Cody Splitt, pictured here in her home in Appleton, is a World War II veteran and a Wisconsin lawyer. Photo: Shannon Green

On first impression, you might not realize that Cody Splitt is a centenarian.

The Appleton lawyer, seated in her home, gestures energetically as she speaks. She laughs often, her eyes and expression engaging. Her hair is brushed into an up-do, she wears big hoop earrings, and rocks a leopard-print blouse. She has no need of glasses and uses a walker to steady herself when on her feet.

And she has many, many stories to tell. Nearing 101 years old, Cody has seen a lot in her long life. Born just after World War I and the 1918 flu pandemic, her childhood included the Great Depression. She served in the Navy during World War II, and raised a daughter and opened then closed a law practice during the Cold War era. She practiced as a private attorney for 25 years before retiring in 1994. And in August 2019, she celebrated a century of living – seven months before the coronavirus pandemic hit Wisconsin in March 2020.

Born a Year Before Women Had the Vote

Cody’s mother, Anne Monahan Wendt, born in New York in the late 1800s, came to Wausau at the turn of the century as a secretary for an insurance company owner. “Back then, she was called a ‘typewriter,’” Cody said.

Shannon Green is communications writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. She can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6135.

Shannon Green is communications writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. She can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6135.

When Cody was born in August 1919, her mother – like all other women in the United States – was not allowed to vote. But that did not impede her from a passionate dedication to local politics. “She was one of the rare women to be so very active in politics.” Anne believed that every citizen should take an active part in preserving our system of government. “It’s fragile, and it needs people to participate in any possible way,” Cody said. “It was incredibly important to my mother, and that had a strong influence on my life.”

As a child, Cody helped her mother with the local campaigns. Cody’s political activities have now lessened, but she remained active in local politics throughout her life, including serving at one point as president of the Republican Women of Outagamie County and as vice president of the Outagamie County Republican Party. “I was a red-hot patriot. And I still am to this day,” she said.

Her mother’s dedication earned a visit to a sitting U.S. president, Calvin Coolidge. In 1927, Anne took 8-year-old Cody on a trip to Washington, D.C., where they met with Wisconsin Sen. Irvine Lenroot. Cody recalls that during the trip, Lenroot phoned her mother unexpectedly at their hotel, telling them, “The president would be happy to receive you.”

“Mom was so excited, she ran down to Wanamakers (Department Store) and bought me a little dress,” Cody remembers. “She was so excited she even forgot to powder her own nose.”

Cody has vivid memories of that trip to the White House. “We just walked straight in – so different from today. I remember (Coolidge’s) hand on my head. And he thanked my mother for what she’d done for the Republican Party in Wisconsin.”

‘Up and Down’: A Child in the Great Depression

During the Great Depression, Anne raised Cody by herself, earning a living as an accountant, her clients paying her with whatever they had. “This is what you did in the Depression,” Cody said. One client, a brewer, paid with beer. “My mother would exchange that for bread or whatever we needed. She also had a dairy client – which was marvelous, because we got eggs, milk, and cheese.”

Life in the Depression “was up and down. Some days we had pork chops, some days we had hamburger, and some days we had nothing at all,” Cody said.

Cash was hard to come by. “We didn’t even have a dime to go to the movie,” Cody said. Instead, her mother found a free source of entertainment for her inquisitive daughter – the courthouse in Wausau. Encouraged by her mother, school-age Cody regularly attended jury trials, where the lawyers arguing cases made a strong impression. “I thought they looked glamorous in their seersucker suits,” she said.

One day, after observing a jury trial, Cody told her mother, “I want to be a lawyer.” Her mother responded, “There is no reason in the world why you can’t be a spouse and a parent and a lawyer, just like a man can be.”

“She was ahead of her time,” Cody said of her mother.

Entering Adulthood: ‘Time to Earn a Living’

On graduating from high school, “I thought it’s time I earned a real living.” Traveling to Milwaukee, Cody got a job at a dress manufacturer. The factory “was a dumpy place,” but she wanted to work there because she loved the dresses. When Cody showed her mother the factory, she said, “Oh, buddy, you’ve got courage.”

Not long after, however, the factory went bankrupt, and the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 instigated the United States’ entry into World War II. When the U.S. Naval Reserve soon after opened a branch for women, Cody ended her work in Milwaukee.

Cody in her WAVE uniform during World War II. WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) served the Navy in non-combat roles.

For the Duration: Service in the WAVES

In July 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the law creating a women’s branch of service in the Navy, known as WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service). The women filled non-combat roles, from clerical positions to nurses, doctors, and flight instructors. Cody immediately signed up. “A lot of men I knew were in the war, in danger, and some had died. I thought, ‘I’ve got to do my share.’” Her mom was “all for it.”

On applying, Cody went to Chicago for a physical examination. “I met with Commander Black,” she said. “I can still see him to this day.” She was nervous. “I was so skinny I was afraid I wouldn’t get in – (being poor) I was used to not eating a lot.” The commander confirmed she was underweight for the Navy standards, but told her “I don’t think we’ll ever see you in the sick bay.”

