Times of turbulence and rapid social change often produce corresponding tension and debate within the courts. Such was the case during Wisconsin's Progressive era: Wisconsin Supreme Court Chief Justice John Winslow promoted to his colleagues and the public an ideal of "constructive conservatism" allowing flexibility of constitutional interpretation to meet modern conditions, while his colleague Roujet Marshall warned that such an ideal, if taken too far, would undermine the court's ability to preserve constitutional liberties and judicial consistency.1

The period from 1915 to 1940, following the Progressive era, is seldom thought of as a time of reform, but it produced many social and legal changes that equaled the major Progressive-era innovations in importance.2 It was natural that the Winslow-Marshall debate over the interplay between protection of individual rights and accommodation of social change would continue, and it did so through two new leaders: Marvin Rosenberry and Edward Fairchild.3

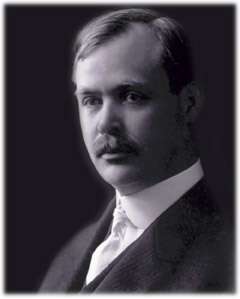

When Fairchild was a young man, his views were shaped by the then-prevailing free labor doctrine that emphasized the right of individuals to act for themselves free of governmental help or hindrance.4 But Fairchild also believed strongly in the imperative of serving the public and persons less fortunate than himself. He viewed such persons as "soldiers in the great war of commerce" who should be helped if, despite their best efforts, they came out as losers in that war. In a way, Fairchild viewed himself as a fellow soldier whose duty was to make sure they were given a fair chance in battle.5 This article examines the ways in which Fairchild's views shaped Wisconsin's legal history.

The Soldier's Preparation (1872-1930)

Fairchild was born into a middle-class family of modest means in 1872; he grew up in Pennsylvania and western New York. As a boy he came to believe in public service as a duty after hearing Civil War veterans talk about the sacrifices and risks they had undertaken in the war.6 Fairchild was not able to attend college, but his talent attracted the notice of a local attorney with whom he studied law. After being admitted to the bar at age 21, Fairchild concluded he would have a better chance of economic success if he moved west. In 1894 he moved to Milwaukee, which would remain his official residence for the rest of his life.

At first Fairchild practiced in a small firm with limited success. In 1900 he began his career in government when he secured appointment as an assistant district attorney. His new job brought him to public notice, and in 1906 he capitalized on his opportunity and won election to the state senate.7

Fairchild was a conservative by nature and, as a result, he eventually forged ties with business magnate Emanuel Philipp and other opponents of Gov. Robert LaFollette. However, Fairchild's differences with LaFollette's Progressives often were more stylistic than substantive. Fairchild and fellow Wisconsin conservatives recognized the need for reform in many areas and differed from the Progressives only as to the best means of achieving such reforms.8

Worker's compensation was a key case in point. By the end of the 19th century, employers as well as workers were coming to recognize that workplace accidents were an inevitable product of the industrial age, not simply a matter of worker carelessness, and that fault-based tort law was not well suited to rational allocation of the costs of such injuries. Workplace injury lawsuits created unacceptable risks for both employers and workers: a worker who was found even partly at fault would go uncompensated and face destitution, and employers who lost such suits could face ruinous expense. Thus in 1905, when the Wisconsin State Federation of Labor first proposed a worker's compensation system with a fixed scale of recovery regardless of fault, it received warm support from many conservatives.9 In an early speech supporting worker's compensation, Fairchild revealed the compassionate side of his conservatism and his strong sense of the duty of public service:

"One splendid trait of the American people has been its admiration of and loyalty to its soldiers. I am sure they are not less considerate of the men who are soldiers in the great war of commerce; men who bear the burdens of strife and who bravely meet the dangers incident to our industrial conditions. ... I do not imagine that the American people will ever endeavor to care for the shiftless and indifferent man, but the one who steadily and earnestly meets the responsibilities of life, who engages in his chosen occupation, has worked his way into the public consciousness to such an extent, that we find public opinion in favor of devising some method by which the loss ... shall be taken from him and those dependent upon him and placed upon the trade."10

