Wisconsin Lawyer

Wisconsin Lawyer

Vol. 84, No. 9, September 2011

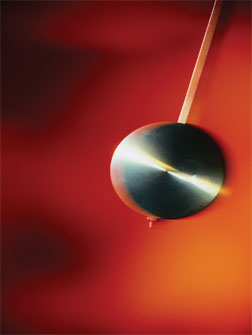

The pendulum of sentencing policy has swung back again in Wisconsin. Over the last 15 years, the state’s criminal sentencing laws have made the major transition from indeterminate to determinate sentencing, and then back to include some forms of early release from prison. Recently signed legislation, 2011 Wisconsin Act 38, which became effective Aug. 3, 2011, eliminates or adjusts many of the procedures that had allowed early release of certain inmates. This article looks at the history of Wisconsin’s sentencing laws, with particular focus on the early-release provisions of 2009 Act 28 and where each provision stands today after 2011 Wisconsin Act 38.

The pendulum of sentencing policy has swung back again in Wisconsin. Over the last 15 years, the state’s criminal sentencing laws have made the major transition from indeterminate to determinate sentencing, and then back to include some forms of early release from prison. Recently signed legislation, 2011 Wisconsin Act 38, which became effective Aug. 3, 2011, eliminates or adjusts many of the procedures that had allowed early release of certain inmates. This article looks at the history of Wisconsin’s sentencing laws, with particular focus on the early-release provisions of 2009 Act 28 and where each provision stands today after 2011 Wisconsin Act 38.

Sentencing Law Changes in Wisconsin at the Turn of the Century

Lawyers and judges who practiced criminal law in Wisconsin state courts before 2000 remember the previous, indeterminate system of sentencing under which incarcerated individuals did not serve their entire prison sentence but instead were eligible for parole after serving 25 percent of their confinement terms. These individuals typically were paroled at the discretion of the Parole Commission before their mandatory release date, the date on which two-thirds of the sentence had elapsed.

That indeterminate system was replaced by a determinate sentencing structure when truth-in-sentencing came to Wisconsin in two parts. The first part came in 1997 Act 283 for crimes committed on or after Dec. 31, 1999. Under Act 283, each offender whom a judge intended to imprison received a bifurcated sentence consisting of an initial prison confinement term of at least one year followed by a term of extended supervision (ES). The offender had to serve the entire initial term of confinement in prison, followed by the ES term. Violation of ES subjected the offender to return to prison for a period not longer than the ES term. In addition to setting the conditions of ES, when pronouncing sentence the judge considered whether the offender was eligible for the challenge incarceration program, sometimes known as “boot camp.” If an offender successfully completed boot camp, the remaining portion of the confinement term was converted to ES time, although the total length of the offender’s bifurcated sentence did not change.

While indeterminate sentences had allowed an offender “good time” credit, determinate sentences did not. Also, an offender could be assessed “bad time” in the form of extra days of confinement before release to ES. 1997 Act 283 also created the Criminal Penalties Study Committee, which was charged with developing the legislation to carry out truth-in-sentencing, including a new classification system for all felonies.

The second part of truth-in-sentencing came with the enactment of the work of the Criminal Penalties Study Committee in 2001 Act 109, which applied to offenses committed on or after Feb. 1, 2003. In addition to creating a new, uniform felony-classification system, Act 109 capped the maximum ES available at the time of sentencing and set up a process for the revocation of ES. Wisconsin courts possess the inherent authority to modify a previously imposed sentenced based on either new factors or a conclusion that the original sentence was “unduly harsh or unconscionable.”1 Act 109 did not alter an offender’s right to seek modification on these grounds.

Act 109 did, however, create additional procedures for modifying a bifurcated sentence. Either the Department of Corrections (DOC) or an offender could petition the sentencing court to modify any judicially imposed ES conditions. Also created was a statutory procedure for inmates to obtain early release from a term of confinement based on their age or a terminal health condition by petitioning the DOC program review committee.

