Vol. 75, No. 10, October

2002

Is it Time to Hire an Administrator?

Not every firm may need or want a legal administrator. But what are

some of the signals that it might be time to consider hiring one?

Lagging behind in your accounts receivable, high nonlegal staff

turnover, and unproductive staff could be indicators. Or maybe you're

spending too much time performing administrative tasks yourself and not

enough time practicing law. Read what prompted some firms to hire an

administrator and what tasks those administrators are performing.

by Dianne Molvig

by Dianne Molvig

You're a partner in a small law firm, and with each passing year the

demands on your time multiply. Not only do you have clients to keep

happy, but you face endless other tasks related to running your

practice: managing finances, hiring staff, buying technology upgrades,

monitoring insurance policies, ordering new office furniture, finding a

contractor to repair the roof ... the list goes on.

These responsibilities can devour hours of your day, all unbillable.

Something has to give, you tell yourself. But what? Sure, you have staff

to help out, but there's a limit to how much they can do - and how much

you're willing to entrust to them. Some administrative matters only you

and your partners can handle, in your view. After all, your names are on

the office door.

Still, one thought keeps nagging at you: Why am I spending so much of

my time in the office doing everything but practicing law?

That's a question attorney Bob Kohn of Kohn Law Firm, Milwaukee,

grappled with some years ago when he was still a sole practitioner. "As

the practice grew, I was doing more and more nonlawyer work," he

recalls. "I was a jack-of-all-trades."

Eventually, Kohn decided he had to find another way to operate. "If

you're going to grow and prosper in this business," he says, "you can't

run the show yourself. You can't be hands-on forever. I was a hands-on

guy. I started that way, and it took me a while to get out of that

mode."

Today, he readily unloads administrative duties onto Brenda Majewski,

his firm's administrator. "I put a lot of responsibility on her

shoulders," he notes, "and rightly so. That's where it should be. I

don't want to run the office. I don't want to be the human resources

guy. I don't want to be the one who manages the bills and finances. I

want to practice law."

Shifting the Burden

Kohn is among a growing number of Wisconsin lawyers who have opted to

ease their time constraints by adding a legal administrator to their

staff. What exactly does a legal administrator do? The nature of the job

varies somewhat from one firm to another. Broadly defined, however, a

legal administrator is a person who is "responsible for nonlegal

administration of the organization," according to the Wisconsin

Association of Legal Administrators (WALA, www.wi-ala.org), which has

about 80 members statewide.

Typical responsibilities may include some or all of the following:

recruiting and supervising nonlegal personnel, participating in

orienting new associates, reviewing finances, preparing budgets and

financial plans, overseeing

physical facilities and equipment, evaluating and helping to select

technology, handling the firm's marketing, and planning and directing

office relocations.

Not only do job descriptions differ among firms, so do job titles.

Administrator and manager are the most common choices. Some view these

two positions as different; others use these titles interchangeably, as

happens with "paralegal" and "legal assistant."

Lori Kannenberg, firm administrator at Lawton & Cates, Madison,

and a former WALA president, says the distinction between an

administrator and a manager lies in the degree of responsibility. A

manager, for example, may attend to supervising staff, bookkeeping,

billing, and so on. An administrator may do that plus get more deeply

involved with all aspects of the business side of the practice,

including having input in setting the firm's strategic business

direction.

"The trend is for firms to empower administrators to make business

decisions," Kannenberg explains, "and to give them more autonomy in

making those decisions."

