Attorney Joe is assigned to represent Petitioner Jake in an appeal of a misdemeanor conviction. While reviewing the record, Joe learns that Jake apparently was struggling during the trial court’s proceedings: he seemed to have a hard time following basic instructions; he tried to contact the trial judge directly despite repeated reprimands; and he frequently lost his place in conversations, repeating information without apparently remembering that he had already done so. When asked about his experience, Jake admits that he sometimes doesn’t feel “all there” and that it can be hard for him to pay attention, particularly when he’s stressed, challenges that he attributes to concussions he suffered as a high-school athlete.

As Joe and Jake begin to work together, Joe quickly observes the same interpersonal challenges – problems following instructions, remembering information, and holding conversations – that were noted in Jake’s record. Joe does what he can to help Jake through the appeals process, but Jake continues to struggle in his interactions with Joe and with other legal officers and is often frustrated by the demands of his case. “It’s just a lot to deal with,” he tells Joe at one point. “I feel like I never really know what’s going on.”1

Jake’s situation is not unique; in fact, it’s commonplace. A staggering percentage of people who are defendants in criminal legal proceedings – at least one-half by realistic estimates, although some studies have found percentages close to 100%2 – experience cognitive-behavioral limitations in fundamental human actions such as thinking, remembering, communicating, and planning. These limitations, or neurodisabilities, can dramatically affect how a person performs day-to-day activities. Whether it is difficulty staying on task, adapting to new behavioral expectations, or maintaining a coherent conversation, neurodisabilities can create steep hurdles in a person’s family, work, or social life.

As Jake’s example shows, legal contexts are no different, and neurodisabilities can present serious challenges not only for many clients, defendants, and petitioners but also for lawyers and judges.

To help legal professionals recognize and accommodate neurodisability in their work, this article summarizes current definitional models of neurodisability, discusses behavioral challenges typically associated with neurodisability, and defines neurobiological conditions that frequently underlie neurodisability. The article illustrates how neurodisability might present in terms of behaviors or actions and how legal professionals might address and accommodate those behaviors within their practices. This article’s brief overview should help legal professionals be more informed, more effective, and ultimately more empathetic when interacting with persons with cognitive-behavioral challenges.

