Vel Phillips was a trailblazer in law and politics in Wisconsin, breaking many barriers for women and African Americans. She was the first Black woman to graduate from the U.W. Law School.

Attending the Wisconsin Association of African-American Lawyers (WAAL) annual scholarship dinner in 2018 brought back many memories. A video tribute to Vel Phillips recognized her many accomplishments. I was involved in the very first scholarship dinner, named in honor of Vel’s late husband, W. Dale Phillips, who had recently passed away. He was one of Milwaukee’s unsung heroes who quietly made an impact on our community. Vel was thrilled with this recognition and gladly supported the idea and participated in the project. Dennis Archer, then a justice on the Michigan Supreme Court and later mayor of Detroit, was our first keynote speaker. He gave a rousing speech to a full house. The dinner celebration was a tremendous success.

Several of my colleagues were instrumental in making this happen. Deborah Ford, Michael Morgan, Sherman Mitchell, Vincent Lyles, James Hall, and Carl Ashley were in leadership positions in the Wisconsin Association of Minority Attorneys, formerly the Wisconsin Black Lawyers Association. All of them went on to do important work in the legal field. We all worked hard over the years striving to make contributions to the community.

In particular, I recall Felmers Cheney, a former Milwaukee police officer, who served as president of the Milwaukee chapter of the NAACP. The Milwaukee chapter received numerous requests for legal assistance and, because the organization did not have a legal staff, asked local lawyers to review cases. We had a revolving roster of attorneys who would volunteer on Saturday mornings and provide guidance to community members on potential civil rights violations.

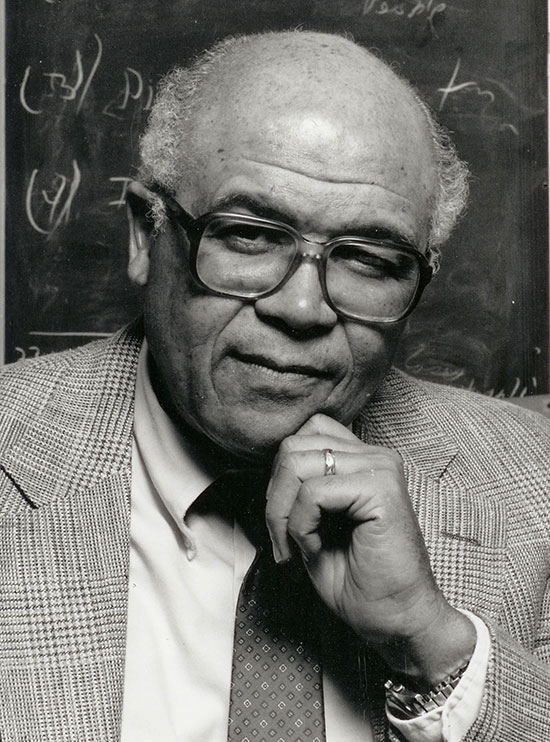

James Jones was the first Black law professor at the U.W. Law School. He was a labor scholar and a source of inspiration for many students with his unyielding persistence for excellence.

So Many Memories

I remember helping to organize mock trial tournaments for African-American high school students who did not have access to the State Bar of Wisconsin’s competition. Lawyers volunteered their time as coaches, role played as judges, and were fully engaged in the experience. Watching the young people rise to the occasion to appear and argue their cases, dressed in their Sunday best, was priceless. For me, these were defining moments filled with appreciation and joy, witnessing our young people full of self-confidence and tenacity in their court presentations. It was also fun for the lawyers, who loved the competition and the chance to contribute to the development of young people in our community. These were noteworthy moments that provided opportunities to give back, to promote dignity, and to experience Black pride.

Celia M. Jackson, U.W. 1980, has been in private practice and served as a Milwaukee County ADA, assistant dean at Marquette University Law School, and Secretary of the Department of Regulation and Licensing in the Gov. Doyle administration. She is currently retired.

Celia M. Jackson, U.W. 1980, has been in private practice and served as a Milwaukee County ADA, assistant dean at Marquette University Law School, and Secretary of the Department of Regulation and Licensing in the Gov. Doyle administration. She is currently retired.

I remember being actively involved in the State Bar of Wisconsin. I was one of the original members of the Minority Placement Committee. This was a group tasked with increasing the number of clerkship opportunities for attorneys of color in the major law firms. This group made a significant impact on Black attorney representation in corporate settings and preceded today’s Diversity Clerkship program.

I remember being sworn into the State Bar of Wisconsin along with some of my classmates, including Danae Davis, Fred Gordon, Paul Brady, Felix Mantilla, Yvonne Huggins, Beverly Njuguna, and Lelia Harmon. It was a proud moment after a journey laced with challenges and rewards. I later married Donald Jackson before joining the Milwaukee County District Attorney’s office, and he and Ken Cummings helped mentor me as a new trial attorney. I was the second African-American woman in that office.