In 1909 the legislature created an Industrial Insurance Committee to prepare a worker's compensation bill and appointed Fairchild a member. Fairchild and his colleagues wrestled with several delicate issues, such as whether the new system should be voluntary or compulsory, whether system costs should be paid by workers or employers, and the level of benefits to be given to injured workers.11 The committee eventually fashioned a compromise. The system would be voluntary, but employers and workers who chose not to participate would be subject to the risks of litigation. Workers would be required to opt in or opt out before they were injured, not after, but they would not be required to pay for the system, and Wisconsin created benefit levels that were more generous than those of other states.12

Fairchild and his colleagues did their work well. Their proposal was adopted by the legislature with only minor changes and soon after was upheld by the supreme court. Wisconsin's was the first comprehensive compensation system in the United States to pass constitutional muster.13

Fairchild left the state senate in 1910 to run for governor but was defeated by Francis McGovern, the Progressives' candidate. He briefly resumed the practice of law but in 1914 Fairchild's longtime ally Emanuel Philipp succeeded McGovern as governor and appointed Fairchild a circuit judge in Milwaukee. Fairchild remained on the trial bench until 1930 when another conservative governor, Walter Kohler, appointed him to the supreme court.14

Guardian of Individual Property Rights (1930-1940)

Fairchild joined the court shortly after Rosenberry had commenced his tenure as chief justice. Rosenberry's tenure (1929-1950) would turn out to be the longest of any chief justice in Wisconsin history. Rosenberry used his considerable personal charm and forcefulness to try to develop consensus on the court; in Fairchild's view, Rosenberry "aimed to make it impossible for control by any faction."15 Fairchild was equally strong-minded and did not hesitate to dissent when his views differed from those of his colleagues. In later life he recounted a 1936 incident when, disappointed by a proposed majority opinion, he challenged his colleagues by saying, "Very well, you file that opinion and I'll write a dissent that will make you look like monkeys." As the justices left the conference room a bystander mistakenly greeted another justice as "Justice Fairchild"; the justice then turned to the real Fairchild and said with some irritation, "Have you filed that opinion already?"16

After Fairchild's appointment, he and Rosenberry picked up the debate Winslow and Marshall had begun over the proper role of government in American society and the balance that the court should strike between individual rights and social needs.17 The debate became urgent as Wisconsin, along with the rest of the nation, entered the Great Depression in 1930 and calls arose for relief efforts and greater regulation by state government of the badly wounded private enterprise system.18

A series of challenges to laws the legislature enacted as part of Wisconsin's "Little New Deal" tested the policy of judicial deference to administrative government that Rosenberry had crafted in the late 1920s19 and also gave Fairchild his first opportunity to present a conservative critique of Rosenberry's policy. In 1931 the legislature passed a bank stabilization law to combat a wave of bank failures that swept the state at the beginning of the Depression. The law permitted banks to refuse depositors' demands for immediate payment and to refund their money over time if such a plan was approved by 80 percent of depositors.20 In Corstvet v. Bank of Deerfield (1936) the majority, speaking through Rosenberry, upheld the law against a due process challenge, reasoning that a temporary impairment of the rights of depositors who objected to deferred refunds was outweighed by the fact that their only other option was bank failure.21 Fairchild, however, dissented and served notice that he believed the court should defend individual property rights vigorously even (and perhaps particularly) in times of social distress. He cautioned that:

"Banks are important institutions and considerable factors in the scheme of our economy, but the rights of the creditors of these institutions are also matters of great concern. Although the creditor's debt may degenerate and become the subject of compromise in case of an insolvent bank, it cannot be ignored, much less so when dealing with a going institution."22

Fairchild expressed similar concerns in a series of cases challenging the 1933 Wisconsin Recovery Act (WRA), which gave the governor broad power to establish codes of fair competition for Wisconsin industries. The WRA was enacted in the hope that it would inhibit predatory competitive practices, which many Wisconsinites believed had caused the Depression.23 Even Rosenberry believed the WRA's delegation of power to the governor was too broad, and in 1935 the court struck down the law.24 But after the legislature amended the law by adding guidelines for the governor to follow, the court upheld the amended law in the Tavern Code Case (1936).25 Fairchild joined in the Tavern Code decision, but when other aspects of the WRA were challenged, he and Rosenberry resumed their debate.