Defining Neurodisability

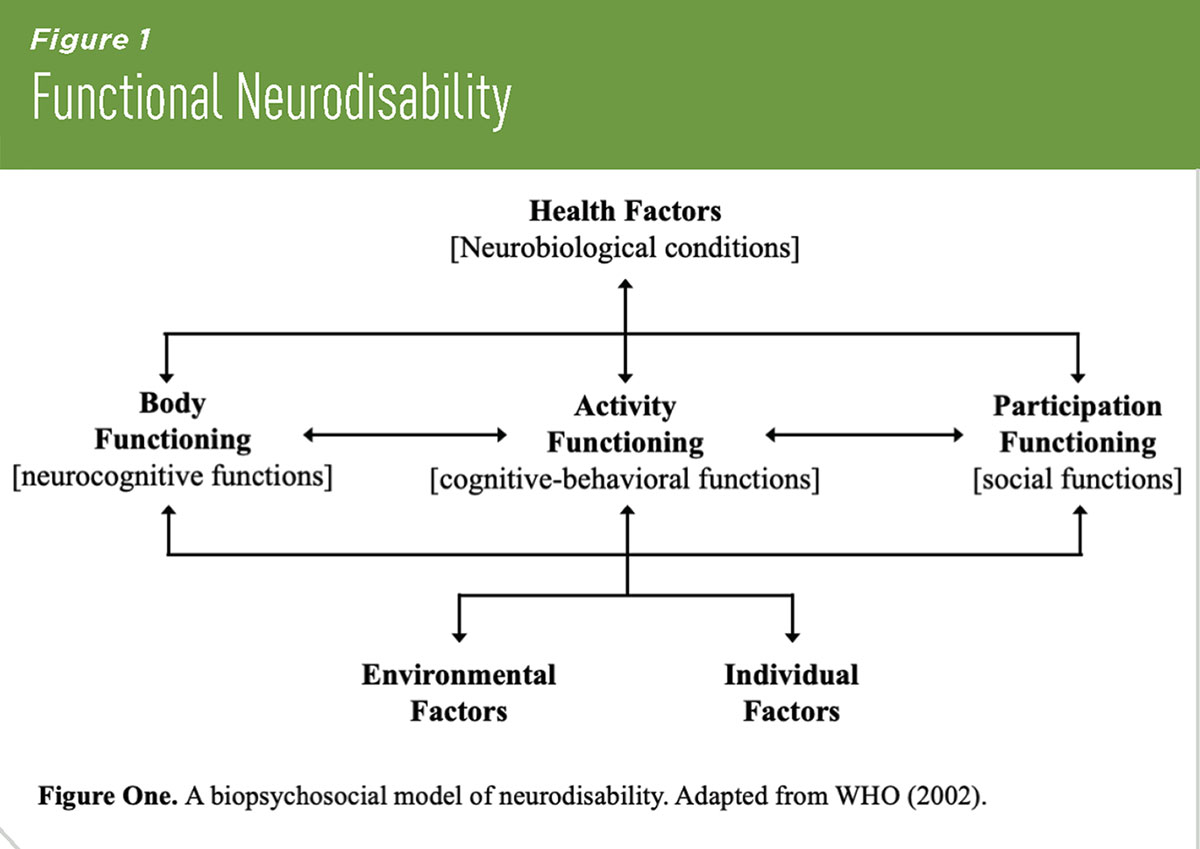

Despite their potential complexity and severity, neurodisabilities have a straightforward definition: they are functional limitations that arise from the interaction of a person’s (neuro)biological, individual, and environmental factors.3 Figure One: Functional Neurodisability shows how prevailing models of neurodisability illustrate these functional limitations:4 a person’s (neuro)biological, individual, and environmental factors influence, and are influenced by, functions at three interconnected levels (the person’s physical body, the person’s cognitive-behavioral activities, and the person’s social participation). Effectively, neurodisability manifests when any of the person’s biopsychosocial factors limit any of their cognitive-behavioral participation. This means that neurodisabilities always exist within the person’s contextual circumstances and always reflect a spectrum of functional limitation.

Joseph A. Wszalek, JD, PhD, is a neuroscientist and neuroethicist who earned his law degree (U.W. 2015, cum laude, Order of the Coif) through an interdisciplinary training program in neuroscience and public policy. An expert in brain injury, language and communication, and cognitive neuroscience, his research and work focus on the interaction between the law and human social behavior. He has presented his scholarship to professional groups, governmental organizations, and academic conferences throughout the world.

Joseph A. Wszalek, JD, PhD, is a neuroscientist and neuroethicist who earned his law degree (U.W. 2015, cum laude, Order of the Coif) through an interdisciplinary training program in neuroscience and public policy. An expert in brain injury, language and communication, and cognitive neuroscience, his research and work focus on the interaction between the law and human social behavior. He has presented his scholarship to professional groups, governmental organizations, and academic conferences throughout the world.