The day she was approved to serve “changed my life,” Cody said. “I went from being poverty stricken to being in the Navy. Without the Navy, I wouldn’t be a lawyer.”

In January 1943, at age 23, she joined the women at boot camp in Cedar Falls, Iowa. “We were the first class of recruits,” Cody said. They studied Navy and U.S. history, engagement tactics, and the U.S. Constitution. In their new uniforms, they marched in formation in the snowy streets. “It was fabulous to be there,” she said.

The Navy men stationed there “were wonderful to us.” Cody remembers meeting one young man who was training to be an aviator. “We would go dancing,” she said.

At the end of boot camp, the women received their orders. Cody was assigned to Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. “That’s a nice base, but I was really hoping for Washington, D.C.” because of her interest in politics, she said. Learning that only trained secretaries were sent to Washington, D.C., Cody studied shorthand on her own, determined to pass the secretaries’ test. “I took it to bed with me, hiding it, and at lights out, did my damndest to make those marks.”

She tried her best to pass the test with her self-taught shorthand. “An officer looked down at what I scrawled and said, ‘Good God, no one could transcribe that. But if you want it that bad, we’ll send you to Washington, anyway.’”

D.C. in Wartime

In Washington, D.C., Cody joined women who worked on cracking Japanese-coded messages. The work was “extremely secret,” with the women taking oaths not to talk about it. “I even swabbed the decks on hot Washington nights, because we couldn’t have a civilian come in to where we were working on the codes,” Cody said. Even today she will not discuss the details of her work.

A few months later, Cody transferred to the Navy’s Bureau of Personnel, in charge of the morale of 200 WAVES. She arranged trips to the Smithsonian museums, the U.S. Supreme Court, and the U.S. Capitol. She used her connections with Wisconsin delegates to arrange a trip to the House of Representatives’ dining room. “I asked if it was okay to bring in 60 women,” Cody said. “They had wonderful bean soup,” she recalls. U.S. Rep. and Speaker of the House Samuel Rayburn visited with them. “He shook hands with every one of the girls.”

On Jan. 20, 1945, they stood in uniform to watch President Franklin D. Roosevelt take the oath of office for his fourth term. Cody will never forget seeing Roosevelt in a wheelchair, pushed by one of his sons. “They never showed that on television.”

They saw Roosevelt again March 1, 1945, when he addressed Congress on the Yalta Conference– where the three leaders of the Allies met to shape postwar peace. “I remember the president saying he never gave up anything at Yalta,” Cody said.

Witnessing history as it happened in Washington during the war “was breathtaking,” she said. “I got goose pimples from the time I arrived to the time I left. I told the girls to write down what they saw and did to tell their children someday.”

Cody spent three years in Washington, D.C. After the war ended in September 1945, her time as a WAVE ended, too.

After the War: Building a Career with the G.I. Bill

A Navy veteran, Cody resumed her education, returning to U.W.-Madison for both her undergraduate and law school degrees – working on both at the same time to make the most of her money from the G.I. Bill.

While a student, she resumed her support of Wisconsin Republican politics, passing out fliers on the Capitol Square and accompanying candidates as they traveled around Wisconsin giving campaign speeches. On a snowy day in 1946, Cody traveled from Wausau to Park Falls with Joseph McCarthy as he campaigned for the U.S. Senate. On that day, Cody and McCarthy were passengers in a car driven by the president of the Young Republicans. He drove the car “too fast in those snowy conditions,” in her opinion, but the speed “didn’t bother Joe at all.”

While they journeyed, Cody naively suggested to McCarthy, “If you don’t make it as a senator, you can still be a judge in Outagamie County.” After all, being a judge (McCarthy in 1939-42 served as a 10th District circuit court judge) “was a big thing” to Cody, at the time aspiring to become a lawyer. “I thought being a judge would be wonderful.”

But at her words, McCarthy turned to her and said, “My God, don’t you know the difference between a judge in Outagamie County and a United States senator?”

Cody laughs today at the memory. “He definitely was destined to become senator,” she said.

(Cody talks about her experiences with McCarthy in the Jan. 6, 2020, episode of “PBS American Experience on Joe McCarthy.” Her comments are available in the episode transcript, at pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/mccarthy/#transcript.)

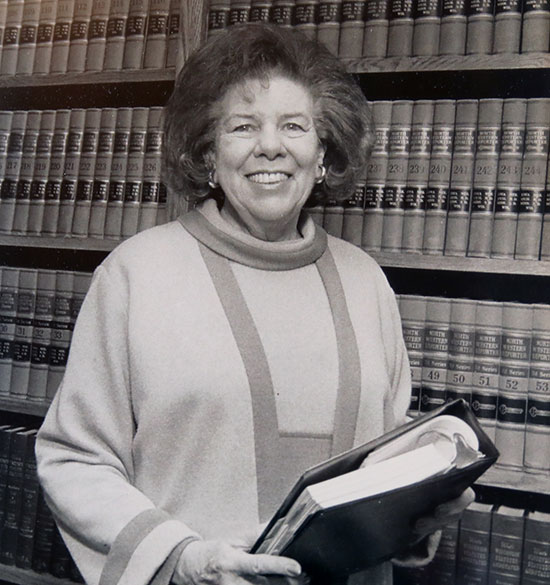

Cody Splitt, about age 60, pictured in her law firm in Appleton.

