![]()

Vol. 71, No. 8,

August 1998

Following in the Family Footsteps

Devotion to the practice of law runs through

multiple generations of these Wisconsin families.

By Karen Bankston

Science has yet to identify an attorney gene, but a genetic predisposition

for the law seems to run through several Wisconsin families.

The hereditary link to the law is so strong that some families have not

one, but two or three attorneys in each generation. Some of these third,

fourth, even fifth generation attorneys have lawyer genes on several branches

of their family tree.

For example, the maternal grandfather of attorney siblings Virginia R.

and Daniel Finn was a Philadelphia lawyer, and their paternal grandmother

had three attorney brothers. Their father and mother, J. Jerome and C. Virginia

Finn, are both alumnae of Marquette University Law School, their father

"in the '50s (class of 1958)" and their mother "in

her 50s (class of 1989)," reports Virginia, an attorney with

Michael, Best & Friedrich LLP.

"If our family has any expectation of the law, it is that it will

keep your mind active. Our family values include the Irish love of a good

argument for argument's sake," she adds. "Perhaps we had to be

attorneys for that reason alone."

Thus, the flip side in the nature versus nurture debate wields some influence.

A nearly universal childhood experience among the sons and daughters of

attorneys was spending Saturday mornings at the law office, though few report

that those hours gave them clear insight into the practice of law.

"I really didn't have any concept of what he did at work,"

admits Joseph Tierney IV. "I guess I would have said, 'My father reads

books.'"

These families' professional heritage left vastly different impressions

on younger generations. Rebecca Wickhem Wegner's high school teachers collected

lawyer jokes she could take home to her father. John O'Melia Jr. remembers

attorneys from around the state descending on the family deer camp each

November. Whenever Thomas Drought's family traveled across the state, they

stopped for meals only at restaurants belonging to the association his father

represented. All in all, these must be good memories because the proud tradition

continues in these and other families across the state.

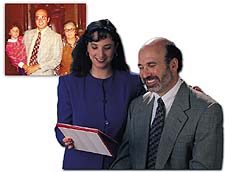

Legacy of Law: The Smolers

Harriet Stern Smoler, right, the 78th women admitted

to practice in Wisconsin, proudly appears before the Wisconsin Supreme Court

in 1975 to move her son, Bill's, admission to the bar. Bill holds daughter

Tedia, who was admitted to practice 23 years later. Below: Bill and Tedia

recently took a moment to admire Harriet's law school diploma, which now

graces Tedia's office.

|

Harriet Stern Smoler may not have practiced law for long, but her love for

the profession is reflected in the career choices of her son and three of

her 10 grandchildren.

The newest lawyer in the family, Tedia Smoler, stopped often on her way

to and from the U.W. Law Library to find her grandmother (Class of '29)

and father (Class of '75) in their class pictures. Harriet Smoler's law

school diploma hangs in Tedia's office at the Waukesha County Public Defender's

Office.

After Harriet Stern graduated from law school, she had her own practice

for a short time and worked with the Kenosha Social Services Department

early in the Depression, says her son Bill Smoler. After she married Fred

Smoler, Harriet switched careers to help operate the family retail business.

Bill believes his mother's passion for the law was manifest in the tradition

of gathering to watch "Meet the Press" and then adjourning for

a Sunday brunch that often stretched over one or two hours as the family

debated political issues of the day. "My mother led those discussions

in a way that was not dissimilar to what I experienced years later in law

school," he recalls.

Harriet appeared before the Wisconsin Supreme Court in 1975 to move her

son's admission to the Bar. "I believe that was one of her proudest

moments," says Bill, an attorney with Murphy & Desmond, Madison.

Harriet died in May 1997, a year before Bill's daughter graduated from their

alma mater. Harriet is one of Wisconsin's first 150 women lawyers who will

be honored by the State Bar at a reception in Madison in October. (Please

see the "President's Perspective" at page 5 for more information.)

Ask Tedia why she chose a law career, and she may say it comes down to

the difference between her scores on entrance exams for law school and the

psychology graduate school program.

"But my mother says she always knew I'd be a lawyer," Tedia

says ruefully. "She also always said that I like to argue, which I

used to think was a criticism."

Tied to History: The Droughts

The lawyers of the Drought family are linked with the history of Wisconsin's

highways, restaurants, and lumberyards.

James Drought was the executive director, secretary, and attorney for

the Milwaukee Automobile Club and played a major role in the development

of the state's automobile industry. In 1926 he joined his son, Ralph, just

out of the U.W. Law School, to form Drought & Drought. Father and son

practiced together until James retired in 1943. Ralph had a general practice,

and his two principal lobbying clients were the Wisconsin Restaurant Association

and Wisconsin Retail Lumbermen Association.

"I remember that whenever my family traveled around the state, we

could only eat in restaurants that were part of the restaurant association,

and we were always stopping to visit lumberyards," says Ralph's son,

Thomas.

Unlike his grandfather and father, Thomas never had an opportunity to

practice with his father, who died in 1957 while Thomas was still in law

school. Thomas practices with Cook & Franke, which started out as Drought

& Drought.

He sees many contrasts between the family law practice of his childhood

where photocopies hung from clothespins to dry and typewriters clacked away

in outer offices. "My grandfather and father had a true general practice,"

he notes. "Back then there was no such thing as environmental law,

telecommunications law, employment law. People didn't 'specialize' in aircraft

litigation or sports law."

Two of Thomas's children represent the fourth generation of Drought lawyers.

Kay Drought is director of the Legal Aid Society in Portsmouth, N.H. Her

sister Ellen was honored this spring as one of two fourth-generation graduates

from the U.W. Law School.