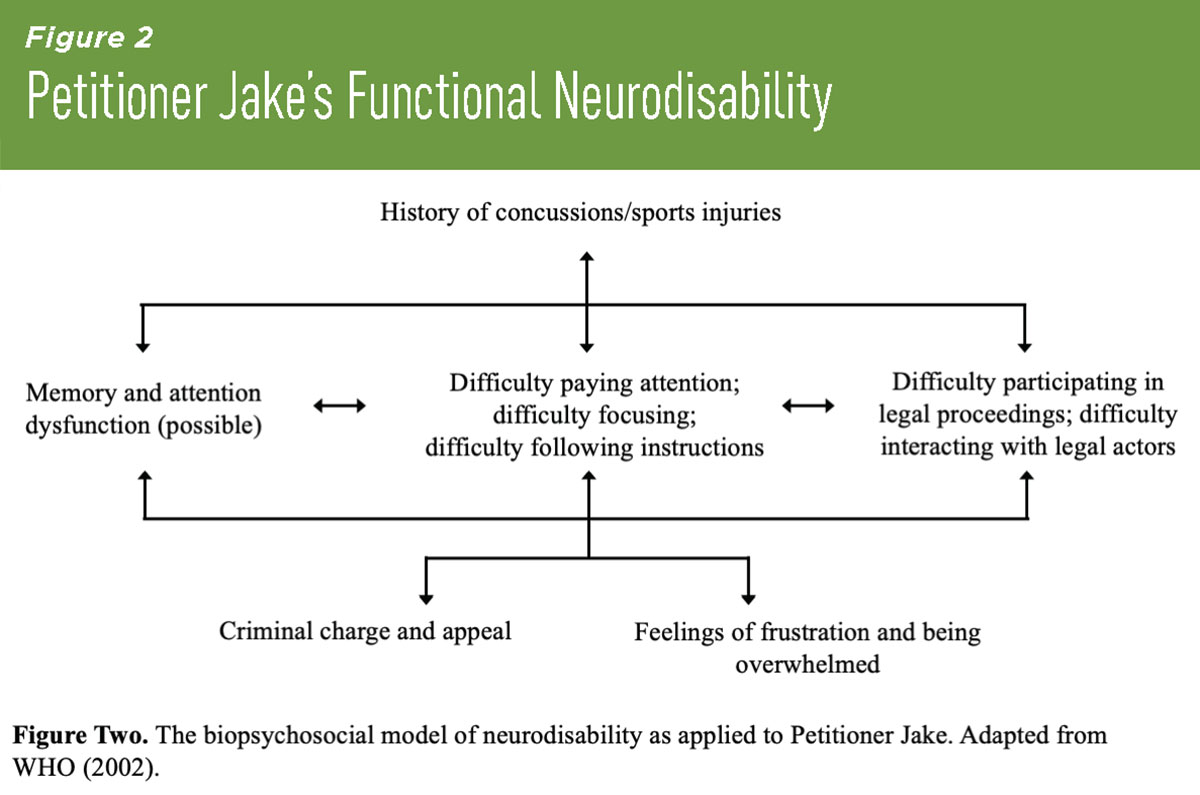

Consider Petitioner Jake’s behavior in terms of this model of neurodisability (see Figure Two: Petitioner Jake’s Functional Neurodisability). We can see that Jake’s cognitive-behavioral struggles reflect a spectrum of interconnected functional limitations. Jake has difficulty following instructions, remembering information, and holding conversations. This likely reflects functional limitations at the level of cognitive-behavioral activity, that is, the level of functioning at which Jake performs specific cognitive-behavioral tasks like working memory integration, behavioral planning, and narrative language structuring.

Similarly, Jake has difficulty focusing and paying attention. In addition to limitations at the level of cognitive-behavioral activity, this could reflect functional limitations at the level of neurobiological function, that is, the level of functioning at which Jake’s brain and nervous system work.

Finally, Jake has difficulty interacting with legal actors and navigating the behavioral expectations of the legal context. This reflects functional limitations at the level of social participation, that is, the level of functioning at which Jake interacts with the social world around him.

Next, consider how Jake’s circumstances fit within the model. Jake has a self-reported history of concussions, which may be a factor in his neurobiological condition. Jake is experiencing feelings of frustration and being overwhelmed (in addition to probably being stressed), which will all factor into his personal circumstances. Finally, Jake is trying to get an appeal of his misdemeanor conviction, so he faces whatever external pressures (time, stress, legal risks, legal status, and so on) arise from that process as environmental factors.

In summary, Jake’s cognitive-behavioral struggles are not only a spectrum of interconnected functional limitations but a spectrum of interconnected functional limitations that arise from his personal, contextual, and environmental circumstances. It is through this interplay between functional cognitive-behavioral limitations and contextual factors that Jake experiences his neurodisability.