As part of the legislative compromise to enact the work of the Criminal Penalties Study Committee, a mechanism was added at Wis. Stat. section 973.195 by which an offender could petition the sentencing court to adjust a sentence. Inmates convicted of certain crimes could petition the sentencing court to adjust their sentence after serving 75 percent of the offender’s confinement term (for Class F to Class I felonies) or after serving 85 percent of the offender’s confinement term (for Class C to Class E felonies). The section 973.195 petition for sentence adjustment had to be based on specific statutory grounds and was subject to the approval of the court, the district attorney, and the crime victim.

Also, in 2003 Wisconsin established a DOC-administered substance abuse treatment program known as the earned release program.2 An inmate serving the confinement portion of a bifurcated sentence who successfully completed the program had the remaining confinement period on the inmate’s sentence converted to ES.3 Statutory criteria dictated whether an inmate could be admitted to the earned release program, but the circuit court determined whether an offender was eligible to participate.4

2009 Act 28: Various Forms of Early Release

In 2009, Wisconsin adopted a series of early-release provisions that made changes to truth-in-sentencing. These changes, found in 2009 Act 28, became effective Oct. 1, 2009, and affected the determinacy of the offender’s original sentence. Rather than the sentencing court determining the confinement term, other entities, including the DOC and committees established by statute, could alter the length of an inmate’s confinement term or entire bifurcated sentence. These Act 28 changes included the following:

Positive Adjustment Time and Early Release. This provision allowed certain inmates to earn earlier release from prison by not violating any prison regulations and not refusing or neglecting to perform assigned duties.5 Individuals eligible for this “positive-adjustment time” were divided into certain categories, and how their sentence was adjusted depended on the category. Inmates serving such sentences could earn one day of positive-adjustment time for a certain number of days served. Broadly speaking, the more serious the felony, the more time the offender had to serve before accruing positive-adjustment time. If an inmate’s positive-adjustment time resulted in achieving early release, the release was to ES, the term of which was increased so that the total length of the bifurcated sentence did not change. An inmate who petitioned for positive-adjustment time could not apply for a section 973.195 adjustment of the same sentence for one year.6

Michael B. Brennan, Northwestern 1989, is a trial and appellate lawyer with Gass Weber Mullins LLC, Milwaukee. He served as the staff counsel for the Criminal Penalties Study Committee, which drafted the legislation that became 2001 Act 109. He served as a Milwaukee County circuit court judge for nine years.

Michael B. Brennan, Northwestern 1989, is a trial and appellate lawyer with Gass Weber Mullins LLC, Milwaukee. He served as the staff counsel for the Criminal Penalties Study Committee, which drafted the legislation that became 2001 Act 109. He served as a Milwaukee County circuit court judge for nine years.

Risk Reduction. Act 28 also created a program that allowed a court to order a person to serve a “risk reduction” sentence. If the offender successfully completed certain programming or treatment under this sentence, the offender’s bifurcated sentence could be reduced.7 For an inmate who received such a sentence, the DOC was to provide programming and treatment, assess the inmate’s risk of reoffending, and develop a plan designed to reduce such risk.

Certain Early Releases. Act 28 provided another new option for early release. The DOC secretary could release inmates to ES if 1) the inmate was imprisoned for committing a “non-violent Class F to I felony”; 2) the prison social worker or ES agent “had reason to believe the offender will be able to maintain himself while not confined without engaging in assaultive activity”; and 3) the release to ES was not more than 12 months before the ES eligibility date.8 This type of early release increased the ES term, and so the overall length of the bifurcated sentence did not change. Inmates who were serving sentences imposed before Oct. 1, 2009, could choose to apply either under this new early-release mechanism or under Wis. Stat. section 973.195.

Wis. Stat. Section 973.195. Act 28 limited sentence adjustments under Wis. Stat. section 973.195 to sentences imposed before Oct. 1, 2009. The mechanism of this statutory release remained essentially the same, except that the releasing authority was changed from the sentencing court to the Earned Release Review Commission.

Earned Release and Challenge Incarceration Programs. Act 28 expanded the earned release program from a substance abuse treatment program to a “rehabilitation” program and expanded the challenge incarceration program to include not just inmates with substance abuse treatment needs but also inmates with one or more treatment needs not related to substance use that were directly related to the particular inmate’s criminal behavior.