In State ex rel. Attorney General v. Wisconsin Contractors (1936), the court upheld a WRA provision allowing the governor to assess regulation costs against each regulated industry. Fairchild dissented. He did not write an opinion, but he undoubtedly believed that privatizing the cost of enforcing a general law violated the regulated industries' due process and equal protection rights.26 The following year, in State ex rel. Attorney General v. Fasekas (1937), the court by a 4-3 vote upheld a WRA provision allowing the governor to impose minimum wage standards on regulated industries. Despite recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions that indicated such provisions were unconstitutional,27 the majority, again speaking through Rosenberry, concluded such power was reasonably related to regulation of unfair competition and was justified as an "emergency measure."28 Fairchild took strong exception: he argued that the federal Supreme Court's decisions must be followed and that the law's failure to give regulated industries the right to a hearing before wage standards were imposed was a fundamental violation of due process.29

The last major court debate over Wisconsin's "Little New Deal" came in the case of State ex rel. Wisconsin Development Authority v. Dammann (1938).30 Rural electrification was a top priority for New Dealers in both Washington and Madison. In 1937 the legislature enacted a controversial law appropriating money to the Wisconsin Development Authority (WDA), a private corporation created in anticipation of the new law to promote municipal utilities and electric cooperatives.31 In Dammann, a deeply divided court upheld the law. The court initially concluded the law delegated legislative power too broadly because it did not specify precisely how the WDA was to use its appropriation and did not provide for adequate supervision. But upon reconsideration, the court changed its mind: the new majority (which included Rosenberry) noted that the legislature had the right to amend the WDA's corporate charter at any time and concluded that that was sufficient control.32

In a vigorous dissent, Fairchild argued that the law far exceeded the bounds of permissible delegation of power: it was the first time the legislature had given regulatory power to a private corporation rather than an administrative agency subject to direct legislative control. Fairchild also was disturbed that the law made the government a market competitor of private power companies. "How is it possible," he asked, "to encourage the formation of power districts in general without throwing the weight of the taxpayers' money into the scales upon an election to determine a purely local and proprietary concern?"33 Fairchild was soon vindicated in the political if not the judicial arena. Late in 1938 the voters, concerned about the issues Fairchild had raised, elected a legislature considerably more conservative than its predecessor. The new legislature did not renew funding for the WDA, and after several years of struggle the corporation dissolved.34

Guardian of Individual Workers' Rights (1930-1940)

The debate between Rosenberry and Fairchild also played an important role in shaping modern Wisconsin labor law. The state's labor law system began to develop in the early 1880s.35 During the system's early years it was heavily influenced by the free labor doctrine, which viewed employers and workers as capable of negotiating fair labor contracts on their own without governmental intervention. Only gradually did it become clear to Wisconsin lawmakers that this view was largely a fiction and that unions were a legitimate means of redressing the imbalance of power between employers and workers.36 In 1931, a dramatic shift in favor of labor occurred: the legislature enacted a comprehensive code that for the first time actively sought to enhance labor's bargaining power. The new code explicitly declared that all workers had a right to organize, authorized a variety of union activities related to strikes and picketing, and expanded workers' right to a jury trial in cases involving labor disputes.37

Throughout the 1930s the court divided over the question of how broadly to interpret the rights granted by the 1931 code. Fairchild played a pivotal role in the court's decisions. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Fairchild did not view the interests of workers and unions as identical: he believed laws allowing workers to associate freely with each other and protecting their right to negotiate freely with employers were appropriate, but he was suspicious of laws that had the potential to favor unions at the expense of individual workers.38

The court's two leading labor decisions of the 1930s, American Furniture Co. v. Teamsters Local 200 (1936)39 and Senn v. Tile Layers Protective Union (1936),40 brought Fairchild's philosophy to the fore and highlighted the differences between Fairchild and Rosenberry as to labor issues. In American Furniture the court held by a 4-3 vote (with Rosenberry in the majority) that the 1931 code protected union picketing even in situations in which the targeted employer's workers opposed the union.41 Fairchild, joined by fellow conservatives Chester Fowler and George Nelson, criticized the majority for ignoring the importance of workers' right of free choice. He argued that government's role should simply be to create a level playing field between employers and unions competing for support of the employer's workers. In taking this position, Fairchild was not trying to favor employers or revert to pure free labor doctrine. He worried that if unions could act against workers' wishes, they might try to circumvent worker opposition by siding with employers and creating employer-dominated unions at the expense of workers' interests.42