One aspect of this definition of neurodisability merits additional mention here. Neurodisability is a descriptive term, not a prescriptive term. It describes cognitive-behavioral activities that are functionally limited and the circumstances under which that limitation occurs, but it does not categorically dictate a person’s cognitive-behavioral ability. Put another way, neurodisability describes which actions are harder to perform and which factors contribute to that difficulty, but it does not dictate what a person “can” or “should” be able to do. Scientists represent this distinction by saying that neurodisability is a state, not a trait: it is a status that a person experiences, not an attribute that they possess.

Apply this nuance to Petitioner Jake. He might experience a broad set of functional limitations in his thinking, communicating, and planning and might experience overall lower quality participation in his legal matter, but that doesn’t necessarily mean he categorically can’t do those things or physically can’t navigate the legal situation around him. Will certain situations increase the likelihood of limitations? Almost certainly – Jake admits that being stressed makes it harder for him to pay attention. Will Jake always experience some degree of cognitive-behavioral limitations in certain activities, even under ideal situations? Possibly – Jake admits that feeling “not all there” is an ongoing experience for him.

But the important point is that the degree to which Jake experiences functional limitations will not be constant. As a result, Jake’s neurodisability is an objective assessment of his cognitive-behavioral limitations, not a blanket conclusion about his overall cognitive-behavioral capabilities.

To summarize, neurodisability indicates limitations across a continuum of functional behaviors that arises from the interaction between person and environment. The key takeaway is that neurodisability is a matter of functional limitation. What ultimately matters is whether a person can do what they want to do or what they’re trying to do under the circumstances – individual, biological, and environmental – in which they’re acting.

Recognizing Neurodisability

Recognizing neurodisability can be a challenge in and of itself. Lawyers and judges who work in criminal law can reasonably expect that a high percentage of the clients and parties they encounter will experience some sort of functional cognitive-behavioral limitation. But unlike Petitioner Jake, not every party or client will have the ability or the opportunity to articulate cognitive-behavioral limitations and the conditions under which they are likely to occur, and not every party or client will be willing or able to divulge (neuro)biological conditions that can give rise to functional limitations. As a result, lawyers and judges will probably need to be more proactive in recognizing behaviors and conditions associated with neurodisability.

To make recognition more difficult, functional cognitive-behavioral limitations frequently present as – and are frequently misinterpreted as – intentional attitudes or behaviors or character traits, and this presentation can complicate the way in which people interact with and respond to persons who experience neurodisability.

Consider Petitioner Jake’s example. His behavioral struggles – following instructions, holding onto information, and keeping track of conversations – may all appear to be very similar to the behaviors of a person who intentionally disregards instructions, doesn’t pay attention, or has a confrontational attitude, but they have radically different substantive and procedural implications and require radically different interpretations and responses.

Thus, effective legal work means being able to proactively recognize and accurately interpret cognitive-behavioral limitations.

Functional Cognitive-Behavioral Limitations

Table One shows behaviors typically associated with neurodisability.5 For each behavior, consider three pieces of information: 1) what the behaviors might present as and how you might “incorrectly” interpret them, 2) what the behaviors might be in terms of cognitive-behavioral limitations and how you might “correctly” interpret them, and 3) which cognitive-behavioral impairments or dysfunctions might underlie the behavior. Keep in mind that these are descriptive, not prescriptive, assessments: your focus should be on recognizing and interpreting cognitive-behavioral limitations and considering how those limitations might affect the person’s ability to work with you or to navigate their legal matter.

Two aspects of Table One’s behavioral limitations are particularly significant. First, these behaviors are associated with neuropsychological and neurobiological conditions that are overrepresented in people in the criminal legal system. For example, limitations in attention, memory, and impaired communication are common consequences of brain injuries, and limitations in behavior regulation are common consequences of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (see “Conditions Associated with Neurodisability” below). Second, these behaviors tend to be associated with multiple neuropsychological and neurobiological conditions. For example, inappropriate social behaviors and limitations in attention and memory are common consequences of many conditions that affect the brain. Regardless, every behavior on the list can ultimately affect activities such as preparing and giving testimony and making decisions about legal goals, so they are important cognitive-behavioral limitations to recognize.

