoa also had been involved. Three years

later, police showed up at prison to ask Ochoa more questions about the

crime, without telling him about Marino's confession.

Ochoa knew something was going on. He found an address for the

Wisconsin Innocence Project and sent an eight-page letter asking that it

investigate. "My biggest worry," he says, "was that the guards or warden

would tear up my letters." Eventually, DNA evidence confirmed Marino was

the rapist, and Ochoa and Danziger again became free men.

Life as a Law Student

Given his experiences, Ochoa has a unique perspective on the rigors

he faces as a first-year law student. "It's difficult," he says, in his

typically quiet manner, "but I've adapted to worse situations than law

school."

Still, he admits sometimes it's hard for him to witness what goes on

in law school. "I see people who are so naive, but it's not their

fault," he says, possibly thinking of his own naiveté at age 22,

when, until he faced police interrogation, he'd believed nothing bad

could happen to an innocent person.

The toughest part of his first semester was his introductory criminal

law class. "I struggled with the concepts of law, the theoretical," he

says. "It doesn't match with the reality of the law and the way it

works." One of Ochoa's attorneys for his civil suit pointed out why he

had reason to be upset.

"He told me you're studying the stage that sent you up the river,"

Ochoa says. "There was a confession, some pieces of circumstantial

evidence. That met the elements." And it was all it took for prosecutors

to win Ochoa's conviction.

He knows there will be opportunities in future courses to explore

cases from the defense viewpoint and learn about prosecutorial failings.

"The problem is you're shaping minds in that first year," he says. "We

should be showing them there are two sides to a case. That's a big

problem because unless law schools start changing, it will be a

never-ending cycle."

Now in his second semester, Ochoa says he feels he has a better

handle on some of his frustrations, reminding himself, "I'm not here to

teach," he says. "I'm here to learn."

He's also thankful to have behind him a major distraction that

haunted him throughout his first semester: his long, drawn-out civil

action against Austin, Texas, for its police officers' actions that led

to Ochoa's wrongful conviction. The civil suit required him to make

several trips back there last semester, devouring time, but also

stirring old emotions as the case delved into where the fault lay for

the wrongful conviction.

"At one point," he recalls, "I said to my lawyers, 'What the hell is

going on? The DA is blaming me, the cops are saying it was my fault.

Everybody says it's my fault.'" The experience was, perhaps, like being

back in Polanco's interrogation room all over again.

Besides the numerous trips to Austin last semester, Ochoa also flew

back to El Paso for his godmother's funeral. Not everyone could

understand why it was so important to him to do that, in light of the

demands law school and his civil suit were putting on him. To Ochoa, it

was clear why he had to go. "I missed my grandfather's funeral [while

Ochoa was in prison]," he says. "I didn't feel I could do that again. I

just couldn't do it."

Ochoa had been extremely close to his grandfather all through his

youth. "He was my best friend," he says. And he remained so while Ochoa

was in prison. Every month, he sent his grandson $15, and he tried to

make the 10-hour trip from El Paso to the prison once a year or so. He

mailed Ochoa the El Paso newspaper, wrote a letter every week, and

instructed family members that his grandson was to receive part of his

modest inheritance, just like everyone else.

"He stuck by me," Ochoa says. "When you have a family member you're

so close to, come hell or high water, you're going to get to the

funeral." Only prison could, and did, stop him.

Shortly after getting out of prison, he stood at his grandfather's

gravesite. It was one of the few occasions when he allowed himself to

feel his rage against Polanco. "I looked at my grandfather's grave, and

I looked at my mom, who was in tears," he recalls, "and I said, 'Look at

what this cop left me. A grave.'"

The Missing Pieces

Finally, toward the end of last semester, the Austin city council

voted in favor of the settlement in the civil suit. While awaiting the

results on the day of the vote, Ochoa was tense and couldn't concentrate

on his studies. He told a fellow 1L that instead of going to contracts

class, he needed to go to lunch and have a beer. His classmate joined

him.

"They say when you go to law school, you'll make one or two lifetime

friends," Ochoa says. "I think I've made that friend."

The $5.3 million settlement, set up to provide Ochoa monthly payments

for the rest of his life, assures his financial security. He's also

aware of what the settlement can't do for him. A 12-year hole in his

life remains.

"The object of a civil suit," says Ochoa, now 37, "is to put the

person back in the place he would have been if that injury had not

happened. They can't ever do that. They can't bring the wife I might

have had, the kids." He worries that some things in life have passed him

by and never will happen.

As for the people responsible for his wrongful conviction, Polanco

never apologized to Ochoa and has retired from the police force. At the

hearing at which Ochoa was released from prison, the original prosecutor

on his case sat in the courtroom, glaring at him. Afterward, she warned

Ochoa that he'd better not try to blame the police officers.

And his original defense attorney? Missing in action, just as he was

back in 1988 when he was supposed to have defended Ochoa. That attorney

showed his lack of character again in 1999 when the Wisconsin Innocence

Project contacted him. He said, yes, he remembered Ochoa's case, and

they were wasting their time because Ochoa was guilty. Did they know

about the evidence of the gun, the murder weapon, with Ochoa's

fingerprints on it? The Innocence Project almost dropped the case at

that point. But fortunately, they checked into it, finding that no such

gun existed, and that the lawyer was lying to cover himself.

Meanwhile, Ochoa continues the process of putting his life back

together. He was pleased to be elected this semester as the community

vice president of the Latino Law Student Association. And this summer

he'll begin the year-long Innocence Project clinical course, as he

continues to explore what type of law he might practice some day.

Does he feel he's gotten back to being his old self? "There's a long

way to go," he responds. "Law school is helping me a lot - being on my

own, being more mature. I'm starting to see that society is not all that

bad. I'm getting back to what you'd call normal, I guess."

Learning to trust others again, however, may take a bit longer.

"That's the tough one," Ochoa says. "But eventually, I will."

Dianne Molvig operates

Access Information Service, a Madison research, writing, and editing

service. She is a frequent contributor to area publications.

Wisconsin

Lawyer