Salary Ranges

|

|

What do firms typically pay their administrators or managers? Below are

results from the Wisconsin Association of Legal Administrators' 2001

Compensation and Benefits Survey. The 2002 survey, to be published later

this month, will be available online at www.wi-ala.org.

|

|

|

Fewer than 15 attys

|

15 to 35 attys

|

36 attys or more

|

|

Job title: Firm administrator/business

manager

|

|

High wage

|

$62,000

|

$,000

|

$101,767

|

|

Low wage

|

$23,712

|

$47,000

|

$67,200

|

|

Average wage

|

$45,839

|

$69,790

|

$83,492

|

|

75th percentile

|

$55,250

|

$80,000

|

$92,942

|

|

50th percentile

|

$47,000

|

$68,266

|

$82,500

|

|

25th percentile

|

$40,500

|

$57,000

|

$73,050

|

|

Job title: Office manager

|

|

High wage

|

$50,128

|

$69,992

|

|

|

Low wage

|

$36,005

|

$43,992

|

|

|

Average wage

|

$42,890

|

$56,867

|

|

|

75th percentile

|

$46,322

|

$65,500

|

|

|

50th percentile

|

$43,472

|

$58,344

|

|

|

25th percentile

|

$39,645

|

$50,585

|

|

Firm size also enters into what administrators do. A large firm may

have managers for various departments, such as technology, human

resources, accounting, and marketing, and those managers in turn report

to an overall legal administrator. By contrast, a small firm may have a

part-time administrator who spends the remainder of his or her time

performing another function, such as paralegal or legal secretary

work.

Thus, the extent of autonomy and the exact duties vary by firm. "But

what I think is universal," Kannenberg says, "is that administrators

play the role of overseeing the day-to-day operations of the firm,

including supervising staff."

These days, firms of all sizes are bringing administrators on board.

Current WALA president Majewski notes that the fastest growing segment

of the organization's membership is administrators from smaller

firms.

"I think once your firm gets to be between seven and 10 lawyers, you

need to start thinking about having a full-time administrator," advises

Cindy Johnson of CareerTrac Professional Group, a Milwaukee law firm

placement company. But even smaller firms have taken this step. For

instance, Johnson is working with a four-attorney firm that's interested

in developing an administrator position.

Kohn, whose firm now has two partners and two associates, took on an

administrator when he was still a sole practitioner. He acknowledges

that his is a special case; his firm does a high volume of collections

work and has a support staff of 36 people. While still a solo, he had

six support staff, and he saw a need for an administrator even then.

Thus, it depends not only on firm size, but also the nature of the

practice - and, perhaps more than anything, on how willing the firm's

partners are to turn over administrative responsibilities.

"A lot of lawyers don't realize how much time they're wasting,"

Johnson points out, "and how valuable an administrator is. They still

think they have to do it all themselves."

Letting Go

With lawyers feeling increasing pressures at the office and finding

it harder to find time for their personal lives - as evidenced by

various Bar survey results - why does the "I'll do it myself" attitude

linger?

Part of it is the difficulty of letting go of management decisions.

In her 35 years of working with lawyers, "I have found that lawyers

don't like to relinquish responsibilities," Johnson says.

Lawyers, too, recognize this trait in their midst. "If you're going

to buy a copy machine," observes Green Bay attorney Greg Conway, "there

are people who will sit down and make a chart" to analyze the decision

in detail. "Meanwhile," he adds, "their (billable) hours are going to

hell."

Conway's 22-lawyer firm, Liebmann, Conway, Olejniczak & Jerry,

hired its first administrator about 15 years ago. As current managing

partner, Conway says it's important that he allow the firm's

administrator to do his job. "Scott (Heintz) knows how to do this

stuff," Conway notes, "and 99 percent of the time he's right. The other

1 percent, when I would have done something differently, I shut up. I

don't want to encourage constant reporting."

Another reason firms choose not to hire an administrator is because

they want to avoid adding another salary to the payroll, especially in

today's economic climate. Instead, the firms' partners opt to continue

handling administration themselves.

Johnson suggests another way to look at the affordability question.

"Keep track of your nonbillable hours," she suggests. "Calculate the

time you're spending on finances, marketing, personnel, and so on, and

multiply that by your billing rate." That exercise, she notes, may

transform a firm's outlook on whether hiring a legal administrator makes

economic sense.

