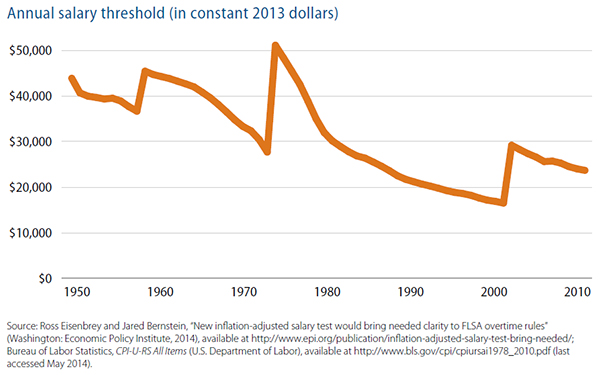

The minimum wage is once again a hot-button issue, as many people advocate for a nationwide increase. Others question how a higher minimum wage would affect job creation and corporate profits. With all the focus on the hourly minimum wage, little attention has been paid to America’s “salaried minimum wage” – the minimum an employer can pay salaried “white-collar” employees, such as executives and professionals, to avoid overtime requirements. Currently, the salaried minimum wage is $455 per week or $23,660 annually, an income just below the poverty guideline for a family of four.1 If the salaried minimum wage were adjusted to its 1975 level, accounting for inflation, it would be $984 per week or $51,168 annually.2 (See Figure 1.)

The minimum wage is once again a hot-button issue, as many people advocate for a nationwide increase. Others question how a higher minimum wage would affect job creation and corporate profits. With all the focus on the hourly minimum wage, little attention has been paid to America’s “salaried minimum wage” – the minimum an employer can pay salaried “white-collar” employees, such as executives and professionals, to avoid overtime requirements. Currently, the salaried minimum wage is $455 per week or $23,660 annually, an income just below the poverty guideline for a family of four.1 If the salaried minimum wage were adjusted to its 1975 level, accounting for inflation, it would be $984 per week or $51,168 annually.2 (See Figure 1.)

President Obama and many other Americans argue that the current regulations governing overtime-exempt salaried employees are obsolete, confusing, and inconsistent with the intent of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). One of the main issues they cite is the outdated salary threshold of $455 per week. As a result of this low weekly amount, only 11 percent of salaried workers currently qualify to earn overtime, compared to 65 percent in 1975.3 Moreover, courts have interpreted the exemptions broadly, finding many low-paid employees to be exempt from receiving overtime pay.

The regulations and case law governing the executive exemption from overtime illustrate President Obama’s concerns well. For instance, Burger King assistant managers are overtime-exempt executives as a matter of law, despite the fact that they spend most of each day performing nonexempt work such as cashiering, cleaning, and food preparation. If these employees are paid at or near the $455 weekly salary threshold and work more than 40 hours per week, they could potentially earn a lower hourly wage than their subordinates.4 In response to this perceived distortion of the FLSA’s overtime exemptions, President Obama has authorized the Secretary of Labor to update and modernize the country’s overtime regulations.5

This article examines the current regulations governing the FLSA’s white-collar exemptions from overtime, focusing specifically on the executive exemption. It then considers recent decisions interpreting the executive exemption, both nationwide and in the Seventh Circuit. Finally, it discusses likely updates to the regulations and their effect on workers.

Figure 1

The Salary Threshold Has Fallen Dramatically Since 1975

Executive Exemption Exemplifies President Obama’s Concerns Regarding the Current Regulations

The FLSA, 29 U.S.C. §§ 201-219, provides exemptions from both minimum-wage and overtime requirements for bona fide executive, administrative, professional, and computer employees. These exemptions are commonly known as the white-collar exemptions. The FLSA does not define “executive, administrative, professional, or computer employee”; instead, it expressly delegates that task to the Secretary of Labor, who may periodically alter the definitions.6

Breanne L. Snapp, U.W. 2013 cum laude, Order of the Coif, is with the Madison office of Habush Habush & Rottier S.C., where her practice includes wage and hour class actions. She is a member of the 2014 Wisconsin Pro Bono Honor Society, and serves on the Board of the Legal Association for Women.