One final important distinction in recognizing neurodisability is the distinction between intent and ability (or “will” versus “skill”). As briefly discussed at the beginning of this section, behaviors and behavioral limitations associated with neurodisability can present as an intentional attitude or behavior or a character or personality trait. For example, Petitioner Jake’s repeated ex partecommunication might present as and initially be interpreted as a cavalier attitude, a conscious effort to disregard court protocol, or irresponsible conduct (or some combination of all three) – it is a common human tendency to attribute someone’s behavior to their personality or intentional choices.6

For neurodisabilities and functional cognitive-behavioral limitations, however, the behaviors might more accurately reflect functional limitations independent of intention. Jake might not have learned what the concept of ex partecommunication means, or he might have learned it but forgotten with each warning, or he might have been acting under an incorrect understanding (explanations that would all be consistent with academic scholarship on the relationship between neurodisability and legal knowledge7). It also is possible that his breaches of protocol were done entirely in good faith and with the intent to meaningfully participate in his own proceedings.

None of this is to say that neurodisability precludes intentional action or attitude. Jake might have hated every minute of his interaction with the legal actors in his case, and he might not have cared about the court’s rules at all, but he would have nonetheless done so within the context of functional cognitive limitations that could have hindered his ability to learn, retain, and apply information. Neurodisability can limit a person’s behavior regardless of what they want to do or how they want to act, so recognizing neurodisability includes appreciating the distinction between intent and ability.

Table 1: Neurodisability and Legally Relevant Behaviors

Conditions Associated with Neurodisability

An important aspect of recognizing neurodisability is being aware of neurobiological conditions associated with functional cognitive-behavioral limitations. As stated above, (neuro)biological conditions are one of the factors through which a person can experience functional limitations: Although these conditions do not per se equate to neurodisability (because neurodisability is a descriptive functional assessment), they may cause cognitive-behavioral impairments that increase the risk of functional limitation.

The following conditions are common causes of cognitive impairments and are thus commonly associated with neurodisability. Note also that these conditions are overrepresented in criminal legal systems, meaning that rates are higher for persons in criminal legal systems than for the overall population.

Brain Injury. Brain injuries occur through physical trauma (for example, a car crash or a fall) or through illness (for example, a stroke). Brain injuries cause complex changes to overall brain function; typical impairments include executive dysfunction (for example, reasoning limitations, decision-making limitations), memory limitations, and social-behavioral limitations (for example, inappropriate communication). Estimates suggest half of all the individuals in criminal legal systems have a history of brain injury, but rates as high as 100% have been reported.8

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). FASD is a neurobehavioral disorder caused by prenatal alcohol exposure. FASD can cause complex changes to overall brain function; typical cognitive impairments include problems with behavioral and emotional regulation (for example, anger management problems), memory limitations, and limitations in processing different types of information. Estimates suggest between one-quarter and one-third of all persons in criminal legal systems meet the criteria for FASD.9

Intellectual Disability. Intellectual disability encompasses developmental disorders that lead to lower-than-average or below-average intellectual functioning, stereotypically categorized as “low IQ.” Like brain injuries and FASD, an intellectual disability can cause complex changes to overall brain function; typical impairments include limitations in abstract thinking, language and communication, and executive functions (for example, reasoning and decision-making). Estimates suggest around 40% of persons in criminal legal systems meet the criteria for an intellectual disability.10

To summarize recognizing neurodisability, neurodisability in the law often manifests as a set of behavioral limitations, and neurobiological conditions might underlie these behaviors. Recognizing and interpreting neurodisability means understanding how neurodisabilities present, interpreting what those behaviors might mean for the client or legal party’s ability to navigate their legal matter, and then responding appropriately.