Bear in mind, also, suggests Madison attorney Tom Solheim of Solheim

Billing & Grimmer, "You're paying for administrative services now,

one way or another. You may be paying for it in reduced ability to

produce revenues because you're taking all this time to keep the firm

running."

Or you may be paying in other ways. Attending to administrative

matters "may come out of billable time," Solheim points out, "but I

suspect it mostly comes out of time for leisure, family, exercise, and

hobbies."

What to Look For

A legal administrator should offer a blend of financial and human

resource management expertise, Johnson advises. Still, she says, lawyers

often downplay the human resources side. "Accounting is bottom line,"

she notes, "so it's easier to comprehend because it's dealing with

numbers. It's nonemotional."

But the human resource management aspect of a law practice, although

less concrete, is equally critical, Johnson emphasizes. First of all, it

means avoiding legal quagmires in dealing with employee terminations,

harassment claims, and discrimination complaints. Most importantly, it

can boost the ordinary daily functioning of the firm, Johnson

contends.

She cites the environment that human resources administrator Bob

Isacson has created at Milwaukee-based Reinhart Boerner Van Deuren. For

instance, monthly social functions mix everybody together, unlike the

usual scene where lawyers, legal secretaries, and paralegals each hang

out in separate enclaves. As a result of this and other efforts, "there

is a lot of camaraderie in that firm," Johnson observes. Turnover is

almost nil. And people who do leave usually end up eager to be hired

back. That kind of continuity benefits everybody in the firm.

Finding an administrator with a background in both finances and human

resources can be difficult, Johnson concedes. Usually, a candidate's

strengths will lie in one area more than the other. Some administrators

may need additional training to carry out all duties of the job. That's

why Johnson encourages new administrators to join WALA, which offers

training specifically focused on administration in law firms, as opposed

to other types of organizations.

Understanding the nature of law firms - or being able to absorb it on

the job - is another vital job qualification. Moreover, it helps if

administrators understand lawyers' particular idiosyncracies. "Lawyers

like to take charge," Solheim notes, "and it goes contrary to our nature

to delegate important matters to other people. It's helpful if the

manager knows that about lawyers and can help us learn how to

delegate."

That points to the multifaceted nature of the job, requiring more

than hard skills. "Sometimes you're a mediator," Solheim says,

"sometimes an affirmer, and sometimes a person who listens to troubles.

It involves a lot of tricky aspects."

Where to Look

Dianne Molvig operates Access

Information Service, a Madison research, writing, and editing service.

She is a frequent contributor to area publications.

Some firms hire a legal administrator from outside, while others look

within their ranks. In the latter, a legal secretary or paralegal

eventually becomes an administrator. Such was the case at Solheim

Billing & Grimmer in Madison. The three founding attorneys launched

the practice in 1994, and one year later, with two more attorneys on

staff, they saw a need for their secretary-turned-office manager to take

on additional administrative tasks.

"We were lucky that Monica (Hansen) could grow in the position,"

Solheim says, "and that she was willing to help out with clerical things

for the first year, when we didn't have enough management work for a

full-time manager."

Today the firm has nine attorneys, and Hansen's job likely will

continue to evolve as the firm's needs change, according to Solheim. For

instance, the firm may hire a bookkeeper to free up more of Hansen's

time for expanded administrative duties.

Before Liebmann, Conway, Olejniczak & Jerry hired an

administrator, the firm's partners divided up administrative duties,

"very inefficiently," Conway adds. "People at meetings would promise to

take care of something, then they'd get busy and wouldn't do it. It

became chaotic." At that stage, a couple of legal secretaries took on

certain administrative tasks. That, too, became unworkable. Growing

portions of time spent on administration meant the secretaries weren't

as available to the lawyers they worked for. When neither secretary

wanted to switch permanently to the administrator's job, the firm hired

from the outside.