Earned Release Review Commission. Act 28 renamed the Parole Commission to the Earned Release Review Commission and expanded the commission’s duties. Previously, the Parole Commission had authority to grant discretionary release to inmates serving an indeterminate sentence. Act 28 added to that the authority to consider petitions to adjust sentences under positive-adjustment-time provisions for higher risk offenders, to adjust sentences under section 973.195, and to consider petitions for sentence adjustments by certain older or ill inmates.

Discharge from ES. Act 28 also authorized the DOC to discharge a person from ES after the person had served two years of ES if the person had met his or her ES conditions “and the reduction is in the interests of justice.” The DOC had to notify the offender’s victims, if any, of its intent to discharge the offender from ES. The DOC could promulgate rules establishing criteria and guidelines for the exercise of this discretion.

Discharge from Probation. Under Act 28, the DOC could modify an offender’s probation term and discharge the offender from probation if the offender had completed half of his or her probation term.

Release for Elderly Inmates and Inmates with Extraordinary Health Conditions. Under truth-in-sentencing, certain elderly and terminally ill inmates were allowed to petition for early release. Act 28 expanded that eligibility to certain inmates serving life sentences, and an inmate could request early release based on an extraordinary health condition, defined as advanced age, infirmity, or disability or a need for medical treatment or services not available within a correctional institution. To be eligible because of age, an inmate had to be at least 65 years old and have completed at least five years of confinement, or at least 60 years old and have completed at least 10 years of confinement.9 Act 28 also changed the releasing authority from the sentencing court to the Earned Release Review Commission.

Revocation of ES. Act 28 changed who decided how long offenders would be reincarcerated for violating their ES conditions. Before Act 28, the sentencing court (or its successor) would order the specific period of time, which was not to exceed the time remaining on the bifurcated sentence. Act 28 provided that if an offender’s ES was revoked, the reviewing authority – the Department of Administration’s Division of Hearings and Appeals (DHA) or the DOC – rather than the sentencing court made that decision.

2011 Act 38: Early Release Largely Ended

2011 Act 38, which became effective Aug. 3, 2011, eliminates or alters many of the Act 28 changes. The central consequence of Act 38 is that many of the early-release provisions of Act 28 either have been repealed or returned to their pre-Act 28 status. Tracking the categories described above, the changes include the following:

No Positive-Adjustment Credit. Under Act 38, offenders do not accrue positive-adjustment time. Certain inmates eligible for positive-adjustment credit for sentences served between the effective dates of 2009 Act 28 and 2011 Act 38 may be eligible for positive-adjustment-time credit, with that petition being made to the sentencing court.10

Risk-Reduction Sentences Eliminated. Act 38 repeals this sentencing option and release track. Offenders who received a risk-reduction sentence before Act 38’s effective date remain eligible for this release track, but that release decision will be under the authority of the sentencing court rather than the DOC.

Certain Early Releases. Act 38 repeals this sentencing option.

Wis. Stat. Section 973.195. Act 38 reinstates an offender’s ability to petition for sentence adjustment under Wis. Stat. section 973.195 after having served 75 percent of the confinement term (Class F to Class I felonies) or 85 percent of the confinement term (Class C to Class E felonies), and provides that an offender sentenced after Oct. 1, 2009, may file such a petition. It also returns that decision to the sentencing court from the Earned Release Review Commission.

Earned Release and Challenge Incarceration Programs. Act 38 repeals the expansions of these programs to general rehabilitation programs and focuses the programs on treating eligible inmates with substance-abuse problems. The earned release program is renamed the Wisconsin substance abuse program.11

Earned Release Review Commission. The authority of the commission, which had been expanded under Act 28 to consider petitions to adjust sentences under positive-adjustment-time provisions for higher-risk offenders, sentence adjustments under section 973.195, and provisions for certain older or ill inmates, is returned to its previous scope. The commission will again be known as the Parole Commission.