Accommodating Neurodisability

Accommodating neurodisability can be an even greater challenge than recognizing it. Cognitive impairments can lead to complex behavioral challenges that are difficult, if not impossible, to manage, even in formal therapeutic or rehabilitative settings. In addition, cognitive impairments are often “invisible”: a client’s physical limitations such as mobility issues or a speech impediment are usually readily apparent to other people, but cognitive-behavioral limitations are not. Fortunately, (neuro)biological conditions are only one factor in neurodisability, so legal actors’ goals are relatively straightforward: accommodate the functional limitations as much as possible. By controlling or modifying contextual or environmental factors within legal settings, legal actors can lessen the effect that functional limitations have on legally relevant activities and legal participation.

Individual Accommodations. The following accommodations are generally good practices for working with persons experiencing neurodisability. Each focuses primarily on the “environment” factor of the neurodisability model; that is, they will reduce the contextual hurdles that the person experiencing neurodisability needs to overcome. Remember, neurodisability is a state, not a trait – functional limitations occur within a set of individual, biological, and environmental circumstances, so even though you won’t be able to “fix” a person’s individual or (neuro) biological circumstances, you will be able to create a legal environment that facilitates smoother behaviors and activities.

• Scaffold. “Scaffolding” is a communication support strategy in which you provide information or guidance on which the person experiencing neurodisability can “build” their communication or knowledge. Note that scaffolding might be particularly helpful for a person exhibiting lack of attention or focus or having difficulty following along with a conversation. Accommodations might include the following:

Have the person fill in blanks or complete sentences to assess understanding.

Example: Attorney can help Client understand the term of an agreement by asking, “If you take this deal, you’re going to have to give up your right to do what?”

Provide prompts to help a person ask questions or provide a narrative.

Example: Attorney prompts Client during a hearing, “Wasn’t there something you needed to say about your last day of work?”

Give notes or aids, or let the person take notes or use aids.

Example: Judge says to Client, “This piece of the paper will tell you what the ex parte rules are. If you can’t remember or forget, just look at paper.”

• Reduce external stimuli. Reducing external stimuli means minimizing distractors or stressors (for example, noise, time pressure, other people) that might confuse or hinder a person experiencing neurodisability. Reducing external stimuli might be particularly helpful for persons exhibiting avoidance behaviors or socially inappropriate or impulsive communication. Accommodations might include the following:

Offer the person a short break to decompress during conversations.

Example: During a long hearing, Attorney says, “We’ve been talking for a while, Judge. Can we take a 10-minute break so my client can take a breather and recharge his batteries?”

Keep the physical space as tranquil as possible.

Example: Judge moves the parties into a quieter room and turns off some of the harsh florescent lights.

Model nonconfrontational behavior.

Example: In response to Client expressing or showing frustration, Attorney keeps a calm tone and offers professional and personal empathy.

• Allow a communication partner. Many people with cognitive-behavioral limitations have support persons (family members, close friends, and so on) who help them navigate their social interactions. If possible, allow the client or party to work alongside their communication partner when they interact with you. Accommodations include the following:

Give the person opportunity to consult with a communication partner.

Example: Attorney and Judge say to Client, “Taking this settlement offer is a big decision. Why don’t you discuss it with your friend before we go any further?”

Have the communication partner take a more active role in the activity.

Example: Attorney says to Client, “I’m going to ask your friend to read you some questions for me. Just answer them as best you can, ok?”

Ask the communication partner for tips or advice.

Example: Judge says to Client, “Your friend said that you have an easier time when things are written down. I’m going to give you a written copy of what I’m going to say before I start.”

These accommodations aren’t always practical or possible, and some of them aren’t consistent with typical legal practices and courtroom procedures. But this leads to one of the most important accommodations you can offer: Be honest and open about what the person experiencing neurodisablity can expect within the law. Tell them that courts don’t have much time or money to spare. Tell them that legal professionals typically don’t get much training in working with persons with cognitive-behavioral limitations and that areas of law like criminal procedure and appellate procedure are difficult for everyone involved. Helping set realistic expectations might not do much for functional cognitive limitations, but it can go a long way toward helping people (with or without neurodisability) feel more empowered and better use their voice and choice. In other words, setting realistic expectations can help moderate some individual factors that might have contributed to functional limitations.