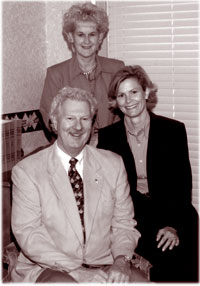

Dick Hemming, president of Consigny, Andrews,

Hemming & Grant in Janesville, prefers to train from within. When

Leanne Yaucher (seated) and Barbara Klukas evolved into the business

manager and the human resources administrator, others in the 12-lawyer

firm filled the vacated posts

Dick Hemming, president of Consigny, Andrews,

Hemming & Grant in Janesville, prefers to train from within. When

Leanne Yaucher (seated) and Barbara Klukas evolved into the business

manager and the human resources administrator, others in the 12-lawyer

firm filled the vacated posts

Hiring from within means the new administrator already is familiar

with the firm's culture and the individuals in the firm.

Counterbalancing that advantage are some special challenges. For one, a

staff member who has worked alongside coworkers may feel uneasy about

becoming their supervisor. And those former coworkers may harbor

resentments about the administrator's new role.

Another potential problem with in-house hiring is that the top

candidates for the administrator's job may be the very employees that

individual lawyers in the firm don't want to lose. They'd rather hang on

to those people as their secretaries or paralegals, even though it may

be in the firm's best interest that they become administrators.

Dick Hemming of Consigny, Andrews, Hemming & Grant in Janesville

offers a solution to that quandary: foresee the need and train from

within. At his firm, two support staff, Leanne Yaucher and Barbara

Klukas, have evolved into the business manager and the human resources

administrator, respectively. When they moved up, others in the firm were

ready to fill in the vacated posts, although Klukas continues as a

part-time paralegal.

To learn more ...

For a broader look at law firm administration in the context of firm

economics, please see The

Economics of Practicing Law: A 2001 Snapshot, by Dianne Molvig, in

the December 2001 Wisconsin Lawyer.

2001 Survey Report available. The Economics of Law

Practice in Wisconsin - 2001 Survey Report is available for purchase.

The special member price of $19.95 includes the report and any

additional analysis specific to your individual practice setting or

assistance needed in interpreting the information presented. Nonmembers

may purchase the report for $59.95. To order the report, or view the

report's introduction, go to report,

or contact the State Bar at (800) 728-7788.

Hemming says it's a constant process of bringing in and growing new

talent, and his firm starts early. "Of the last seven or eight

secretaries we've hired," he says, "I think five started with our firm

as co-op students right in high school." While in high school, the

students work part-time, but are treated as full-fledged staff members.

They know they're part of the firm and that jobs await them upon

graduation. Once they finish high school, they obtain two years'

additional training at area technical schools, while still working at

the law firm. As their skills grow, so do their on-the-job

responsibilities. By the time they become full-time employees, they've

already had three years' experience working in the firm.

"We've had so many of them come into the firm and impress us," notes

Hemming, who acts as the 12-lawyer firm's president. "So I think if for

some reason we had to replace Leanne or Barbara, I would hope I would

get some notice, and then I would certainly look within. If someone had

to give up a talented secretary, I'd get busy finding a qualified

replacement."

Is Now the Time?

Not every firm may need or want a legal administrator. But what are

some of the signals that it might be time to consider the possibility of

hiring one?

What Is Your Experience with Law Firm Administration?

The Wisconsin Lawyer editors would like to hear your thoughts about

this topic. Have you hired an administrator and what is the impact of

this decision? Or are you with a small firm that has figured out how to

succeed without an administrator? What advice do you have for others?

Please email your comments to the editors. We'll collect your

comments for publication.

Lagging behind in dealing with your accounts receivable may be one

indicator. High nonlegal staff turnover could be another. Perhaps your

staff isn't producing as it should be, or you're constantly cornered to

referee employee feuds. And you find it tougher to devote uninterrupted

chunks of time to practicing law.

These are just a few symptoms that indicate something is amiss. But

perhaps the most telling sign, Conway points out, is how you feel at the

end of the day. The time for hiring an administrator is ripe, he says,

"when you were in the office 12 hours and you only marked down six, and

you go home frustrated and discouraged."

Wisconsin

Lawyer