Discharge from ES. If the offender had met the conditions of ES, Act 28 authorized the DOC to discharge the offender from ES after serving two years of ES, provided that “the reduction is in the interests of justice.” Act 38 repeals this provision, so that each offender must serve his or her entire bifurcated sentence.

Discharge from Probation. The legislature considered repealing the Act 28 provision that allowed the DOC to modify an offender’s probation term and discharge the offender from probation if half the term had been completed. But ultimately the legislature amended the law to provide that on petition from the DOC, the sentencing court may modify a person’s probation period if certain statutory criteria are satisfied, including that the probationer has completed half the probation term, satisfied all conditions set by the sentencing court and the DOC, and fulfilled all financial obligations.12

Release for Elderly Inmates and Inmates with Extraordinary Health Conditions. Act 38 restored the pre-Act 28 law in this area, although the broader definition of extraordinary health condition, instead of the pre-Act 28 criteria of a “terminal illness,” has been kept. An offender may continue to petition for early release on this basis, although petitions will again go to the DOC Program Review Committee rather than the Earned Release Review Commission. Further, the sentencing court, rather than the Earned Release Review Commission, makes this sentence-modification decision.

Revocation of ES. When truth-in-sentencing was enacted, the decisionmaker as to whether or not an offender had violated ES remained the same: either an administrative law judge (ALJ) or the DOC. However, the determination as to the length of reconfinement for an offender violating ES was granted to the sentencing court. This was consonant with the philosophy of having the elected judge, rather than an unelected parole board or ALJ, making the confinement determination for an offender.

Act 28 returned that decision as to the term of reconfinement for violating an offender’s extended supervision to the DOC or an ALJ. Act 38 does not change current practice.

Expungement. Act 28 included some provisions for expungement of sentences. Act 38 does not alter those provisions.

Observations

The “return to the past” aspect of many of the 2011 Wisconsin Act 38 changes may make it easier to learn those changes than other sentencing law revisions.

At the center of the many changes truth-in-sentencing made to Wisconsin’s sentencing laws was the granting of authority to the sentencing court, rather than the Parole Commission, to determine the offender’s term of confinement.

Act 28 had distributed that determination among the DOC (positive-adjustment time, risk-reduction sentences, and certain early releases) and the Earned Release Review Commission (positive-adjustment time, sentence adjustment under section 973.195, and elderly inmates or extraordinary health conditions). The sentencing court (or its successor) played a much reduced role in any release decision.

Act 38 returns that decision to the sentencing court, although not for the determination of the confinement term for revocation of an offender’s ES.

In this most recent pendulum swing in Wisconsin’s sentencing laws, fewer sentence-adjustment and early-release provisions mean that when a sentence is pronounced more certainty will exist as to the amount of confinement time an offender will serve.

The tension between the policy behind truth-in-sentencing and providing a “mid-course correction” or “second look” at a sentence lawfully imposed is on display in Wisconsin’s sentencing laws enacted over the last 15 years.

Endnotes

1 See, e.g., State v. Grindemann, 2002 WI App 106, ¶ 21, 255 Wis. 2d 632, 648 N.W.2d 507.

2 2003 Wis. Act 33; Wis. Stat. § 302.05(3)(e). See generally State v. Johnson, 2007 WI App 41, ¶ 14, 299 Wis. 2d 785, 730 N.W.2d 661.

3 State v. Owens, 2006 WI App 75, ¶ 5, 291 Wis. 2d 229, 713 N.W.2d 187 (citation and footnote omitted).

4 See Wis. Stat. § 302.05; Johnson, 2007 WI App 41, ¶ 14, 299 Wis. 2d 785.

5 Wis. Stat. § 973.198.

6 Wis. Stat. § 973.198(6).

7 Wis. Stat. § 973.031.

8 Wis. Stat. § 302.113(9h)(a).

9 Wis. Stat. § 302.1135.

10 Wis. Stat. § 973.198.

11 Wis. Stat. § 302.05(1)(am).

12 Wis. Stat. § 973.09(3)(d)(1)-(6). A sex offender required to register under Wis. Stat. section 301.45 would not qualify for discharge from probation.

Wisconsin Lawyer