Systemic Responses to Neurodisability

Some readers might have looked at this article’s definitions and approaches to neurodisability and realized that the analysis has quite broad implications. They might think the following: “Hang on. If neurodisability represents limitations based on a combination of biological, individual, and environmental factors, doesn’t that mean that pretty much anybody could experience a neurodisability? I get stressed by my work all the time, I’ve got a packed work load and calendar, and there are times when it feels like I have a hard time staying on top of everything mentally and knowing what’s going on. How on earth am I supposed to recognize or accommodate neurodisability when functional limitations could be happening to anyone any time they’re in my office or court?”

These are good questions. It probably will be difficult for most lawyers to recognize and accommodate functional cognitive-behavioral limitations, and one of the reasons is that the legal system wasn’t set up to recognize or accommodate neurodisability. United States (common) law by design defines human behavior through abstracted, artificial a priori standards,11 and even modern legal practices such as competency-to-plead assessments are ultimately based on the judges’ and lawyers’ overall impressions. This is to say nothing of the role that elements of the law and legal procedures themselves such as legalese language and adversarial dispute resolutions play in making cognitive-behavioral tasks more difficult.12 So if you ask, “How am I supposed to recognize and accommodate neurodisability,” the honest answer is, “You’re not really supposed to.” This doesn’t mean lawyers shouldn’t try to provide the individual accommodations listed above, but lawyers owe it to clients and parties (and to themselves) to be honest about how the law works at a structural level.

That said, there are two guaranteed ways to accommodate persons experiencing neurodisabilities and to minimize the risks of limited participation: keep people out of the system in the first place and change how the system works. I conclude this article by briefly discussing a few ideas that are gaining ground among scholars and advocates who are trying to reimagine the way in which the U.S. legal system works.

Focus on Earlier Intercepts. “Intercepts,” or points of contact between an individual and the (criminal) legal system, are interactions or situations in which individuals might be diverted from traditional criminal justice pathways. So-called intercept models were created in explicit response to overrepresentation of persons with mental illness within criminal legal systems, and the overall goal is to prioritize community services over carceral response.13 Strategies include keeping people in school or work, using specially trained responders instead of regular law enforcement, and expanding the reach of public services such as health care. Note that proactive fields of law such as preventative law focus on these exact intercepts and strategies, so they should offer good resources for practitioners who are trying to keep parties and clients from coming into contact with the law in the first place.

Develop Alternative Legal Frameworks. Alternative legal frameworks (for example, therapeutic jurisprudence) present different dynamics among the system, legal actors, and parties and clients. These frameworks can be useful tools for analyzing the law’s relationship to complex biopsychosocial phenomena such as neurodisability and for proposing new legal solutions.14 Approaches include developing legal venues or procedures specifically designed to accommodate certain groups (for example, courts for persons with disabilities) and creating alternative theoretical justifications for legal power and legal authority. The law itself is an unavoidable factor in functional limitations, so addressing systemic risk factors means changing the system itself.

Conclusion

People like Petitioner Jake face criminal, civil, or administrative legal procedures every day, and without accommodations, they face a real likelihood of compromised participation, poor outcomes, and negative perceptions. Fortunately, current models of neurodisability offer a usable framework for defining, recognizing, and accommodating cognitive-behavioral limitations. Understanding that neurodisability is a functional limitation caused by multiple factors can help legal actors approach their clients’ or parties’ behavior from a biopsychosocial perspective and can help legal actors appreciate the relationships among (neuro)biological conditions, behavior, and legal participation. Some factors underlying neurodisability will always be beyond the control of legal actors, but lawyers bear the onus of making sure that the environment in which they practice – and their own ability to recognize and accommodate neurodisability – are consistent with a descriptive, holistic framework of functional cognitive-behavior.