He Sat Next to Her – for 65 Years

Cody Wendt first met her future husband, Harley Splitt, in a restaurant in Madison in 1947. He sat behind her, and, each dining alone, they began to talk. She invited him to sit next to her. “And he sat down with me for the next 65 years,” Cody said.

They were married April 17, 1948, in the Wisconsin Supreme Court Hearing Room by a justice, the father of a law school classmate. Cody was 28, and Harley was 24.

An Army veteran of the Pacific theater in World War II, Harley earned a degree in business administration and became a CPA. They moved to Appleton after he accepted a position as a chief accountant for Fox River Tractor Co. in 1953. Their daughter, Leigh Rogers Splitt, was born in 1960. Harley passed away in 2012, at age 89. “I sure did have a wonderful life with him,” Cody said.

Opened and Closed: A Woman Lawyer in the Late 1940s

Thanks to the G.I. Bill, Cody fulfilled her childhood dream of becoming a lawyer. “My career really began with the Navy – without it, I wouldn’t have had the G.I. Bill, and I wouldn’t be a lawyer,” Cody said.

Cody was one of five women in her law school class. She graduated in 1949 at age 30, completing both her undergraduate degree and J.D. in just three years. “I never suffered any discrimination” as a woman in the law school, she said.

Once a lawyer, however, the situation changed. Cody watched with some jealousy as her male classmates got jobs in firms of varying sizes. “I didn’t get taken in by any firm,” she said. “They just weren’t ready to hire women.”

Cody watched with some jealousy as her male classmates got jobs in firms of varying sizes. “I didn’t get taken in by any firm,” she said. “They just weren’t ready to hire women.”

So she opened her own firm in Appleton in 1949. Her first customer was a man who needed a will. “He came in, took a look at me, said, ‘I thought you were a man,’” Cody said. “Then he turned and walked out.”

She managed to obtain a few clients – but it wasn’t enough. “I opened my practice and closed it almost right away,” she said.

The ‘50s and ‘60s: Volunteer Work, the Actress, and the Census

Career on hold, Cody concentrated on family and volunteer work. Her volunteer work “would fill a book,” she said. She continued her work in politics, gave speeches for a variety of organizations, and modeled for a Green Bay fur company’s advertisements. In 1960, she worked for the U.S. Census, managing the census in northeastern Wisconsin, supervising the door-to-door census takers. She performed in several plays with Attic Theater in Appleton in the mid-1960s, including performing the lead in The Desk Set in 1965. At a chance meeting at a train station, Wisconsin Gov. Warren Knowles invited her to work on the Civil Rights Commission.

In Practice – and the ‘Splitt Ticket’

In 1969, 20 years after closing her first law office, she tried again. By then, “people had gotten used to women professionals,” Cody said.

She operated a general practice, handling family law, estate planning, adoptions, wills, guardianships, divorces, leases, deeds, “all that kind of thing,” she said. “It was fun.”

Cody remained active in local politics, even running for Outagamie County judge in the 1970s, with the motto “Vote the Splitt Ticket.” She was the first woman to run for the position and made it through the primary. But she could not beat the popular Urban Van Susteren (father of Greta Van Susteren, a lawyer, legal analyst, and former television news anchor). “Everybody loved Van,” including herself, Cody said.

A Few Moments with Royalty

In 1971, Cody traveled to England with a group of American lawyers for a legal conference in London. A highlight was a tour of Buckingham Palace, which included a review by Princess Margaret outside on the lawn. “You weren’t supposed to talk to her,” Cody recalls. But veteran Cody recalled the royal family’s activities during World War II, especially those of then-Princess Elizabeth. “I loved that they stayed in London during the war,” said Cody.

Defying instructions, Cody spoke up as the princess walked by. “Princess Margaret, you have many friends in the United States,” she told her. “And we wish you well.” The princess responded, “Oh, how kind of you,” and they briefly chatted.

‘How Lucky Can You Get?’

After 25 years of practice, Cody closed her office on July 1, 1994, at age 74. “I thought it was time,” Cody said.

She did not stop her volunteer work. From 1994 to 2001, she served on the Outagamie County board of supervisors, and at age 66, in 1985, she became the first woman president of the Outagamie County Bar Association.

Would Cody recommend women become lawyers? “Of course. You can do a thousand things with a law degree – it’s invaluable. You can help so many people.”

When Cody celebrated a full century of living in August 2019, she gathered with a “few” friends – 100 or so – and rode in a limousine from her home to the Appleton Yacht Club, where the celebration was held. “It was such a marvelous time,” she said.

“Being 100 years old is wonderful. I thank the Lord for all I have and all I had. And all the friends I had through the years,” Cody said. “It’s so hard to believe! It doesn’t seem possible that you’d live to be 100. How lucky can you get?”