Breanne L. Snapp, U.W. 2013 cum laude, Order of the Coif, is with the Madison office of Habush Habush & Rottier S.C., where her practice includes wage and hour class actions. She is a member of the 2014 Wisconsin Pro Bono Honor Society, and serves on the Board of the Legal Association for Women.

To qualify as an exempt employee, an individual must be compensated on a salary basis at a rate of not less than $455 per week or $23,660 annually.7 In addition to the compensation requirements, all exempt white-collar employees must meet a “duties test.”8 (Please see the accompanying sidebar for the other duties tests.)

Current Regulations Governing the Executive Exemption’s Duties Test Result in Confusion and Inconsistent Decisions. To qualify for the executive exemption, an employee’s primary duty must be managing the business.9 The exempt executive must regularly direct the work of at least two full-time employees and have some authority or input in hiring and firing employees.10

The regulations provide the following examples of management activities:

- Interviewing, selecting, and training employees;

- Setting and adjusting employees’ rates of pay and hours of work;

- Assessing employees’ productivity and efficiency;

- Handling employee complaints and disciplining employees;

- Determining the types of materials, supplies, and equipment to be used;

- Determining the types of merchandise to be bought, stocked, and sold;

- Planning and controlling the budget; and

- Monitoring or implementing legal-compliance measures.11

In the retail and food-service industries, many managers and assistant managers spend the majority of their time performing the same nonexempt work done by hourly employees. Therefore, litigation surrounding the executive exemption typically hinges on whether the employee’s primary duty is the performance of exempt managerial work.

The term primary duty means the principal, main, major, or most important duty that the employee performs.12 Courts consider the following factors when determining the primary duty:

- The relative importance of the exempt duties as compared with other duties;

- The amount of time spent performing exempt work;

- The employee’s relative freedom from direct supervision; and

- The relationship between the employee’s salary and the wages paid to other employees for the kind of nonexempt work performed by the employee.13

Proponents of changing the regulations cite two major concerns with the current duties test. First, for their primary duty to be the performance of exempt work, managers need not spend more than 50 percent of their time performing exempt work.14 Counterintuitively, managers can spend the majority of their time performing the same nonexempt duties as their hourly subordinates and still be exempt from overtime.

Duties Tests for the Administrative, Professional, and Computer Employee Exemptions

Duties tests for the other white-collar exemptions to the overtime requirements are summarized below.

Administrative Exemption. To qualify for the administrative exemption, an employee’s primary duty must be the performance of office work directly related to the management or general business operations of the employer or the employer’s customers, and the employee must assist with running or servicing the business.36 The employee’s primary duty must include the exercise of discretion and independent judgment with respect to matters of significance to the company.37 The regulations provide examples of work “directly related to management or general business operations,” including tax, accounting, insurance, advertising, human resources, and legal and regulatory compliance.38

Professional Exemption. To qualify for the learned-professional exemption, an employee’s primary duty must be the performance of work requiring advanced knowledge in a field of science or learning, typically acquired through a college or similar program of instruction. Common examples of exempt learned professionals include doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, and engineers. The creative-professional exemption applies to employees whose work requires invention, imagination, originality, or talent in a recognized field of artistic or creative endeavor. Many musicians, actors, authors, and painters meet the requirements for the creative-professional exemption.39

Computer Employee Exemption. Exempt computer employees include computer systems analysts, computer programmers, software engineers, and other similarly skilled workers in the information technology field. The computer employee exemption applies only to computer employees whose primary duty consists of:

The application of systems analysis techniques and procedures, including consulting with users, to determine hardware, software, or system functional specifications;

The design, development, documentation, analysis, creation, testing or modification of computer systems or programs, including prototypes, based on and related to user or system design specifications; or

The design, documentation, testing, creation or modification of computer programs related to machine operating systems.40

Courts have struggled to reconcile the language of the computer employee exemption with the ever-evolving technology industry. While it is clear that information technology support specialists are nonexempt,41 the exempt status of certain employees in the software industry has not been resolved. For example, end-user testers of software or employees who simply configure software generally have little to no education or technical training in the computer sciences. Nevertheless, many employers classify such individuals as exempt.