In Senn, which was decided the same day as American Furniture, the court held that unions could strike for a closed shop (that is, a workplace where union membership is a condition of employment) even in a situation in which the employer worked alongside his employees.43 Fowler and Nelson dissented, denouncing the decision as "un-American, oppressive [to small business owners] and intolerable,"44 but this time Fairchild sided with Rosenberry. In his majority opinion, Fairchild explained that just as workers should have complete freedom to decide for or against a union, so a union should have complete freedom to compete with employers for workers' allegiance:

"If it be assumed that [the employer] cannot operate his business successfully upon the conditions now insisted upon by [the union], still no right of [the employer] now protected by law is invaded by [the union's] efforts. ... An economic contest has developed.... The nature of the controversy is one in which the court and law enforcing officers can have no interest other than to preserve the equality of each contender before the law."45

Once again, Fairchild's view ultimately prevailed in the political arena. The Progressive-dominated 1937 legislature enacted the Wisconsin Labor Relations Act (WLRA), which required employers to bargain in good faith with unions and went a step beyond federal law by allowing an employer to agree to a closed shop even when there was no evidence that the workers favored it.46 But the 1939 legislature repealed the WLRA and replaced it with the Wisconsin Employment Peace Act, which disallowed closed-shop agreements unless 75 percent of the affected workers supported such an agreement.47 The legislature agreed with Fairchild that the wishes of individual employees (subject to majority rule) should prevail over the interests of both employers and union leadership. Congress later incorporated Fairchild's view into the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, and it remains a basic component of labor law today.48

Later Years (1940-1965) and Legacy

With the onset of World War II, public attention turned to the war effort and turbulence over domestic issues subsided. The remainder of Fairchild's time on the court was more tranquil than his first decade. Fairchild succeeded Rosenberry as chief justice upon the latter's retirement in 1950. When Fairchild retired in 1957 he was succeeded on the court by his son Thomas Fairchild, who had gained prominence by playing a key role in the postwar creation of Wisconsin's modern Democratic Party and who was later appointed a federal appellate judge.49

Joseph A. Ranney, Yale 1978, is a trial lawyer with DeWitt Ross & Stevens S.C., Madison. He is the author of Trusting Nothing to Providence: A History of Wisconsin' Legal System (1999) and has taught as an adjunct professor at Marquette University Law School.

Joseph A. Ranney, Yale 1978, is a trial lawyer with DeWitt Ross & Stevens S.C., Madison. He is the author of Trusting Nothing to Providence: A History of Wisconsin' Legal System (1999) and has taught as an adjunct professor at Marquette University Law School.

Edward Fairchild died in 1965, having lived for nearly a century. That century witnessed many fundamental changes in legal and social thought, and Fairchild's judicial philosophy reflected many of those changes. As a young man Fairchild absorbed the free labor doctrine but tempered it with a sense of obligation to help those who had difficulty surviving in the marketplace despite their best efforts. Later, at the end of the Progressive era, Fairchild was flexible enough to accept the fact that government's role in American life had been permanently expanded and would be increasingly delegated to agencies, and that unions were now a permanent feature of the American economic landscape.

But Fairchild never relinquished his core belief that individual rights and individual freedom were paramount. During his tenure on the court, his was a consistent and sometimes lonely voice for protection of such rights against government encroachment even when his colleagues deemed such encroachment necessary to meet economic emergencies. His also was a voice for giving workers a fair chance to assert their interests against both employers and unions in the ongoing battle of industrial labor relations. Fairchild's views came to be accepted by many Wisconsinites and other Americans. His views played an important part in shaping Wisconsin's legal system as it exists today.

Endnotes

1 See Joseph A. Ranney, Chief Justice John Winslow: Stretching the Procrustean Bed, 76 Wis. Law. 22 (May 2003) [hereinafter Ranney, Winslow]; Joseph A. Ranney, Justice Roujet D. Marshall: The World of Buoyant Opportunism, 76 Wis. Law. 18 (July 2003).

2 See generally Joseph A. Ranney, Trusting Nothing to Providence: A History of Wisconsin's Legal System 377-422 (Madison, 1999).

3 See generally Ann Walsh Bradley, Marvin B. Rosenberry: Unparalleled Breadth of Service, 76 Wis. Law. 16 (Oct. 2003); Joseph A. Ranney, Shaping Debate, Shaping Society: Three Chief Justices and their Counterparts, 81 Marq. L. Rev. 923, 946-56 (1998).