When I worked at Marquette University Law School as an assistant dean, I witnessed several milestones. A group of seven Black students graduated in 1987. It was the first time in the history of the law school that more than two Black students completed the curriculum and graduated at one time. I also witnessed the first African-American woman professor in the law school, Phoebe Williams, who taught and had a long and distinguished career. She mentored many students during her tenure.

Mabel Raimey is believed to be the first Black woman to graduate from Marquette University Law School in 1927. Photo: Department of Special Collections and University archive - Marquette University Library.

Blazing Trails

I remember the courageous Black lawyers who came before me and helped to break barriers and pave the way for future Black attorneys. They include pioneers such as Lloyd Barbee and Vel Phillips; brothers Terrance Pitts, a county supervisor, and Orville Pitts, a noted lawyer in the Milwaukee City Attorney’s office; the Black-owned law firms of Roy Wilson, John Broadnax, and Clifton Owens; and the firm of W. Dale Phillips, Emmet Gambrell, LeRoy Jones, and Russell Stamper.

I remember the Black lawyers who were trailblazers in the large law firms: Richard Porter, John Daniels, Debra Lathen, James Hall, Walter White, Ulice Payne, Emile Banks, and others.

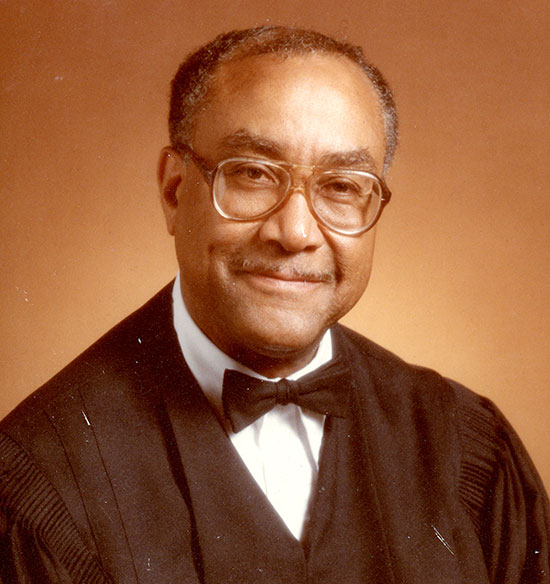

I remember the Black lawyers who went on to serve in a judicial capacity. They include family court commissioner Andrew Reneau and circuit court judges Vel Phillips, Clarence Parrish, Fred St. Clair, Harold Jackson, Russell Stamper, Stanley Miller, and Louis Butler. I was actively involved with a group working to increase the number of Black lawyers in the judiciary when Maxine White was appointed. She is now the Chief Judge in Milwaukee County. Judge Charles Clevert was the first African-American judge on the U.S. Bankruptcy Court and was later appointed as a federal judge, in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin. Paul Higgenbotham was the first and so far only African American to serve on the Wisconsin Court of Appeals.

I remember Louis Butler, who, as an attorney in the appellate division of the State Public Defender’s office, wanted more than anything to become a justice on the Wisconsin Supreme Court. He realized that dream and served for several years as the first African American in that capacity. That was an especially proud moment for many Black lawyers.

Clarence Parrish was an esteemed jurist and the first Black person to successfully win a contested election for Milwaukee Circuit Court judge.

Educating Generations

Jim Jones, a labor lawyer and professor at the U.W. Law School, vigorously encouraged us all to work hard and be successful. He made an incredible difference by being instrumental in the Legal Education Opportunities (LEO) Program, which was designed to address the persistent problem of underrepresentation of lawyers from historically disadvantaged groups. He was the architect of the Hastie fellow program, named after William Hastie, an African-American lawyer, educator, and advocate for civil rights.

The first Hastie fellows were Dan and Nancy Bernstine, from Washington, D.C., who provided support to students in the LEO program while working on their advanced legal degrees. Dan Bernstine later returned to lead the U.W. Law School as its first African-American dean. Winnie Taylor, the Hastie fellow when I started law school, was a welcome support and inspiration during that challenging first year. A host of other attorneys served with distinction in that capacity and were an invaluable resource to LEO program participants. Professor Jones’ contributions to the law school, the legal community, and Black lawyers were invaluable and will always be remembered.