Second, the regulations explicitly provide that exempt managers can concurrently perform both exempt and nonexempt work. For example, an employee is able to serve customers at a drive through or stock shelves in a store while also supervising and directing the work of his or her subordinates.15 This framework arguably destroys the divide between exempt and nonexempt work because, theoretically, any solitary task could be considered a duty concurrent with management.

Because the FLSA is a remedial statute, the U.S. Supreme Court has directed that its exemptions are to be narrowly construed against employers and are “limited to those establishments plainly and unmistakably within their terms and spirit.”16 In practice, however, courts have interpreted the exemptions broadly, particularly the executive exemption.

From the early 1980s through the mid 2000s, federal circuit courts unanimously found restaurant and retail store managers exempt from overtime pay.17 In fact, the Government Accountability Office commented in 1999 on the difficulty of challenging exempt classifications for employees who supervise at least two employees, even if they spend only minimal time on management tasks.18

Prompting this movement was the seminal case Donovan v. Burger King (Burger King I),in which the First Circuit rejected the Secretary of Labor’s finding that Burger King misclassified its assistant managers as exempt executives. Although the employees spent the majority of their time performing nonexempt work, the court focused on managers’ concurrent performance of exempt and nonexempt work and held that they were exempt executives.19 Other circuit courts soon followed the First Circuit’s lead and thereby solidified the exempt status of low-paid restaurant and retail store managers throughout the country.20

Although there have been successful challenges to managers’ exempt status in the past 10 years,21 today’s legal landscape confirms the difficulty that management employees face in challenging their exempt status. In 2011, for example, the Fourth Circuit’s In re Family Dollar Litigation decision took the regulation’s allowance of concurrent duties to its extreme in holding that Family Dollar’s managers were in fact exempt executives.22 In that case, the lead plaintiff claimed to have spent 99 percent of her time performing nonexempt duties, such as stocking freight, running a cash register, and completing janitorial work.23 Nevertheless, the court held that she was “performing management duties whenever she was in the store, even though she also devoted most of her time to doing the mundane physical activities necessary for its successful operation.”24

Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals and Wisconsin Federal Court Decisions are Limited to Individual Claims

There have been no class actions challenging the exempt status of managers in either the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals or Wisconsin’s district courts. However, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals and the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin have decided individual employees’ challenges to exempt executive classifications.

In 2003, the Seventh Circuit affirmed a decision of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois that a car wash manager was a nonexempt employee entitled to overtime. In Jackson v. Go-Tane, the plaintiff spent 95 percent of his time performing the same duties done by the business’s regular car wash attendants.25 He frequently swept the premises, washed windows, and guided cars through the wash tunnel. The plaintiff’s salary amounted to $6.66 per hour, compared to the regular car wash attendants’ rate of pay – $6 per hour. Furthermore, the plaintiff’s discretion was limited, and he had to clear all decisions related to hiring, firing, and raises with the defendant business’s general manager. The court found that, in reality, the plaintiff operated as a “glorified car wash attendant.”26

Wisconsin’s federal courts have decided only one challenge to an executive exemption classification since the Seventh Circuit’s Go-Tane decision. In 2004, the Western District of Wisconsin court granted summary judgment to a U.W.-Whitewater food-service operator, holding that the university dining hall’s executive chef was an exempt manager.27 In Scherer v. Compass Group USA Inc., the plaintiff’s primary duty was to oversee food production for regular and catered meals. He prepared menus, supervised and trained at least five hourly staff members, determined the amount and manner of all food production, ordered all food and tracked inventory, and ensured compliance with sanitation standards.