4 For an overview of the free labor doctrine, see Joseph A. Ranney, Concepts of Freedom: The Life of Justice Byron Paine, 75 Wis. Law. 18, 21 (Nov. 2002); Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War 11-15, 261-62 (New York, 1970).

5 See Edward T. Fairchild, Fourth of July speech, 6 (untitled; no date, probably between 1909 and 1911), Fairchild Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society.

6 See id.

7 Index to Fairchild Papers, 1, Wisconsin Historical Society; In Memoriam: Chief Justice Edward T. Fairchild, 33 Wis. 2d xxix, xxx (1967).

8 See Robert S. Maxwell, Emanuel L. Philipp: Wisconsin Stalwart, 30-42, 58-71 (Madison, 1959).

9 See Robert Asher, The 1911 Workmen's Compensation Law: A Study in Conservative Labor Reform, 57 Wis. Mag. Hist. 123, 126-29 (Winter 1973-74).

10 Fairchild, supra note 5, at 6-7.

11 Asher, supra note 9, at 132-40; Ranney, supra note 2, at 348-52.

12 Asher, supra note 9, at 132-35; Ranney, supra note 2, at 348-50.

13 L. 1911, c. 50; Borgnis v. Falk Co., 147 Wis. 327, 133 N.W. 209 (1911).

14 Index to Fairchild Papers, supra note 7, at 1-2; In Memoriam, supra note 7, 33 Wis. 2d at xxxi.

15 Letter from Edward Fairchild to Robert B.L. Murphy, Sept. 7, 1961, in Fairchild Papers, supra note 5; see also In Memoriam: Chief Justice Marvin B. Rosenberry, 15 Wis. 2d xxix, xxxiv, xlii (1961).

16 Fairchild personal notes (emphasis in original), no date, in Fairchild Papers, supra note 5.

17 See Ranney, Winslow, supra note 1, 76 Wis. Law. at 25; Ranney, supra note 2, at 402-22.

18 See Paul E. Glad, The History of Wisconsin, Vol. V: War, a New Era, and Depression, 1914-1940, at 348-97, 448-82 (1990).

19 See Ranney, supra note 2, at 377-91; Bradley, supra note 3, at 18.

20 L. 1932-33 (Spec. Sess.), c. 15.

21 220 Wis. 209, 223-36, 263 N.W. 687 (1936).

22 Id. at 238-39 (Fairchild, J., dissenting).

23 L. 1933, cc. 64, 391, 476; see Ranney, supra note 3, at 950-51.

24 Gibson Auto Co. v. Finnegan, 217 Wis. 401, 412-13, 259 N.W. 420 (1935).

25 Petition of State ex rel. Attorney General, 220 Wis. 25, 264 N.W. 633 (1936).

26 222 Wis. 279, 268 N.W. 238 (1936).

27 Adkins v. Children's Hosp., 261 U.S. 525 (1923); Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo, 298 U.S. 587 (1936).

28 223 Wis. 356, 364-65, 269 N.W. 700 (1937).

29 Id. at 366-75 (Fairchild, J., dissenting).

30 228 Wis. 147, 277 N.W. 278 (1938).

31 L. 1937, c. 334.

32 228 Wis. at 166, 171-202.

33 Id. at 219 (Fairchild, J., dissenting).

34 Glad, supra note 18, at 516-17.

35 Robert Ozanne, The Labor Movement in Wisconsin: A History (1984), passim; Ranney, supra note 2, at 392-98.

36 Ranney, supra note 2, at 392-404.

37 L. 1931, c. 376.

38 Ranney, supra note 3, at 954-55.

39 222 Wis. 338, 268 N.W. 250 (1936).

40 222 Wis. 383, 268 N.W. 270 (1936), aff'd, 301 U.S. 468 (1937).

41 Id. at 347-71.

42 Id. at 372.

43 Id. at 387-91.

44 Id. at 396 (Fowler, J., dissenting).

45 Id. at 389-90.

46 L. 1937, c. 51.

47 L. 1939, c. 57.

48 61 Stats. 136 (1947); see also Ranney, supra note 2, at 956.

49 Fairchild Memorial, supra note 7, 33 Wis. 2d at xxx; Index to Fairchild Papers, supra note 5, at 2. As to Thomas Fairchild, see William F. Thompson, The History of Wisconsin, Vol. VI: Continuity and Change, 1940-1965, at 567-71, 588-94 (1988).