Ellen taught English in Japan, studied journalism, and considered pursuing

a Ph.D. in history before applying for law school. "Although I enjoyed

studying history, I wasn't passionate enough to pursue it," says Ellen,

who will join the securities team at Godfrey & Kahn, Milwaukee. "A

law degree is more versatile. In this day and age, lawyers do lots of different

things."

Triple Tradition: The Affeldts

The Affeldt Law Offices S.C., West Allis, includes three brothers, David,

Steven, and John, whose father, maternal uncle, and grandfathers on both

sides of the family were attorneys. It seems a foregone conclusion that

this third generation would take to the law. On the other hand, the three

partners are the youngest of seven children; their older siblings chose

other career paths.

"I don't think any of us felt as if we were pushed into law,"

John says, although the brothers agree that once they decided to become

attorneys, none of them considered any other path than joining the family

firm begun by their grandfather, George A. Affeldt, in 1909.

The Affeldt brothers have a general civil practice in the tradition of

their grandfather and father, George R. Their maternal grandfather, Louis

J. Fellenz, served as district attorney and circuit court judge in Fond

du Lac County and as a state senator. His son, Louis J. Fellenz Jr., also

was a state senator and later worked for the Federal Housing Authority.

Growing up in a big family was good preparation for practicing law together,

Steven says. "We learned early to get along and share because we had

to."

They remember childhood trips to their father's law office and orders

to be quiet whenever clients stopped by to consult George Affeldt in his

study at home. "We may not have understood totally what dad did as

a lawyer, but we always knew the amount of time, effort, and education required

to do the job well," Steven says.

Moses Hooper works at his desk in the Hooper Building

(now called the Algoma Building) at 110 Algoma Blvd. in Oshkosh. At one

time, Moses was the oldest practicing lawyer in the U.S. and the oldest

attorney to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court (at age 93). Edward F.

Hooper (seated at left) represents the family's fourth generation of lawyers.

He practices estate planning in Appleton. Kellett Koch (far right), representing

the fifth generation, recalls that his great-great-grand-father's career

was "a source of great pride in our family." |

Just as law has become a tradition in their family, engaging the services

of the Affeldt Law Offices is an institution for many families in their

hometown. "We have multiple generations of clients to go with our multiple

generations of lawyers," Steven notes. "We still work with some

clients who remember my grandfather coming to their house, and he's been

dead for 45 years."

Following Moses:The Hoopers

Moses Hooper attended Yale University Law School and then came to Wisconsin

in 1857. He settled first in Neenah and later in Oshkosh where his private

practice flourished. Moses was Kimberly-Clark's first corporate counsel,

a post he held until he retired in 1930 after 74 years in the law. At one

time, he was the oldest practicing lawyer in the United States and the oldest

attorney to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court (at age 93). He died in

1932 at age 97.

Moses was joined in his practice by sons Ben and Edward M., who succeeded

his father as Kimberly-Clark's corporate lawyer. William S. Hooper, Edward's

son and Moses' grandson, represents the third generation of Hooper attorneys.

The Hooper family didn't have a lawyer in the fourth generation until Edward

F. Hooper took an early retirement from his work as a senior systems engineer

with IBM to go to law school.

"I had to fill in for the fourth generation at the last moment.

It finally caught up with me," says the Appleton attorney who concentrates

in estate planning. "In fact, the fifth generation in our family was

admitted to the bar before the fourth."

Kellett Koch, the fifth-generation Hooper family attorney, recalls that

his great-great-grandfather's career was "a source of great pride in

our family." But it was his grandfather, a chemical engineer who chaired

the Kellett Commission to reorganize state government, who influenced Koch

to become an attorney. Koch practices with Koch & McCann in Milwaukee.

Trial's End: The Wickhems

On the eve of her law school finals, Rebecca Wegner recalls that her

proud father sent her a package filled with memorials full of accolades

for the first three generations of lawyers in her family.

"It terrified me," she confesses with a laugh. "I called

him up and said, 'What are you trying to do to me with all these tributes

for what my family has accomplished?'"

James G. Wickhem, the son of Irish immigrants, began his law practice

in Beloit in 1882, and his son, John D. Wickhem, was a U.W. law professor

who became a Wisconsin Supreme Court justice. The third generation was represented

by John C. Wickhem, a trial lawyer for almost 40 years, who served as president

of the State Bar. His wife, Mary, took a year of law school and served on

the Board of Bar Examiners and several State Bar committees. Mary's father,

John Boyle, was U.S. attorney for Wisconsin's western district, and her

brother, John J. Boyle, was a Janesville attorney who served as a Rock County

circuit judge.

James D. Wickhem practiced with his father as an associate, partner,

and finally as cocounsel until John's death in 1987. "My dad and I

were partners, and he used to kid that his legal education had been repealed

and recreated at least twice in his career," recalls James, a partner

with Meier, Wickhem, Southworth & Lyons, Janesville.

The fifth generation includes James Scot Wickhem, a patent law specialist

with Michael, Best & Friedrich LLP, Milwaukee, and Rebecca, who recently

began her law career at Foley & Lardner in Milwaukee.

Unlike Rebecca, who decided to pursue law early on (she cowrote a paper

on joint and several liability with her father in high school), Scot earned

a degree in chemistry and was considering his career options when his advisor

suggested patent law as a way to combine two interests.

Scot recalls that family vacations were planned around the court schedules

of his father and grandfather. His grandfather's succession of boats the

family used at their Canadian island getaway were all appropriately named

"Trial's End."

Is there a sixth generation of attorneys in the wings for the Wickhems?

Of his own children, Scot says wryly, "I'll try to steer them into

medicine, but who knows whether I'll succeed?"

Next Page

|