Although the plaintiff spent approximately 75 percent of his time cooking, the court, citing Burger King I, emphasized that the plaintiff was able to monitor the kitchen staff while he was preparing food.28 In addition, the court reasoned that the relative importance of the plaintiff’s managerial duties versus food preparation was confirmed by his salary, which was nearly twice that of the hourly kitchen employees.29

Updating the Regulations Could Potentially Restore the Intent of the FLSA and Benefit Many Wisconsin Workers

The FLSA and the regulations implementing it are predicated on the industrial economy of the mid-20th century, when the lines between managers and subordinates were clearer. In light of the modern service-oriented economy, President Obama has asked the Department of Labor to update and simplify the regulations to address the changing nature of the workplace.30 The proposed rule was originally expected to be issued in November 2014 but has not yet been released.31 Still, it is possible that the new regulations could go into effect before the end of President Obama’s second term.

Many observers have speculated regarding the content of the proposed changes, but most predict that the salary threshold will be increased substantially, from $455 per week to as high as $984 per week.32 The most modest proposal, and the one rumored to be under consideration at the Department of Labor, is $807 per week or $42,000 annually.

In addition to an increased salary threshold, new regulations will likely implement a strict 50 percent limitation on nonexempt work such as cashiering, preparing food, and cleaning.33 Employees who spend more than 50 percent of their time on these nonexempt duties would not qualify for an exemption. Proponents of this change in the duties test argue that it would lend much needed clarity to employers, and exclude from the exemptions employees who are not bona fide white-collar workers.

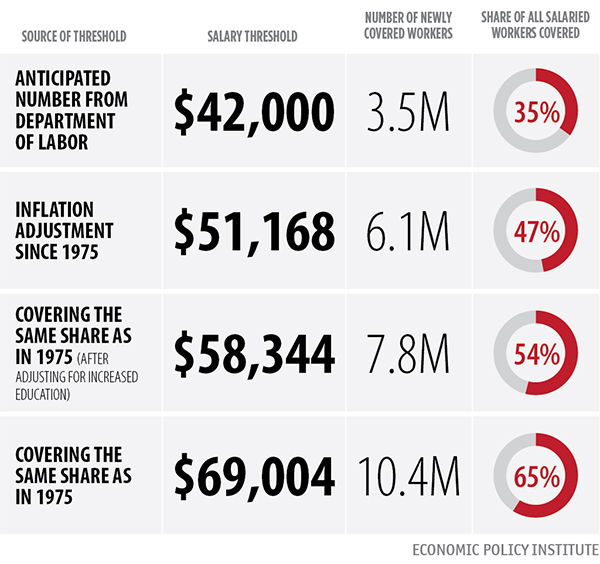

The overall effect of the new regulations on Wisconsin workers and businesses is unknown, but many salaried workers would be newly eligible to earn overtime pay based on the increased salary threshold alone. (See Figure 2.) Currently, only 8.9 percent of Wisconsin’s salaried employees qualify for overtime. If the salary threshold were adjusted to its 1975 level, accounting for inflation ($984.00 per week or $51,168 per year), 44.3 percent of Wisconsin’s salaried employees would be eligible to earn overtime.34 At a time when many Wisconsin families are struggling just to get by,35 the ability to earn overtime wages could give employees a needed boost in take-home pay.

Critics argue that businesses will suffer under the new regulations, causing them to freeze hiring or reduce hours. On the other hand, proponents contend that increased overtime wages would boost consumer spending and tax revenues and reduce unemployment by spreading jobs among more workers.

Figure 2

How the Proposed Overtime Thresholds Affect Workers

Endnotes

1 See 2015 Poverty Guidelines, U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs. (Jan. 22, 2015).

2 See Ross Eisenbrey, Economic Snapshot: Where Should the Overtime Salary Threshold Be Set? A Comparison of Four Proposals to Increase Overtime Coverage, Economic Policy Institute, Dec. 23, 2014.