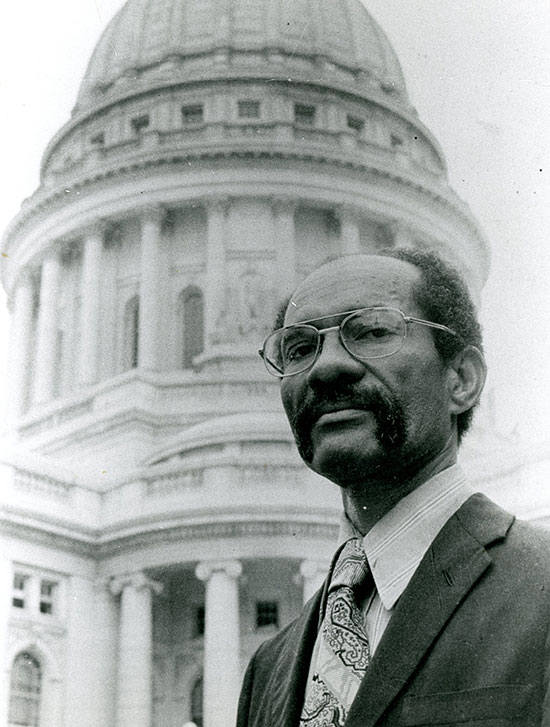

Lloyd Barbee was a tireless advocate in the Wisconsin Legislature and legal community, championing the issues of underrepresented people.

Challenging the Status Quo

I remember hearing the stories of attorneys who were actively engaged in civil rights and who challenged the status quo, among them Lloyd Barbee, James Dorsey, Vel Phillips, Theodore (Ted) Coggs, and Mabel Raimey. Attorney Raimey has the distinction of being the first African-American woman to graduate from Marquette Law School in 1927.

James Dorsey came to Wisconsin in 1928 and started a law practice. He was often referred to as the “Mayor of Bronzeville,” the Black section of Milwaukee. He built a strong political base and ran for alderman in the sixth ward in Milwaukee in 1936. Although he did not win the election, he was a force in the community and was instrumental in successfully addressing discrimination against Black workers in the five largest companies in Milwaukee during the 1940s.1

And I remember the Black women lawyers who were practicing when I graduated from law school: Vel Phillips, Mildred Harpole, Debra Lathen, Lela Davison, Sheila Parrish, and Joan Hicks. Our numbers have multiplied exponentially since then, and we now have successive Black women leaders in WAAL.

Daniel Bernstine was the first Hastie fellow in the U.W. Law School’s program designed to prepare underrepresented lawyers for teaching positions and support students in the Legal Education Opportunities Program. He later became the Dean and led the fundraising project to renovate the law school in 1996. Photo: Portland State University.

Conclusion

I have many memories about practicing in Wisconsin and the Black lawyers from whom I learned and those I have encouraged and helped over the years. We have an important history in this state.

WAAL is embarking on a task to identify all the Black lawyers who have practiced in Wisconsin or graduated from a Wisconsin law school. Some names have been lost. We are asking you to share with us the names of any Black lawyers you know that can be included in this count.2 We want to make sure everyone is noted.

And, for all of the Black lawyers that are able to come to the WAAL scholarship dinner in September, please put the date on your calendar when it is released. We are earmarking this year as a reunion. We are preparing a video and a booklet to commemorate this event.

As stated by my colleague, Roy Evans, reunions are important times that give people the opportunity to reunite our humanity and renew our spirits.3 It will be a wonderful celebration.

Meet Our Contributors

What is the best career advice you ever received?

The best advice that has served me in my career is based on lessons I have used in life provided by my mother. She told me a long time ago, “Stand up for yourself and regardless of your education and accomplishments, you are no more or less than anyone else.” This insight has instilled in me the balance of challenging the status quo and exercising compassion.

The best advice that has served me in my career is based on lessons I have used in life provided by my mother. She told me a long time ago, “Stand up for yourself and regardless of your education and accomplishments, you are no more or less than anyone else.” This insight has instilled in me the balance of challenging the status quo and exercising compassion.

One of the difficult lessons I have learned about the practice of law is that there is always a struggle between your head and your heart. It’s invaluable to know which one you are. I have learned that at my core I am a heart person. That has made all the difference in the world for who I am and how I nurture others.

Celia M. Jackson, Cudahy.

Become a contributor! Are you working on an interesting case? Have a practice tip to share? There are several ways to contribute to Wisconsin Lawyer. To discuss a topic idea, contact Managing Editor Karlé Lester at (800) 444-9404, ext. 6127, or email klester@wisbar.org. Check out our writing and submission guidelines.

Endnotes

1 Jack Dougherty, More Than One Struggle: The Evolution of Black School Reform in Milwaukee 33 (Chapel Hill, NC & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

2 Please send names to https://goo.gl/forms/tzMLYb3Pe1egk5Hd2.

3 Roy Evans, The Importance of Reunion, Wis. Law., Oct. 2018.