Also of Interest

Learn More About Assisting Clients with Mental Illnesses or Neurodisabilities

Mental Health Law in Wisconsin: A Guide for Legal and Healthcare Professionals, published by State Bar of Wisconsin PINNACLE®, can help you better prepare to advocate for clients.

People with neurodisabilities interact with the legal system in a variety of ways – criminal cases, civil rights actions, family law disputes, cases involving older adults, and in the corporate arena. The Guide helps attorneys in government or private practice, their staff members, and judges and court commissioners understand how the law defines mental health and be better prepared to advocate for and accommodate clients and parties.

Mental Health Law in Wisconsin: A Guide for Legal and Healthcare Professionals, available in print and online through Books UnBound, clarifies topics that are frequently misunderstood, especially within the context of the legal system. From how the courts define “mental illness” to understanding the effect trauma has on mental health and knowing the rights and responsibilities of all parties involved, the book provides a comprehensive, straightforward overview of how mental health issues and the law intersect.

Click here to learn more and to purchase

Endnotes

1 This scenario is based on a composite of actual events, with names and circumstances altered for anonymity and for illustrative effect.

2 There are many scientific studies on the prevalence of neurodisabilities within the criminal legal system, see infra notes 7-9, but this commissioned assessment of the New Zealand legal system is an excellent summary of the many issues at play. Ian Lambie, What Were They Thinking? A Discussion Paper on Brain and Behavior in Relation to the Justice System in New Zealand (2020), https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2022-04/PMCSA-20-02_What-were-they-thinking-A-discussion-paper-on-brain-and-behaviour.pdf.

3 See, e.g., Sandra Neumann et al., Quality of Life in Adults with Neurogenic Speech-Language-Communication Difficulties: A Systematic Review of Existing Measures., 79 J. Commun. Disorders 24 (2019).

4 World Health Org., Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health 22 (2002), https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/classification/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf.

5 Lambie, supra note 2.

6 See, e.g., Fundamental Attribution Error, Wikipedia,https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamental_attribution_error (last visited Nov. 2, 2023).

7 Michele LaVigne & Gregory J. Van Rybroek, “He Got in My Face so I Shot Him:” How Defendants’ Language Impairments Impair Attorney-Client Relationships, 17 CUNY L. Rev. 69 (2014); Joseph A. Wszalek & Lyn S. Turkstra, Language Impairments in Youths with Traumatic Brain Injury: Implications for Participation in Criminal Proceedings, 30 J. Head Trauma Rehabilitation 86 (2015).

8 See, e.g., T. J. Farrer & D. W. Hedges, Prevalence of Traumatic Brain Injury in Incarcerated Groups Compared to the General Population: A Meta-Analysis, 35 Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biology Psychiatry 390 (2011).

9 See, e.g., Svetlana Popova et al., Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Prevalence Estimates in Correctional Systems: A Systematic Literature Review., 102 Can. J. Pub. Health 336 (2011).

10 See, e.g., Seena Fazel, Kiriakos Xenitidis & John Powell, The Prevalence of Intellectual Disabilities among 12,000 Prisoners - a Systematic Review, 31 Int’l J. L. Psychiatry369 (2008).

11 Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., The Common Law (Paulo Pereira J.S. & Diego M. Beltran eds., 2011).

12 Joseph A. Wszalek, Cognitive Communication and the Law: A Model for Systemic Risks and Systemic Interventions, 8 J. L. & Biosciences 1 (2021).

13 See, e.g., Lindsay Lawer Shea, Dylan Cooper & Amy Blank Wilson, Preventing and Improving Interactions between Autistic Individuals and the Criminal Justice System: A Roadmap for Research.

14 See, e.g., Michael L. Perlin, “I Hope the Final Judgment’s Fair”: Alternative Jurisprudences, Legal Decision-Making, and Justice, in The Cambridge Handbook of Psychology of Legal Decision-Making (2022).

» Cite this article: 96 Wis. Law. 16-24 (December 2023).