3 Id.

4 At $455 per week, an employee working 40, 50, or 60 hours earns $11.38, $9.10, or $7.58 per hour, respectively.

5 See Memorandum For the Secretary of Labor, The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, March 13, 2014 [hereinafter White House Memo].

6 See 29 U.S.C.§ 213(a)(1), (17).

7 See 29 C.F.R.§ 541.100(a)(1), 29 C.F.R. § 541.200(a)(1), 29 C.F.R. § 541.300(a)(1), 29 C.F.R. § 541.400(b).

8 See 29 C.F.R. § 541.0(b).

9 See 29 C.F.R.§ 541.100(a)(2).

10 See 29 C.F.R.§ 541.100(a)(3), (4).

11 See 29 C.F.R.§ 541.102.

12 Id.

13 Id.

14 See 29 C.F.R.§ 541.700(b): “…Time alone, however, is not the sole test, and nothing in this section requires that exempt employees spend more than 50 percent of their time performing exempt work….”

15 See 29 C.F.R.§ 541.106(a), (b).

16 See Arnold v. Ben Kanowsky Inc., 361 U.S. 388, 392 (1960).

17 See, e.g., Donovan v. Burger King Corp., 672 F.2d 221 (1st Cir. 1982); Thomas v. Speedway SuperAmerica LLC, 506 F.3d 496 (6th Cir. 2007).

18 See U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO/HEHS-99-164, Fair Labor Standards Act: White-Collar Exemptions in the Modern Workplace 4 (1999).

19 See Donovan,672 F.2d at 226.

20 See, e.g., Donovan v. Burger King Corp., 675 F.2d 516 (2nd Cir. 1982); Murray v. Stuckey’s Inc., 939 F.2d 614 (8th Cir. 1991); Jones v. Virginia Oil Co., 69 Fed. Appx. 633 (4th Cir. 2003); Thomas, 506 F.3d 496.

21 In 2008, the Eleventh Circuit upheld a $36 million jury verdict against Family Dollar for misclassifying its store managers as exempt executives. See Morgan v. Family Dollar Stores Inc.,551 F.3d 1233 (11th Cir. 2008).

22 See In re Family Dollar FLSA Litig., 637 F.3d 508(4th Cir. 2011).

23 Id. at 520.

24 Id. at 517.

25 Jackson v. Go-Tane Servs. Inc., 56 Fed. Appx. 267, 268 (7th Cir. 2003).

26 Id. at 269, 271.

27 Scherer v. Compass Group USA Inc., 340 F. Supp. 2d 942 (W.D. Wis. 2004).

28 Id. at 945-46, 952-53.

29 Id. at 953.

30 See White House Memo, supra note 5.

31 See Department of Labor Semiannual Regulatory Agenda, Spring 2014.

32 See New Inflation-Adjusted Salary Test Would Bring Needed Clarity to FLSA Overtime Rules, Economic Policy Institute, March 13, 2014.

33 See Eisenbrey, supra note 2.

34 See Ross Eisenbrey & Will Kimball, Economic Policy Institute Economic Snapshot, Jan. 15, 2015 (citing Analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group (ORG) Microdata).

35 According to the Pew Charitable Trust’s March 19, 2015 report, Wisconsin ranks worst among the 50 states in terms of a shrinking middle class, with real median household incomes falling 14.7 percent since 2000, and the percentage of Wisconsin families belonging to the middle class dropping from 54.6 percent to 48.9 percent. See Stateline Analysis of American Community Survey, U.S. Census and Integrated Public Use Microdata Series – USA, University of Minnesota.

36 See 29 C.F.R.§ 541.200(a)(2), 29 C.F.R. § 541.201.

37 See 29 C.F.R. § 541.200(3).

38 See 29 C.F.R. § 541.201(b).

39 See 29 C.F.R. § 541.300(a)(2), 29 C.F.R. § 541.301(c), 29 C.F.R. § 541.302(a), (c).

40 See 29 C.F.R. § 541.400(a), (b).

41 See Department of Labor Opinion Letter, FLSA 2006-42, Oct. 26, 2006.